Fernando Us, the Mayan spiritual guide who embraces his diversity

Fernando found meaning and belonging in the ancestral practices of his people, where he was ordained as a priest. In this interview, he recounts what it was like to make that journey as a person of diverse sexual orientations and gender identities.

Share

Maya K'iche ' spiritual guide . He was born in the village of Macalajau in Uspantán, Quiché, in the western highlands, about 300 kilometers from Guatemala City. He is a sexual dissident, the son of Natalia Álvarez and Reyes Us. In the 1970s, his father, a catechist and community leader, was a member of the Committee for Peasant Unity, an organization that sought to improve working conditions in rural areas and access to land. During the internal armed conflict, his father was killed by Guatemalan military forces, and a couple of years ago he was beatified by the Vatican along with other farmers from Quiché and a Spanish priest.

Fernando was Catholic until he was 20, and during what he calls his "sexual crisis," he decided to leave the faith. Guatemalan Catholicism retains some indigenous roots, and it was in his spiritual quest that Fernando found meaning and belonging in ancestral practices, where he was ordained as an Ajq'ij (Mayan priest).

Fernando greets us for the interview at the Association of Mayan Priests. It was founded on the outskirts of the capital in 1994. From his appearance, he already breaks gender stereotypes – long hair, fingernails decorated with blue polish. He told us about his struggle to resume his path as a dissident spiritual guide in a conservative social context marked by syncretism.

During the era of colonial missions, the infrastructure of Catholic churches was imposed on the original sacred sites. Many Catholic ceremonies and celebrations have their indigenous counterparts, occurring on special dates or in significant rituals of the Maya people. For example, Holy Week coincides with the meditation period called Wayeb in the Maya worldview. It is a week of transition between the year that ends and the Maya New Year. From the Maya philosophical perspective, this period is a "timeless time" because there are no guardians. The elders go to council and it is advised not to go out during those days, only to meditate, because those in charge of watching over the land, the nawals, are occupied.

The Association of Mayan Priests of Guatemala currently has more than 50 spiritual guides among the K'iche', Q'eqchi' and Mam peoples.

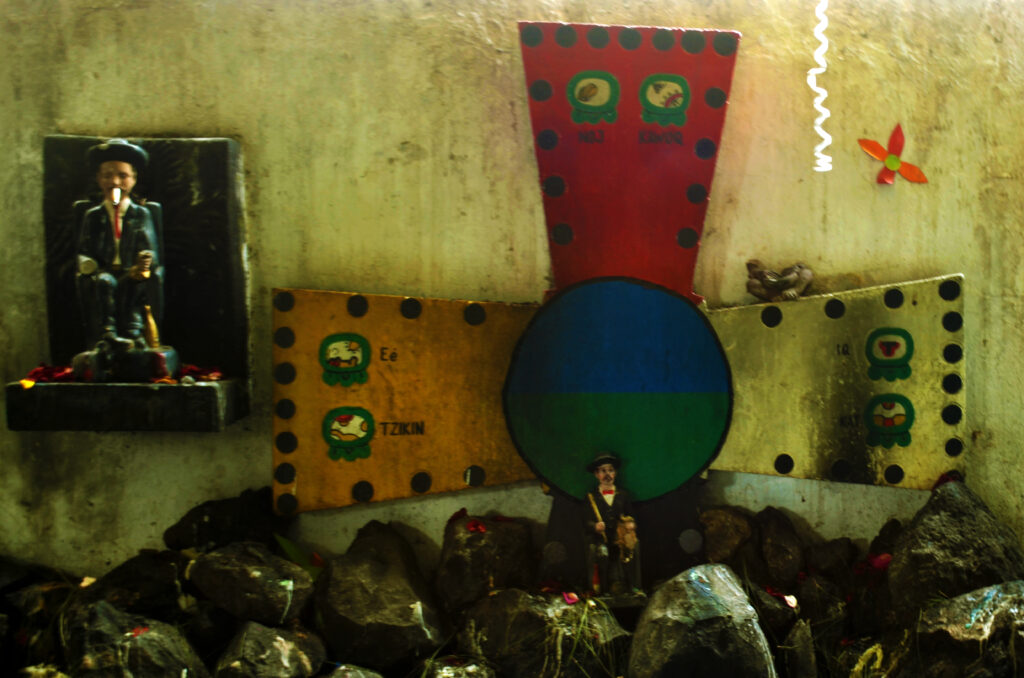

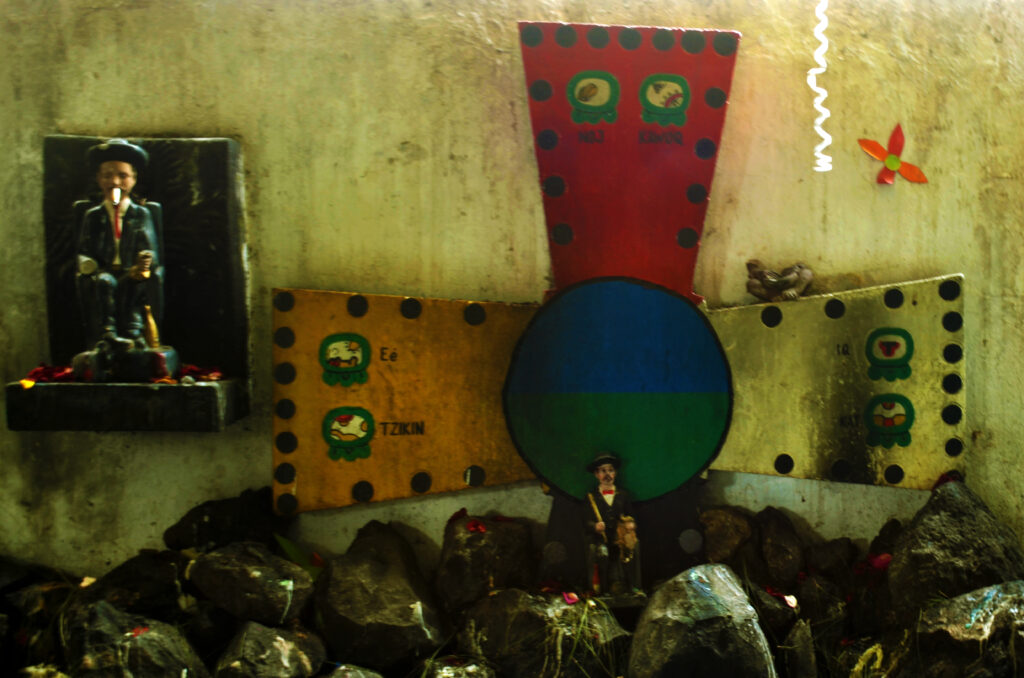

The saint of the excluded

“In our association, there’s a kind of syncretic combination, although I don’t like that word. Our temple has Grandfather San Simón, a deity, a saint recognized by ‘the pagans,’ as the Catholic Church calls the excluded. Grandfather San Simón receives and attends to everyone without discrimination, or at least that’s Fernando’s idea. ‘You receive requests from sex workers, sometimes gang members, people experiencing homelessness, and members of the LGBTQ+ community. For us, he’s Grandfather ‘Mam Ximon,’ the grandfather. Those of us here have been trained in Mayan spirituality, with the calendar, the numerology of our people. With these resources, we attend to people’s needs. It’s not divination. There are gifts for interpreting body language, images. Our learning with our oracle, our tzité (red bean), our staff, teaches us to count the energy of the day,’” Fernando begins to explain.

– How long have you been a spiritual guide?

“I’ve been a spiritual guide for ten years. My initial training began in San Juan Comalapa, 52 kilometers from the capital. It lasted nine months, and I received my staff. The staff is the object of the Ajq’ij. It is the core of the gift or power of the Ajq’ij, or spiritual guide. It is what protects them, their nawal. I graduated in Iximché, a pre-Columbian archaeological site. But I didn’t take up the profession or practice it. When I wanted to, I faced many difficulties. Until I met a guide for the LGBTQ+ community on Facebook, thanks to a celebration by a religious brotherhood in Santiago Sacatepéquez. I was 35 years old, and he was 24. I felt a connection with him, even though I wanted this second part of my training to be with a woman. He trained me and told me, ‘If you want to practice now, you have to go through the process again.’ And I had to go through the nine-month process again.”

"I had two celebrations, one with the men and one with the women."

Ten years ago, Fernando went to the Association and was attended to by the spiritual guide Nana Angelina, with whom he had his first consultation about a matter of love, she told him what his purpose in life was.

– When I joined the Association of Mayan Priests, it wasn't a topic we discussed. They asked me questions about the nawales and the red beans. Then they went to consult amongst themselves, came back, and accepted me. The topic of sexuality wasn't and hasn't been an issue. There are jokes, and I see them more from the men because they don't know how to treat me. Sometimes, jokingly, they call me "Nana." At the first celebration I had here with the women spiritual guides, they told me to participate with them. That we women organize it. Everything related to the food, the flowers, the ceremonial materials—everyone is invited, but we women organize it. I've already had two celebrations.

– Have there been any situations of violence or bullying related to sexuality within a community of spiritual guides?

– We have no cases of sexual harassment or gender-based violence. The board of directors is made up of two men and two women; there's diversity without having negotiated it. The rest of us are active members and part of the assembly. We have a Kamal Be; he's the one who directs our spiritual work in the Association. He's the path opener, he guides our way. Tata Chepe is that elder, he's a K'iche' Maya from San Pedro Jocopilas, and he guides our spiritual work. Then we have a president who largely directs the administrative work.

Consultation day at "Toj Ajmac"

We asked Fernando for permission to take some photographs during a ceremony. The Association is a space with several rooms that function as consultation rooms, where guides receive people. In front of each room is a small space with a kind of fireplace divided in two. On the right side, ceremonial items are placed as a way of giving thanks, and on the left, offerings are made to cleanse the energies. Fernando puts on his red ceremonial scarf while explaining the energy of the day. It is a Toj Ajmac day, a day for the guides to make offerings.

– What does it mean to be on a Toj Ajmac day?

– Toj means to pay, and translated it's been said to give thanks. But in our spirituality, one pays for what one wants and pays for what one has already received. A Catholic man told me the other day, "You all seem to always be in debt." Well, something like that. Toj bal is the closest thing to Karma. It's like you're carrying a debt. Sometimes a Toj comes up in a consultation, and we tell the person that it's not theirs, it's their lineage's. We have to pay to be freed, to stop an illness, to no longer suffer. Paying to keep eating is more or less the logic of our spirituality . And Ajmac was initially called secret. Everything has a secret, and it's not that a secret is kept per se, but rather that all energy is sacred and has a way of being treated. For example: The water of the river cannot be disturbed. You can't throw stones in it or jump in it. Jumping in the river disturbs the water, and that's a secret. Because if you don't, you'll be frightened later; that's our belief.

Fernando, when he speaks of secrets, refers to oral traditions, those stories passed down from generation to generation. It's the energy that governs. The Catholic Church interpreted that as sin. Ajmac also includes sexuality, and it has its own "secret." "The people who come to us have various problems, and we try to support them from a spiritual perspective. Sexuality isn't disconnected from the physical; these are energies that must be addressed."

– What does fire mean to you as a spiritual guide?

– Fire is how I communicate with the elders, with the nawales, and with people's spirits. In many cases, I invoke the spirit of the person's nawal, their cajaleb, which translates to their carrier, that which sustains them. Not only does my body sustain me, but also my nawal, my lineage. When someone comes to me with difficulties, I suggest calling upon their spirit, their nawal, who will accompany them through those life difficulties. This is parting the fire; the answer or dialogue we can find, for me, is possible through fire, and it is related to the Toj, whose graphic representation is a flame.

– What is it like to be a sexual dissident within a Mayan community? There are cases of trans women in various departments across the country who have spoken about violence from within Mayan communities and against Mayan authorities. What are your thoughts on this? Have you experienced it yourself?

– I believe that religion is a system for transmitting values and subjugation. We have been under a Christian tradition for many years, and we are not outside of those relationships of violence. It exists where there is greater evangelical influence, in indigenous communities because women's bodies are subjugated, and sexual dissidence is criminalized or at least denigrated . In my case, I had internal conflicts during that process of coming to terms with my sexuality. I knew I was gay, I pretended not to notice, and I thought that one day I would wake up, have children, and everything would be resolved, but it wasn't like that.

When I started looking for guidance, first visiting those closest to me—priests, nuns—I found no answers. I remember my mother listening to a well-known Catholic priest on his radio program. I went to see him, and he told me that everything that had happened to my father during the war, and to my family, was because of bad things we had done, including me (referring to sexuality). I was 17 years old, and far from bringing me peace, I began to feel even more distressed because I was living a life I didn't want. I didn't want to be gay. I felt sinful, dirty; it wasn't something I could share with my family, something I couldn't show them, but that was who I was.

When I first started talking to the guides, they all told me more or less the same thing: "When you were born, the moon wasn't in the right position," "Your mother may have eaten more of one food than another," or "Perhaps it's karma that's what you're going through." I was fortunate enough to meet my teacher, José Telón, who, aware of this aspect of my life, took me on as his student, guided me, and agreed to train me.

My second teacher, Anibal Culajay, with whom I resumed the path of spiritual guidance, openly accepts my sexual orientation and has been a great teacher in caring for people.

– How would you describe your sexual identity at this moment?

– I would say that the first identity I assumed in a country as racially divided as ours, one might not realize what it is even if one sees it, even if you look at it, you might think you're not that. During the peace accords process in 1996, with the arrival of the Peace Mission in Guatemala and the debate surrounding the Truth Commission report , testimonies began to be requested from survivors of the internal armed conflict. My mother was one of the first to give her testimony, first to REMHI (of the Catholic Church) and then to the Truth Commission. There, I received a profound shock when I realized which side of history we had been on .

My family was affected by the conflict, and I began to find a way to connect with others. The first thing I asserted was my Indigenous identity, even though I was already struggling with my sexual identity. Later came the sexual affirmation. And yes, there was a powerful period where I strongly asserted my identity as part of the LGBTQ+ community. Today, I feel that all these pieces of my life are finally finding their place within me. I identify as a sexual dissident, although I know that dissent can generate a sense of resistance, a discomfort with the very acronyms (LGBT) that impose so many limitations on us—so static, so rigid.

"The first thing I asserted was my indigenous identity."«

– Don't you think the term can be very binary as well?

Fernando: It could be, and I've considered it, but in spiritual work I use the binary world; there is feminine and masculine energy. It still serves me well; there are nawales that are feminine.

– What message would you give to young people who are searching for their spirituality?

– I think the first thing to say, not only to young people but to everyone, is that it's necessary to see, accept, and acknowledge oneself. Spirituality is a dimension that not everyone necessarily shares or accepts. As Fernando Us, I say that we are spiritual beings and have a profound spiritual dimension that at some point becomes our only resource for refuge and protection. But hopefully, young people can seek spirituality as an affirmation, as a reaffirmation of their identity, their culture, and their worldview, and not as a refuge from violence and death.

The practice of spirituality has led to persecution, and even today, some of that persecution is directed at spiritual leaders who defend their territory and resources. Therefore, for me, spirituality is also a political act. Calling it a religion is complicated for me because of our history, such as spiritual control, moral control, and the sanctions imposed on sexual diversity. I encourage young people to embrace themselves, and if spirituality is a way for them to do so, then they should use that resource.

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.

1 Comment