New soldiers of gay fascism

The current rise in rejection of non-muscular bodies within the gay world is reminiscent of the brotherhood among men encouraged by the Nazi ranks, whose hatred of the feminine had an obvious racial component.

Share

Social media is a megalopolis of normative bodies. Especially Instagram. And especially the Instagram of gay users, whose feeds are a showcase of toned gym physiques shared in search of validation or, in other words, likes. Part of this quest for the “perfect” body is based on the notion that achieving it requires adopting healthy lifestyle habits such as systematic exercise and dietary control.

The public health discourse constructs “a disciplinary system of bodies based on mathematical precepts and indices developed from the 17th century to its culmination in the Nazi eugenics of the 1930s,” notes historian Tatiana Romero . Just as these precepts uphold the ideal of feminine beauty in thinness, even at the expense of physical and mental health, the masculine ideal demands muscularity. In her denunciation of fatphobia, Romero emphasizes the importance of focusing “on how attempts are made to control and discipline bodies so that they are not fat, and how, if they are, they must be materially eliminated.” Every ideal of beauty exerts its influence through mechanisms characteristic of totalitarian regimes.

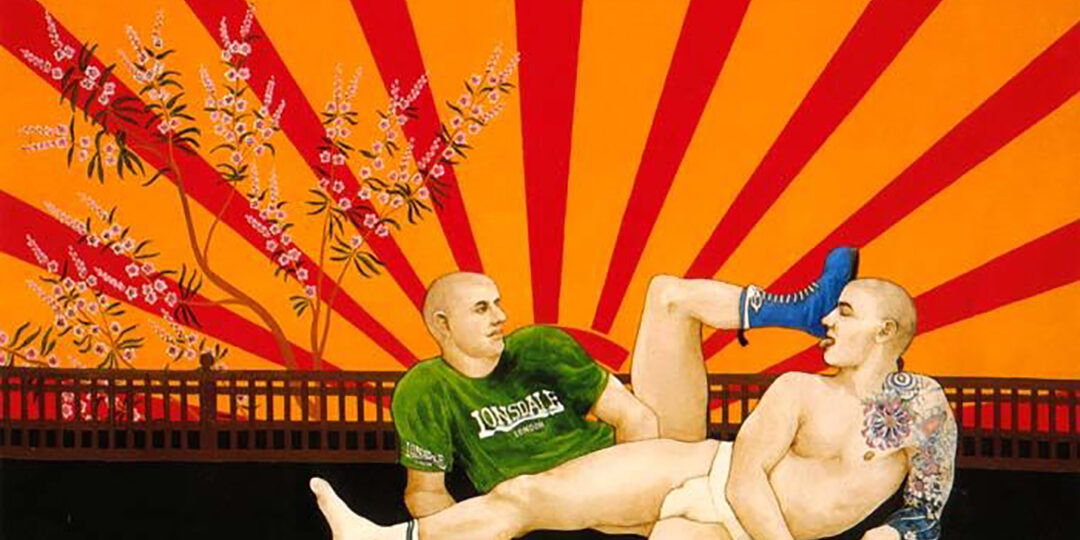

Professor of gender studies Jack Halberstam , author of *The Queer Art of Failure* (Egales, 2018), links fascism to male homosexuality because of its potential to “raise questions about the relationship between sex and politics, the erotics of history, and the ethics of complicity.” To illustrate his theoretical argument, Halberstam uses the work of two contemporary visual artists: the painter Attila Richard Lukacs and the photographer Collier Schorr . Both connect fascist imagery with homoeroticism to confront two systems of representation that, in principle, should be antagonistic. Regarding Lukacs's works such as *Love in Union * and * Adam and Steve* , he explains that they “create gay mythologies from fetishistic combinations of nationalism, violence, and sex, and allow pornography to compete with classical imagery.” This hypermasculine fetishism refers to the work of the visual artist Touko Laaksonen (1920-1991), known by the nickname Tom of Finland, which is usually interpreted as a liberating exaltation of male eros and leaves aside the possibility that said imaginary is not entirely revolutionary.

Attila Richard Lukacs, Love in Union – Amorous meeting (1992)

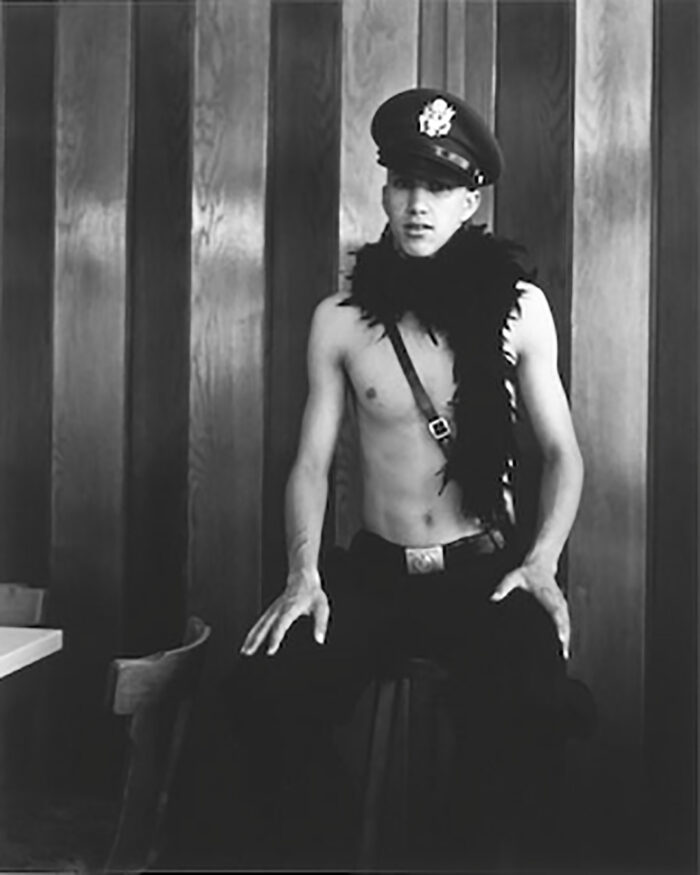

Collier Schorr 's art project , "Neue Soldaten" (New Soldiers, 1998), consists of photographic portraits of young men dressed as soldiers from various regiments, including the American, Israeli, and Nazi regiments. Halberstam explains that, "unlike Tom of Finland and skinheads , who share a reproduction of Nazi fetishism, Schorr's images acknowledge the clear sexual appeal of military imagery, but also capture the uncomfortable reality of that appeal." According to Schorr's discourse on his work, there is a strong connection between horror and eros that transforms Nazi imagery into a sexual fetish based on the allure of the forbidden and the dangerous.

This hypertrophied masculinity functioned, then and now, in opposition to the stylized femininity dictated by the binary conception of gender. However, what in the mid-20th century served as a way to redefine and reclaim elements of oppression seems to have partially recovered its reactionary origins today due to the exaltation of muscular men's bodies on social media and the denial and rejection of those who are not.

In 2015, Egyptian model Mina Gerges went viral thanks to the homemade recreations he shared on his Instagram account of looks from pop artists like Beyoncé and Rihanna . The fact that he was a made-up man from the Middle East who was completely comfortable in his own skin attracted so much online harassment that he was forced to temporarily deactivate his account. In an interview with Paper Magazine, he explained that he had grown up seeing images of unattainable men he wanted to emulate—mostly white and thin—and that these unrealistic expectations led him to develop an eating disorder. “ Gay men are taught to idealize fit, sculpted bodies because that’s the only body type we see on dating apps like Grindr […] This seeps into the kind of attitude people have when they write 'not fat, not effeminate' in their dating app bios, and it’s obvious when you see Instagais posting shirtless photos for their thousands of followers to idolize their bodies.”

Grindr creator Joel Simkhai , in an interview with The New York Times , described himself as a highly visual person and believes that image is what drives people to pursue their interests. He defended his app against criticism in this way. “Grindr got me in shape and made me go to the gym more often, giving me better abs,” he explained in the interview. “People criticize it for being superficial, but I didn't invent that aspect of human nature. What Grindr does is elevate your game.”

The creator of Grindr believes that image drives people to pursue their interests and acknowledges that the app helped him get in better shape.

Erotic Nazis

The spectacular aesthetic characteristic of fascism also exerted its influence on gay men in the past, at least those whose social standing shielded them from its dangers. One of them was the American architect Philip Johnson , known for bringing the International Style to New York after meeting Mies van der Rohe , director of the Bauhaus, during one of his visits to Berlin. During his travels to Germany, he dedicated himself to his architectural studies and also sought sexual experiences with men, becoming captivated by the spectacle of Nazi rallies filled with young men dressed in black leather—an erotic attraction that would soon be sublimated into a staunch defense of Nazi ideology. This is recounted by the writer and poet Gregory Woods in *Homintern: How LGBT Culture Liberated the Modern World* (Dos Bigotes, 2019), where he traces the influence that numerous LGBTQIA+ figures have had on Western culture from the 19th century to the present day. In his chapter “Flirting with Fascism,” he also points out that the Italian director Luchino Visconti , although he dedicated his career to fighting fascism in his country, was also drawn to the aesthetic aspect of Nazi parades. As he confided to a friend, “I had gazed with intense desire at the rows of uniformed, blond, sadistic young men.”

Apolitical?

It is now that the convergence of eroticism and fascism seems to occur in a completely superficial way, devoid of the political component to which it was linked in the mid-20th century. However, one could argue that denying the existence of this relationship would amount to a form of denialism. If before the concept of nation was venerated as a cult, now this fervent cult is concentrated on the body itself. The current rise in rejection within the gay community of men who refuse to conform to hegemonic masculinity and of non-muscular bodies is reminiscent of the brotherhood among men fostered by the Nazi ranks, whose hatred of the feminine had a clear racial undertone . The Aryan ideal of beauty championed by Hitler was based on physical strength, endurance, and virility—attributes exalted in the ancient world. Everything our fantasies associate with fascist imagery actually finds its origins much further back in time and in a much deeper abyss that serves as inspiration and genesis for both gay eroticism and fascism. The vision of the superman as a war-sexual artifact has its first manifestations in classical cultures. We are indebted to the cult of the male body that Greek artists expressed through sculpture, from the kouroi of Etruscan influence that depicted broad-shouldered youths—and, in some cases, a six-pack that rivals that of modern-day CrossFitters—to Polyclitus 's Doryphoros in the High Classical period—a prefiguration of the frat boy in teen movies—and one need only look at the Laocoön to connect it with the hypertrophied men of Tom of Finland.

Now it seems that the connection between eroticism and fascism is superficial, devoid of the political component.

In truth, the masculine ideal hasn't changed much, nor have the mechanisms for consolidating itself in the collective imagination. For a beauty ideal to take hold, public opinion must be based on a predetermined model. And that predetermined model must be opposed to an anti-ideal, a caricatured scapegoat from which one wishes to distance oneself. No one wants to suffer rejection from their peers. If that means having to collaborate with the tyranny—in this case, the tyranny of the body—it's a necessary evil to which it doesn't seem difficult to submit. In reality, thanks to the immediacy and accessibility that Instagram offers in disseminating this ideal, perhaps it's more accurate to say that the difficult thing would be not to submit to it. The ideal of male beauty has been domesticated; it has been democratized, which is an extraordinary paradox. It's everywhere, all the time, like an occupation. Naturally, and fortunately, resistance arises in every dictatorship. And the resistance to the cult of the body in the gay community is no exception.

This article was originally published in Pikara magazine.

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.