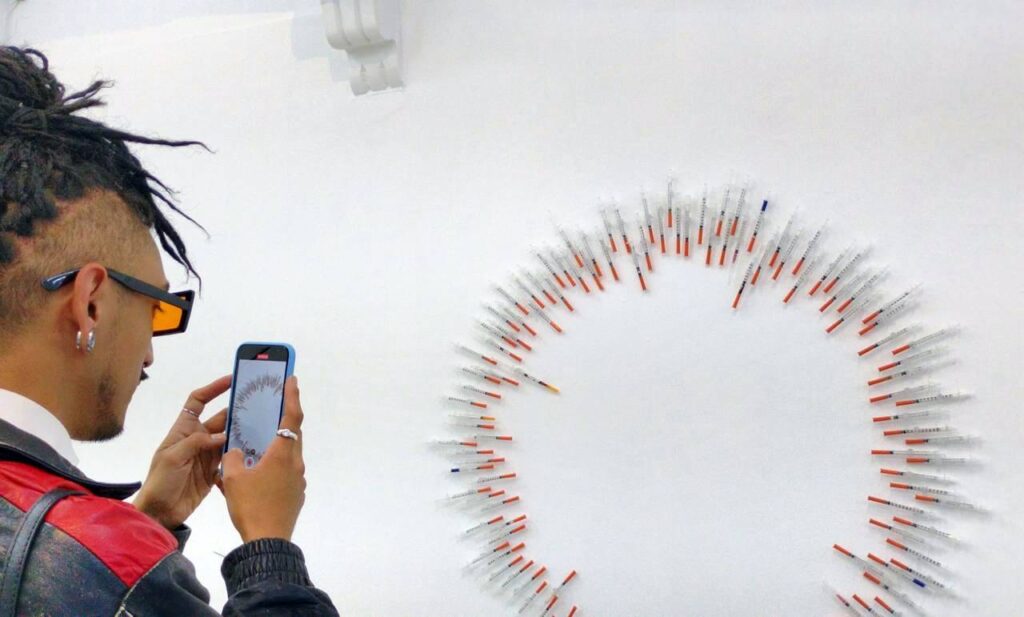

Mexico: A work by Valerio Gámez addresses the relationship between chemsex, spirituality, and pleasure

The artist seeks to engage in empathetic dialogue, based on his own experience, about substance use among gay men.

Share

MEXICO CITY, Mexico. — about crystal meth use, chemsex , spirituality, and pleasure.

Gámez's most iconic work is El Guadalupapi, a photograph in which a young gay man poses as the Virgin of Guadalupe. Today, it is one of the most well-known pieces in the gay collective imagination. It is displayed in one of the most iconic bars in the city's historic center, where the phrase "In this home, we pray with devotion to Guadalupapi" is displayed, mimicking the "This home is Guadalupano" message that Catholic homes in Mexico announce on their windows or doors.

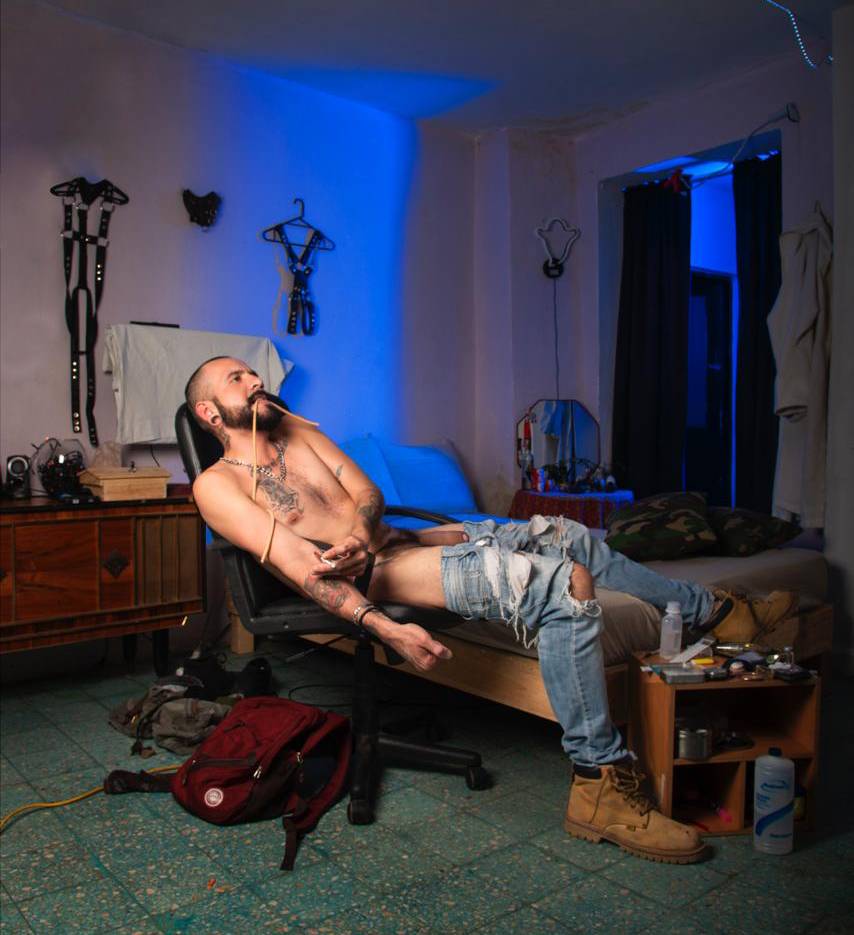

Valerio's work has been inspired by many themes. He draws primarily on religion and identity, from a cultural perspective but also on sexual orientation. In particular, he speaks to his peers, gay men. But his latest work also explores his own crystal meth addiction and the sexual practices he engaged in as a result.

What is chemsex?

Methamphetamines, such as crystal meth, are substances that stimulate the central nervous system and are currently the most widely used drug worldwide. According to the World Drug Report 2023 , 45% of the world's drug users consume this type of drug.

Among gay men, bisexual men, and men who have sex with men, the use of these substances and sexual practices has become more widespread in recent years and is known as chemsex.

"Amor de Cristal" journalist Rafael Cabrera explores chemsex in Mexico City. He recounts how these practices within the gay community generate dynamics not only of consumption but also of "pleasure, fetishism, and emotional connection." Another report by Altavoz LGBT explains the same phenomenon, but in the border city of Ciudad Juárez.

In first person

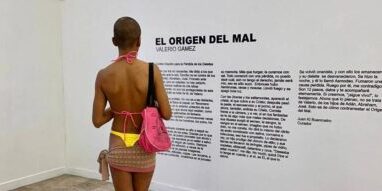

Presentes spoke with Valerio Gámez about his work and his most recent exhibition, “The Origin of Evil,” which will be open until February 29 at the ArtSpace in Mexico City.

-Why is the religious theme a central part of your artistic work and in your exhibition The Origin of Evil?

In this particular exhibition, the religious element is contrasted with sexual activity, but a sexual activity marred by the experience of crystal meth use. For me, it was once again a matter of discerning where the filters of value judgment, ethical and moral judgments, had gone regarding a sexuality deemed sinful, permeated by crystal meth addiction. In some way, this had destabilized my personal harmony. So, it is through these religious elements—Christs with tattooed phrases—that I seek a scapegoat to say, "No. This one is not to blame," to remove the burden of guilt for the addiction to sex, to substances. And also to the environments and people I encountered during my addiction.

And now I can reflect on it more and explain it better. I think religion is a normal reaction to the environment in which I grew up. In Querétaro, the atmosphere is very religious, very conservative, as in the rest of the country. But in Querétaro, it has a particular weight and permeates the culture and all aspects of daily life, social life.

For me, it's about deconstructing and questioning it, always from my personal experience, trying to explain to myself what this religious knowledge I felt and possessed was all about. It has always been a first-person reflection on where I come from, how much Catholic culture has permeated me, how much I've consciously acknowledged it, and how I react to it.

-Why talk about chemsex and from what perspective does your art seek to engage in dialogue about these practices?

Looking back now, the consumer phase and these pieces are from 2019. I was going through that when I started creating, and once I was able to move beyond that stage, I can reflect on certain things. One of them, perhaps the most important for me, is that these pieces and this exhibition are not an endorsement of consumerism, nor are they a condemnation. But neither are they a justification of consumerism.

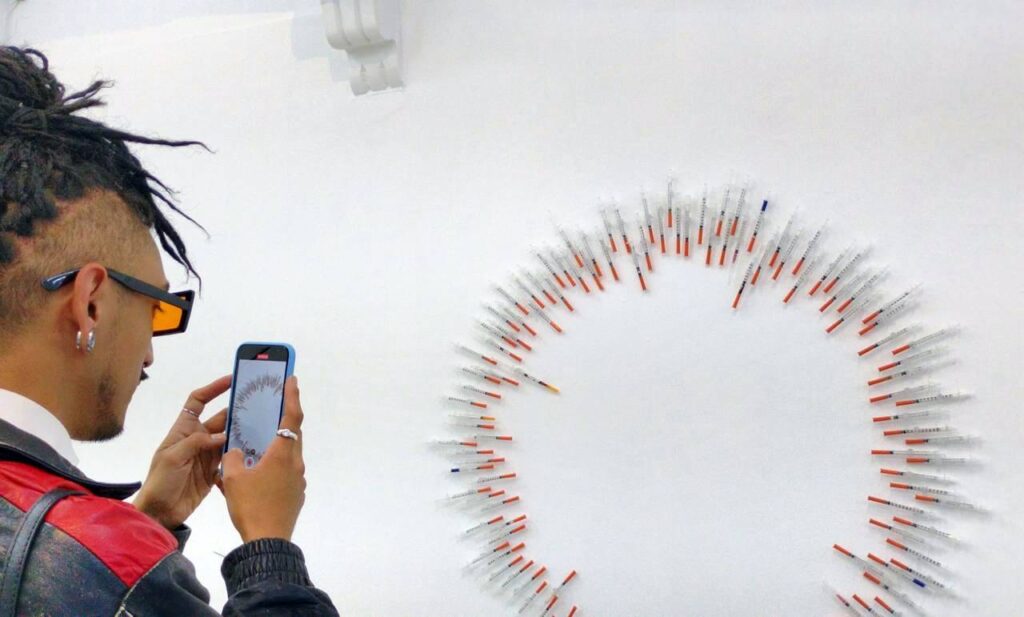

The intention of these pieces is to bring the issue to the forefront, not in terms of scientific or technical data, but to present it from an emotional and contextualized perspective. Doing this, in particular, helped me understand that what I was going through was also experienced by other people in relation to substance use and addiction; and that, for me, has been a stimulating experience.

Consumption, like any other human activity, has all its nuances, and addiction has all its nuances. So, for me, it was important to present the emotional elements, which I believe people can share experiences on and which can offer some guidance. And… and I'll say this too, a little light.

These pieces come from a dark period in my life. By saying this, I'm not stigmatizing either the sexual activity I had for many years or my crystal meth use. Quite the opposite; for me, it's about speaking frankly to my community, to gay men, that this happened to me, that I developed a crystal meth addiction. And these pieces don't just speak about me; they also speak about people close to me at that time. Some of them didn't make it.

-Chemsex has been closely linked to the gay population, what conversations need to be having regarding these practices both within and outside this community?

I think that fortunately, people who don't use drugs are starting to have different, less prejudiced perspectives. But prejudice about these practices is also deeply ingrained in the community, and I can say that from my own experience. Because I, too, before developing the addiction, had prejudices about it, not only about crystal meth, but also about the sexual practices involved.

I think it's very important to get rid of the idea that "if someone uses drugs, it's because they wanted to, and if someone develops an addiction, it's because they wanted to." We need to listen to the stories and understand the environments that lead people to develop addictions. I believe that speaking honestly about this experience builds bridges of communication, and these pieces aim to do just that.

Realizing my own prejudices before becoming a consumer, and then through living that experience, I realize that it's not just about talking to the gay community, but that we as a society should openly talk about sexual practices and addictions without prejudice.

-How have you felt about the reception of your work, what comments do people make about it?

I think it's helping to openly discuss, yes, drug use, yes, sexual practices, but above all, what people have told me is how it has impacted them emotionally. People who lost partners to addiction, family members who lost a child to the same thing, I had a friend who went through this, and so on. And that far surpasses anything I could have imagined.

I'm amazed by what art can achieve through the communication it fosters. I insist, although I'm not a health specialist, this work provokes conversation. It's true that developing an addiction always involves an emotional component. You can try a substance and not become addicted, but you might be going through depression and feel that it solves all your problems, leading to a dependency.

In that sense, it's been very rewarding for me because even back then, talking to fellow users about their emotional problems or issues related to crystal meth use was difficult; it's a taboo subject. It's easier to talk about having sex with lots of people, but nobody's going to talk to you about the emotional side of things.

I never imagined the response the book has received. It's generated a lot of interest, but above all, a deep connection and empathy. This has also given me a sense of certainty that this conversation was necessary and relevant. And I repeat, the topic is taboo while you're using; only when you stop using can you bring up the subject of addiction, and then you realize that there were other people going through the same thing. It's a personal experience, but also a very important and devastating one is what happens around you—in your circle of friends, partners, and family.

– In Mexico there are no public health policies developed for a community as specific as the gay population. Based on your experience, what is needed from the State to address this issue without stigma and without creating forms of consumption that put those who engage in these practices at greater risk?

"It's a complex issue. I use public health services, including the psychological therapy that helped me overcome addiction; but I think there's clearly a lack of focus on the gay community and their health. And above all, I'd say that, at a societal level, there need to be institutional mechanisms in place to care for our mental health, providing mental health tools and resources for personal development, while also understanding the context and environment. Otherwise, cases of addiction will continue to rise."

The impact

-Querétaro is a state known for being conservative, where the rights of LGBT populations faced resistance from anti-rights groups but also Catholics, has your art experienced any kind of censorship?

-The first work I exhibited in 2000 was El Guadalupapi, 24 years ago. When I presented it, I was bombarded with threats, attacks, and so on. Over the years, I felt that society in Querétaro was progressing in terms of openness and understanding, and that believers and non-believers could coexist. I thought we were starting to move forward… But today I feel there has been a regression.

Through art, we had gained ground, including institutional and cultural spaces. As artists, we had earned respect for our work and our ideas, and suddenly those doors are closing again. The struggle in this sense is not over. The environment, if we let it, quickly becomes hostile, because that has been my personal experience. I believe we cannot let our guard down as a gay community, as an artistic community, because yes, in Querétaro there is resistance from groups that even portray themselves as our opposites in terms of how we should live, what we should believe.

As a result of this exhibition, "The Origin of Evil," I'm once again experiencing threats. Before, it was through text messages, even newspaper ads. Now, it's through voice messages that these hateful messages from religious and conservative groups are returning, including messages to the gallery where the work is being exhibited.

In the end, it doesn't frighten me anymore. They never succeeded, but it does make it clearer to me that the work I do is relevant. Not only my work, but also the work of those of us who are interested in paving the way for respect and dialogue.

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.