Chronicle: Community and peasant feminisms of Abya Yala met for the third time in Tilcara

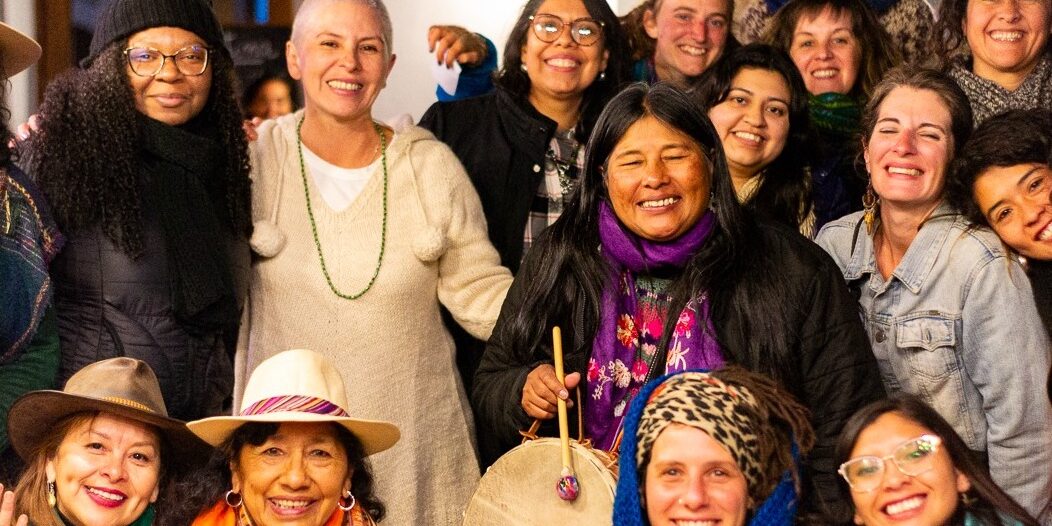

For three days in Tilcara, women and diverse community feminisms from Latin America gathered to exchange experiences and knowledge about politics, spirituality, and epistemology.

Share

Spirituality, politics, and feminist epistemologies. This triad was the central theme of the Third International Gathering of Community, Peasant, and Popular Feminisms in Abya Yala , which took place from August 16th to 18th in Tilcara (Jujuy). It is one of several regional gatherings of women and diverse groups held in Argentina, but this one brings together, in a leading role, people of diverse cultural and sexual identities, as well as racialized identities, from the strategic periphery. In the Quebrada de Humahuaca (a UNESCO World Heritage Site), a meeting point of ancestral cultures, this territory serves as a gateway to the Altiplano and other Andean regions, and its beauty defies description.

It was organized by the Rodolfo Kusch Institute (National University of Jujuy) together with Casa Mama Quilla and the Quilla Network. Adriana González Burgos , its coordinator, can now say, “We have triumphed.” “Self-management, one of the forms and manifestations of a popular feminist economy, has allowed us once again to hold this gathering. Against all negative predictions, we achieved a different kind of communal feminist management and politics, sustained by reciprocity, without a single peso of funding, in the political context of hunger, right-wing policies, the advance of neoliberalism and financial capitalism. For us, this is a success.” She points to it as one of the great achievements, but not the only one.

The guests

Among the special guests invited this year were women with renowned careers and diverse expertise: Esther Pineda, academic and activist for Black feminisms; Moira Millán, Mapuche weychafe (warrior); the amauta (healer) sisters Wara and Rosa; and Silvia Federici, philosopher and one of the leading activists in anti-capitalist feminisms. She was ultimately unable to travel due to her partner's health.

“When we are downcast, it is the earth’s forces that revitalize and heal us,” Moira Millán reminded us in her talk on spirituality, the Mapuche people, and territory. “There is no greater love than that of the Earth. When things are done right, the earth responds.” And in a way, during these three days, the Earth responded and embraced this Gathering at a difficult and complex political moment for feminisms and diverse movements, where these initiatives offer respite, momentum, and reflect great agency.

“Self-management is economic, political, spiritual, and epistemic autonomy. But we live in this territory, in this country,” says Adriana. There were fewer people than last year in Tilcara. Anticipating this, the Gathering was also held virtually, with streamed talks and the option to participate in virtual workshops, in addition to the in-person ones. Activists from Nigeria, Panama, and Brazil joined the virtual activities, analyzing the role of women in Yoruba, Ifa, and Orisa spirituality in Abya Yala.

“In 2025, our goal is for Africa to be here in Tilcara. Holding the gathering here is one of our banners of resistance. We are usually invited to relocate. Or we have been invited to take the gathering to other places. And we have maintained it once again in this little piece of land, the land of our grandmothers and ancestors. We are convinced: the political, spiritual, and economic alternative will come from the peripheries,” says Adriana.

What was coming, what came

Last year at this gathering, I met Betiana Colhuan, a Mapuche spiritual leader (machi) , who had just spent eight months imprisoned along with other Mapuche women and had resisted a violent eviction operation in defense of the Lof Winkul Mapu community near Bariloche. I also met Natalia Machaca, an Indigenous defender criminalized by the government of Gerardo Morales for participating in the Third Malón de la Paz (Peace March) resistance in Jujuy.

The machi Betiana arrived with her young son and her mother, María Nahuel, and during the Pachamama ceremony, she embraced Natalia. The machi was also a constant presence in Purmamarca, continuing the fight against Morales's reforms. Some warned that Jujuy was a kind of laboratory or testing ground for what might come in terms of reforms and repression.

If Indigenous communities already felt threatened at that time, many things changed in 2024 after Javier Milei became president. During his campaign, Milei had already declared himself an enemy of women and LGBTQ+ people. And as president, he set about dismantling the Ministry of Women, Gender and Diversity, gender policies, and institutions like INADI, and promoting a series of reforms that leave historically vulnerable groups unprotected.

The attacks on Indigenous communities were reinforced by the Ministry of Security, with Patricia Bullrich equating drug trafficking with the defense of territorial rights. But they also came from the executive and legislative branches, which approved the Framework Law and, within it, the Large Investment Incentive Regime (RIGI), which jeopardizes the right to a healthy environment and opens the commercialization of common resources to transnational capital.

Weaving community

In this context, the Encounter invited us to share tools to strengthen ourselves and to think about how to build politics from feminist perspectives. This plurality, a hallmark and core strength of this encounter, is reflected in the tone of the presentations and workshops, which seek horizontality and exchange within a space that is also one of rupture.

“ The Gathering was also necessary as a demonstration of the strength of other forms of organization that don't depend on funding, but rather operate through community networks from a pluralistic perspective in this current situation, ” Adriana says, reflecting on the event. “Institutions, organizations, movements, communities, and individuals all participated, making their contributions. So, when we say we are anti-capitalist, anti-colonialist, anti-patriarchal, and anti-racist, we are also acknowledging our current political climate. And that alliances can be forged, community can be built, even with those who don't think like us but are also convinced of the need to build a more just community and world.”

Arriving from afar

“Knowledge is collective, communal. If it’s only for each individual, it’s useless. It has to be for everyone,” said Adriana González Burgos at the opening of the lecture series. The Encounter had actually begun the day before with this exchange of knowledge and activities designed “to welcome the sisters who are arriving.” Because another defining characteristic of this gathering is its unique pace.

On that first day of presentations, the participants shared experiences of community care, artivism, feminist economics and poetry, interculturality, and struggles, such as that of the Mapuche women vegetable growers in Chile, which Sheila brought to the table. I met Sheila when we got off the plane together. "Spanish?" I asked. "Galician!" she corrected me. Sheila lives in Temuco, Chile; she is a lawyer, professor, and researcher in criminal and criminological matters from a feminist legal perspective. She took three planes and several buses to get to the Encuentro. Also from the south came Romina Villafañe, a history professor, who led the workshop on Genocide and Resistance of the Mapuche Nation, after traveling 2,800 kilometers from her home in Esquel, Chubut. Moira Millán also came from that province, from the Lof Pillán Mahuiza community.

Moira and Esther Pineda - who arrived from Venezuela - poet, sociologist, Master of Science in Women's Studies, postdoctoral fellow in Social Sciences - together with Silvia Federici, are part of the Diploma in Community, Peasant and Popular Feminisms in Abya Yala that is developed with the National University of Jujuy.

“ Building friendship in the process is part of creating another form of feminism, not from the struggle for spaces but from believing in each other's projects and supporting them . That's how we've been supporting each other. Esther has been supporting Mama Quilla from day one, and also the Diploma in Community Feminisms (Unju),” Adriana highlighted when introducing Esther's conference.

Feminist epistemologies and ruptures

“Epistemology has traditionally been a space dominated by patriarchy. The way we think about how and why we do things has been conceived by men and for their monopoly,” Pineda stated. “When we talk about a feminist epistemology, we are talking about new ways of relating to and building upon each other, not from the hegemonic patriarchal logic, but from how we think about the world from our perspective as women . This is to transform what affects us, but also for all our sisters, daughters, and friends.”

Pineda proposes a break with “hegemonic feminism of Enlightenment origin.” She refers to the kind that assumes we should only be concerned with violence against women, and that other forms of oppression and discrimination are not the concern of feminism. She criticizes this “hegemonic feminism” for “its inability to question the intersection of violence and discrimination that affect us as Black women.”

However, she cautioned that this hasn't led her to stop identifying as a feminist, but rather has motivated her to explore other ways of practicing feminism, alongside racialized women and women from marginalized communities in Latin America. “What's happening in the US and Europe isn't speaking to us. That's why I choose to live and think as a Black woman, a school of thought that has made significant contributions to feminism,” Esther said in her lecture.

Do not give up on feminism

“It is essential that we reclaim this category and imbue it with new meanings and ways of practicing feminism,” she emphasized. “Part of creating new feminisms is to make inequalities like racism visible, and to address domination from an intersectional perspective in order to raise awareness.”

Returning to the ideas she presents in her books, she explained, “The master’s tools are not going to bring down the master’s house. But sometimes we have to use them, to enter those spaces that have been denied to women and racialized identities.”

Pineda recalled that the idea that we are inherently inferior has forged a quintessential privileged subject: the white, heterosexual, and resourceful man. “Taking over the spaces they have held is a way of transgressing and transforming the logic of domination in our lives and communities,” she said. All women, regardless of age, education, or class, “have at some point experienced forms of sexist and racist violence. Some of it is physical, sexual, psychological, economic, or institutional. And this affects our quality of life.”

On beauty and aesthetic violence

“My goal has been to build tools so that people can understand and explain certain concepts. Femicidal cultures, Afro-femicide, aesthetic violence. These are concepts that allow us to explain realities that we need to name.” And to close her talk, she read a series of poems, including this one from * Cuando me rompo escribo poesía* (Sudestada).

We will never be

beautiful.

We will never

meet

your expectations

or demands.

We are always

too fat,

too Black,

too ugly,

too old.

We will never be

enough.

We will never

fulfill

your ideals:

unrealistic,

unattainable,

alien,

distant.

Aesthetic violence, she explained, is based on four forms of discrimination: racism, sexism, ageism, and fatphobia . Esther said that part of her fight against aesthetic violence involves choosing not to wear makeup.

Later, Moira Millán returned to the topic. “Growing old is the worst thing that can happen to you in Huincaland. In our Mapuche community, being an elder is an honor; you have to act and speak with wisdom and prudence. For Huincas, beauty is an economic matter, based on products to perpetuate youth. In our worldview, beautifying the life of the land is what defines you. What we have to do is wrest control of our identity from the patriarchy,” she proposed.

The importance of the territory

“I cannot speak as a Mapuche woman without expressing my solidarity with Palestine,” the weychafe . Her talk focused on explaining the connection between spirituality and territory, and the relationship between territory and politics.

“ Spirituality is celebrated where there are forces of nature that form the circle of life. We need the land to practice spirituality. It can’t be done in the street or in a temple; we need sacred sites, which are in the hands of transnational corporations, mining companies, Benetton, and large landowners,” said Moira. “Where they see a beautiful landscape, they want to appropriate it, build their hotel and their mansion. That vitality and that greenery exist because there are spiritual forces sustaining life. The sacred spaces of the Mapuche people are those territories.”

Moira explained that the machi Betiana's rewe (sacred space) is under military occupation. Days ago, the Federal Court of Cassation revoked the agreement signed between the national government and the Mapuche community. She shared that the new administration of National Parks is in constant conflict with the Mapuche people, citing the case of Lof Paillako and its response to a court-ordered eviction.

“ The so-called Mapuche conflict will not be resolved through the laws of the white man. It will be rebuilt with love, respect, and listening, and that cannot happen under the conditions in which we live today. If there is one thing all governments have in common, it is their subjugation of nature and exploitation of our land.”

How can spirituality be recovered?

Moira doesn't speak of feminism, but of patriarchy. And of the need to strengthen spirituality as a tool. “In the Mapuche world, there are no mental disorders, only spiritual imbalances. This civilizational matrix is one of death. Epistemicide is part of terricide. We need to use other kinds of tools that they don't have. To recover spirituality. When we restore cosmic order, life begins to be reestablished.”

In their ceremonies, the Mapuche people speak directly to the power of the earth. “When we speak, there is a response. Sometimes the animals guide us, or the wind blows in our favor. The earth speaks to us; we are not alone . Spirituality is not folklore or improvisation; that is cultural appropriation. How do we recover spirituality? By listening to the people in their territories,” Moira explained .

“The European bourgeoisie often expects me to be a shaman or a machi. They took away our life and spirituality, but some want us to have kept the secrets so that oppressed European society can revitalize itself, and they want us to give it to them in exchange for nothing. They don't want me to tell them how their capital comes to pollute. They're going to have to listen,” she said, and the audience applauded loudly.

“"The struggle to preserve the spirituality of our peoples is intrinsically linked to our territory and is a political struggle," he explained, demonstrating how politics and spirituality are intertwined.

Regarding new ways of building politics, she cited the example of the trawn , a space for listening and debate among the Mapuche people. “ I like to think of my people’s democracy in a horizontal way. The trawn is sacred, the space where we listen to each other. Building a new way of doing politics involves remembering how we celebrate life.”

What patriarchy could not

The event included more talks, a space in the plaza for a feminist fair and exchange, tributes, and awards. Among those honored were Argentina Paredes, a 76-year-old pastor, folk singer, and healer; Marimar, a trans activist with Damas de Hierro and adoptive mother of three; and Rebeca Camacho, Josefina Aragón, and Erminda Mamaní.

Adriana González Burgos' interview with the Wara and Flor Rosa sisters, amautas (ancestral healers) from Suriqui Island, on Lake Titicaca (Bolivia), yielded some definitions about what spirituality is in a broad sense.

“You are all Pachamama to me,” they greeted the audience in Aymara at the Tilcara Municipal Hall. “ Spirituality is the tool that patriarchy and capitalism have not been able to take from us,” González Burgos began her talk. She then announced a project with the Bolivian sisters: the creation of a traditional medicine school to teach children to remember their roots and develop their consciousness.

“Andean spirituality is about understanding how you relate to Pachamama, how you give thanks. What kind of relationship you have. How much you have expressed gratitude. Being at peace with yourself, that is the way to relate to Pachamama ,” the sisters explained.

The energy is within.

Holding the Gathering in August, a busy month for Andean communities, is part of their identity. On Sunday, Wara and Rosa Flor participated in the offering ceremony to Pachamama. This marked the closing of the Gathering, which began at midday and continued until sunset, with participants sharing offerings, food, and songs.

Music was a crucial element. At the lively gathering on the first night, Cristina Paredes, a musician, singer, and teacher from Tilcara, shared her diverse verses, a strategy for combating hatred. Yanet Alarcón and Kurvf Ailen brought the music of northern Neuquén, while Dani García, Elsa Tapia, and Las Venus del Monte had everyone dancing in the courtyard of Capec (Andean Center for Education and Culture).

Micaela Chauque coordinated a workshop on traditional folk songs at the Pucará de Tilcara, a high-altitude botanical garden. Beneath her hat, with her drum in hand, Micaela recounted to the group of participants how she learned to sing by listening to her grandmother, a shepherdess, as she walked up and down the hills. “She taught me that the energy is inside, in the heart. I learned it over time ,” she explained after asking permission of the earth and before playing with the songs. It was her idea to hold the workshop at the Pucará.

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.