Comprehensive Sexuality Education (CSE) in Quechua: Against racism, from the perspective of sexual and cultural diversity

“Comprehensive sex education has always been narrated from a white perspective,” say the authors of Kachkanchikraqmi. The book, which stems from LGBT+ and Indigenous journeys, proposes an intercultural perspective of active anti-racist agency and seeks to influence classrooms and feminist movements.

Share

“ Isn’t it crazy that there’s almost no comprehensive sex education material in Quechua? ” Josefina said to Mariana one day while they were preparing their classes. That question opened up a whole new world for them. It was the height of the pandemic, and the neighbors in the La Boca neighborhood of Buenos Aires were “practically living together” to cope with the lockdown and their lives. Josefina Navarro is a Philosophy professor (University of Buenos Aires), a Quechua woman, and a Quechua activist. Mariana Labhart is an Anthropology professor (University of Buenos Aires), a specialist in comprehensive sex education, and a member of LGBTQ+ collectives.

Debates, discussions, and research began in the pedagogical, academic, and activist fields. And so ESI en Quechua , an interdisciplinary collective that produces content and approaches to gender and diversity from an intercultural .

Intersectional and intercultural ESI

“I’ve always been active in spaces made up only of Indigenous people or Indigenous women, ” Josefina explains. “This is the first time I’ve left that space. For me, this is also a safe space, characterized by friendship and trust. So I’m not afraid of epistemic extractivism.” That is, the appropriation and objectification of knowledge in order to gain symbolic capital within the academic establishment.

Each woman contributed from her own experience and background, but at the same time, they allowed themselves to rethink their own certainties based on the other's contributions. “I come from the LGBTQ+ community,” Mariana explains, “and she comes from the Indigenous community. But it's not that she contributed all the Quechua language and I contributed comprehensive sex education. What was interesting was what happened as a result of those exchanges. It was an excuse that allowed us to generate debates, discussions, and agreements.”

The pandemic continued, and the Instagram profile they had created to promote Comprehensive Sexuality Education (CSE) in Quechua grew richer with more and more educational resources. They had enough material to develop workshop proposals for use in classrooms. And so they went, training others and receiving training themselves, while exploring the theories that supported this intersection between CSE and anti-racism . The idea of systematizing this experience in a book came about naturally.

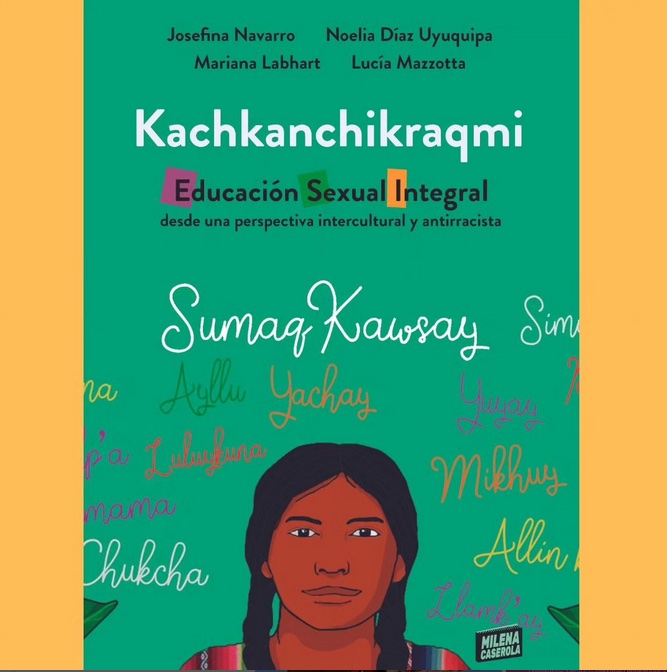

This month sees the release of “ Kachkanchikraqmi. Comprehensive Sexuality Education from an Intercultural and Anti-Racist Perspective ,” edited by Milena Caserola. A possible translation of the title Kachkanchikraqmi is “we continue to be, we continue to exist.” Its premise is that a feminist world cannot be anything but anti-racist.

Noelia Diaz Uyuquipa, a social worker (UBA), Quechua speaker and specialist in health and ESI, and Lucía Mazzotta, an anthropologist (UBA), feminist and specialist in ESI, also write there.

urban

Ayllu

There is a word in Quechua that means both family and community: ayllu . It relates to kinship and affection, as well as sharing a common perspective on the land and nature.

This book grew in the ayllu . Two indigenous women, two non-indigenous women, embodying it through action, putting into play the conceptualizations of interculturality, with dialogue, listening and also conflicts to resolve.

When they asked themselves, “How can we visually convey all these discussions?”, the answer came from Paula Franzi, Camila Ramírez, and Bellota . They didn't want to repeat those “sad, colorless, illustration-less” pieces. They say, “It was important to create high-quality, eye-catching materials with color so that the language would reach a wider audience and spread the word” about the anti-racist struggle.

It is an ayllu : all the people who participated live or lived in the City of Buenos Aires or the Buenos Aires metropolitan area, where it is estimated that a quarter of the country's indigenous population lives but where intercultural educational policies are scarce .

“Do only racialized people have to be involved in ending racism? It’s like thinking that only women have to get involved against sexism. All of society has to be committed,” Mariana emphasizes. She elaborates: “We built it from a very loving place, from the trust of being friends. We were able to disagree, discuss, propose, and exchange ideas, not only in relation to Indigenous identities, but also to our sexual identities .”

Knowledge from everyone, for everyone

The book presents academic works in accessible language and proposes five teaching sequences for working on Comprehensive Sexuality Education (CSE). It provides audiovisual resources and a calendar with significant dates. While designed for classroom use, the material also aims to engage with the feminist movement itself . It understands interculturality as a sociopolitical perspective. This edition does not include topics typically associated with CSE , such as abortion and gender violence, but the table of contents is surprising: it addresses food sovereignty, memory processes, and territorial struggles, among other topics.

Linguistic racism is particularly prevalent: ignorance of the diversity of languages spoken in our country leads to violent practices and linguistic deficiencies among racialized people. Often, schools focus on forcing students to become "perfect speakers" who conform to the norms of the Royal Spanish Academy (RAE), engaging in practices that discriminate against and stigmatize other grammatical structures originating from Indigenous languages.

“ What knowledge is present and what is absent in the curriculum design developed by the Ministries of Education ? For example, in History: why not prioritize Indigenous struggles of resistance to colonization, Indigenous participation in the wars of independence, and the unique history of each people? In Literature, do we teach Indigenous authors? What place do we give to Afro-Colombian cultural production? In art: what aesthetic is prioritized or what aesthetic is taught? What music? Do we teach traditional folk songs?” These are some of the questions raised by this collective work.

What is interculturality?

Interculturality is not merely the coexistence of cultures, nor even their interaction . It is a profoundly political concept that analyzes and denounces the power relations that prevent egalitarian intercultural relationships. It is a perspective that challenges stereotypes, prejudices, and inequalities with the aim of building more just and inclusive societies. Therefore, it is not simply a matter of translating content from a Western perspective into an Indigenous language, or of incorporating Indigenous themes. The challenge is to mainstream this approach across all areas of work.

“I’m not interested in that idea of interculturality as simply getting to know other cultures,” Josefina acknowledges, “but rather as a broader political project that includes the right to territory from an anti-capitalist perspective . It’s not about saying how beautiful these cultures are , but about understanding that there is a political dispute over world paradigms .”

Telling the stories of Indigenous LGBT people

Being a feminist doesn't make you any less racist, we say. Just as you can be sexist while using perfectly inclusive language, you can also teach comprehensive sex education and be racist. Sometimes you're actively aware of it, and often, you're completely unaware of it.

The Peruvian sociologist Aníbal Quijano stated that structural racism is related to a way of organizing the world, involving an unequal valuation of people that has economic, epistemic, and cultural implications. We can also recall that the American countries were founded on the back of an Indigenous genocide—which continues to be largely unrecognized by society—where the population was classified in racial terms: white people of European descent were valued, while Indigenous and Afro-descendant people were categorized as inferior.

“Often LGBT issues are told from a white perspective, and we choose to tell them from an indigenous perspective,” Mariana points out, referring to the interview they conduct with Quillay Mendez , a dancer and folk singer, “a transvestite queer person from the Omaguaca nation.”

“We,” Quillay reaffirms, “ sexual dissidents, have always fought alongside women and men. Gay men, trans women, lesbians. In some communities, we were considered equal to the yatiris, the wise people, who could understand these two energies that exist within an Andean worldview. I like to say that we are going to transvestite the qhari-warmi (man/woman) as a way of breaking down the binary established by the colony and the church .”

Feminist movements have been gaining influence on political agendas, while Indigenous, Afro-descendant, and migrant struggles have less social support and public visibility. There is a wide variety of activism demanding that the anti-racist struggle be put at the forefront. And this book is part of that debate.

With your permission, gentlemen / I will sing at your wheel

Although I'm half-dark / but I won't stain them

Love is as diverse as sunsets

A large, open sky / Multicolored flags

My voice and my feelings / I don't give them to just anyone

Respect the bodies of all our female colleagues

Excerpt from the verses of Quillay Méndez

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.