Blanqui García, the fisherwoman who, along with her community, recovered an endangered mangrove

The Metalío mangrove in El Salvador was in danger. Until a community group, led by environmentalist Blanqui García, organized to revitalize it, reforest it, and implement mitigation measures. This mangrove forest protects biodiversity and provides a source of income.

Share

Blanqui García and her partner, Juan Alas, usually get up at 4:00 a.m. to go to Metalío Beach, which is a five-minute walk from their house. She is a small-scale fisherwoman. Before leaving, she prepares food to sustain them during the day they will spend at sea. She packs her fishing gear in a backpack: nets, ropes, anchors, and a cooler. They pull the boat's tank and motor from the house to the beach, which is part of the Acajutla district.

Upon arrival, Blanqui and Juan get everything ready on the boat to begin their workday. They spend several hours at sea. At the end, they return home with 40 or 20 pounds of fish, depending on the quality of the catch. If it's early, Blanqui walks through the main streets of the community offering the fresh fish. If not, he waits until the next day to sell them. The fishing trips are long, sometimes nine hours, other times more than twenty.

When Blanqui learned to fish, she was eight years old. Her father, Don Israel, would take her to the mangrove near their house after school. There he taught her traditional fishing techniques, how to use a cast net, and how to choose the best spots to catch the most fish and scraps. Her mother, Teresa de Jesús, sold the catch in the surrounding areas of Metalío. Since then, Blanqui has dedicated herself to fishing.

She was born and raised in Metalío. At 32, she is a fisherwoman, environmental activist, and leader in this community, located a few meters from Metalío beach and 8 kilometers from the port of Acajutla, in the department of Sonsonate. It is home to around 250 families. Most of them work primarily in fishing, agriculture, and paid and unpaid domestic work. She is also a key figure in the recovery of the Metalío mangrove.

How does the community depend on the mangrove for its livelihood?

For the community of Metalío, this mangrove is more than just submerged branches in mud: this coastal forest is a vital part of their livelihood. It's a source of income, but also of food. Every day, several people who make their living from artisanal fishing dive into the mangrove's salty waters to catch fish and shellfish, which they then sell. This is how they ensure their economic sustenance.

According to the 2022 Multiple Purpose Household Survey, 7.2% of El Salvador's population works in the agriculture, livestock, and fishing sectors. Of those employed in these sectors, 11.2% are men and 1.7% are women. The survey also reveals that income for these occupations ranges from $291.14 to $337.83.

Blanqui frequently visits the mangrove forest located just a few meters from his house. He knows its 191 hectares very well. He knows where to find the most fish, the birds that visit, and even the specific locations of the crocodiles. Of the 191 hectares that make up the mangrove forest, 165 correspond to the estuary and mangrove area, and 26 to the marine area.

In our country, mangroves are ecological reserves and considered fragile areas, which is why Article 74 of the Environmental Law stipulates that "no alteration of any kind shall be permitted within them." Furthermore, this law recognizes that these ecosystems are among the most prominent and productive in the world and that they support a great diversity of species. According to the UN , they play a vital role in the health of the planet. They act as natural buffers against storms and tsunamis, protecting coastal communities from disasters. They have the capacity to store large quantities of carbon dioxide, which contributes to mitigating climate change. In addition, they serve as breeding grounds and refuges for a diversity of animal species.

According to El Salvador's National Wetlands Inventory , this mangrove forest is home to an incredible diversity of species, including shrimp, fish, mollusks, and shellfish. It also serves as a habitat for mammals such as raccoons and a refuge for migratory birds. This coastal forest is also part of a Ramsar site, an area designated for the conservation and sustainable use of wetlands of international importance. These sites are recognized by the Ministry of the Environment as ecosystems of ecological value and are protected to maintain biodiversity.

In 2013, the Metalío mangrove was dying. Deforestation and pollution had devastated the habitat. The former was the result of indiscriminate logging, unsustainable agricultural, fishing, and livestock practices, and the construction of urban and tourist infrastructure. The latter was due to water pollution from plastics and agrochemical waste. These, explained Marcela Díaz, a biologist with the Salvadoran Ecological Unit (UNES), are the main factors harming these coastal forests.

The community itself was aware of the poor condition of the mangrove. The absence of mangrove trees was noticeable, as was the decline in species such as catfish and fish.

The report from the forum "Advances in the conservation and inclusive restoration of mangroves, adaptation strategies to climate change" of the Ministry of Environment in 2012, indicates that "El Salvador has lost 60% of its cover since 1950, going from 10,000 to about 40,000 today."

In addition, a study by the World Mangrove Partnership indicates that over 60% of mangrove degradation is a result of human activity, including agriculture, aquaculture, and urbanization. The remaining causes are attributed to natural factors such as erosion, sea-level rise, and storms, all exacerbated by climate change.

Collect seeds to reforest the mangrove

Every six months, a group of more than twenty people gathers at Blanqui's house. They usually meet at 8:00 am to share breakfast together. On the morning of September 13, 2023, while enjoying beans, cheese, and French bread, they discuss the rising cost of basic goods, how their fishing trip went the day before, and the availability of boots for entering the mangroves.

Some people are wearing rubber boots, although others prefer to go barefoot or in regular shoes. The clock reads 9:30 a.m. They are already half an hour late. The plan was to leave at 9:00 a.m. Blanqui decides that, to avoid the high temperatures, they should start harvesting as soon as possible. They prepare buckets, sacks, and crates where they will store the collected seeds.

More than 10 years ago, the community began to recognize the importance of the mangrove. They started collecting seeds for reforestation, created a tree nursery, monitor the mangrove's physical, chemical, and biological parameters monthly, conduct clean-up campaigns, and give awareness talks. They address topics such as the impact of pesticide runoff on fish and how deforestation reduces oxygen levels. All of this is done to mitigate and counteract the harmful effects of factors that affect the health of this ecosystem.

The seed collection they will undertake this morning is part of the restoration efforts in this mangrove forest in Metalío. They will collect four types of seeds, including candelilla seeds, also known as red mangrove, white mangrove, black mangrove, or istaten; and buttonwood seeds.

It's 9:45 a.m. In small groups, they walk about a kilometer to reach the area. It's near Blanqui's house. The children run around, and the dogs join them on the trek. As soon as they enter the mangrove, they identify the candelilla and button flowers to collect them in sacks or crates. The terrain is difficult, and their boots grip the muddy ground firmly.

After two hours, and having collected enough seeds, the group returns to Blanqui's house, where the nursery is located. Everyone plants the seeds in small plastic bags. While they work, another group of six women prepares lunch, which they will distribute at the end of this first day.

Blanqui mentions that this work takes a total of 15 to 30 days. In these almost three weeks, they will be able to plant more than 5,000 seedlings in the nursery. Six months later, when the mangroves are at their peak growth, they return to the mangrove forest to transplant them. According to Marcela Díaz, a technician with UNES, this effort has allowed the community to restore approximately 2.5 hectares of the areas identified over the past 10 years, leaving 1.5 hectares still to be restored.

Those who witnessed the mangrove dying say the difference has been noticeable and that these activities have improved the health of this mangrove forest.

"There weren't any trees here before. You could walk all the way to the other side and find nothing. Look at this beauty today! You go into the mangrove forest and it's so fresh, full of trees. Do you think we're not going to be happy to see this? Especially since we learned about their importance for oxygen. That's why I tell you to be careful about cutting down the trees," Teresa de Jesús describes while arranging mangrove seeds in a crate.

Marcela Díaz, a technician at UNES, emphasizes the importance of restoration efforts in the recovery of mangroves to counteract the impact of global warming. "An increase in temperatures and salinity, and a decrease in oxygen levels, have been observed. Restoration aims to address these changes so that the species affected by the inhospitable environment can thrive again in more favorable conditions."

In addition to carrying out these restoration efforts, people monitor the mangrove to prevent other community members from cutting down the trees. Marcela explains that these trees are exploited for firewood, as they tend to be long-lasting due to their salinity.

"One day some neighbors were trying to cut down some sticks for firewood. I told them not to do that. I explained that it has taken us a lot of effort to recover this land, and we don't want them just coming to cut it down. They all left grumbling angrily," says Teresa de Jesús.

"There's nothing to recover here."«

Blanqui, a central figure in this operation and whose home houses a mangrove nursery, didn't always share the conviction for the environmental struggle. Her mother, Teresa de Jesús, was one of the pioneers among the women of Metalío who committed themselves to restorative actions in the mangrove. Initially, Blanqui considered these activities a waste of time, reserved for those she perceived as people "without a job." She disagreed with her mother's activism.

Despite the pessimism and questioning from some people in her community, Teresa de Jesús decided to bet on an initiative that promised to preserve the mangrove, a source of life, work and food for her community.

“We saw the need in the mangrove. We went into that area and there were no trees, it was desolate,” she explains. Faced with this, she and Antonio, a man from the neighboring community of El Monzón, mobilized to seek help from environmental professionals to recover their mangrove. “We called the local forestry officials and they told us clearly that there was nothing left to recover, that everything was lost. But we didn’t stop there; we found ways to bring in media outlets to expose the situation,” she adds.

Later, some non-governmental organizations like Equipo Maíz and UNES arrived in the area to provide environmental training and information on actions that could be implemented in the mangrove. "I loved it. If I can support the environment and leave a legacy for my grandchildren, then I'll do it," says Teresa de Jesús when she recalls those times.

Her motivation to contribute to the environmental struggle also led to her being subjected to violence by neighbors and even family members. She was insulted and even called crazy for attending the training sessions. But this didn't stop her. She says that not even thunderstorms prevented her from attending the meetings.

Marine biologist Fátima Romero explains that one of the factors affecting fish reproduction and food availability is rising water temperatures, which disrupt marine ecosystems. This climate imbalance, she explains, poses a threat to aquatic biodiversity and global food security.

Blanqui kept his distance until he noticed the absence of fish and hooks while fishing. His catch plummeted from 60 pounds to just 40. However, he's also aware that this is an uphill battle. Although mitigation measures exist and much of the community has become involved in improving the conditions of this mangrove forest, actions that harm the health of this ecosystem, such as pollution and deforestation by other people in the area, still persist.

Today, it remains under surveillance and learning about how to continue preserving the mangrove.

One month after collecting the seeds in the Metalío mangrove, Blanqui, together with the people of the community, will continue to carry out other actions such as monitoring the physicochemical parameters of surface water, which seeks to measure the pH, temperature, salinity, conductivity and depth of the mangrove, in order to later plan and carry out mitigation works.

Mangroves are ecosystems that need saltwater to grow and are interspersed with the freshwater of rivers and streams that flow into the sea. This balance is essential for the survival of this coastal forest.

In six months, they will carry out a dredging of the canals, a technique that involves cleaning logs, organic matter, and sediment to restore water flow and increase the circulation of salt and fresh water, creating a balance for the well-being of the animals and plants that inhabit this area. In January 2024, the seeds had grown sufficiently and were planted within the Metalío salt forest, in a joint collaboration with UNES.

Government projects worsen the crisis

In addition to suffering the impacts of the climate crisis and unsustainable practices, mangroves in El Salvador face the additional threat of the construction of megaprojects in coastal areas.

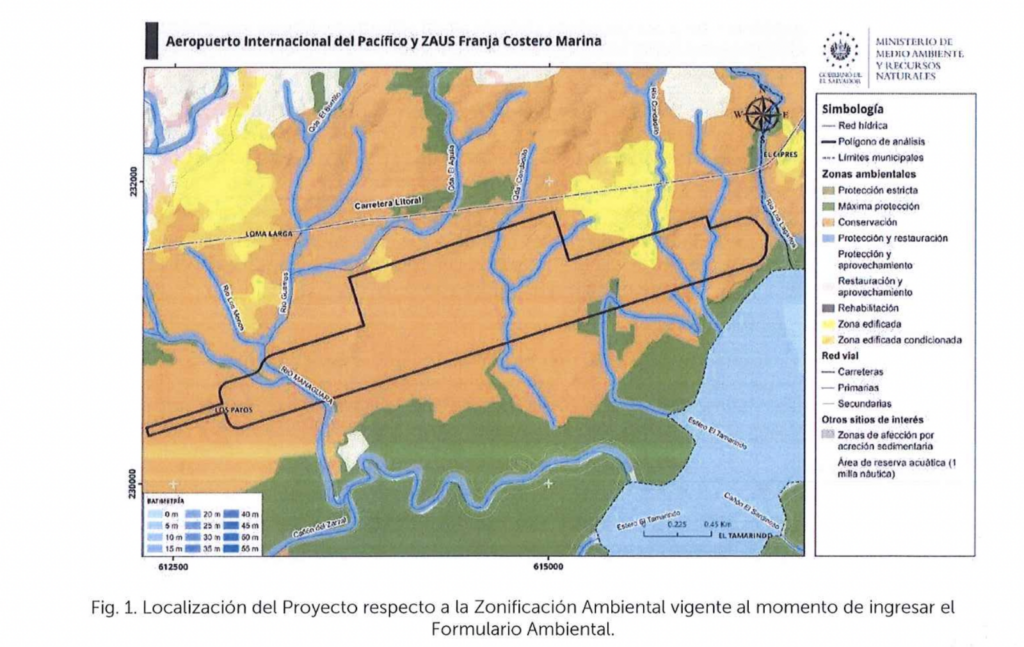

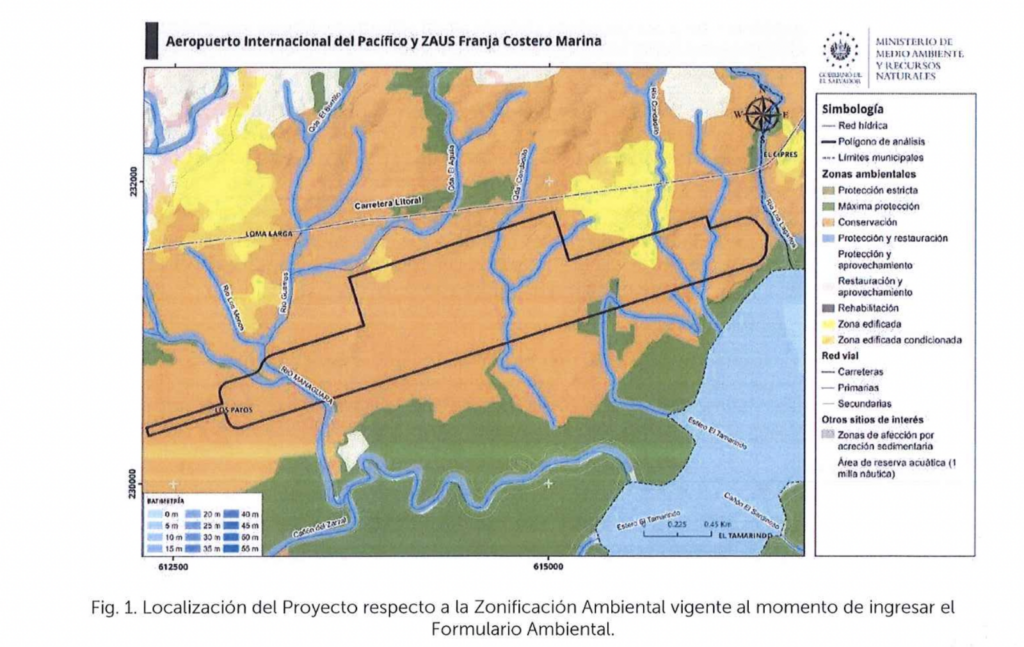

During the 2019 election campaign, the now president Nayib Bukele promised to build the "Pacific Airport" in the eastern part of the country, which is part of the conglomerate of projects under the so-called "Cuscatlán Plan".

This airport will be built in the Loma Larga canton, in the district of La Unión. It will have six boarding bridges to serve 80,000 passengers, according to a statement from the President's office.

Its location overlaps with a "small portion" of the El Tamarindo mangrove, according to a resolution from the Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources (MARN) dated October 14, 2021. According to MARN's 2018 National Wetlands Inventory , this mangrove forest covers 1,619 hectares and "is included in the National System of Natural Protected Areas (SANP) within the Gulf of Fonseca Conservation Area, but it lacks a protection decree, a management plan, and any conservation efforts." Furthermore, the resolution highlights that, despite the influx of communities and vacation homes, it has remained largely for the past 47 years.

Until 2021, the Guidelines for Environmental Zoning and Land Use of the Marine Coastal Strip, approved under the mandate of the then Minister of Environment and Natural Resources, Lina Pohl, and in effect since 2018, classified mangroves as "strictly protected zones." This implies, according to the document, "conserving biological diversity, ensuring the functioning of essential ecological processes, and guaranteeing the perpetuity of natural systems through sustainable management for the benefit of the country's inhabitants."

The guidelines "are a set of rules or guidelines that constitute legal and technical instruments that guide intervention in the territory for the purposes of protecting, conserving, and restoring the environment, as well as its sustainable use." These are based on Article 50 of the Environmental Law.

However, these guidelines changed in 2021 at the request of the current Minister of the Environment, Fernando López, who, via email, sent a proposed amendment to the Regulatory Improvement Agency on July 23, 2021. This agency is responsible for “improving regulations and simplifying procedures in public institutions so as not to negatively impact the business climate, competitiveness, trade, and the attraction of investors.” These regulations were renamed “Guidelines for Environmental Zoning and Land Use in the La Unión – Gulf of Fonseca Unit.”

According to the request submitted by the minister, the purpose of the new guidelines is to facilitate economic and social development in the territory of La Unión and the Gulf of Fonseca, without compromising the sustainability of local ecosystems. Furthermore, it is noted that the previous guidelines lacked precision regarding land use, which could result in environmental degradation of the area's ecosystems and hinder crucial state investments, such as the Eastern Pacific International Airport.

The changes to the guidelines from 2018 to 2021 involve the elimination of three categories: "Conservation," "Protection and Use," and "Restoration and Use." In their place, six new categories are added: "Conditional Protection and Use," "Aquatic Protection and Use," "Conditional Use," "Island Buildings," and "Areas of Special Interest."

In the 2021 guidelines, the action guidelines, which establish standards for environmental protection and ensure that activities and projects do not compromise the sustainability of local ecosystems, have been made more flexible. Within the "Strict Protection" category, which includes protected natural areas, as well as marine and coastal forest ecosystems, the construction of infrastructure for water resource management and energy generation and distribution facilities has been permitted with restrictions. In contrast, the 2018 guidelines, in the same category, authorized ecotourism.

"It is worrying that the Minister of the Environment, whose function is the conservation and protection of the environment and compliance with the Environmental Law, is changing this classification that already exists in the place and changing it to allow other types of projects, impacting the areas and the communities that depend on them," argues Luis González, a technician from UNES.

In addition to this, under the 2018 guidelines, the area delimited by the construction of the airport falls under the following land uses: Conservation, Built-up area, Conditioned built-up area, Protection and restoration, Maximum protection and Strict protection.

The construction crosses a portion of the El Tamarindo Mangrove, which is part of a group of mangroves protected according to art. 74 of the Environmental Law.

According to the resolution issued by the Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources (MARN) in 2021, this area serves as a transit and temporary nesting corridor for resident and migratory bird species heading towards the adjacent estuary areas, especially during the dry season. It also harbors local resident species considered threatened or endangered. The resolution also emphasizes the importance of considering this situation when evaluating the operational phase of the project, given the potential impact on airport operations and the risks associated with "accidental collisions between aircraft and birds."

In that same resolution, the Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources (MARN) mentions that this project meets the minimum requirement established for the Moderate or High Potential Environmental Impact (PIAMA) category. According to the 2017 Categorization of Activities, Works, or Projects , PIAMA includes "those activities, works, or projects that generate moderate or high potential environmental impacts; that is, those whose potential impacts on the environment are extensive, permanent, irreversible, cumulative, and synergistic, and which must determine respective environmental measures to prevent, mitigate, and compensate for them, as appropriate."

According to Luis González, measures to compensate for or mitigate damage in protected areas should not be considered; ideally, no work or project that entails an environmental impact should be undertaken.

An interview was repeatedly requested with Minister Fernando López and with José Alejandro Machuca Laínez, the Environmental Planning Manager of the General Directorate of Environmental Assessment and Compliance at the Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources (MARN). The objective was to address the modification of the Guidelines for Environmental Zoning and Land Use in the La Unión Unit, as well as its environmental impact on the La Unión area due to the construction of the Pacific Airport. As of the time of publication, no response has been received.

On April 26, 2022, pro-government and allied deputies in the Legislative Assembly approved, with 67 votes in favor, the "Law for the Construction, Administration, Operation and Maintenance of the Pacific International Airport," which, in its article 9, defines that "the Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources and the National Registry Center, among other public entities, are empowered to issue special guidelines that facilitate the issuance of documents and allow the granting of construction and operating permits related to the Airport, in an expedited and agile manner. These guidelines will determine the requirements that interested parties must present for the application of the permits, as well as the simplified administrative procedure to be followed."

The government, as part of President Nayib Bukele's campaign promise, is building the Pacific International Airport on land acquired by ISTA and transferred directly to CEPA, without the knowledge of its occupants, according to an investigation by Revista Factum. “The Project That Lands Through Deception in La Unión” exposes a case of property transfer without the owners' consent.

While the Ministry of the Environment ignores these environmental problems, communities are mobilizing to revitalize their livelihoods. The community of Metalío is a prime example. Their efforts to restore their mangrove forest have led many people to become involved in the environmental struggle and recognize the importance of living in healthy environments.

This article is published as part of an agreement between Presentes and Alharaca , an allied media outlet in El Salvador where this investigation was originally published.

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.