Indigenous women raise their voices 100 years after the Napalpí Massacre

It was one of the most tragic massacres in our history. What role did grandmothers play in transmitting memories? How did the Truth Trial come about? Was justice served? Qom and Moqoit women from Chaco recover the voices of their ancestors and reflect on the traces of silence, the past and present of a massacred territory.

Share

“I always wonder what that moment must have been like. And a whole movie plays out in my mind. Did my people wear running shoes to run through the mountains? Or did my ancestors walk barefoot among the thorns? Can you imagine the old women unable to run?”.

Fiorella Anahí Gómez, a young Qom artist and great-granddaughter of survivors, lights up when she talks about this. She lives in the Aboriginal Colony (Chaco) where the Napalpí Reduction was located, the epicenter of the massacre perpetrated on July 19 , 1924.

His grandmother Matilde Romualdo and his grandfather Salustiano Romualdo testified at the Truth Trial held in 2022. The verdict was simultaneously translated into the Qom and Moqoit languages, and Federal Judge Zunilda Niremperger of Resistencia ruled that the National State was responsible for the Napalpí Massacre. She considered it a crime against humanity committed within the framework of a genocide against Indigenous peoples . The ruling, among other preparatory measures, urged the National Congress to designate July 19 as the National Day of Commemoration of the Napalpí Massacre.

It was created during the "Napalpí: 100 Years After the Massacre" , organized by the UBACyT Project Memories, Resistances and Political Agencies of Indigenous Communities and Collectives.

What happened in Napalpí?

The “Napalpí Indian Reduction” was part of a concentration camp system used to subjugate the Indigenous population who survived the “Green Desert” Campaigns. There, the Indigenous population was subjected to forced labor: while the men had to clear hundreds of thousands of native trees with axes to supply the timber industry and the State itself, women and children were forced to work in the harvest, almost always of cotton. Reports from the time speak of violence, disease, hunger, and even torture. These were the living conditions imposed upon them by the State.

In 1924, hundreds of Qom and Moqoit indigenous people gathered in the Aguará area (within the mission) to protest a decree that prohibited them from working outside that territory. They also protested a reduction in the price of their crops, as well as issues related to health, food, and labor exploitation, among other things.

The Qom chiefs Dionisio Gómez and José Machado, and the Moqoit chiefs Pedro Maidana and Mercedes Dominga, engaged in dialogue with authorities as leaders of the protest. Meanwhile, the repressive forces of the State, with the support of Creole settlers, unleashed their full force by land and air upon the Indigenous people. It was the first time in Argentine history that an airplane had been used to repress a civilian population.

The hunt continued for days in the mountains. Bodies were burned in mass graves. Women and girls were raped. Testicles were mutilated and displayed as trophies. A terror took root, and silence became a collective survival strategy.

Viviana: Teaching and learning in a massacred territory

Viviana Notagay is Qom, a teacher, a mother, and a member of the Colonia Aborigen community. She works at School No. 14. “I built the school where I now teach. I was never told about the massacre. I heard it mentioned within my family, very briefly, because of the fear that existed. I only learned about it in my final year of teacher training, after an incident of discrimination against my siblings who spoke Napalpí. That led us to investigate the cause of the loss of our language, and that's when Napalpí came to light. We are Indigenous, but we were born in a territory that was massacred .”

When Viviana was a child, the Napalpí massacre was “absolutely unspoken.” Like other women, she began asking questions. Families acknowledged the massacre but couldn't identify as Indigenous. “They had to keep their culture silent to protect each other's lives .”

Patricia: “It was my grandmother who told the story”

Patricia Villalba, a Moqoit woman, was able to attend school until the third grade, but no one ever spoke to her about the massacre. She is from La Tigra, Chaco. Her grandmother did tell her stories. “My grandfather changed his name after the massacre. And he never said anything. He went to work, fed us, and that was it. My grandmother, Dorinda Gómez, was the one who told the stories. She told us that several people changed their names and even their ages because of the fear they had. It was said that those with white skin decided whether you would live .”

She has seven children and is separated. Months ago, she had to migrate to the greater Buenos Aires area in search of work so they could continue their studies. She lives in Avellaneda (Buenos Aires), caring for her 97-year-old grandmother. Her ex-partner, a criollo, never wanted Moqoit spoken in their home. “Only now am I telling my children the story of Napalpí. And how painful it was, the blood that was spilled from our communities, from our brothers and sisters, from my grandmother's family. There's still a need to make known what happened. The teachers don't know. Not everyone is as lucky as I was with my grandmother .”

How the community research was conducted

In 2008, Juan Chico and Mario Fernández published the first book by Qom people about the Napalpí massacre, “La voz de la sangre” (The Voice of Blood), written in Spanish and Qom la’aqtac. Two years later, Juan Chico—a historian, communicator, teacher, and Indigenous activist—mobilized other members of the community to get involved in the search for truth, a collective and community-based investigation into the massacre.

“In 2010,” Viviana recalls, “we had a conversation with Juan where he proposed we work on Napalpí, investigating who we are . That’s how the Renacer Napalpí group was born. We traveled around the territory collecting oral histories from people in the community. They told us, with pain, everything that had happened. My father, for example, recounted that his grandmother, Eme Ventura, told him that she had to bury half her body in the woods to hide .”

Fiorella: “Our grandparents knew, but out of fear they didn’t want to talk.”

That investigation reached the home of Fiorella, the Qom artist and great-granddaughter of survivors. “When Brother Juan arrived, my grandmother refused to speak. But she told me that her grandmother, Lorenza Molina, was there and saw how the women were raped and abused. And when she managed to escape, she was shot in the eye. She always showed the bullet scar on her arm. For a long time, they resisted in silence. It was wrong to talk about Napalpí . I saw non-Indigenous people coming in, investigating—journalists and historians—and the community itself knew nothing about that history. The only ones who knew were our grandparents, who didn't want to talk .”

Juan is a key figure in the recovery of Napalpí's history. "We were privileged that he was born in our territory," says Viviana, her voice filled with emotion. During these visits, they found Rosa Grillo, a centenarian survivor of the massacre . They interviewed her in 2018 with the Human Rights Unit of the Federal Prosecutor's Office in Resistencia, and her statement was incorporated as testimony. Juan died of Covid on June 12, 2021, and did not live to see the Truth Trial.

She died a year later.

Fiorella, for her part, encouraged her grandmother Matilde to testify. That day, the elderly woman asked one of the prosecutors if she would be arrested afterward. “They’re going to record me and then come looking for me with the police. What am I going to do? I’m old, what am I going to be doing in jail?” she said. The fear of reprisals, almost a century later, remained intact.

Viviana, Patricia, and Fiorella were at the former ESMA detention center in Buenos Aires, where two of the seven hearings of the trial were held. When they strolled through downtown Buenos Aires, they confirmed their suspicions: almost no one knew what had happened in Napalpí, nor was the Truth Trial widely known.

Indigenous women, representations and leadership

For all three interviewees, Indigenous women's leadership is relatively new. While Cacica Mercedes Dominga is a historical emblem of the Moqoit people , Patricia believes that occupying positions of representation “is new for Indigenous women . Nobody imagines that I went to the Truth Trial. The community doesn't really know. In my neighborhood, they hardly accept who they are, Indigenous people. Nobody speaks Moqoit there, precisely because of history and discrimination.”

Fiorella points out that “many question why we don’t speak the language. How can they be from an Indigenous community and not speak the language? And that hurts because we have a history that explains why our mother tongue was buried: because anyone who spoke it was hunted down .”

Talking about Napalpí isn't easy. "The questions are simple, but the answers are very difficult," says Patricia, who feels "a mixture of anger, pain, and helplessness" when she remembers the massacre. "There's no explanation for such cruelty, for having no mercy and killing so many innocent children, grandparents, and parents. I'm proud to be from the Moqoit people, to be a descendant of some of the survivors of Napalpí. What I would have given to have my grandmother here and tell her that justice was served, that the truth came out .

All three agree: truth is not a goal but a foundation upon which to build a more just life for the community. Patricia emphasizes: “ Gender-based murders continue to happen in our community. Some come to light, and others don't; they remain in fear, and no one does anything .” And Fiorella adds that “Indigenous girls are raped and discarded like garbage. The news reports say that non-Indigenous people go out to ‘hunt’ Indigenous people. It's awful. It's still happening.”

What happened after the Truth Trial

Are the reparations measures ordered by the court being implemented? Has life changed for the community of the Indigenous Colony? “There is no historical reparation,” Patricia says, “ if there are no schools, proper streets, a community center, or potable water . Our territories are being taken over by foreigners, small producers are selling their land, and our natural resources are being depleted. Without a national awareness of the horrific events in our history, they will continue to take our lands .”

Viviana believes that “beyond the resistance, the consequences of the massacre remain intact. For example, the lack of access to healthcare, education, and housing. And today we continue to demand dignity for our communities. We demand that the State recognize each community's full right to access justice .”

“Getting to a Truth Trial was not easy at all,” the teacher reflects. “It was a difficult process. It is rewarding that the State recognizes that it committed genocide against our Indigenous peoples, that we are part of a history that was never told. They wanted to exterminate us. And our ancestors endured in silence. They remained and resisted. That is why we are here.”.

Nache aỹem lquicỹaxaqui so'

Gomez, Machado, Maidana, Dominga

qataq som qalota maye mashe qaica toteguepi.

Se'eso pee, so nte'eta yem Napa'lpi.

Aỹem ipataqo'ot ana cotapicpi togoshaapec,

qataq anam toclate'epi, aỹalai' qataq aram mapic

mayen qolguete' ra saishet ra qaicoua'ai.

Aỹem Napa'lpi, aỹem tounaqqui, aỹem ncuennataxat,

ñaq aỹemmta aỹem tenaxat, aỹemla'alaxac so bonexoc.

Aỹem Napa'lpi

I am the truncated claim of

Gómez, Machado, Maidana, Dominga

And so many others who are no longer here

The long night

From the morning in Napalpí

It captivates me, along with those ancient quebracho trees

Beside the thistle patch, beside the lapacho trees

That Mapic already

That does not want to be forgotten

I am Napalpí, I am memory, I am recollection

I am present, I am hope

I am a cry for freedom

I am Napalpí.

Excerpt from Ayem Napa´lpi / I am Napalpí, by Juan Chico.

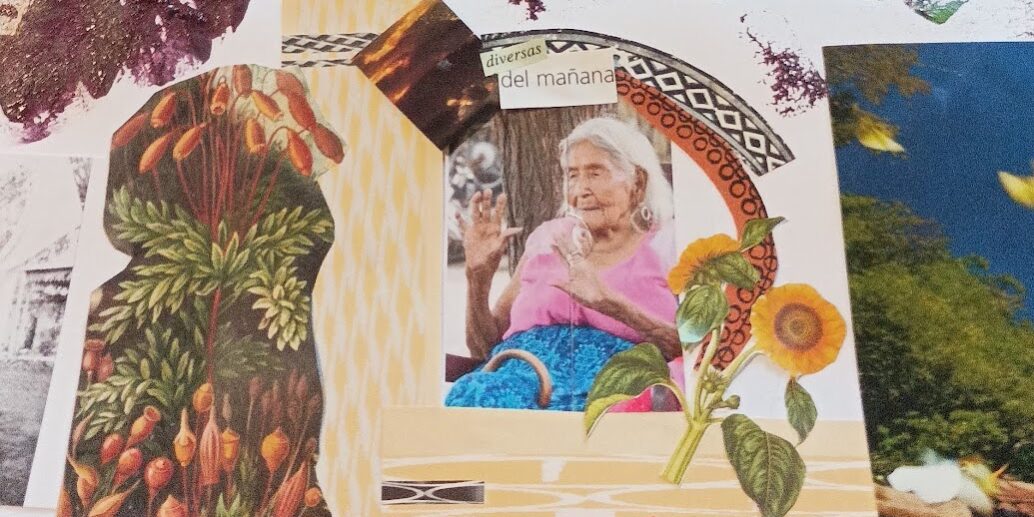

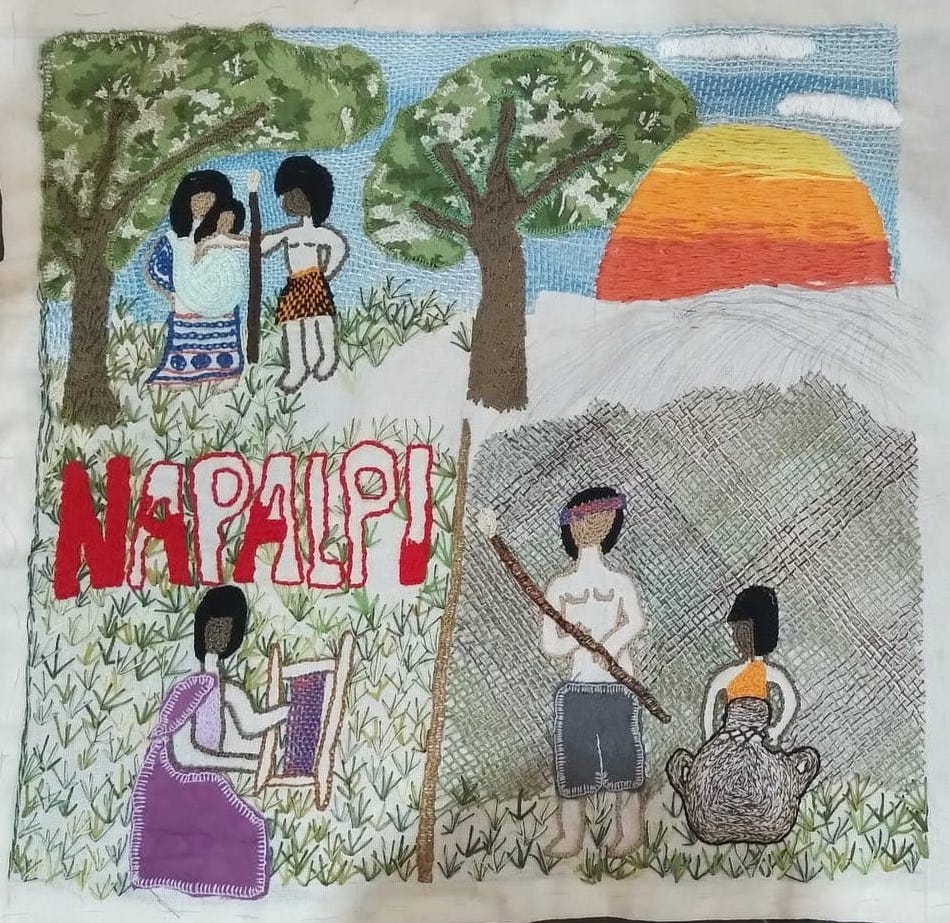

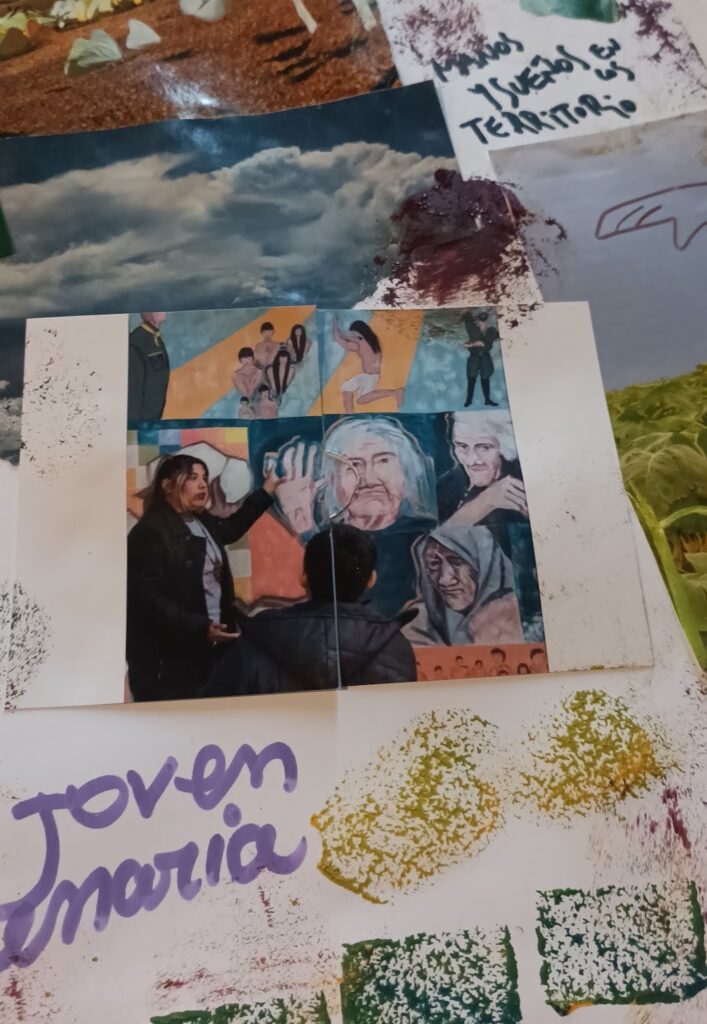

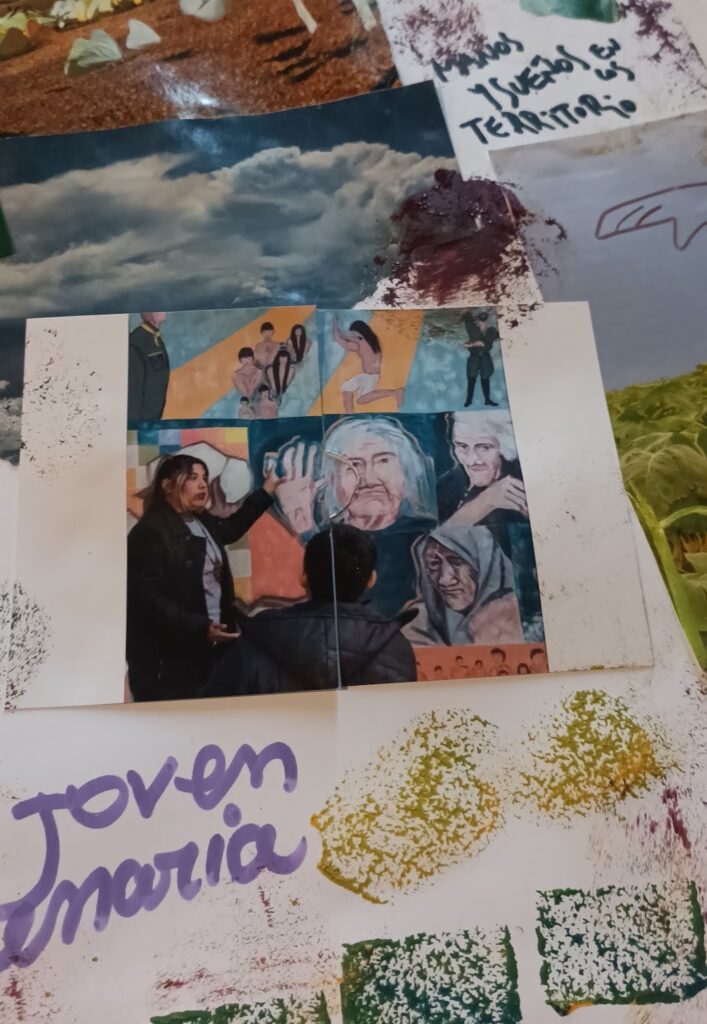

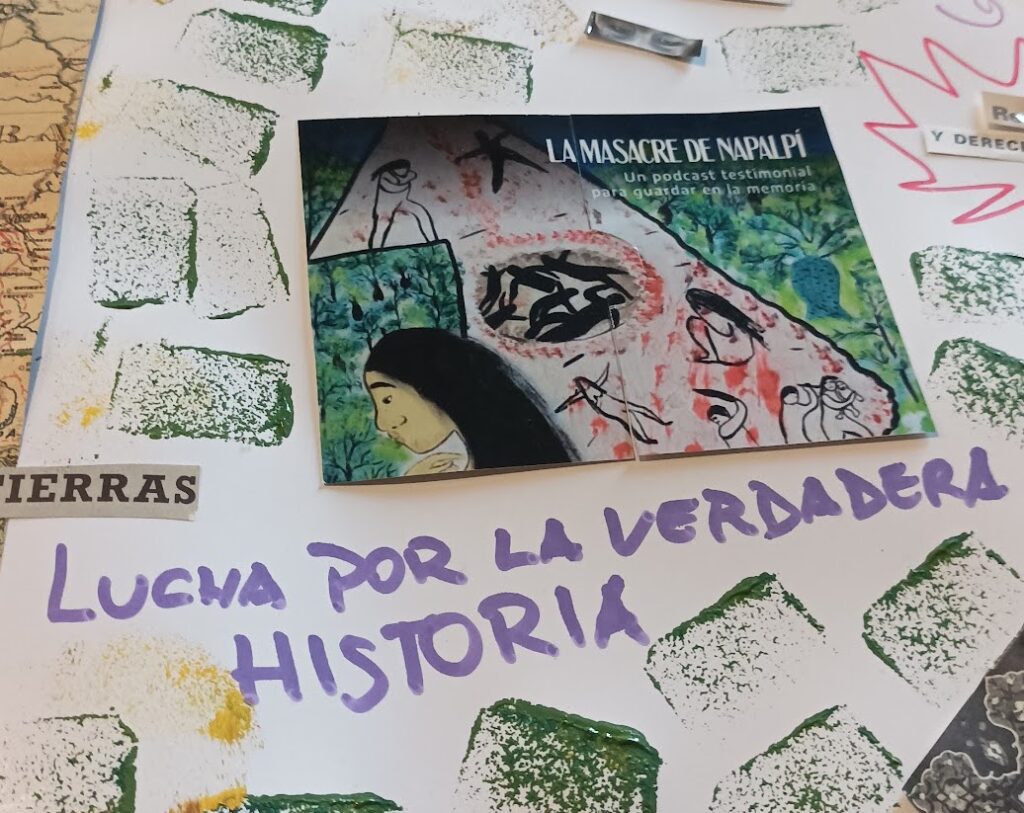

This article is illustrated with works from " Embroidering Struggles of Yesterday and Today ," a traveling exhibition by the "Embroidering Struggles" collective, on display until August 12 at the Ethnographic Museum, Moreno 350 (CABA). It also includes fragments of the collective mural created at the Paco Urondo Cultural Center as part of the "Napalpí: 100 Years After the Massacre" , organized by the UBACyT Project on Memories, Resistance, and Political Agency of Indigenous Communities and Collectives. The photographs were taken by Florencia Marmissolle and Luciana Mignoli.

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.