How does the Argentine justice system handle cases of transphobic murders?

The rulings in 8 transvesticide cases demonstrate that the justice system has made little progress in applying a gender perspective when investigating.

Share

This investigation examines court rulings that refer to trans women by their birth names, failing to acknowledge their vulnerable circumstances and ignoring their lives and relationships. It explores how the Argentine justice system discriminates against trans women when they are victims of crime, and why the role of organizations, friends, and family is crucial in explaining trans women's lives to the judicial system.

identified 54 cases of transphobic murders in the last six years, of which only 8 rulings due to the lack of systematization of the sentences. These judicial documents revealed serious biases and discrimination, as well as some judges who applied a gender perspective.

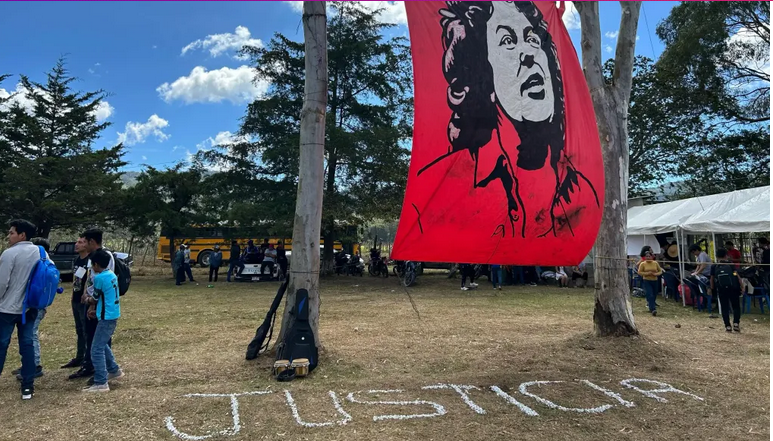

Illustration: Kenya Altuzar

“From a wide range of insults he could have uttered, the accused specifically chose those that referred to ER's trans femininity, which clearly reveals his transphobic personality biases.”.

Judge Marcela Alejandra Leiva in the ruling for the transvesticide of Evelyn Rojas.

17/03/2022

Evelyn Rojas was murdered on October 27, 2016, in the province of Misiones, Argentina. The trial for her death took place in 2022: six years later. A court had to decide whether Ramón Da Silva had killed her and whether he had done so out of hatred for her gender identity.

The first judge to vote decided that he had killed her, but not out of hatred, because the murderer was his partner. So, perhaps Dr. Viviana G. Cukla thought, how could he hate her?

But another judge, Dr. Marcela Alejandra Leiva, was also present in the courtroom, and she did consider Evelyn's murder a hate crime. During the sentencing, she said: “If the perspective of sexual minorities is not incorporated into judicial decision-making, we will continue to fail to achieve true equality.”

He continued: “It becomes mandatory for those of us who hold judicial positions to be aware of any type of stereotypes or prejudices based on gender in order to achieve adequate respect for the rights of historically vulnerable people (...)”.

In the same trial, Dr. Leiva asked the murderer:

—How did you find out about ER's death?

—I was told, by the other transvestite— replied Ramón Da Silva.

This research will explain, based on a survey of cases from the last six years and an analysis of court rulings , how the justice system treats transphobic murders : biases, discrimination, the use of deceased names by doctors and police, the dismissal of hatred based on gender identity , and also some glimmering insights from a gender perspective to continue exploring. The ruling in the Diana Sacayán transphobic murder case serves as a guiding light.

Gender-sensitive rulings

How many like Diana and Zoe in the last six years?

Since 2018, 54 trans women and transvestites have been murdered in Argentina . The number is surely much higher; it's difficult to know for sure.

There are official institutions and organizations that collect data, but they focus primarily on cases of cisgender women, such as the Women's Office (OM) of the Supreme Court of Justice of the Nation , Casa del Encuentro , the MuMaLá Observatory , the civil association Ahora que sí nos ven, and the Lucía Pérez Observatory . Therefore, the number of transphobic murders they report is much lower than the number collected for this investigation.

Until 2022, the members of Rosa Naranja , a civil association that advocates for the rights of transvestite/trans identities , compiled statistics on deaths in the context of transvesticide and social precarity. They did so for more than ten years. “Every time we had to do it, we got incredibly stressed. Because it's transvestite comrades who are dead, who have disappeared,” Marcela Tobaldi, an activist and leader of the organization, told this investigation.

“And since no one, absolutely no one, cares about these statistics, we as an organization decided we weren't going to work on this issue anymore. Because it devastated us, saddened us, filled us with anguish, and we had no answers,” she said.

Since there are no complete or exhaustive official records, this investigation involved a search of media outlets across the country, temporarily limiting the search to cases that occurred or were tried between 2018 and 2023. Articles were taken from mainstream media and cross-referenced with media specializing in LGBTQ+ issues . In addition, advanced Google searches were conducted using keywords that might contain gender bias in the news text.

This is how we came to count at least 54 murdered trans women and transvestites. The brutality of the crimes, the vulnerability of the victims, and the negligence of the authorities are recurring themes in every news report. This makes it even clearer why it was so difficult for the activists of Rosa Naranja to review and tally each case.

The ultimate goal of this survey was to identify the legal cases initiated following each murder, in order to analyze how the justice system handles cases of transphobic murders. However, this task proved more complex than anticipated.

Difficulty in accessing rulings: the justice system does not systematize

For this investigation, we submitted requests for access to public information to the Supreme Court of Justice of the Nation, and sent requests to the courts of all the provinces where we found that a trans or transvestite person in the last six years. We also made requests to the Public Prosecutor's Office and the Argentine Legal Information System .

Only the Specialized Prosecutor's Unit for Violence against Women (UFEM) and the Supreme Court of Justice had reports compiled from case rulings. The other institutions responded that it was nearly impossible to identify these rulings in their databases.

To delve deeper into these aspects, we requested, through a freedom of information request, that the Court provide the rulings mentioned in the report. The Women's Office of the country's highest judicial body responded that the National Registry of Femicides of the Argentine Justice System “is built with input from all jurisdictions in the country, through a case anonymization system, in which a code is used to track cases.” However, this Office “does not have direct access to the cases being processed throughout the country.”

And it recommended using the search engine with the case numbers. However, it was impossible to find the rulings because there is no field to enter that number. Therefore, we conclude that the highest court in Argentina does not systematize cases, nor does it have transparency policies for accessing judicial documents on transphobic murders .

The search was very complex because, moreover, there isn't a single criminal charge that appears on the case files. The murder may initially be investigated as an inquiry into the cause of death, then as simple homicide, or aggravated homicide. The initials of the murdered trans woman's name may appear, and they may even be the initials of her name after death.

“With the issue of registries, especially the justice system, which is more resistant, when a person hasn't legally changed their gender identity , they are registered with their birth certificate. It will be very difficult, or almost impossible, to obtain that information. When there's no change to the national identity document, the cover sheet shows the name assigned to the person at birth,” explained Florencia Guimaraes, former head of the Gender Observatory of the Buenos Aires City Council of Magistrates, activist, and member of the organization Furia Trava.

We began our search, consulting with more specialists, such as Dr. Carlos Garmendia, a lawyer from Tucumán, and Dr. Luciana Sánchez, a lawyer from the City of Buenos Aires. We found that, in cases of murder of a transvestite or trans person, three aggravating factors are typically considered, as outlined in Article 80 of the Argentine Penal Code. These are: subsection 4, which is a hate crime; subsection 11, due to gender-based violence ; and subsection 12, if the perpetrator has a relationship with the victim, aggravated by that relationship.

The sea of homicide cases is immense. One would have to read every single ruling, and even then some might go unrecorded, because if the identity of the murdered person isn't mentioned in the proceedings, there's no way to know if they were a trans woman or transvestite.

“If a robbery occurs, it will likely be classified as a crime committed to conceal another crime; or the charge will be that treachery is involved, or that other aggravating circumstances under Article 80 of the Penal Code will be applied. Except in very specific cases, the aggravating circumstance in subsection 4 (hate crime) does not usually appear as the first option. This is because, for many legal professionals, proving hate as a state of mind presents a difficulty,” explained criminal law specialist Javier Teodoro Álvarez for this investigation.

Finally, with the support of lawyers working on this issue and some provincial courts that responded to our requests, we obtained eight rulings. To these we added the sentences of Evelyn Rojas and Diana Sacayán , which were outside the timeframe of this investigation but are key to understanding the need to apply a gender perspective. We analyzed these ten documents in our own database and used the ruling on Diana's transphobic murder as a reference to see if it was being considered.

Ruling on the transphobic murder of Lourdes Anahí Reinoso. Highlighted where she is referred to by her deceased name.

Violence: a constant in every case of transvesticide

Fabiola Ramírez legally changed her gender on her identity document at age 18. At 22, she was beaten and suffocated to death.

Lourdes Anahí Reynoso requested a restraining order against her ex-boyfriend, Julio Paladini. Two months later, he went to her house, tied up, tortured, and murdered her aunt. He waited for six hours until Lourdes arrived home from work, punched her repeatedly, and stabbed her to death.

Mirna Di Marzo was leaving a nightclub in Salta when a man knocked her to the ground and kicked her in the head until she was in a vegetative state. She died three months later.

Gala Estefanía Perea met Víctor Martínez when she was 16 and he was 39. Her sister says he forced her into prostitution to pay the bills. Lourdes tried to report him once, but the police mocked her. They were together for four years until he suffocated her in the room they shared.

Melody Barrera was looking for clients one night in Guaymallén (Mendoza) when she got into an argument with police officer Darío Jesús Chaves Rubio. The officer told a Cabify driver that he was going to get a gun and “shoot him.” He returned and murdered her with six shots to the back.

Vicky Nieva dated Maximiliano Gutiérrez for five years. He had already tried to kill her by throwing gasoline on her. People in the neighborhood knew that Vicky suffered abuse at the hands of her partner. She managed to leave him, but Gutiérrez harassed her every day. Two months later, he killed her.

Thanks to the efforts and activism of the LGBTIQ+ community, we know about the vulnerable situation that transgender people face throughout their lives. The violence begins like a domino effect when families expel them from their homes; then they lose the opportunity to get an education, access healthcare, have a job, a home, or a partner who respects them. Transgender women in Argentina have a life expectancy of 40 years, while the average for cisgender people is 77.

But in addition to the structural violence of being denied basic rights and social discrimination, trans women and transvestites suffer a corrosive form of sexist violence , whether from strangers or their own partners.

Prosecutor Diana Goral, in the trial for the murder of Alejandra Salazar Villa, explained: “The type of sexual-affective approach between a man and a transvestite/trans person, that desire, contravenes a social and socio-affective order. Sometimes, due to the type of crime, the brutality with which they are committed, it could be understood that the person who kills a transvestite is trying to kill the desire for that person, because that person is considered abject, someone who breaks the patterns imposed by the sex/gender order.”

Argentina is a pioneer in Latin America regarding the rights of LGBTQ + : marriage equality, the Gender Identity Law, and the Transgender Employment Quota. It is also one of the first countries in Latin America to prosecute crimes against transgender people as hate crimes.

However, hate crimes present a trap: the requirement to prove that the aggressor hated the victim because of their gender identity. That they insulted them, that they acted with particular cruelty, that they exposed their body. Prosecutorial strategies focus on gruesome details and lose sight of the concrete fact that the trans/travesti population lives in a situation of constant vulnerability. That hate is societal.

For example, Judge Viviana Cukla, in her argument to dismiss the hate crime charge in the trial for the transvesticide of Evelyn Rojas, said: “We see that the prosecution based the existence of hate, mainly on the physical (kicks, blows) and verbal aggressions that Junior directed towards ER constantly, insults such as 'dirty faggot', 'transvestite', 'you're not even good for fucking', 'dick sucker'—, as well as on the degree of violence used to cause her death, the multiple blows to the face and other parts of the body, the clumps of hair cut, the exposure of the genitals as a sign of hate, among other elements of this nature.”

But he concluded: “However, these circumstances do not in themselves determine hatred —according to the requirements of art. 80 inc. 4— when other elements arise that contradict such a hypothesis, such as, one of them, the same relationship that Junior and ER maintained, a relationship that, beyond being traversed by very serious situations of violence, found a minimum stability of cohabitation and publicity.”

Discrimination in rulings: Use of dead name

We found that in half of the rulings analyzed, the use of Article 80, paragraph 4, to classify the homicide was dismissed. Furthermore, in four rulings, the deceased victim's name was used in various testimonies: in one, even from the murderer himself, who was the victim's partner. In others, it was used by doctors, police officers, and family members.

In the case of Gala Estefanía Perea, for example, the prosecutor argues that it was not a hate crime and speaks of Gala's physical build because she was born with male genitalia: "From my point of view, I do not find that the act was committed with hatred or gender violence […] it is also stated that she weighed 75 kg, and was 1.70 meters tall, consequently she retained all the characteristics of a robust man."

Discriminatory rulings

In the ruling for the transvesticide of Lourdes Reinoso, her name was used in three instances: in the testimony of the murderer's cousin: "...I approached that room, which was the bathroom, and I saw that the two of them, that is, my cousin and Pedro (Lourdes), were lying face up next to each other"; the police also wrote in the intervention report: "after this they left through the back of the property where they found another victim 'of the male sex'"; and in the autopsy, the doctor wrote: "Lourdes Reinoso (Pedro Reinoso) died from hypovolemic shock due to a stab wound."

LGBTIQ+ organizations and family members explain the transvestite life to the justice system

One day, Javier Teodoro Álvarez, a criminal law specialist and member of the organization Diversity and Rights, was told by a prosecutor that he didn't understand the word "chongo." The term would later prove crucial in determining the sentence for the murder of a transgender person.

“In one case, a prosecutor told me he had to decode the term 'chongo' because many witnesses were referring to the accused in a homicide case against a trans person as 'chongo,' and he didn't understand whether or not it was a stable, committed relationship that could impact the aggravating circumstances of Article 80 (particularly subsection 1). This explanation was provided by the LGBTIQ+ organizations that approached him. This happens frequently; in the vast majority of cases, it's the organizations that act as a bridge and try to compensate for the lack of specific training.”

According to the specialist, “there are judicial practices in Argentina that obstruct access to justice for transvestite and trans people,” and for this reason he highlighted the importance of organizations and friendships in judicial processes: “A large majority of judicial operators are unaware of certain particularities of the reality of the community,” he added.

With friendships, he said, the same thing happens: “Even today, in 2023, there are many people who hide their sexuality from their families, who know absolutely nothing about their friendships, social circles, etc. That is where friendships try to fill that void.”

The legal precedent: ruling in the transvesticide case of Diana Sacayán

The Diana Sacayán case set a precedent in the Argentine justice system. Before 2015, before this trial, hate crimes had never been considered an aggravating circumstance. Although the term "transvesticide" was not used in the subsequent rulings analyzed, the court's decision in that case—applying a gender perspective—was cited as an example.

In the case of Alejandra “La Power” Benítez, 34, who was violently murdered in Tucumán, the prosecutor highlights that Diana Sacayán's ruling was a beacon for trials in cases of transvesticide: “A landmark case in our country and a landmark case throughout the region, which has earned the recognition of the IACHR (Inter-American Court of Human Rights), basing its ruling on good practices.”

Despite the prosecution's arguments, the Tucumán court initially acquitted the defendant. The case reached the Tucumán Supreme Court thanks to appeals from the plaintiffs and the prosecutor, who again cited the Sacayán ruling. The Court determined that a retrial was necessary, but this has not yet taken place, even though the crime occurred in November 2020.

The case of Melody Barrera was the first in which the Supreme Court of Justice of Mendoza ruled on a transphobic murder as a hate crime. “Judicial officers, as well as members of juries, have been socialized within a patriarchal system that has led to the normalization of these practices. The State and its agents have the responsibility to incorporate a gender perspective into all their actions,” said one of the judges in the case, Omar Palermo, in the ruling. In that case, the murderer was sentenced to life imprisonment.

This work was carried out as part of the first "Data to View Other Narratives" call for proposals, an initiative by @Datacritica to tell stories about gender and sexual diversity from an intersectional perspective. The call was made possible thanks to the support of Numun Fund.

Data Crítica is a data journalism organization with a Latin American focus. We investigate, generate, and share knowledge to strengthen critical narratives about inequalities, using data analysis and visualization. Our thematic areas are gender, climate justice, and the struggles of the Americas.

Credits

Edited by: Naomi Morato and Patricia Curiel / Data Crítica

Data analysis and visualization: Fer Aguirre / Data Crítica | Verónica Liso and Rosario Marina

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.