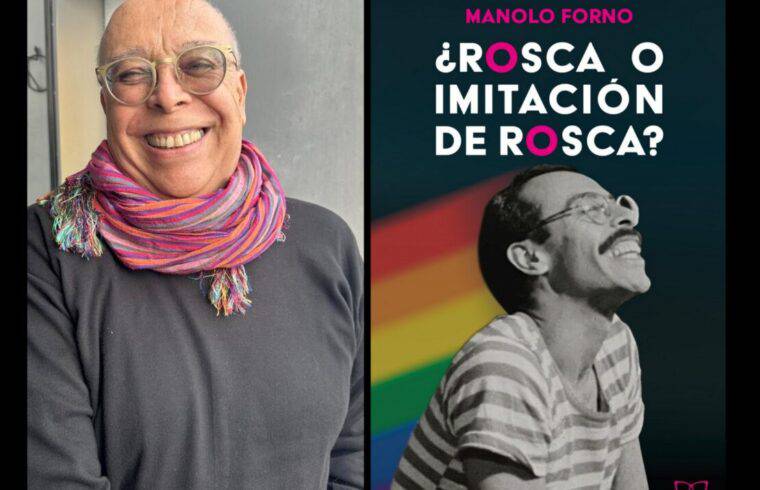

Manolo Forno: “The closet leads us to be in a submissive condition towards the heteronormative system”

Peruvian activist Manolo Forno published the book ¿Rosca o imitación de rosca? where he tells his life story and the history of the LGBT movement in Peru.

Share

LIMA, Peru. "A ring or an imitation of a ring?" are the memoirs of Manolo Forno, a Cusco native, a historic gay activist who recently turned 70 and one of the founders of the Lima Homosexual Movement , the oldest LGBTQ+ organization still operating in Latin America.

It's not his entire life, as he very aptly explains to Agencia Presentes in this interview. But it is part of it and of what he wants to leave for future generations, to share the pain and joy, the wounds and dreams, the frustrations and hopes of a community that continues to fight for its rights in Peru in the face of fundamentalist advances and the absence of laws to protect them.

How to tell the LGBT+ story in Peru

-How did you decide to write your memoirs?

-For some time I'd wanted to write about how the LGBTQ+ movement had been born, how it had developed, how the relationships between identity groups and organizations had been built. What was really happening, whether everything was alright, and how we could redefine and reconstruct our history. I've always said that our history is behind the scenes, or what many people know about us is based on the perspective of heterosexuals and under the rule of heteronormativity. That gave me the encouragement, the drive, and the desire to write my memoirs.

On the other hand, when I finished my master's degree and tried three times to write my thesis in Gender, Sexuality, and Public Policy, I couldn't find that connection between what I had actually experienced and what the methodological structure for writing a thesis required. And every time I tried, I abandoned the attempt. That led me to think that I had to write. But from what perspective? From my own . What did it mean to be gay in Manolo Forno's life? Not only from the perspective of myself, of identity, of this sense of self, but also to analyze the social and political context of what I was experiencing at that time . And to analyze our movements within the LGBTQ+ movement. In that way, I began to construct my memoirs, to develop them, to write them down.

-What was the writing process like, and how long did it take you to start and finish the book?

-I went through a process of about a year and a half, during which I finally got the courage to do it. It was around November or December of last year when I participated in a writing workshop, and that's when I started telling stories. At the same time, I tried to identify the key events outside of the public and political arena that had left their mark on my life. And then another six months was spent dealing with the book's acceptance by the publisher and the proofreading by the copy editor.

Telling stories, a fundamental act

-Why are these testimonies important?

These testimonies are necessary because they show us not fantastical beings, but real people who have clearly experienced many things. They reveal what bullying, violence, and sexual abuse mean in a society that constrains us and constantly reminds us that we are outsiders. That we don't have the same rights because we are different from them, and that, moreover, society has been built for them. And that it's better for us to understand that the only way to experience it is by being like them.

So, I started writing, taking all these points into account, so that people who have experienced their situation—whether due to sexual orientation, gender identity, being gay, lesbian, trans men or women, or non-binary—can identify the commonalities between my experiences and theirs. And what we can do to bring this out into the open, not behind closed doors. Because what isn't named doesn't exist, and that's fundamental. We are political beings; we have to move forward. That was crucial for me.

What I hope is that all young queer people can read what I've written. If any of them identify with it, they can find and see how I resolved it. For me, one thing is very clear: the closet, the private world, only leads us to be in a submissive position to the heteronormative system, to the patriarchal system that has shaped us. And we have to redefine it, rebuild it, come out of there, transform things, and live our lives with pride and dignity for being queer, gay, lesbian, non-binary, intersex people. With great honor, with great pride, with great dignity, I face this society because I am a person.

The personal is political

-You recently married the love of your life, with whom you have been together for 29 years, what is the secret to having such a long-lasting relationship?

I got married in Mexico recently, but I've been living with Martín for 29 years. I don't think there's a secret; it's about continuous reflection on your personal journey, including your family's origins—it's like creating an internal intersectionality. Beyond that, it's about having the capacity to accept the other person as they are. We can't think that we're getting involved with someone to change them. Instead, through this process of shared reflection, we find and build a relationship based on consensus. It's about not hiding things from each other, not lying to each other, speaking clearly, and when faced with the obstacles and things that entangle our life as a couple, we start talking, finding ways to resolve them. And for that, we have to reach a consensus.

Now, if there are thorns, wounds, stories from our past lives that prevent us from reaching a consensus with our partner, that's where we need to turn to psychotherapy. I go to psychotherapy, my husband goes to psychotherapy, each of us separately, because we believe it's important that, to find fulfillment in our lives and have the necessary resources to love each other, experience pleasure, have trust, and build something together, we must resolve the knots we each carry as individuals.

That involves betrayals, insecurity, bullying, violence, discrimination, sexual abuse—many things. It means the relationship is constantly evolving. We've had moments when we've thought about separating, but after reflecting on that, we've asked ourselves why and accepted that this is who we are. We're different; he doesn't have to change me, and I don't have to change him, so we move forward.

Another important aspect of this consensus is accepting people as they are. For example, I am openly out, but Martín is not. It hasn't been easy for him to live with Manolo Forno, and it hasn't been easy for me to live with Martín. We've worked on this for a long time and reached agreements; we know how to manage conflicts effectively through consensus.

The songs of life

-Your book is very musical, what did you want to reflect with that?

The book has six songs because those songs are very important as part of constructing my memory within the history of the LGBTQ+ movement. Sandro's song, "Yo te amo" (I Love You), has a very clear connection for me: loving someone of the same sex when you were 17 years old and the topic wasn't discussed at all in 1970. For me, it was about "the way your eyes throb, I can sense that you must be suffering just as I am because of this situation" of loving each other, and it marked me for life. The Alaska y Dinarama song that's part of "A quién le importa" (Who Cares), that was when Manolo was already developing his queer identity, facing life, beginning to feel proud, and wanting to achieve a dignified life with respect for human rights like everyone else.

The other song ("Save Me") is a song that reminds me a lot of my work in Villa El Salvador and what it means to be involved with an organization there. And what it means for them to work in conditions of extreme poverty and face life's challenges because they are brown, because they are poor, and because they are gay or trans. That song really moved me, and I remember it because of a project I did with children.

The final song ("The people united will never be defeated") is an altered song, because that's what I hope the LGBTQ+ movement will take up. Take up in the sense that, given the current political context and circumstances, the only option left is to unite, reach consensus, build an agenda, and confront the patriarchy and heterosexuals, asserting that heteronormativity only generates structural violence against us.

The value of art

-In your book you recount how theater, on the one hand, and therapy, on the other, helped you heal a series of painful wounds left in your childhood, adolescence and youth. Would you recommend it to young people who are currently suffering?

– Theater helped me accept myself, to recognize myself and to know that I had these painful wounds. Theater helped those painful, bleeding wounds that were tearing at my life to heal and gave me the strength to move forward; moreover, on the one hand, it gave me tools to build resources to protect myself; and, on the other hand, to understand the society around me, and, finally, to get to know people.

Through therapy, I've encountered all the life processes I thought were closed. But in reality, they weren't; they were open and hindering the strengthening and longevity of my relationship with Martín. I needed to address them and explore them with someone who could help me, not give me the answers, but allow me to analyze them so I could make the right decisions in my life. That has been important.

I believe that for all LGBTQ+ children, teenagers, and young adults, but also for others, theater helps you see the world anew , to see people anew, to get to know them and identify with them. And therapy helps you find within yourself, in your very being, those things that can be both good and, at the same time, a burden that makes you close your eyes and prevents you from moving forward. Because what's important for us is that we can have a dignified and proud life in which our rights are respected.

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.