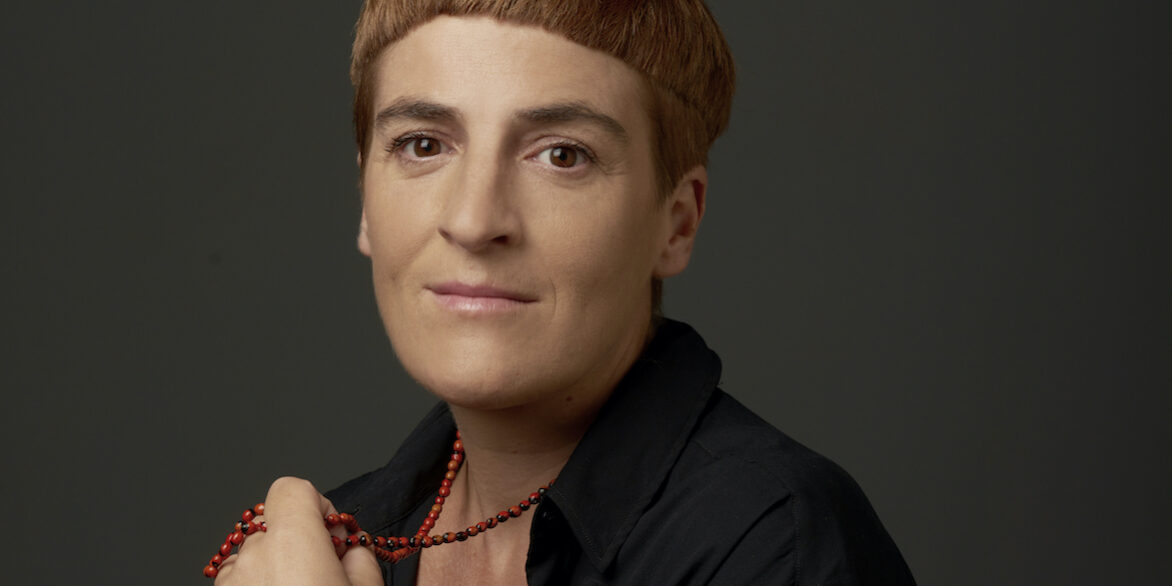

Candelaria Schamun on being intersex: “How much does a body have to endure to fit in?”

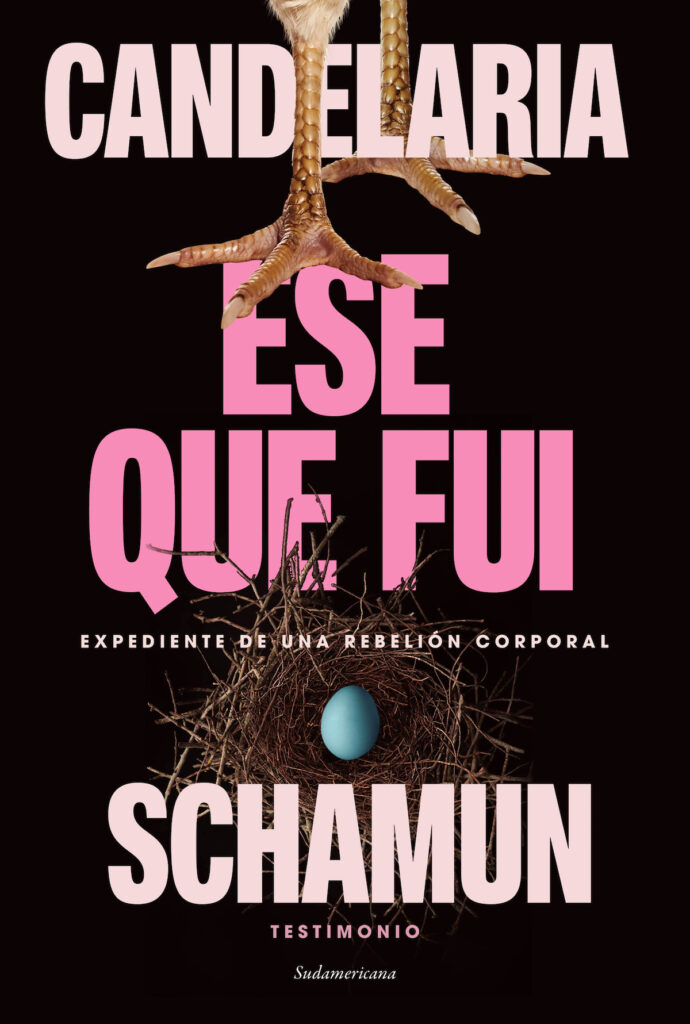

In her book "That Who I Was: File of a Bodily Rebellion," the Argentine journalist recounts how she discovered she is an intersex person and the paths she has had to travel to this day.

Share

At the 2019 National Women's Meeting in La Plata, Candelaria Schamun spoke out. She did so in the city where she was born and registered as Esteban. When she finished her story in the newly launched Intersexuality workshop, she sent a message to her friends: “I DID IT!”

That's when she knew she didn't have to keep telling her story in the third person or under the pseudonym "Vera." "I always felt the need to write it down. I told it to people I didn't know so they wouldn't reveal the secret that tormented me so much. At the Encuentro (Meeting), the reception was so wonderful that it made me realize I had to write the book in the first person," she said. And that's how Ese que fui. Expediente de una rebelión corporal (That Who I Was: File of a Bodily Rebellion ), published by Sudamericana in 2023, was born.

Candelaria is a writer and journalist. She worked as a crime reporter for Crítica, in the society section of Clarín, and as a producer for the television channel C5N. She is also the author of Cordero de dios (Lamb of God ), an investigation into the murder of Candela Sol Rodríguez. A few years ago, she left the field due to her disillusionment with media coverage of certain events, such as the disappearance of Santiago Maldonado. With this book, she returns to journalism from a different perspective and to tell her story.

At three months old, Candelaria underwent the first of four surgeries to "normalize" her body. She was born with sex characteristics different from those anatomically classified as "male" or "female"—in other words, she is intersex. She knew nothing about the implications of that and subsequent surgeries until, at age 17, she found a green folder titled "María Candelaria Health" in capital letters, containing part of her medical history and her birth certificate.

“For many years I could barely process it. I went through a very dark period, a time of self-harm, wondering what the hell I was: a monster . Until I started investigating my own identity. Now I lead a very peaceful life, but I also had a very dark life because I couldn't speak out. That's why it's so important to break the silence,” she shared from her backyard, nestled among a willow tree and fruit trees, where she lives with her partner, dogs, cats, and chickens in the province of Buenos Aires. In an interview with Presentes, she elaborated on the importance of this book and being able to share her experience.

– What did it mean to narrate your story in the first person?

– It was incredibly relieving. Not just for me, but for my family and friends. It was so many years of silence. Keeping a secret for so long is a huge undertaking; it takes a lot of your life. My mother's life was consumed by this. So the book is like a tribute to my mother and father, and a thank you to my whole family.

After the book was published, I opened up much more and began to love my body much more. That took several years of therapy, with feminism playing a key role. I always say that if you think you're intersex, or if you have a family member who is, or if you're the mother of an intersex person, the best thing you can do is reach out to the many organizations in Argentina that do amazing work. You'll find people who will listen to you, you'll find stories similar to your own. That helps a lot: getting out of the anonymity of feeling like you're the only person in the world.

– Why is it in gratitude to your parents? What role did they play in this whole story?

– I only truly grasped the magnitude of what my parents had done when I started writing and researching my own story. That's when I began to understand how they had put their own lives on hold so that I could continue mine and be happy, which I absolutely was. Despite everything, I had a wonderfully happy childhood. And that was thanks to them, to my siblings.

The pressure that parents of intersex children face, and continue to face, from the medical establishment and society, which demand bodies that conform to a "normal" standard, must be suffocating. Because parents of intersex children do everything the doctors tell them. It's not that they're crazy and want to harm their child. These are the medical recommendations they were given, and continue to be given.

– How does the medical system generally treat intersex people?

They don't give you any information. In my case, they didn't give me any information about what was happening. You go into an operating room without knowing what they're going to do to you. You know it's on your genitals, but not much more. You start to create an exaggerated scenario in your mind, imagining what might be happening to you, or not, but with your own imagination. On the other hand, you have no one to look up to. Intersex people often have very lonely childhoods. You think you're the only one, and that's horrible because you think you'll never have a peer. Genitals are always something shameful, and if you don't have anyone to look up to, you think you're monstrous.

Another common experience for intersex people is being studied. I think doctors study it in books, and when a case comes up, it's like, "Wow, this is what I studied." In my case, I had surgery with the best doctors in Argentina; it wasn't done in a garage. Intersex people can come from different social strata, from the provinces of Buenos Aires, La Pampa, or Neuquén, but more or less, there's a consistent code, a style guide.

– What is the objective of these interventions?

– For me, doctors live in the same society as everyone else, and that's what's taught at university. It seems to me that there's a society that can't tolerate bodies that might be born with some differences. How far does a body have to endure to fit into this society? Is it up to mutilation? To the point of losing all sensation? In my case, it was the elimination of pleasure . This and that have to be done for the body to be "normal," even if this person might lose genital sensitivity. These things aren't considered. A body is molded to fit the norm without considering the whole person.

Everything that was done was unnecessary. In my case, the only thing that was necessary was to stabilize me clinically. After three months, why did they have to perform genital mutilation? What was the risk to my life? None. These were surgeries that could have waited, done with more time and consultation. Human life and interventions are placed on the same level of urgency. And these are irreversible decisions that will likely cause that person lifelong post-traumatic stress disorder.

– To protect intersex children and adolescents from these cosmetic interventions, activists drafted the Comprehensive Protection of Sex Characteristics bill, which was never debated in Congress. Why is such legislation necessary?

– So that no more girls and boys are mutilated or subjected to unnecessary procedures. So that our identities and our bodies are respected, so that medical records are preserved and we can access them. So that parents receive accurate information about what is happening, so that doctors are trained with a broader perspective. Also, for access to healthcare. In my case, I don't have health insurance because if I disclose my underlying diagnosis, they start creating delays and charge exorbitant fees, and I can't even get coverage. This law is crucial.

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.