Abigail Galindo, the trans woman who documented the LGBT history of Honduras

For 35 years, Abigail Galindo, a trans woman, walked the streets, stages, and parties with her camera. These images of LGBTQ+ history are a crucial part of the Honduras Queer Archive.

Share

TEGUCIGALPA, Honduras . The women in the photograph aren't smiling at the camera, but they look happy. In the image, taken in the Honduran capital thirty years ago, in a park, on a bench, under a tree, four sex workers wait for clients. The night is dark, their gazes penetrating. From left to right pose Gaby Spanik, Bessy Ferrera, Abigail Galindo, and Michelle: four important figures in the trans movement in Honduras.

Flash. A lightning bolt, the night, and suddenly, they are immortal.

In a few years, two of them will be killed, another will migrate to escape the violence. Only Abigail will remain to tell their stories.

But in the photograph — now an icon — they look happy.

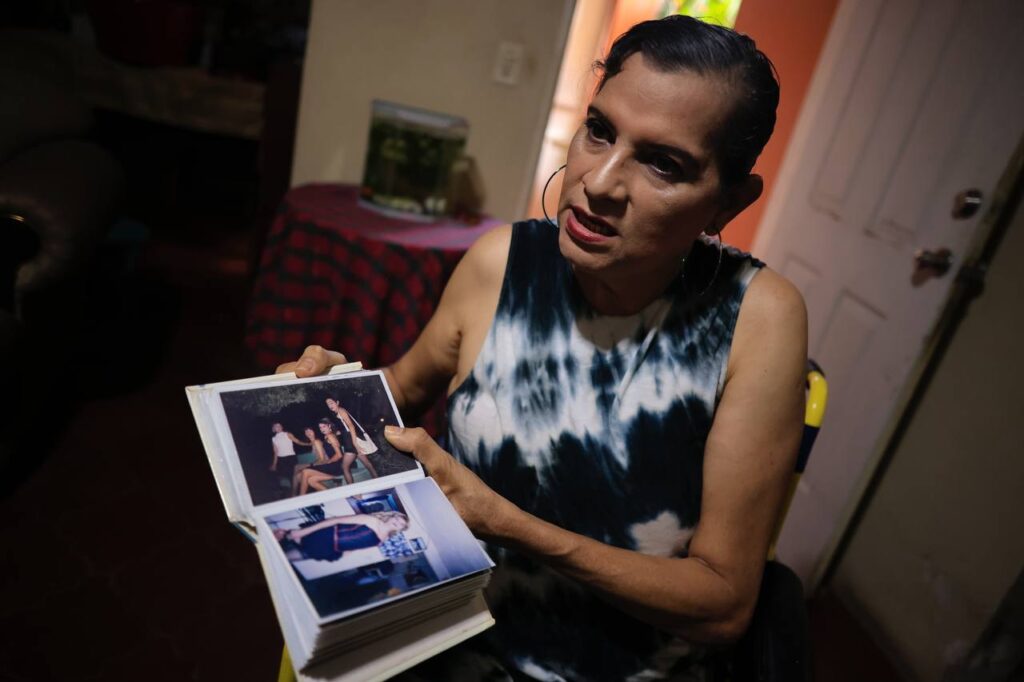

So many photos. They hang on the wall, are stacked in albums, rest in picture frames. At first, they were just the personal collection of Abigail Galindo, a trans woman and human rights defender. She photographed for 35 years without knowing, without imagining . Now she is 52, she left sex work 20 years ago, and her images are part of the collective memory of LGBTQ+ people in Honduras.

They're digitized for Instagram, printed poster-sized, and displayed before thousands. All that remains of Abigail, who once roamed the streets of Honduras' capital in heels, sequins, and fury, is a thin, almost timid figure, moving slowly in her wheelchair, missing a leg. She's still surprised when she finds hundreds of people gathered around her, listening to her.

For most of her life, photography was nothing more than a hobby for her. She never expected, nor would she have dreamed, that her photos would be part of exhibitions or that they would guide tours through fragments of her life. Her intention was to capture memories on 60mm film, to reminisce with her friends about parties, loves, and nights out, once they were old.

"I always loved taking pictures everywhere," she says. "I used to carry around a roll of 36 film. When we went to an event or went out, the first thing I'd grab was my camera, ready to take pictures of my classmates, my friends.".

In June 2022, Abigail met a photographer named Dany Barrientos . He told her about "historical memory" and a project to "reconstruct and deconstruct" the history of people like her : the Honduras Queer Archive , an initiative that sought to prove, through any scrap of paper they could find, that LGBTQ+ people existed. Abigail, with her photos and her stories, was also going to become a crucial part of the living memory of those who remained and those who were no longer with us.

“I took so many photos to preserve my memories,” he says. “Photographs are very important because they are history reflected on paper. If we have a good memory and remember everything, we can explain it, but without a photograph… No story can be told without proof, right?”

The stories behind Abigail's images reveal what various LGBTQ+ organizations have called a transgenocide in Honduras, of which she is a survivor. The rest of her friends, like those posing in the park photo, met the same fate: one night, two men left their homes, said goodbye to their wives, got into a car with tinted windows, and drove through the city with their intentions clear. Bessy was shot to death. Her body lay on the sidewalk where she worked.

One day a client told Michelle, " I'll take you with me to Guatemala," and she replied, " I'm going to Guatemala with the client ." What happened in between is unknown; what is known is that they were able to identify Michelle's remains by her tattoos. Abigail gets chills when she remembers.

—Of those, only two of us are still alive, Campero (Gaby Spanik) who is in Germany and me, who am here .

Here in Honduras, according to the organization TransRespect , this small piece of land between the Caribbean and the Pacific is one of the most violent places in the world for trans people, especially sex workers. Various organizations have dedicated themselves to documenting attacks, murder weapons, court rulings, and everything else necessary to explain the complexity of this violence, but the conclusion is that in Honduras, as in other Latin American countries, trans women rarely live to old age.

— I always tell the girls, "Let's take a picture, because we don't know if it's the last one.".

Abigail's photos in the Honduras Cuir Archive

When Dany Barrientos, the founder of the Honduras Cuir Archive, is asked what he sees when he looks at Abigail Galindo's 700 photos, he doesn't hesitate for a second.

—The genealogy of the community.

Dany Barrientos studied contemporary art at La Fototeca in Guatemala and has a background in documentary and editorial photography. She drew inspiration from projects in other countries, such as the Trans Memory Archive in Argentina, to tell "the other story": the memory of the LGBTQ+ community.

In the early months of her project, she heard from a former trans sex worker who had documented much of the 1980s and 90s. Not many years after the last military dictatorship in Honduras, when the nights were longer, the police controlled the streets, and the first LGBTQ+ collectives were founded in the country.

Abigail says the Archive saved her life. After an accident with boiling water, she suffered severe burns to her right foot and, due to complications from her diabetes, lost her leg below the knee. Death, from which she had escaped so many times, was coming for her. She sat and waited for it. The only thing she was going to leave behind were her photos, and there was someone who promised to take care of them.

— After the accident, before the amputation, she saw that something bad was going to happen to her and I think that was one of the reasons why she lent me the photos — says Dany.

The photos were exactly what I was looking for.

The Archive, which stores all documents related to the diverse population in Honduras between 1934 and 2015 , does not have a physical space. At the beginning of the project, the recovered photographs and documents were digitized and uploaded to Instagram, along with information providing context about what the images depicted: scenes of daily life, scenes from parties, love letters, newspaper clippings with discriminatory news stories, and so on. Hundreds of people from the LGBTQ+ community in Honduras began, for the first time, to see their history reflected . Months after the Instagram account , a series of live discussions began, narrating the story behind each photo and the lives behind each name.

“Here we have our own history”

Grecia Ohara, a trans activist and advocate for LGBTQ+ rights, highlights the importance of the Honduras Queer Archive for the country's diverse community. It allows us to remember the lives, struggles, and work of past generations in advancing the recognition and respect for human rights in Honduras. Furthermore, it demonstrates how it helps to build a national LGBTQ+ identity.

“Whenever we think about LGBT rights here, we’re always consuming international perspectives: those from the United States, Mexico, South America,” Grecia says. “ We also have our own history here. Let’s include Honduran people, our own people whom we recognize as leaders, so that, as a community, we can feel connected to our own people and our own context.”

It is because of this construction of Honduran LGBTQ+ identity that Dany Barrientos highlights the photographic work of Abigail Galindo. Her collection of photos, he says, reveals a fluidity of vision, ease with the use of the camera, and a drive to portray the things she loved and that made up her world.

"I like how the perspective of the large journalistic conglomerates like La Tribuna or El Heraldo, which also portrayed her, is juxtaposed with the way she sees herself," says Dany.

Many of the most intimate photos, such as those she took of her family or lovers, are not part of the Honduras Cuir Archive, but they represent a part of the photographic body that, perhaps, allows us to better understand the figure of Abigail Galindo beyond her role as a representative of the LGBTIQ+ population, trans activist, showgirl or sex worker.

“Lately I’ve been very fond of a section of Abigail’s archives that are photos of her family,” says Dany. “In those images there’s a nostalgia, a very beautiful melancholy, and I can’t help but wonder what aspects of Abigail’s identity contrast with her mother’s identity as a burden, as a rebellion, and what aspects of her mother that she took for herself.”.

—If the photos weren't there, how would you explain who Abigail Galindo is?

—I would say he is an amazing human being with a great capacity to overcome adversity—says Dany Barrientos—with a burning fury inside that can consume everything and also incredible generosity.

The family album

Abigail's house, in an old neighborhood of Tegucigalpa, is a museum, a souvenir shop, and a crumbling ruin. Faded paintings and countless handicrafts hang on the damp walls: paper, plastic, and rubber flowers; a dreamcatcher with colorful feathers; and a portrait of her mother. On the shelves are photos of her family, unused scented candles, and half-burned paraffin candles. There are porcelain figurines and a pile of Motagua eagles, the soccer team she supports. Next to it, carefully placed, is her constant companion: a Canon SureShot 38-60mm camera.

Abigail grew up with five older siblings and one younger brother. She was the daughter of José del Carmen Galindo, an Air Force soldier, and Eva Soto, a seamstress to whom Abigail dedicated a considerable portion of her work. The portraits of Eva Soto painted by her youngest daughter stand out for their natural depiction of domestic life, in contrast to the rest of her work, where artifice and excess were part of the charm.

—I would stand in a place and my mom would be distracted and I would say "Mommy!" and she would turn around and flash, I would take the picture, distractedly I would grab it… I liked it because I took them like that, without posing.

Eva was an old-fashioned woman: serious, domestic, and under the military yoke of her husband, yet dreaming of more. One day, Eva, who had only completed the sixth grade, tried to continue her studies, but her husband set fire to her notebooks.

“It always comes as a complete shock to them.”

Her mother's personality and experiences, plus the years working on the streets of Comayagüela—Tegucigalpa's sister city, precarious and with high rates of violence—shaped Abigail from a withdrawn and even stunned girl into a rebellious, volcanic woman with a sharp sense of humor.

“At first they didn’t accept me… as always, right?” he says. “ In every family, it always comes as a shock. I say that many times it’s not that our parents don’t love us… what they want to avoid is society’s rejection of us. I remember my dad once told me, ‘I’d rather have a thief, a murderer, or a pothead than have a faggot in the house.’”

Her father didn't find out for several years, and her mother, who discovered her daughter's identity through gossip, did her best to hide it. It was in vain. At 16, Abigail would sneak out of her house, backpack slung over her shoulder, wearing a dress and heels hidden, and meet up with her friends, several years older, who hung out on street corners.

—The first time I went out, I just wanted to see what it was like, hang out with the girls on the street, get to know the scene. We'd go to the bars. I've always been tall, so we'd put on makeup to look a little older and they'd let us in. Later, the girls gave me a wig, and I'd look in the mirror and feel good. I felt like that was me, not the one at home.

23 husbands and photographic collections

Three circles of light, camera flashes or spotlights, bounce off a mirror behind her. In the photo from the early 90s, she's standing on stage in a blue and black bikini and a feathered headdress. She's balancing on a pole, smiling. Behind her, well hidden in the shadows, a security guard stands watch, arms crossed and with a look that says, "I'll break your face": his job was to prevent drunken customers from touching Abigail during her shows. The image decorates her room, alongside mementos from her best years.

"That guy over there was head over heels in love with me," she recounts, "but I didn't even notice. 'We can't have a romantic relationship here,' I told him, 'it would have been dangerous.'".

It wasn't that danger was lacking, but neither was love. One of her albums is dedicated exclusively to her 23 partners who survive frozen in time. They lie carefree and naked, smiling at the camera, defenseless. She remembers them as "my husbands," and 22 of them are dead.

Each photo from her nights out tells its own story. For years, Abigail dominated the gay bars and clubs in Comayagüela and Tegucigalpa, where she would transform into Selena or Thalía for a few minutes in exchange for food and unlimited drinks. She earned more from clients on the street, and despite being a 16-year-old trans girl, she was already a nightlife icon.

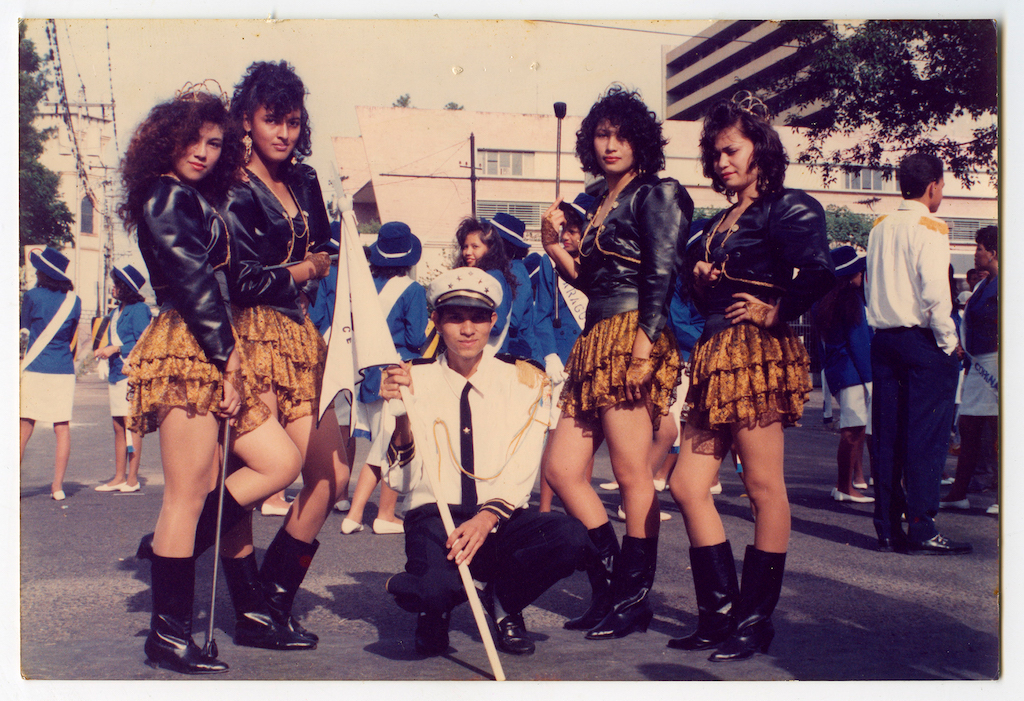

In one of her photographic collections dedicated to that era, she can be seen at parties and shows, walking catwalks in beauty pageants, parading through the streets in a baton twirler outfit or a feathered costume during one of her shows.

—I'm not going to say that everything was dark, gray, and black. There have been beautiful moments too.

In those moments, scattered across the unchanging time of the small blue box where she keeps her photos, someone appears smiling. A Halloween costume. Military clothing. A naked man. Her mother's face. Colorful balloons. A lit cigarette. A corset. A small dog in a purse. A lover. A beauty queen with her tiara. A woman dressed as a man. A Catholic baptism. Two men kissing. An impossibly blonde wig. A heart-shaped pillow. Her mother's face. A chubby, pink baby. A thigh with a heart tattoo. A rainbow flag. A shirt that says "The guy next to you is gay." Six women dressed as men. A poster of a naked Pamela Anderson. A majorette parade. A leopard-print bra. A person dancing. A person who died of AIDS. A person who was murdered. A person who fled the country. Someone laughing. Another lover. Her mother's face.

Memoirs of Sex Work

There are no photos of the customers.

Abigail says she started working as a sex worker at 17. In thirteen years, she had offered her services to all kinds of men: professionals, diplomats, politicians, military personnel. They wanted to see her dance while she masturbated, talk about their problems without being judged, sleep with someone of the same sex. There were also those who came with requests that, so many years later, still disgust her.

And there were the police, the military.

Encountering them could mean a good paycheck or spending the night in jail. In the late 1990s, Abigail recounts, the mayor of Tegucigalpa, Vilma Castellanos, ordered the removal of sex workers from the area around the Hotel Honduras Maya, the most elegant hotel at the time and where clients paid the most. During this period, she was arrested 25 times for public indecency.

“We were running around like deer, up and down the hill, because they wouldn’t let us work,” she says. “The patrol cars were always coming. Once they took me to the Ulloa police station in a pickup truck. They took me eight other times. The police were also in plainclothes, but armed to the teeth. They forced us in, they kidnapped us. They took us through Ciudad del Ángel. It was all dirt roads. It was pitch black, and they told us, ‘We’re going to kill all these bastards here.’” Abigail’s voice narrows to a single, monotonous thread, the words slipping between her teeth. “We all hugged each other,” she continues, “we started crying and saying goodbye. And the police just laughed. We thought, ‘Oh well, we just have to hold hands so that when we’re dead we’ll go together.’ But they started shooting into the air. And then what did they do? They put us back in the truck and took us to the police station, where they raped us .” While they were raping us, they told us they were going to kill us, that we were assholes, that we were worthless. That no one would even cry for us.

He has no photos of any of that, but he doesn't forget.

How to remember

Abigail thinks about how she wants to be remembered. She thinks about it because her friends are usually remembered for how they died. She wants to be remembered for what she lived through, for the art she created, for the portraits of her loved ones, and also for those last photos she took of friends and colleagues before they too became statistics and went on to live only in her photographs and in her memory.

Although she no longer dedicates herself to photography as much as before, Abigail Galindo has begun to explore new interests: she is writing a memoir, leading a tour of the Archive, acting in short films, and she began attending a Latter-day Saint church where she found a new mission: to change 200 years of Mormon tradition.

—The bishop tells me, “I don’t know how to address you.” “ Anything goes here on earth ,” I reply, “so you’re going to call me Abigail because that’s what I feel comfortable with. Don’t call me anything else, unless you’re going to give me a check with money.”—she laughs.

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.