Rosana Paulino: Black women at the center of art to heal Brazil's traumas

The Afro-Brazilian artist is exhibiting an anthological show at Malba: the most important outside of Brazil, where she explores the collective trauma of slavery.

Share

When Brazilian artist and professor Rosana Paulino (São Paulo, 1967) was a child, she couldn't play with Black dolls—they didn't exist—nor watch films with Black protagonists who weren't servants. In Brazil, one of the last countries to abolish slavery in 1888, the colonial past and its impact on Black culture remain a major point of contention and silence. With the end of the slave trade, official archives documenting these policies were destroyed. Among these records were the daguerreotypes of Auguste Stahl, an imperial photographer who worked for the Swiss scientist Louis Agassiz. Agassiz claimed that there were superior and inferior races, providing a perfect theoretical framework for the exploitation of certain people.

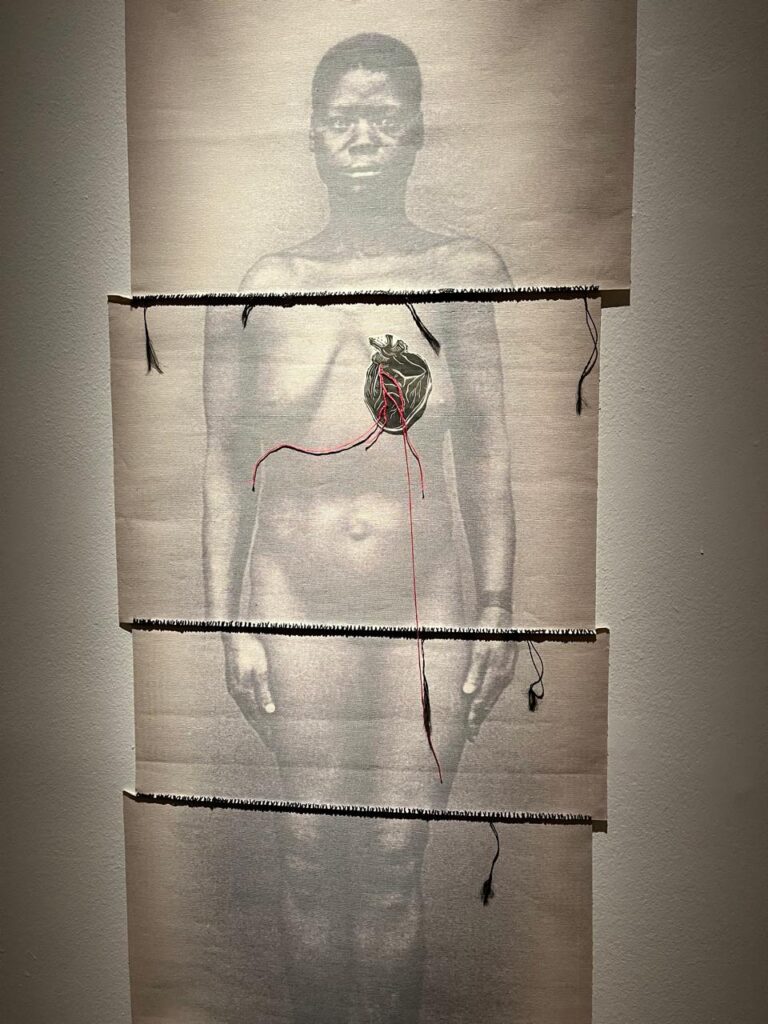

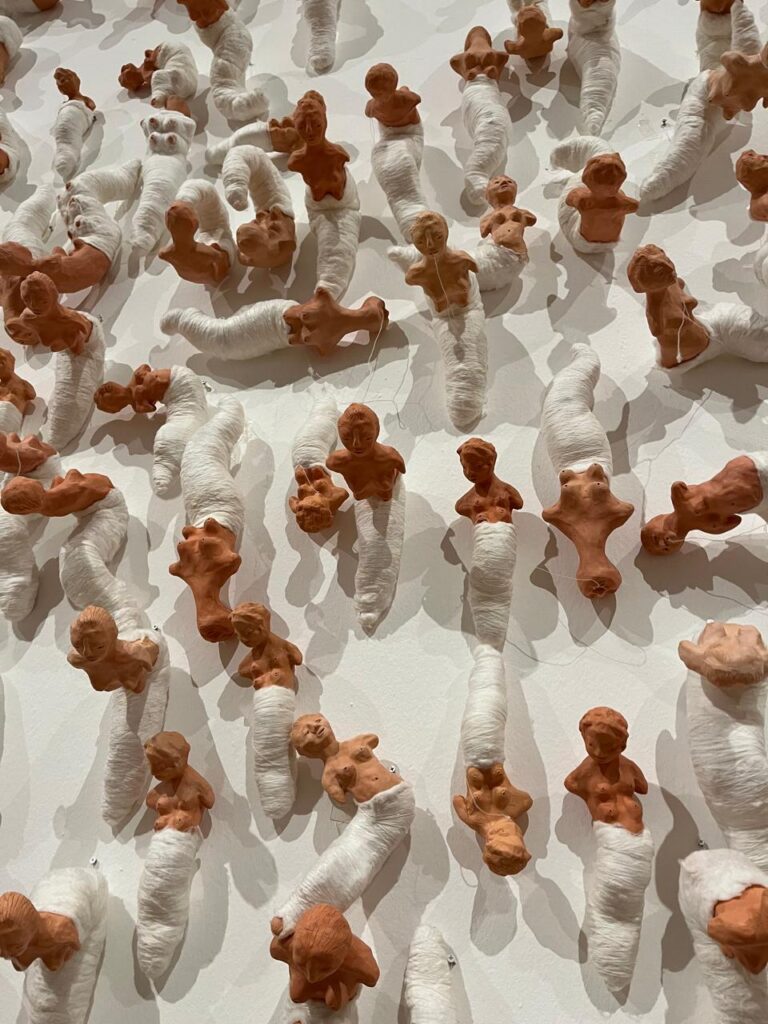

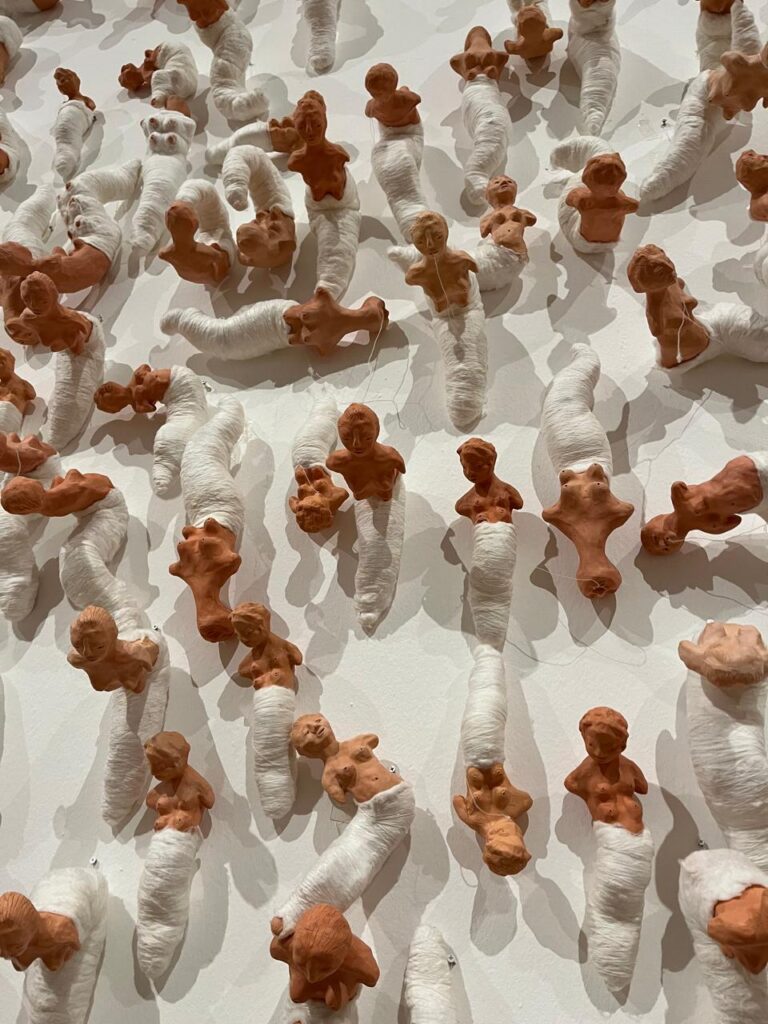

Not all was lost: after researching and searching through various archives, Paulino recovered several of these photos. He made giant prints of the naked women's bodies, cut them into pieces, stitched them together, and drew on some organs: sometimes the heart, sometimes the uterus. These photos are part of “ Amefricana ,” a powerful retrospective exhibition that brings together 80 works by the Brazilian artist at the Museum of Latin American Art of Buenos Aires (MALBA). It is the first time a Black artist has had a retrospective exhibition at MALBA and the artist's most important exhibition outside of Brazil .

Divided into two rooms, the exhibition's layout is thematic rather than chronological: "Sutures," "Settlement," "Archives," and "Brazilian Geometry" are some of the sections. There, the artist's diverse techniques—prints, photographs, ceramics, drawings, videos, and paintings—are displayed, along with the trajectories of her research and thought. Paulino delves into the intersections of racism, gender, science, and memory. "I am a visual artist . That means that everything I think or feel, I then have to figure out how to transform into an image , she said in a public interview alongside the exhibition's curators, Andrea Gentili and Igor Simões.

First sutures

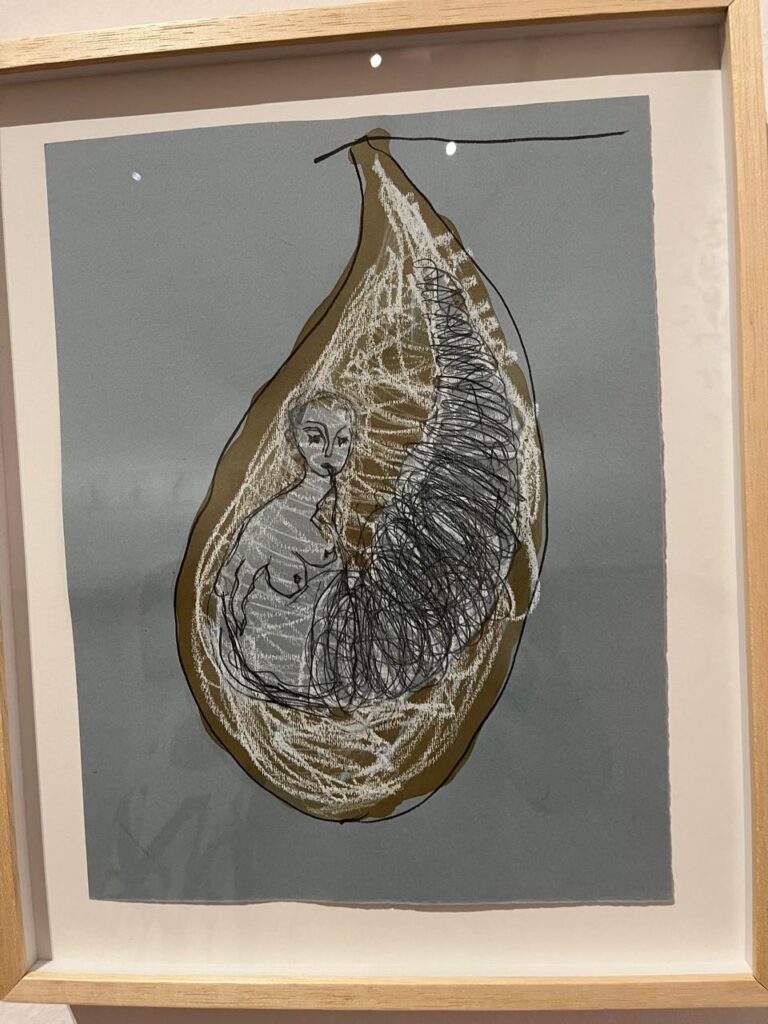

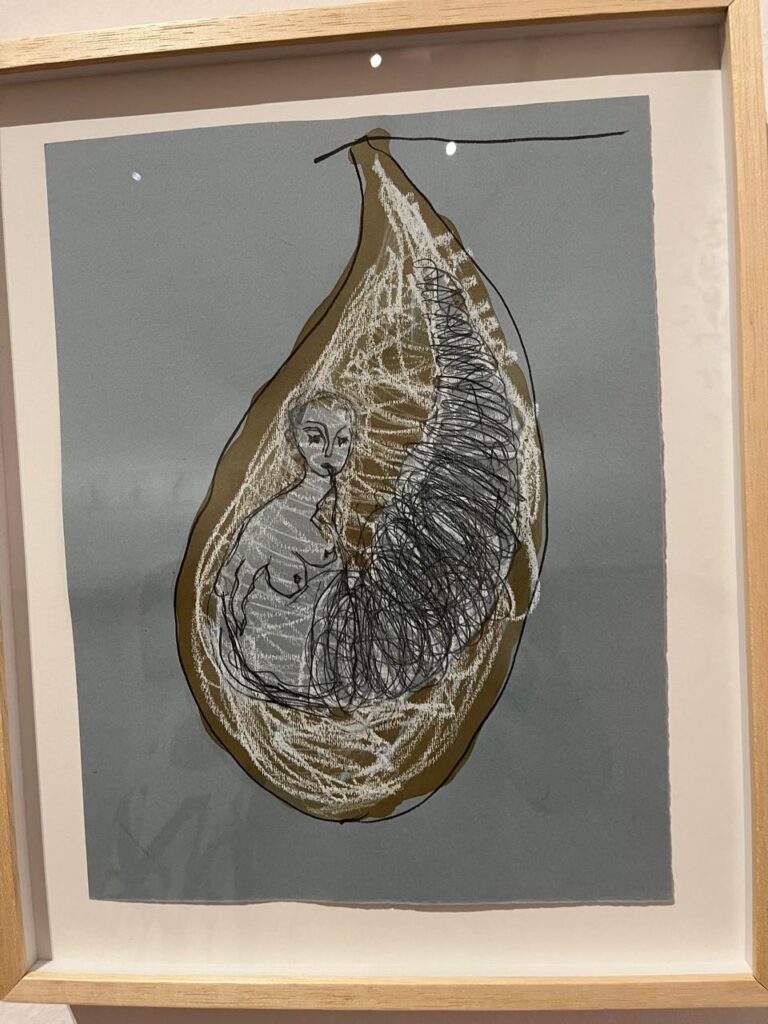

When she was starting out in art, her sister worked with women who were victims of gender-based violence. Her sister's stories resonated deeply with Paulino, and she felt she had to translate those painful narratives into images. This is how “Sutures” came about. “The stitches—which I prefer to call sutures— in some pieces highlight the problem that Brazil is a country that has never concerned itself with providing compensation to communities that have been marginalized and dispossessed . It is a country that wants to forcibly 'unite' the different populations that live here, and for that, it has resorted to systematic state violence. I always say that Brazil is often like a Frankenstein, in which disparate parts, which don't come together, are forcibly sewn together to try to create a common body . Obviously, that's not going to work,” Paulino says in the curatorial text.

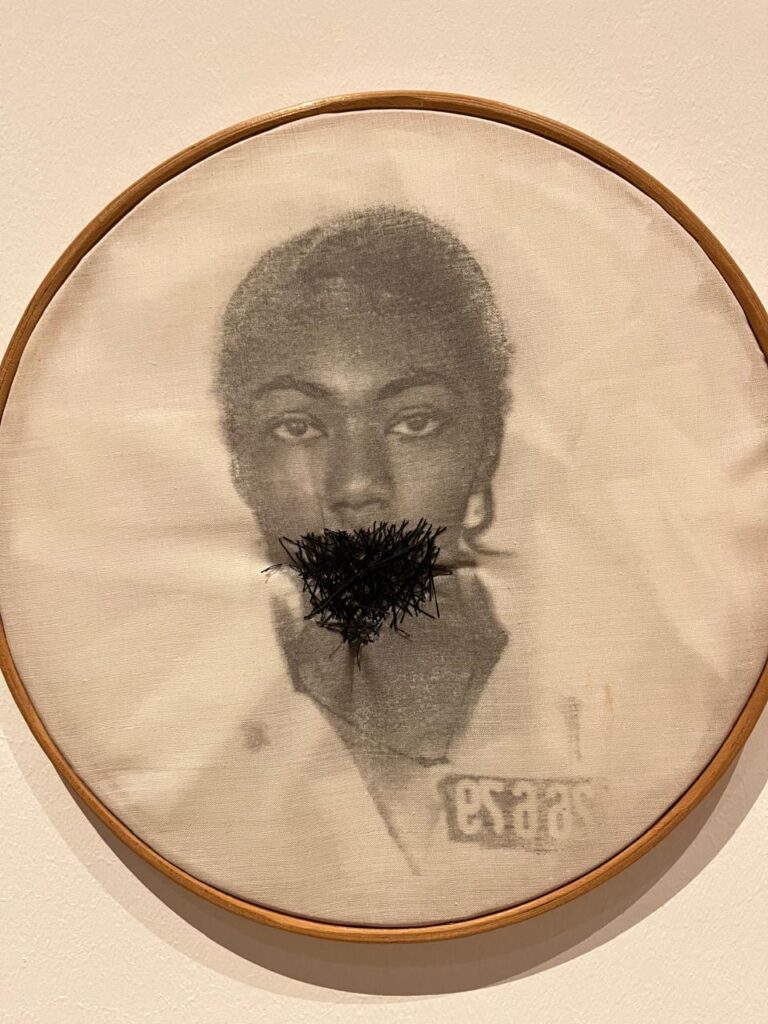

The first photos he worked on in a frame were those of his family – he hadn't found any others yet – and from there the project grew from the personal to the national, the same political gesture.

“ When you think of embroidery, you think of a white woman sitting quietly, but I was discussing violence, and so I stitched. I stitched the eyes, because these women often can't see, I stitched their mouths, because they can't speak . I started with my family, but I realized I could talk about how the country views Black women. I needed to understand who I am and what my culture is. I needed to be an artist to be able to talk about things that couldn't be talked about ,” she says.

Natural histories, official histories

Before becoming an artist, Paulino wanted to be a scientist, driven by an enormous curiosity for biology and the insect world—interests she never lost and which she integrates into her explorations. Today, nature is at the heart of her art, first as a deconstruction of those supposedly scientific narratives used to justify horrors (this is the subject of her book “Natural History?” ) and also as a possibility for transformation, as shown in her drawings of mangrove-women and the dozens of ceramic pieces of nude female torsos emerging from cocoons.

“When I was a girl, my mother embroidered and sewed to pay for our studies. She embroidered at night. To me, it was like watching a huge spider pulling threads from within. It was what allowed her to pay for her daughters' education. It was the family's protection. I wondered how to transform that into images,” Paulino said. “ Life is constantly changing ,” she added.

Another narrative that Paulino explores in her work is Brazilian art, particularly its geometric forms. The artist responds to the cultural and artistic establishment that once proclaimed Brazil a modern country, integrated into the world through its abstract painting and sculpture. “ While a group of white artists in Rio and São Paulo considered themselves modern because they used geometric forms, many parts of Brazil remained feudal. Brazil has always had a tendency to copy ideas from abroad. We also had the geometric forms of Black and Indigenous communities, but these were silenced. So this work is a critique of a country that remains unseen ,” the artist explains.

Memory to live by now

Paulino has been a pioneer in her country in placing Black culture at the center of artistic discussion and turning it into an exercise in memory. She speaks of slavery as a collective trauma that affects not only the Black population but all who live and have lived in Brazil .

“It’s impossible to think about the present or the future without thinking about the past. The current data we have in Brazil is terrifying; police violence against Black people is an everyday occurrence. And until two generations ago, Portuguese wasn’t spoken in my family. My great-grandmother spoke African languages. We need education, public policies, and time. Because Brazilian society still clings to the idea of slavery today.”

Americana can be visited at the Malba until June 10.

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.