Our codes: a journey to the Trans Memory Archive book

Why the book Our Codes is a contribution to the symbolic and historical construction of trans memory.

Share

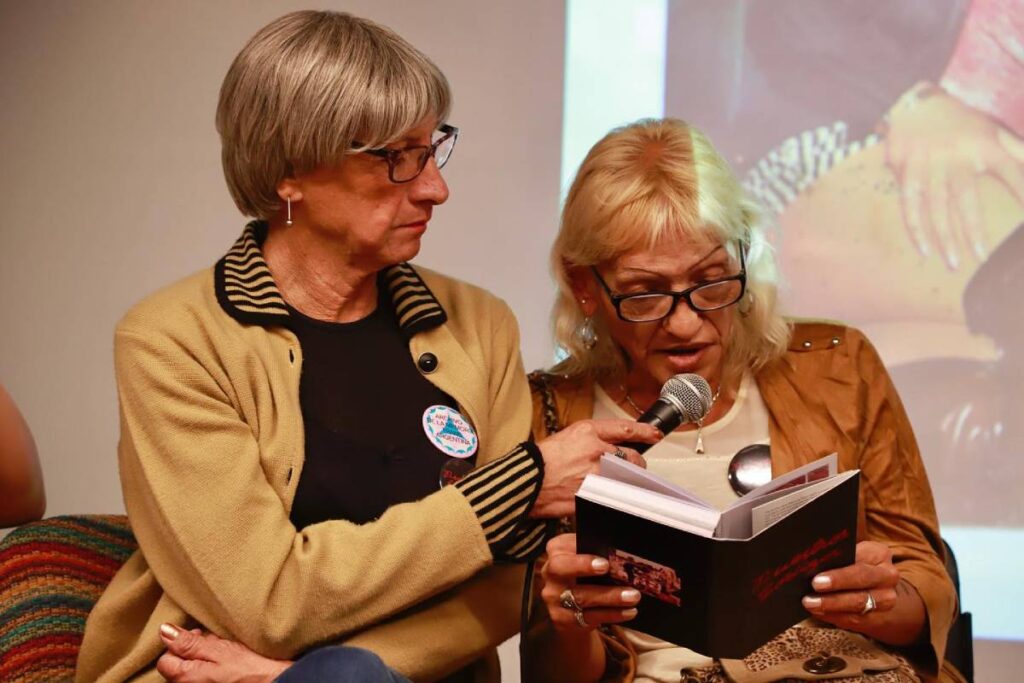

BUENOS AIRES, Argentina. Our Codes is the third book published by the Argentine Trans Memory Archive . Photos and stories are awakened through visual memory, and “could not emerge through any other journalistic technique,” says editor Liliana Viola, proud to have been invited to lead the AMT’s new venture.

The first book was Archivo de la Memoria Trans (Archive of Trans Memory ). It was named after the institution that was being presented to society, and it's like clouds of memories, organized around thematic axes; the second book is Si te viera tu madre (If Your Mother Saw You) , which highlights the vision of Claudia Pía Baudracco and the protagonists who documented their era, with brilliance and struggle.

The collection is organized into four chapters that engage in dialogue with documents from other archives. It invites critical reflection on the 40 years of democracy that were celebrated in Argentina in 2023.

Democracy that wasn't for everyone

“The problem is that there weren’t 40 years of democracy,” states editor Liliana Viola. “Not for us,” agrees María Belén Correa, founder of AMT. “Democracy for us arrived in 2012, with the Gender Identity Law : when the State stopped persecuting us and recognized our identity. In an Argentina where the search for identity is so strong,” she points out, referring to the struggle waged by the Grandmothers of Plaza de Mayo to recover the grandchildren appropriated during the last civic-military dictatorship (1976-1983).

“From 2012 onwards, public policy stopped focusing on how they were going to persecute us, and we began to think about how to get involved in other public policies. What is a dictatorship? When the State persecutes a specific population. That's what they did, a direct genocide against us,” Correa points out.

The late arrival of democracy also meant that it wasn't until 2022 that five trans women and transvestites testified for the first time as surviving victims of state terrorism during the last civic-military dictatorship in Argentina, which took place between 1976 and 1983. They gave their testimony before the Federal Oral Court (TOF) 1 of La Plata on the 101st day of the trial for crimes perpetrated in the brigades of the southern suburbs of Buenos Aires province, known as the Brigadas case.

From police edicts to contravention codes

For a political system to be considered democratic, it is not enough to simply hold elections every two years. Democracy, as government by the people, remains an incomplete project as long as there are groups whose rights are not guaranteed.

The last two chapters of the book discuss codes that are not "ours," as the title suggests, the codes of the community itself. Instead, they address the codes of state persecution. In the chapters titled "The Endless Persecution" and "The Longest Wake in the World," black and white photographs published in the media—mostly sensationalist outlets—appear, depicting transvestites and trans women as victims: dead, imprisoned, being dragged to jail cells.

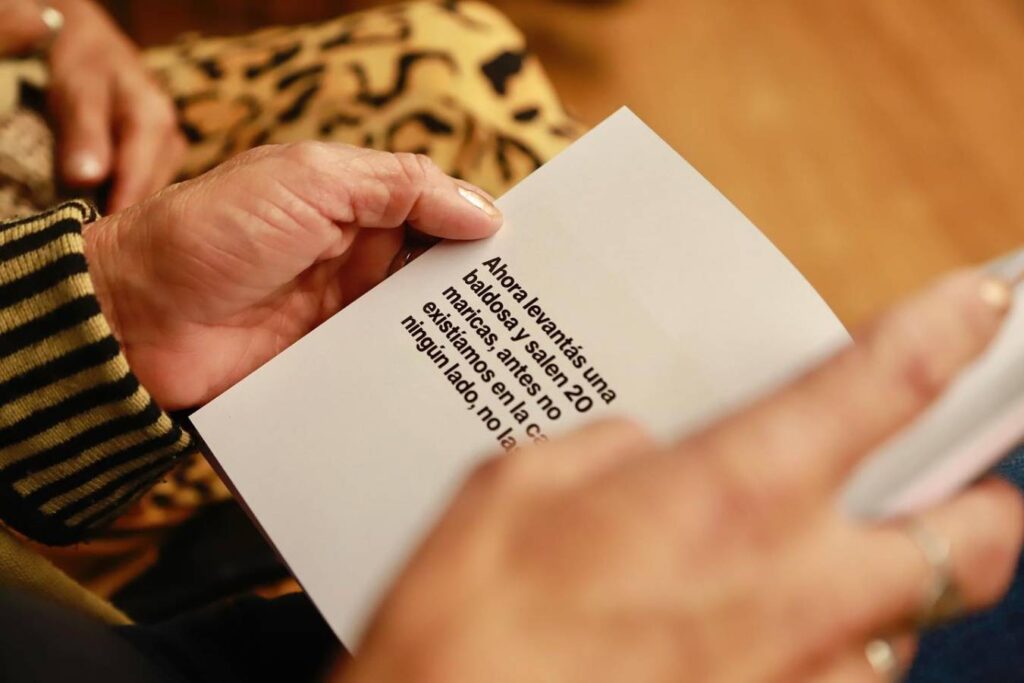

“The policies that the democratic state had for us were ones of persecution. They only changed the names: we overturned the police edicts and they invented new codes of conduct,” María Belén lashes out.

In 1983, the edicts, most of which had been issued by heads of the Federal Police and legitimized through decrees and laws in 1932 and 1947, were still fully in effect. They did not refer to specific acts or behaviors, but rather condemned characteristics or traits of groups of people based on their social status and sexual orientation. The entire procedure for applying these regulations was the responsibility of the police agency: arrest, evidence gathering, and trial. There was no right to a defense, nor any guarantees in the proceedings. Thus, mass and arbitrary arrests were “legalized.”.

The edicts came under debate starting in 1996, with the establishment of the City of Buenos Aires. But in the public debate, urban security was intertwined with a stale, bourgeois moralizing, upheld by the political establishment. The battle was also cultural. In 1998, the edicts were repealed in the City of Buenos Aires, and the trap was simply renamed: the Contravention Codes gave judicial authorities jurisdiction, with similar results. In the province of Buenos Aires, the edicts remained in effect until 2008.

To resist is to win

The published documents also state that transvestite and trans collectives were protagonists of a courageous resistance against this repressive power.

María Belén recalls a memory that illustrates the power of this resistance. After the edicts, the City government built a kind of “waiting room,” because according to the new regulations, trans women could no longer be held in cells. The place had a television mounted on the wall, Venetian blinds, glass partitions, and loose chairs. The day this “waiting” space was inaugurated, 15 women, who weren't supposed to be detained, entered and absolutely destroyed everything.

“That destruction seems memorable to me. They left nothing standing. That was what they had planned for us: they couldn't arrest us, we weren't going to be in a cell, but they were stealing hours from our lives. They kept stealing hours because we had to spend the whole night in that waiting room.”.

Political persecution in the 80s and 90s

“According to our research in official sources, such as the National Library's archives, the largest recorded massacre began in 1984. In 1988, they dissolved the Transvestite Front, a group that included the women from Panamericana. Those who survived were the ones who went into exile. They even killed Mónica Ramos , who was the leader, the head, of that group. This massacre only ended in '89/'90, when they were still carrying out raids on gay nightclubs, like when they arrested Carlos Jaúregui. The first marches were in '92, denouncing these raids in which people were arrested. In transvestite areas, they were simply murdered,” María Belén recounts.

“From that point we say that there was no real democracy since 1983, but rather the biggest massacre came, which was reported in the press, in police cases, in tabloid newspapers. In the 1990s, news reports showed how they dragged girls away to take them inside, to prison.”.

To safeguard democracy, it is essential to integrate into the national memory the reality of those groups of citizens who lacked laws and codes to protect their integrity and rights, warns Liliana Viola. Correa, for her part, emphasizes that when democracy arrived on December 10, 1983, and [the security forces] could no longer enter homes to kidnap students, workers, or teachers, they dedicated themselves to another form of “social cleansing” and established a “morality division” within the Argentine Federal Police. “They used the same green Ford Falcons to arrest young women,” she asserts.

Because of all this persecution, in Argentina transvestite and trans people over 40 years of age are considered "survivors," and there is a significant consensus regarding the need to implement a reparative pension to guarantee a minimum level of access to rights.

The own codes

“Despite what we just discussed, this book is a happy book: it’s a book of pain, but not of tears. Because the codes that appear in the first and second parts are part of a transvestite idiosyncrasy. A way of surviving and a way of building families, which form these codes in opposition to those that will appear in chapters three and four, the codes of others, the codes of contravention,” Viola emphasizes.

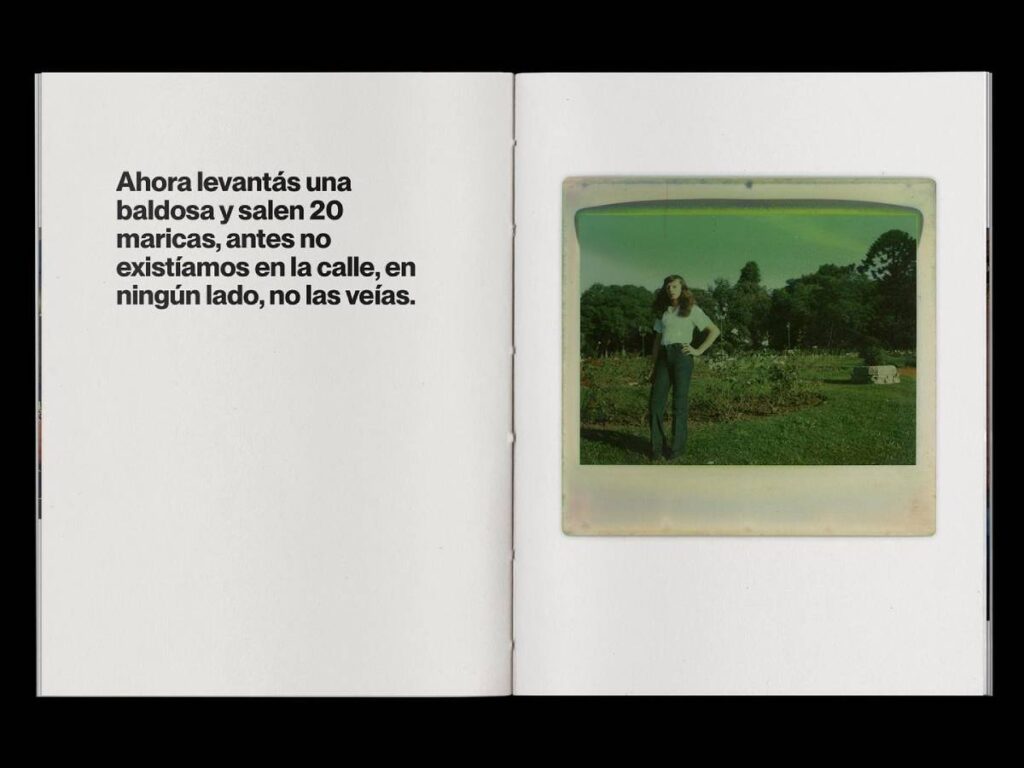

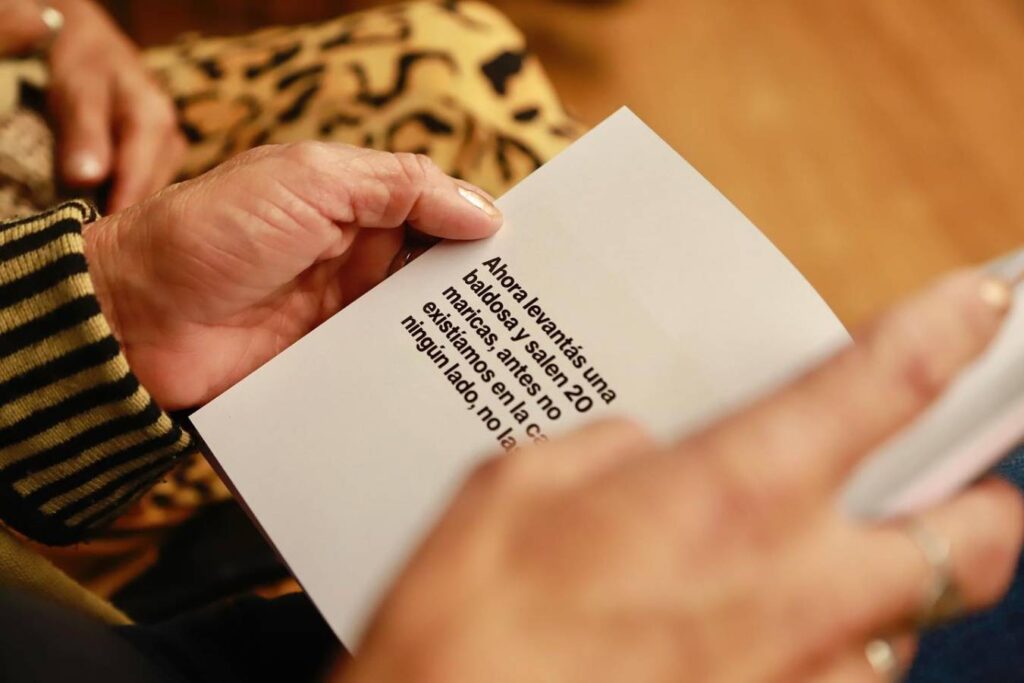

The first chapter is called "Famous Quotes".

The AMT consists of an oral archive, with testimonies recorded by the women themselves. In “all that mass of testimonies,” which spans more than 300 pages, certain phrases are repeated. For example:

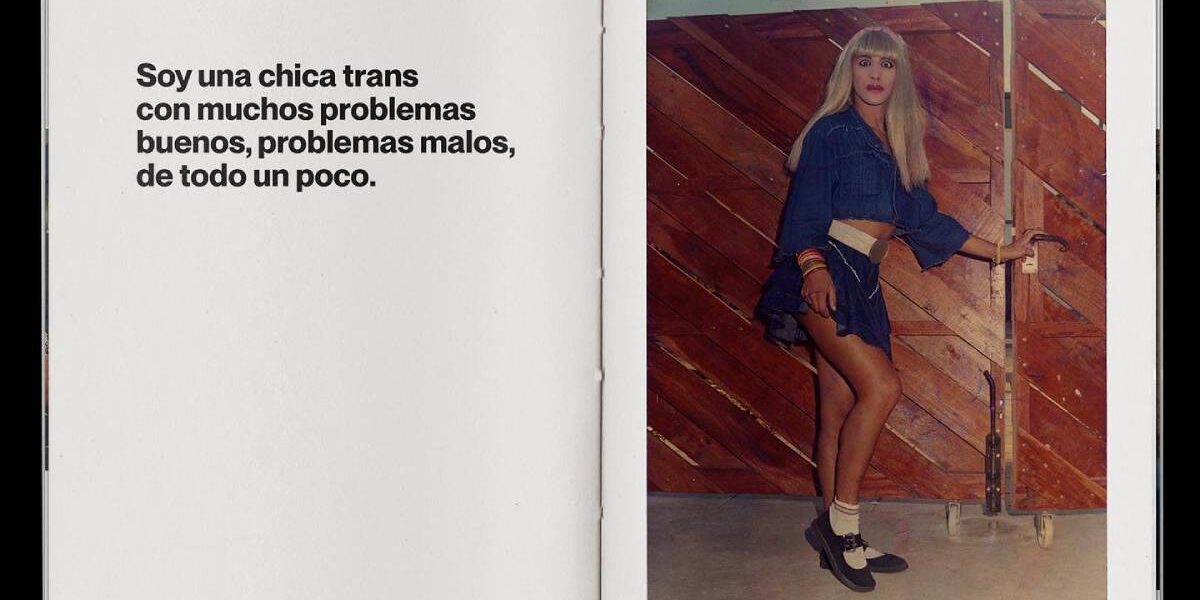

“I’m a trans girl with lots of good problems, bad problems, a little bit of everything.”

“The greatest achievement of my life was doing what I wanted.”.

“At 9 years old I already wanted to wear heels, panties, and a bra. And at 12 I started cross-dressing. But I've always been a woman of character, so it wasn't complicated for me.”.

Archival science

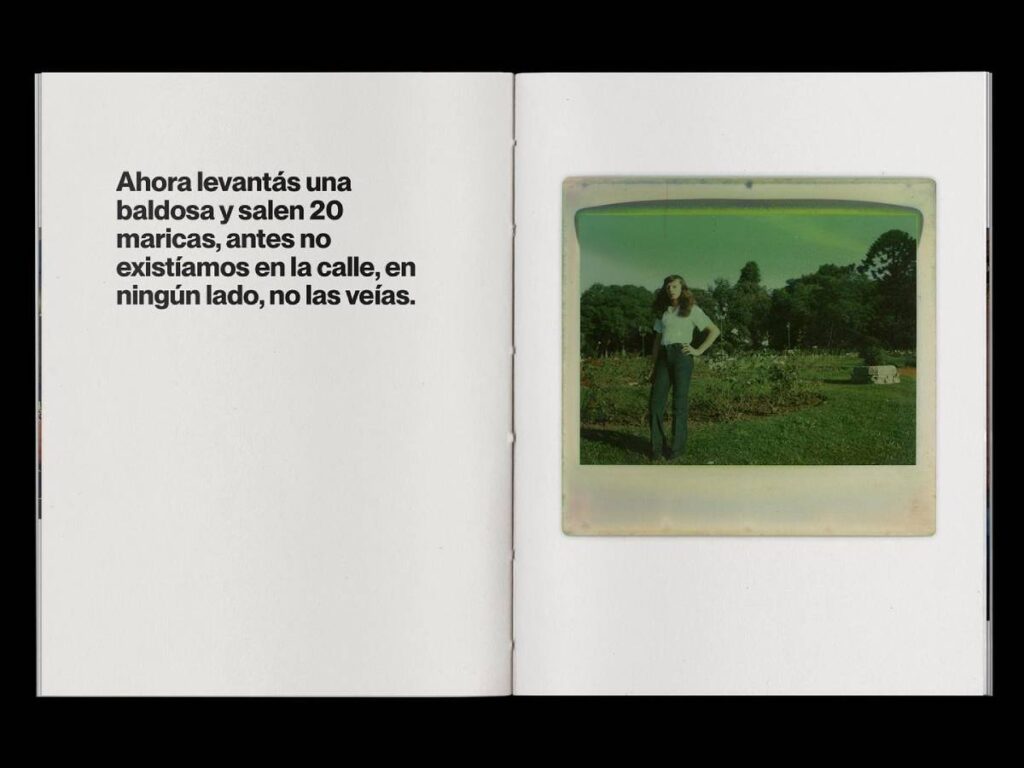

There are many photos taken at parties and gatherings, indoors, "where we can be in groups of more than three." The outdoors is featured in tourist photos from exile, with the Eiffel Tower or the Roman Colosseum in the background. Also in carnivals and picnics.

At the ATM, the pieces were initially cataloged by theme. Now, with over 15,000 photographs and more than 300 pages of transcribed testimonies, they are adapting to the format of the General Archive of the Nation , so that the material can be used in a common language with other archives around the world. Each collection bears the name of the donor.

“The first pink book was a cloud of memories. This third book shows growth and formally names each piece in each collection,” María Belén observes. Furthermore, the short stories accompanying the images capture the way of speaking: the voice remembers and (re)cognizes an identity that is both singular and collective.

At the end, the names of all the people who testified, recognized as authors, appear. In general, they are all alive, with their ages (which today are between 50 and 80 years old), and their current situation.

Free and healthy bodies

The idea of a woman of character, who breaks what she has to break, who doesn't let herself be beaten down, that's all over the book.

Coccinelle had had surgery : 'That's what I want for myself!' I said, and I achieved it, but with a lot of sacrifice,” says another famous quote.

Highlighting the contradiction, behind that page appears another that says: “I take this opportunity to tell you not to get silicone implants, it’s the worst thing I could have ever done. That’s a little piece of advice. Nothing more.”.

Regarding this issue, María Belén wrote an article in Diario.ar about the death of Argentine model Silvina Luna, a victim of malpractice during a cosmetic procedure. In her column, she reflects on societal expectations, the risks and consequences of silicone implants, and calls on the government to ensure that the healthcare system addresses the problems associated with this often-silenced abuse.

Towards a real democracy

“It wasn’t until 2012 that we began to build a democracy for ourselves,” they repeat, as a starting point. And they draw a parallel with feminism in the 1980s: “I think it’s like when feminism began to fill its first jobs, and those were only as secretaries, and it seemed like they would never hold positions of power. I think we’re at that stage now. There are some female civil servants. There are some who can go to school. There are some who can keep their jobs, and they aren’t fired if they transition. We’re at the beginning,” Correa explains, adding to and multiplying their rights.

The calculation is eternalized in the book-object being presented, with excellent print quality, with a matte finish that allows you to appreciate infinite shades of light and shadow.

It can be purchased at the following link: https://archivotrans.empretienda.com.ar/libro/nuestros-codigos

Photos : Facebook-Trans Memory Archive

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.