Cecilia Gentili: a book of letters and a life worthy of a film

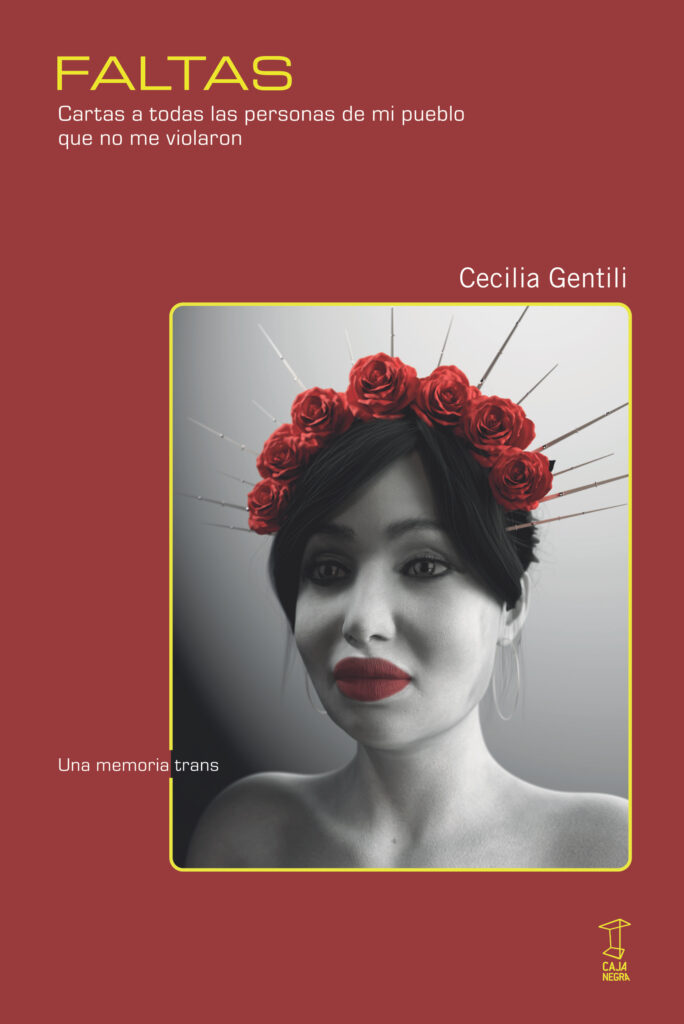

Following the death of the trans actress and activist for the rights of LGBTI+ migrants, the publishing house Caja Negra has released the book Faltas. "Cartas a todas las personas de mi pueblo que no me violaron" (Failures. Letters to all the people in my town who didn't rape me). In it, Gentili reminisces about her queer childhood in an Argentinian town.

Share

It was the 1970s in Gálvez, a town in south-central Santa Fe province. It was December, and as with every end of the school year, the schools had to prepare a Christmas play. In Argentina, a time of police edicts and forced disappearances, a boy of just six years old dreamed of playing the Virgin Mary, but he knew it wouldn't be easy. He had been called to the school administration and told, "You have a penis, and that makes you a boy."

He knew then that he would have to devise strategies to bend the laws that oppressed him. His first deception was directed at his teacher. With a self-sacrificing tone, he said that he would play one of the Three Wise Men, since no one else wanted to. And on the day of the performance, he arrived wearing a long, glittery cape, similar to the lavish dresses he would wear many years later when he played Miss Orlando in the American series POSE . That day, in that six-year-old boy, Cecilia Gentili first appeared and would never leave.

Many years would have to pass before Cecilia could settle in New York, become a renowned trans activist for the rights of migrants and LGBTQ+ people, and become the actress she had always dreamed of being. She died unexpectedly in February of this year, shortly after her birthday, while the publishing house Caja Negra was working on editing her book, Faltas. Cartas a todas las personas de mi pueblo que no me violaron (Failures: Letters to All the People in My Town Who Didn't Rape Me ), published in English in 2022 and winner of a Stonewall Book Award for nonfiction. At the time of her death, she was 52 years old and had lived a life worthy of a film.

More than 250 people attended the virtual vigil held in her name, where each participant shared an anecdote about her, and a joyous funeral was held at St. Patrick's Cathedral in New York, where Billy Porter sang. Because if Cecilia achieved anything throughout her life, which barely fits within the years she lived, it was to bring together diverse crowds: migrants, sex workers, trans and drag queens, transvestites, queer people. And she knew how to build families with them.

“Friends in misery”

Cecilia couldn't wait to leave Gálvez. When she finished high school, she moved to Rosario to study musical composition. There she reconnected with Norma Ambrosini, an old acquaintance from her hometown and the daughter of a friend of her mother's. She would spend her university years with her and confess her love for a man, telling her, "I fell in love with my girlfriend's brother." They were both united by their passion for the arts and their painful memories of Gálvez. They knew what it was like to go hungry, to struggle to make ends meet, to not be able to afford transportation to work. Both would also migrate to the United States in 2000 in search of a better life. And there they would go their separate ways. Norma would settle in California, and Cecilia would spend time in San Francisco before finally ending up in New York.

Cecilia began her new life as a sex worker and while battling her addictions. Later, she entered rehabilitation and obtained her citizenship. “It’s true that Ceci was an addict, that she did illegal work, but that also saved her life. It was during one of her prison stays that the psychologist or psychiatrist at the intake told her that she couldn’t send her to a women’s or men’s prison. That she had no documentation and nowhere to go. And she put an ankle monitor on her and sent her back home,” Norma Ambrosini recounts about those years.

From that moment on, freed from the abuse she suffered in each of those confinements and with no possibility of escape, Cecilia had to reflect on her identity, on her life in the United States, on who she wanted to be. “And that’s where her story of resilience begins,” Norma explains. From then on, she searched until she found the life she desired. She was part of an organization specializing in LGBTQ+ HIV/AIDS care, founded Transgender Equity Consulting and Apicha, and developed her artistic career, eventually starring in the acclaimed series POSE Red Ink on stage

Trans memoirs about a queer childhood

Now settled in New York, with a promising future and a large community supporting her, Cecilia felt compelled to delve into her past and write her memoirs about her queer childhood in the town of Santa Fe. These are harsh memories, marked by abuse, the scars of which have stayed with her throughout her life. This is how her book, Faltas (Failures), : a series of letters that seek to reveal secrets, expose traumas, accuse and redeem, teach and seduce.

The book compiles letters addressed to her abusers, but also to the network of people who contributed to those abuses through their silence. “I believe that the reason she wrote these letters was entirely personal; I think she wrote them to herself and didn't expect a response,” reflects Ambrosini, who, after Cecilia's death, was contacted by Caja Negra to assist with the book's publication. “I wanted to be a witness to her words being in the book. That was my mission.”

Is this a book written for Gálvez? Is she seeking revenge? Does she want to reach the town's ears? "We'll never know," Norma replies. "She loved to provoke and wanted to make a lot of people uncomfortable. Even me, when the publisher asked me if we should launch the book in Gálvez or not, even though I left before Ceci and, like her, never went back. If you ask me, I think this book was therapeutic; her work Red Ink came from it, and she wrote it to bring a chapter to a close."

“The idea that love hurts is absolute bullshit.”

Book dedications are clues: hints that guide the reader. Flaws. Letters to All the People in My Town Who Didn't Rape Me opens her heart with a dedication to Peter, the partner who was with Cecilia for the last ten years of her life. There, she thanks him for offering her his love during all that time, for reaffirming it every day, and for showing her "that the idea that love hurts is absolute bullshit." Perhaps the underlying theme that subtly accompanies this entire book. A truth she had to learn through pain.

Of all the letters in this book (to her abuser's daughter, to the boy who had sex with her but didn't kiss her, to the mother who prioritized appearances, to the village midwife), only two stand out for their brilliance. One is the letter to her grandmother, who was Indigenous and the only person who made her feel safe. During a visit with her, she tried on a wig and said, "This is what I want to be." Her grandmother replied that she looked perfect as she was. The other is the letter to Juan Pablo, who had also been systematically abused by the same man who abused her. He was the first person she could confide in about her suffering and with whom she could also share it—put it into words, to release it from within herself.

“The book could have been told without that letter, but it’s a relief. There was someone who accompanied her in that complaint, and although he wouldn’t have said anything if Ceci hadn’t asked him to, he understood that it was a pivotal moment for her and gave her the go-ahead to publish it,” Norma explains. In that letter, Ceci writes: “They are very serious letters, which made me see my life as something too bleak and terrible. So I thought of writing to you, and I couldn’t help but delve into this pleasure, as if only your name could bring me some happiness. I find it hard to think of you without a smile on my face.”

They were young and, at the time, the only gay men in town. Perhaps for that reason alone, their first encounter was sexual, and they soon realized that their bodies repelled each other. They then forged a deep friendship that Cecilia would cherish throughout her life. “This book tells an old story in her life and brought closure to her. It’s part of her activism, her legacy, her attempt to prevent others from going through the same thing. I didn’t know her writing process; I read it after it was published in English, and I told her it was a book I had to go in and out of many times. It made me laugh and cry,” says Norma.

Cecilia Gentili's final years and legacy

For Norma, one of Cecilia's main problems was her inability to say no to anything. “In her later years, she was extremely busy, wanting to do everything, eager to outrun the time she suspected she had lost. That's when I came in to edit this work so that the memories of our childhood in Gálvez wouldn't be lost. I think that busy life, that refusal to say no to anything, is what led her to falter at the end of her life.”

Faltas was circulating as a manifesto within the Latino community in North America, and Cecilia was already writing her second book with Valentino, Norma's son. They never saw her use drugs, nor were they part of her dark periods, because Cecilia wouldn't allow it. She distanced herself from them and protected them from that environment.

That's why Norma remembers her as always, as if no time had passed. In her memory, they still walk arm in arm down the avenues of New York, free and happy, whispering to each other, or they meet in her living room watching the Oscars, in a family scene, alongside her children who saw her as what she was to them: their aunt who dreamed of being Rita Hayworth, Anne Hathaway, or Zendaya.

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.