Matías Santana, from student activism to the Mapuche cause: “I am a political prisoner”

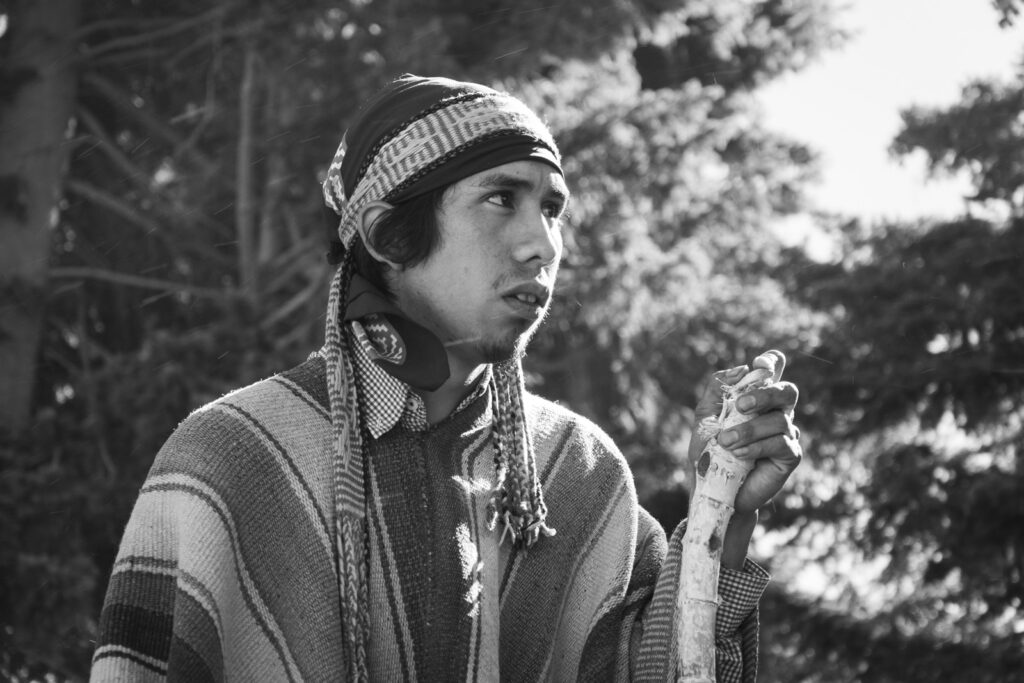

Matías Santana became known to the media through the Santiago Maldonado case, a crucial witness in a case that the courts recently ordered reopened. He was caricatured as "the Mapuche with binoculars," but his activism began several years earlier. He has been held in pretrial detention for three months at Unit 14 in Esquel. Mapuche communities are calling for his release.

Share

ESQUEL, Chubut. At first glance, the alpine-style Unit 14 of the Federal Penitentiary Service in Esquel resembles the tourist attractions that abound in this city in the province of Chubut. A wooden cabin, a green, gabled corrugated iron roof, a corner with pine trees, and the snow-capped peaks of the surrounding mountains. Inside is Matías Santana, a 27-year-old Mapuche man. He didn't come to this city like so many others to experience the breathtaking beauty of Los Alerces National Park (a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 2017), its lakes, and ancient trees, just a few kilometers away. Matías arrived in Esquel deprived of his freedom, days after his arrest in Bariloche on February 17, 2024, for defending those territories enjoyed by tourists.

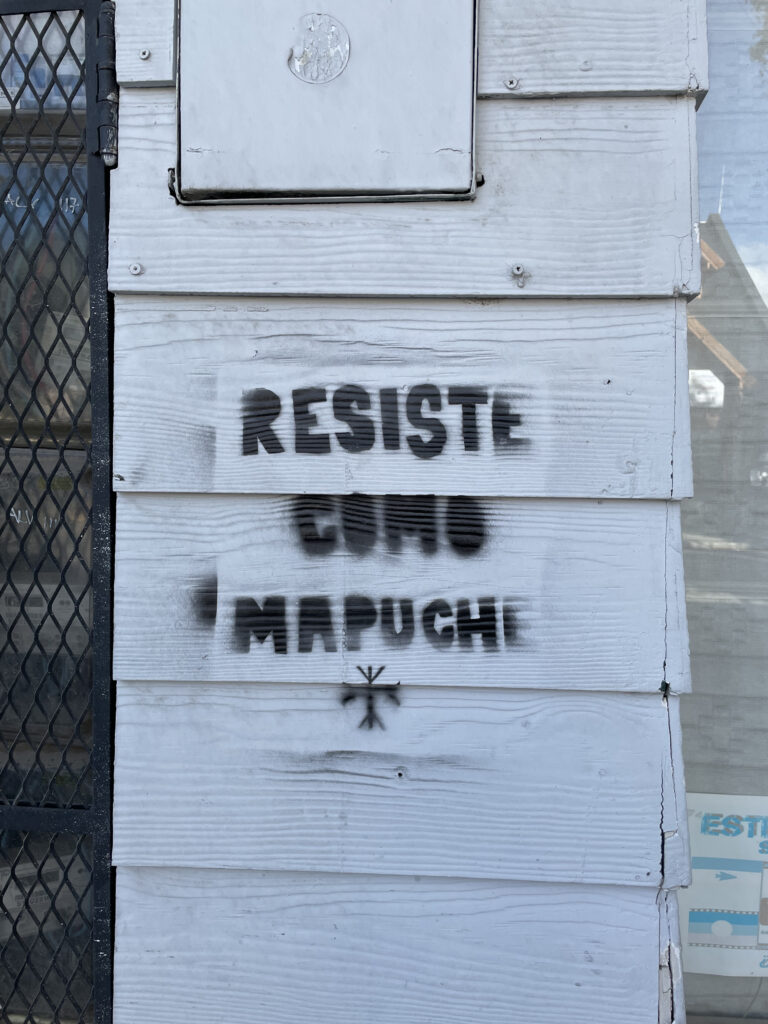

He is considered a political prisoner. Mapuche communities in Patagonia are demanding his release and have been carrying out various protest actions.

“I’m not here for being a thief, a drug dealer, or for raping anyone. I’m here to defend a right ,” he says one Sunday afternoon in the multipurpose room where detainees receive visits under strict security measures. There are only two tables with families. At Matías’s table is his father, with whom he recently reconnected after being estranged for many years. His name is Cristian; he’s a construction worker and a member of the evangelical church.

"I stopped seeing him when he was 4 or 5 years old," says Cristian.

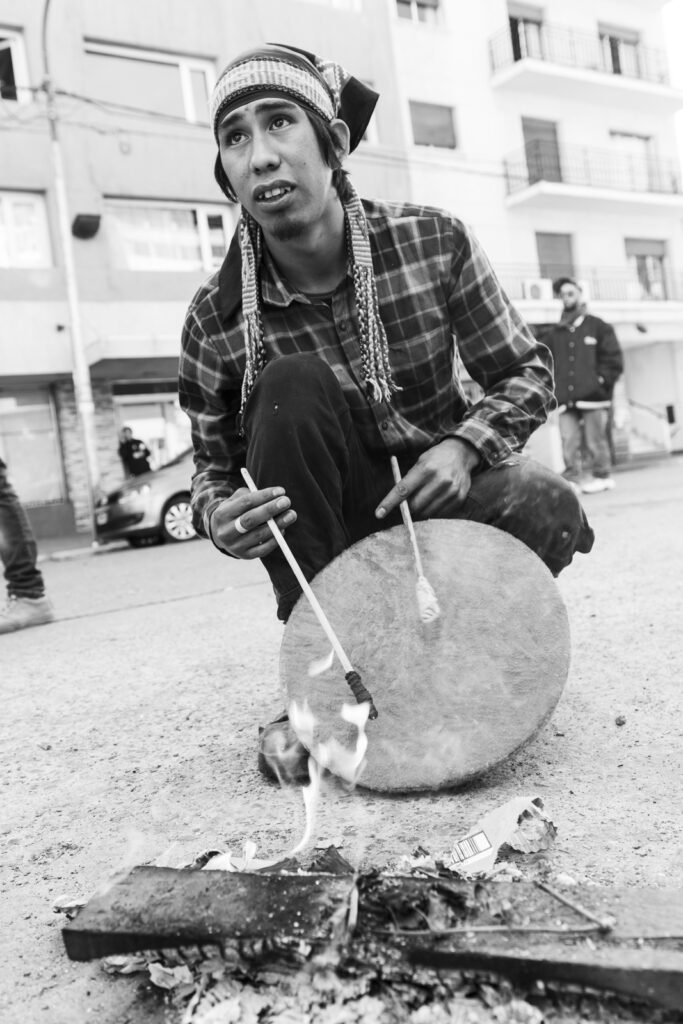

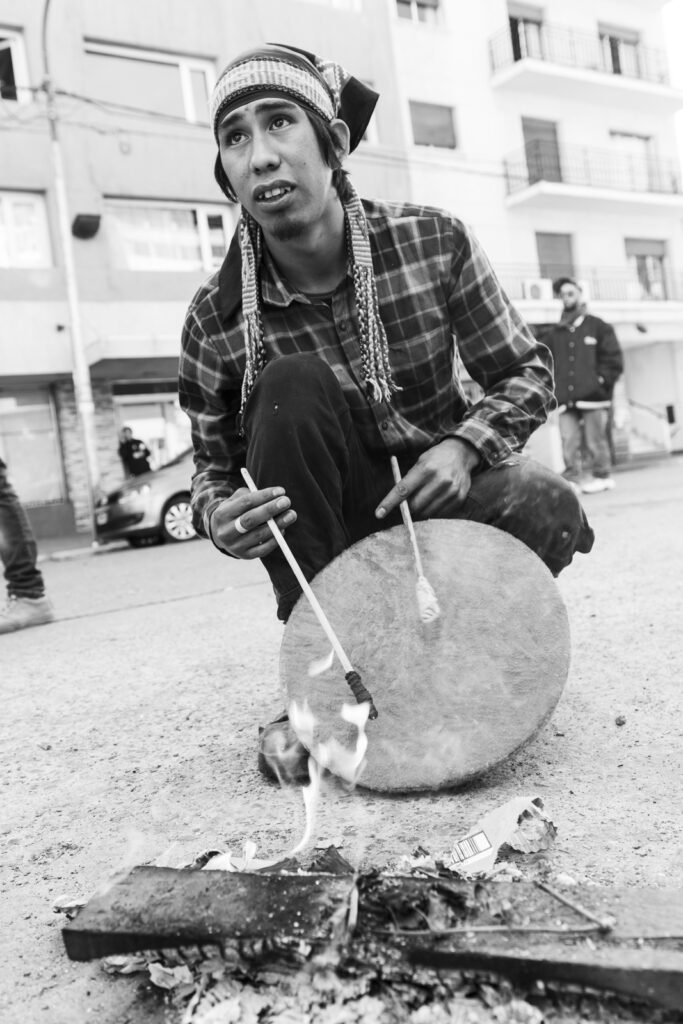

Matías smiles serenely as he prepares a mate gourd, half blue and half fuchsia, made of plastic. His black eyebrows and eyelashes are framed by a trarilonco, a red wool headband woven on a loom and embroidered with Mapuche iconography: two eyes. One open, one closed. Looking outward and inward at the same time , he will explain later.

He wears a blue plaid shirt and a bracelet with seashells on his right wrist. Matías's hands are his tools of the trade in prison, where he conducts carpentry, plumbing, and baking workshops, for which he receives 40,000 pesos a month.

–I wasn't the first Mapuche imprisoned, nor will I be the last in this prison.

Also present is a friend from years ago, Beto, who hitchhiked from Puerto Madryn. Matías and Beto shared the first winters when they recognized themselves as Mapuche. Matías's father speaks very little, Beto even less. At the table, they share pastries, bread, mortadella, salami, and sweet potato jam, which Matías barely touches. When the water for Mars runs out, at some point he'll sweetly ask Beto: " Little brother, will you bring us some water?"

In this prison, he's one of the people who receives the most visitors, although it gets harder over time. Solidarity networks send him food, which he shares with his fellow inmates. "If we ate the meager rations they give us, we'd be malnourished," he says. They also bring him hygiene items, notebooks, and books.

What is he accused of?

Matías is currently in pretrial detention on two charges. The first and most high-profile charge: he is accused of illegally occupying the La Escondida ranch and the former Mascardi Hotel in 2018, as part of the Lof Winkul Mapu land claim in Villa Mascardi (Río Negro province). In this case, Matías, Celeste Guenumil, Luciana Jaramillo, Romina Rosas, Yessica Bonnefoi and Betiana Colhuan , a Mapuche spiritual leader, Matías's partner, and the mother of his two children, have been indicted. The trial is expected to begin at the end of June, although the date has been repeatedly postponed.

In November 2017, the community settled 300 meters from Lake Mascardi, on seven hectares of Nahuel Huapi National Park. The machi Betiana had been shown this place through her dreams.

On November 23, a partial eviction began in Lof Winkul Mapu, which turned into a brutal crackdown. Two days later, on the 25th, the Albatros Group of the National Prefecture entered the property and opened fire with live ammunition, killing 22-year-old Rafael Nahuel by shooting him in the back. Rafael was the cousin of Betiana, the first machi (Mapuche spiritual leader) to emerge in many years on this side of the Andes. Five years later, she was one of six Mapuche women who, on October 4, 2022, suffered another violent eviction, after which they were imprisoned for eight months.

Following a dialogue between the Secretariat of Human Rights (during Alberto Fernández's administration), the community, and human rights defenders, a settlement agreement was reached in June 2023 between the State and authorities representing the Lof Winkul Mapu community. This agreement resulted in the dismissal of the case against the Mapuche leader for trespassing on National Parks land and the return of the rewe , her ceremonial space, to the machi (Mapuche spiritual leader). However, this agreement was not ratified by the judge presiding over the trial at the end of June for the alleged trespassing of the Hotel Mascardi and the La Escondida ranch (brought by private plaintiffs). Therefore, Matías (and the six Mapuche women arrested in 2022) will also be tried for trespassing on National Parks land.

The judge's refusal to enforce the settlement agreement is not an isolated case: according to the Lawyers' Association, the judiciary is not impartial. It responds to the interests of local businesspeople and politicians grouped in organizations such as Consenso Bariloche and Consenso Patagonia. These organizations are controlled by powerful sectors of the provincial economy that dominate the tourism, real estate, financial, forestry, and construction industries. They have the support of politicians from the PRO party and La Libertad Avanza, as was evident in Patricia Bullrich's participation in an anti-Mapuche march with xenophobic slogans on October 2, 2022.

Adding to the Judiciary's refusal to enforce the settlement agreement, the new head of National Parks, Cristian Larsen, announced that he had terminated the agreement on May 10. Furthermore, the national government has prohibited the display of any flags other than the Argentine flag.

The other charge against Matías is for resisting authority during a march in Cushamen. In this case, he was granted probation: if he completed community service, the case would be dismissed and he would be acquitted. However, this was overturned because the place where he began performing community service closed, the receipts were lost, and the person in charge left.

The capture

Matías's name began to circulate widely in recent years. He provided crucial testimony in the disappearance and death of Santiago Maldonado, both while Maldonado was missing and before his body was found in the Chubut River. His cousin, Facundo Jones Huala, is known to the Argentine and Chilean justice systems, as well as to Matías's fellow inmates. Facundo spent 11 months in this prison and was extradited to Chile in January, where he is serving a sentence.

–Here I am with people who have already lived with a Mapuche prisoner. They have an idea of how I operate and my worldview. There are different relationships here with the other prisoners. With some areas it's harder to talk, and with others everything's fine. But I'm better off than when I was locked up in the PSA (Airport Security Police) in Bariloche for a week, right after they arrested me.

His capture was front-page news on many websites and by the Ministry of Security, which publicized it along with a video equating the Mapuche struggle with the actions of drug cartels in Rosario and the piquetero movement. " Enough of terrorists disguised as Mapuches in Argentina!" said Security Minister Patricia Bullrich on her social media .

"I was arrested by the Federal Police in Bariloche. I'm grateful they brought me in because they could have shot me. They could have followed another procedure, too."

That February morning was cold, and since it was a Saturday, Matías drove his partner, the machi, to the market in downtown Bariloche, where she sells products from her natural cosmetics business. After dropping her off, he drove back with his children. “I was with the two boys and I had to buy things for breakfast.” They had barely gone a few meters when he noticed they were being followed by a gray pickup truck. Suddenly, someone yelled, “Stop!” and his name.

–Matías Santana!

-No no.

The first reaction was to deny that it was him.

The truck pulled up alongside the car. The gun was pointed at his head.

–Santana!

Police officers appeared everywhere.

–Yes. Well, Santana. I'm Santana.

The eldest son grabbed his hand.

"I've already lost. I just want my children to be taken to their mother. She's two blocks away."

–Surrender.

Matías handed over the car keys.

"I need to talk to their mother. Who am I going to leave my children with? I'm calm. I don't want my children to see violence."

Matías got out of the car and surrendered with his arms outstretched.

“That’s when they started hitting me. The children were screaming. The machi arrived. On top of that, they couldn’t put the handcuffs on me.”

The machi repeated:

—We cannot be usurpers within our own territory, on our own land. We are fighting to defend a sacred ceremonial space, our rewe. We are not terrorists, we are Mapuche defending our territory, our lives, and our water.

“I kept insisting: they have to tell me what the charge is. It was an illegal arrest.”

Matías was good at escaping. He had been a fugitive for a year and three months. First, they transferred him to the Federal Police and then to the Airport Security Police (PSA) in Bariloche. He spent the first six days in a tiny cell, without windows; he couldn't listen to the radio or drink mate. They took away the books they had given him and searched him four times a day. They escorted him to the bathroom with shields and machine guns, he says. Through that wall where he watched the hours pass, he heard: “ We're going to get this little Indian .”

He asked the authorities for respectful treatment. He managed to get them to change those guarding him. “They put older people in charge. ‘Try to fight for your freedom ,’ they told me. They let me shower without my hands and feet cuffed.”

From there he went to the Esquel prison.

The psychologist kept asking me, "But do you acknowledge the crime?" And I explained that I didn't. I didn't commit a crime. I was asserting a right. Legally, it might be considered usurpation , but they have to understand that the 1994 Constitution and ILO Convention 169 recognize the communal ownership of indigenous peoples. We should be in a different situation. Indigenous peoples should be able to engage in dialogue with the State.

“Land, justice, culture and freedom”

Matías's story could be, as he says, the story "of any kid from the suburbs." A boy from a very humble home, raised by his mother, his uncle, and his grandmother Trinidad Huala, who was born in Cushamen, lives in Esquel, and has been very ill in recent weeks.

Matías was born in Esquel. When he was eight years old, his mother moved to Sarmiento to find work. Sarmiento is a fertile valley in the south of Chubut province, steeped in history: a petrified forest, a paleontological park, and rock art. His mother cleaned houses and still lives there.

Matías stayed with his family in Esquel. Esquel isn't just any city. It's a tourist hotspot and also a crucial hub for environmental activism. On every block there's some sign, flyer, sticker, mural, graffiti, or reminder of a collective decision, which can be read on some shop windows, businesses, street corners, houses, and cars: NO TO THE MINE .

Esquel is connected to Bariloche by the iconic Route 40, which originates in Santa Cruz province, runs along the foothills of the Andes Mountains, and stretches from Patagonia to the Puna plateau and the Bolivian border. The stretch between Esquel and Bariloche is as beautiful and pristine as it is coveted for its water sources. It is the gateway to three national parks: Los Alerces, Puelo, and Nahuel Huapi. The Mapuche people claim part of these ancestral territories, where in recent years the splendor of the landscape has served as the backdrop for a complex web of inequality, death, violence, and economic interests.

–The issue of the mine affected the entire community of Esquel closely. I remember as a child riding piggyback on Mauro Millán at the demonstrations, and also going with Facundo, my cousin.

–What sparked your awakening to activism?

"Sarmiento's 105.5," he says with a smile.

Matías's activism did not begin with the Mapuche cause, although his grandmother spoke Mapudungun at home.

“I had gone to visit my mother, and I wandered into that radio station, which was also a safe space for kids with substance abuse problems. I came back with the idea of doing that in Esquel. I went to School 151, which had an annex at the prison. Recess meant going to the hallway, which was very uncomfortable. At 14, I decided to intensify the student activism—something that had waned in the 90s—and I would talk to administrators and students to improve the learning conditions. The film 'Night of the Pencils' had a profound impact on me.”

He believes his first revolutionary act was overthrowing a director who did nothing for the students. He had lost the student union elections, but that didn't stop him. He and a friend organized demonstrations on Tuesdays, and young people from other neighborhoods came to join them.

In his second year, Matías dropped out of school, which he is now trying to finish in prison. His activism became grassroots with the young people of Guanacos en Pie, a youth organization founded in 2012 to mobilize against mining projects.

–We started the land occupation to address the housing shortage. I lived in the Don Bosco neighborhood. I was 15 years old… I've been a social activist for a long time. I managed to bring electricity and water to the area.

Matías listened to punk bands like the Spanish group Los Muertos de Cristo. With friends, he rehearsed rock versions of the anarchist anthem: Son of the people, chains oppress you/and this injustice cannot continue, if your existence is a world of sorrows/rather than be a slave, prefer to die. Although he didn't go to school, he read constantly.

–How and when did you begin to identify as Mapuche?

–I was raised by my uncle Martiniano ( Jones Huala, Facundo's uncle ). He insisted on the flag and the kultrún (drum) . My identity was something that was there, I would wear the trarilonco but it didn't really make much sense to me.

Until she began to believe in the possibility of autonomy. And in 2013 she began to assert her Mapuche identity.

–At that time I had problems with alcohol; I felt an emptiness that I couldn't fill. I was going back and forth to Esquel until I stopped drinking when I began the process of my Mapuche identity. I started to see meaning there, something good to come.

Until then Matías had participated in support networks, but during those years he joined the Autonomous Mapuche Movement (MAP) of Puel Mapu, an organization of which he is no longer a part but to which he says he owes much of his political training.

–I had to learn. Basically, the points were land recovery, revitalizing trade, and liberating the Mapuche relationship with the land. My principles are land, justice, culture, and freedom. And they're not going to change here.

Around that time, he also met Luciana Jaramillo and Romina Rosas (two of the Mapuche women who had been evicted and arrested). They were already reclaiming land in Leleque, Paichil Antreao, Matías recalls. Paichil Antreao is a community that recognizes its pre-existence to the border between Argentina and Chile; they had been evicted in 2009 from the Villa La Angostura area (Neuquén). The reclamation of Leleque (Chubut) is a landmark event with many dimensions and marked a turning point, not only in Matías's life but also in the lives of the Mapuche people.

The Reconstruction of the Mapuche Nation

In March 2015, Matías began to wander through Cushamen, the area where most of his family was born, he recounts. Although he says he didn't participate in that dawn of March 13, 2015, when a group of families—among them many young people—crossed the fence surrounding the Compañía de Tierras Sud Argentina SA, part of the Benetton group. That gesture signaled that the Pu Lof community in resistance in the Cushamen department was part of a “Productive Territorial Recovery Process against the multinational Benetton, in the Leleque Ranguilhauo-Vuelta del Río sector.” The broader project: the Political-Philosophical Reconstruction of the Mapuche Nation. This was expressed in a Pu Lof Public Declaration, 03/13/15, their first document.

Behind the Mapuche families came the police, who attempted to evict them and fired weapons. The community resisted and reported the police actions to the courts. From then on, tensions escalated both on the land and within the justice system, which ordered several raids. The members of the community did not show their faces. In court, they were being labeled as terrorists and accused of land grabbing, cattle rustling, and weapons possession.

The land law, which Macri modified by decree in 2016, capped foreign ownership of rural land at 15%. Cushamen is one of the departments where this percentage has not been respected. In 2017, 19.45% of the land was owned by foreigners, according to figures from the RNTR (National Registry of Rural Lands).

In May 2016, the UN Special Rapporteur on Racism visited Argentina and spoke out about the Argentine government's repression of indigenous communities. “ The trend of repression reported in various parts of the country against the mobilization of indigenous groups to demand their rights, as well as the reprisals against minority rights defenders and leaders, and their family members, is alarming,” said Mutuma Ruteere.

In May 2016, Facundo Joanes Huala was arrested in a violent operation by the Gendarmerie . Facundo faced two charges: one for aggravated cattle rustling, accused of stealing livestock from the Benetton ranch (in provincial court), and another for an extradition request from Chile (federal court).

“The Mapuche with the binoculars”

2017 began violently in the Cushamen Lof resistance community. On January 10, the community was besieged by a massive operation involving 200 members of the Gendarmerie and the Chubut Provincial Police: a water cannon truck, cavalry from Trevelin, a helicopter, a water bomber plane, and drones were deployed to clear the tracks of a train that had been out of service for 15 years. With no judicial officials present, the community reported being subjected to mistreatment, racism, beatings, threats, and torture . The following day, the riot police injured two people, including Matías's cousin, Emilio, fracturing his jaw. Several people were arrested for resisting authority, but were acquitted years later.

–What was happening attracted a lot of young people. That year I met Santiago Maldonado.

We talked only when absolutely necessary. We discussed how to argue with the State. I'm more of an anarchist. Santiago said we were more communist. He had a strong personality.

-It felt like something was going to happen because of the way the repressive escalation was coming.

I remember the 31st, blocking the road. There was a lot of fog. When dawn broke, that fog was cold and damp. At 3 or 4 a.m., they tried to get in and opened fire on the road. The decision was made to continue the protest. They had repressed the protesters in Bariloche, and the decision was made to continue blocking the road. Today I see it as a youthful mistake, a lack of political training. It was important in 2015, but I think that after the Santiago Maldonado case, the political project began to crumble.

-You were a crucial witness in the Santiago Maldonado case.

I still maintain the same thing: I saw Santiago Maldonado being taken away by the Gendarmerie. And there is no evidence to the contrary.

–I haven't been able to read much about it. But sooner or later, the justice system has to seek the truth. I hope it serves as a lesson for all of us who were condemned socially and politically; truth and justice must go hand in hand. However, I don't think it will change much for those of us who are still fighting. Our people will continue to live under repression and imprisonment.

–Since 2017 they have been caricaturing you as the Mapuche with binoculars.

–I think it's to downplay it. I prefer to get to the heart of the matter: to talk about social inequality. They made up that I was prosecuted for perjury, which didn't happen.

–How did your activism continue?

–I campaigned for the MAP proposal. I've already distanced myself from the movement. Today I only support a few points. One grows up, becomes more politically active; there are things I don't disagree with, but these aren't the times. Today I don't want to be a lonko or anything like that. I want to be just another person, wherever I need to be. And any action against capitalism fills me with joy, even if it's not from my own community. I am a revolutionary activist for the cause.

–How do you feel about women's struggles?

"I support the struggle of women. Since you understand equality in its broadest sense, there has to be balance. My house is more of a matriarchy; there's no patriarchy there, and I don't want there to be. Taking care of things, cleaning the house, cooking—I do it all, and I can't afford to lose a fingernail. And that's precisely part of what I miss," she sighs and laughs.

Awaiting house arrest

Besides working and reading, in prison Matías gets up at 6 a.m., looks out the window to the east, and performs a Mapuche ceremony. He says that the activity, along with a spiritual and political dimension, helps him cope with confinement while he waits for house arrest so he can await trial in freedom.

–The worst part is the uncertainty. Because when you're condemned, you know how long you'll be there. Emotionally, for now, I'm doing well. I accept my political imprisonment with dignity; it's the fear of the oppressed speaking out. This imprisonment is a way to silence us. Meanwhile, I am deeply grateful for the solidarity I'm receiving from everyone who is supporting me. I represent not only the Mapuche people but also the poor who know what it's like to go hungry. I am a social activist. My enemy is the system, not even the State anymore. I don't ask anything of the State, least of all this government; they attack pensioners. I will die fighting for something just and true. That no one decides our lives and our freedom. I fight so that one day we can live better and more equally.

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.