David Aruquipa, a political figure in LGBT history in Bolivia

The activist created Bolivia's first LGBT archive. He and his partner became the first LGBT couple to marry in the country in 2020.

Share

David Aruquipa is an activist with a constellation of titles and achievements that are an indispensable part of LGBT+ and human rights activism in Bolivia. He has served as Director General of Cultural Heritage at the Ministry of Education since 2006 and currently heads the National Unit for Cultural Management at the Cultural Foundation of the Central Bank of Bolivia.

Everything she does is permeated by cultural management and the pursuit of expanding rights. Her body is a political act: from her presence at carnivals to when, in 2020, she and her partner Guido became the first LGBT+ couple to marry in the country.

“It was a political decision,” David tells Agencia Presentes about getting married in a place where, until then, there was no record of same-sex unions. The country's own Constitution, in Article 63, defines marriage as the union between “a man and a woman.” But, “Article 14 of this same Constitution states that all forms of discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity are prohibited, so there is an internal contradiction,” he explains. He recounts all the resources they used in this process, which involved years of patience and perseverance.

Photo: Magdalena Tola

A wedding won through activism

Another key element was Advisory Opinion No. 24 of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights , which states that states must create mechanisms to grant this right, and that there can be no discrimination.

It was 2020, and that December, after more than two years of appeals, they finally obtained the departmental permit. Only then did they begin to make visible the years-long effort to use international pressure to help the Constitutional Court ratify the marriage: “It has been very important because we have managed to use an international legal recourse to address an absence in our Political Constitution of the State, which is the supreme law of the land,” David explains.

Like all historical achievements, this marked not an end but the beginning of a different way of litigating. Couples who followed faced difficulties, but with this advance as a reference point, they were able to gain recognition. No unions were registered in 2021.

Starting in 2022, these cases began to be taken into account, and with last year's legislative changes, LGBT+ couples can now register their unions. David and Guido's case marked a new milestone and made history in Bolivia. This is now part of another of the activist's passions: archives.

The kiss like a Molotov cocktail

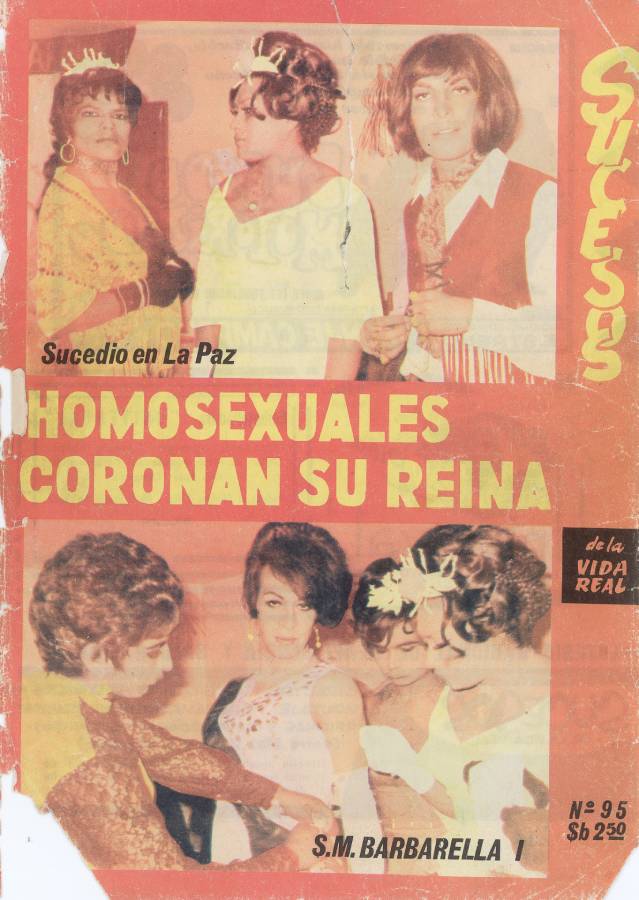

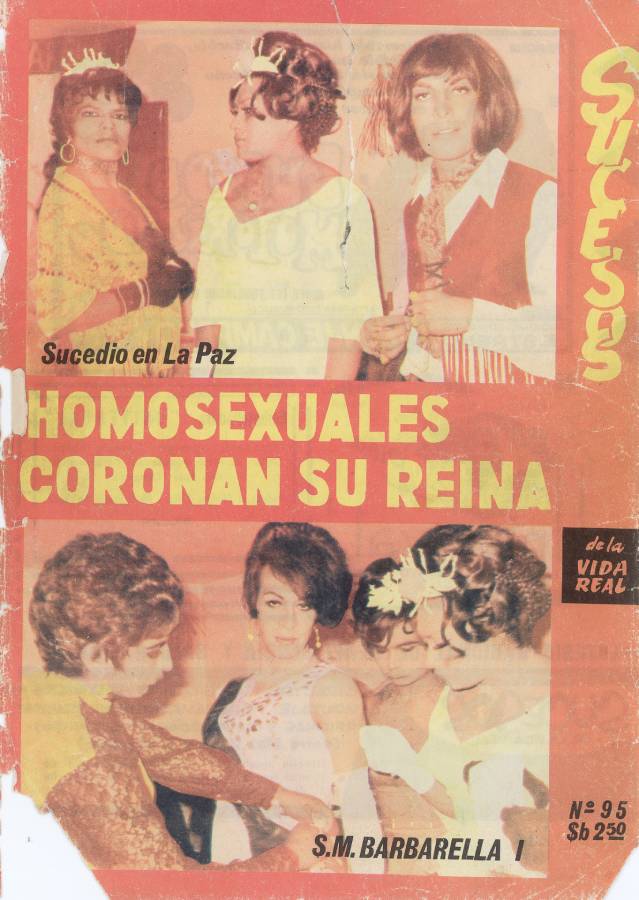

What is the founding moment of the Bolivian LGBT+ movement? There is no specific date, but there is a political event that marked a process of resistance in a time of dictatorship and oppression: Barbarella's kiss.

In 1974, during the festivities of El Gran Poder, a transvestite, Barbarella, approached the dictator general Hugo Bánzer and kissed him.

David defines what happened as “a political statement.” He continues: “It raises for us the need for resistance and for challenging political power. It is a struggle and a visibility of being different, of the diversity of colors and of our existence.”

We queer people know that a kiss can often be more powerful than a Molotov cocktail. And from that union of lips, a ban was issued against trans people and other diverse identities participating in the festivities. Far from being a saddening veto, it was yet another instance of censorship that forges strength, strategy, and history within these collectives. Transvestite and trans identities had arrived at the celebrations by transgressing customs.

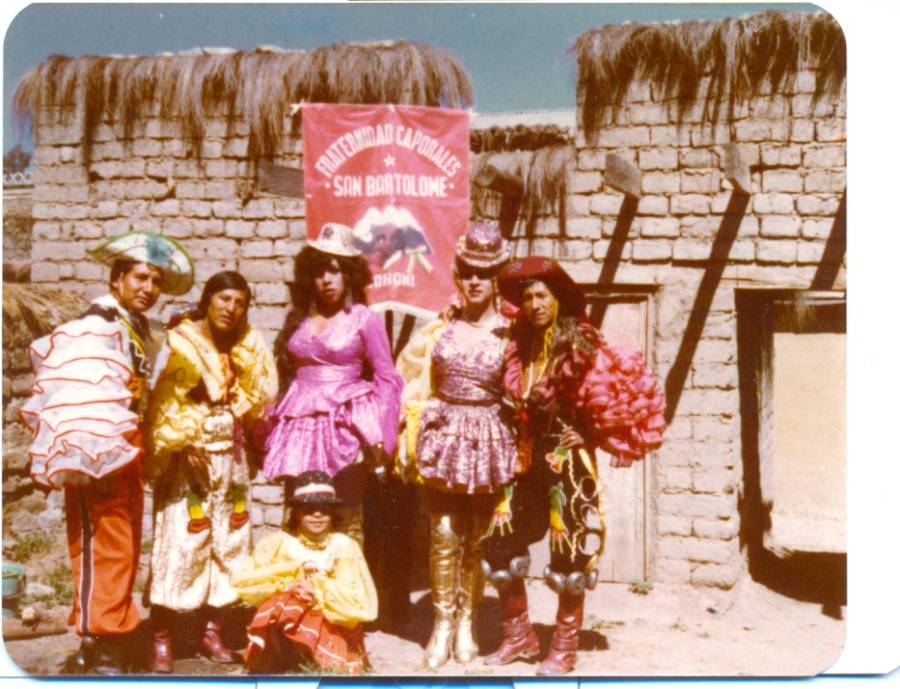

Photo Tony Suarez- Q'iwa Archive

Photo by Tony Suarez - Q'iwa Archive

Photo: Q'iwa Archive

Photo: Eric Bauer – Q'iwa Archive

A story without a patriarchal perspective

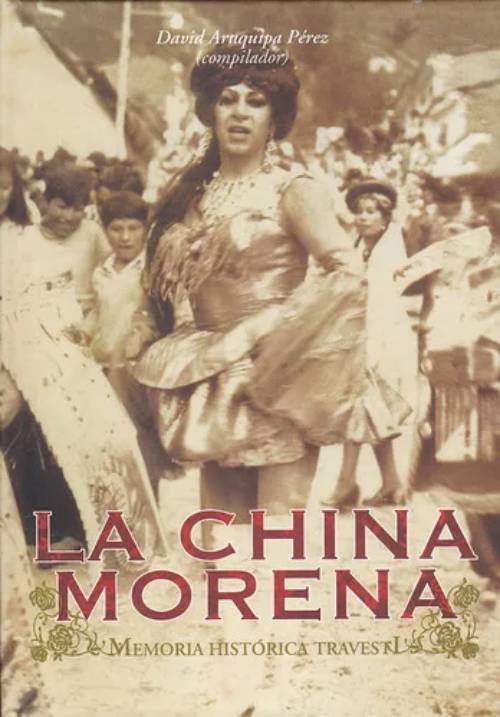

While historically the character of "la china morena" was portrayed by cisgender men adorned with masks and clothing that covered their entire skin, these women arrived with made-up faces and cleavage, with skin and pride. We know this from the voices of those who were there and from David's compilation work published in the book La China morena, memoria histórica a travesti (La China morena, historical memory of a transvestite ).

“Making this visible has been highly strategic for me. It allowed me to tell the story of a social movement, to discuss on equal terms with other social movements that had suffered certain forms of discrimination (indigenous people, people with disabilities, etc.). Then we were no longer the ones without a history; we became just another social movement,” she says, emphasizing the importance of the archive and its dissemination.

“History has been written with a patriarchal and sexist perspective where everything diverse has been excluded. They have burned archives, the stories of our female comrades, and even houses to prevent this evidence from becoming public. We have managed to collect an archive of more than 500 photographs from the 1930s, 40s, 50s, and up to the 1980s,” and thus they created the Q'iwa Archive, which also includes letters, newspapers, and the voices of the survivors.

Preserve the past, sustain the present

For David, the idea of the archive is a living, evolving concept. So much so that for over 20 years he has been using his body to challenge patriarchal traditions and redefine them, giving life to the “Waphuri Galán” .

But what is a Waphuri? In the tradition of Bolivian festivities, this is a hypermasculine, phallocentric character who guides the spinners. The reinterpretation proposed by LGBT+ collectives is another of those transgressions that, far from being merely visual, is embodied in popular traditions to give visibility, pride, and narratives where queerness is part of our history (past, present, and future).

“The Waphuri Galán is this queer character who transgresses the traditional Waphuri figure, transforming it into an effeminate figure with much more sensual movements . He embodies this resistance and visibility of diversity within the festival, even stripping the traditional figure of its power to become much closer to the people.” And it is the people themselves who choose and embrace him. In an LGBT-phobic society, and despite all the complaints this representation has generated from right-wing sectors, it is the people who choose and sustain the Waphuri Galán.

Listening to David Aruquipa's story is to witness the living history of the LGBT+ movement in Bolivia. His actions, his work with archives, and his passionate weaving of international perspectives with his own traditions are all part of the experience. David knows there is still much to be done, and that all of this will continue to build community and archives.

The cover photo is by Magdalena Tola, provided through the interviewee.

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.