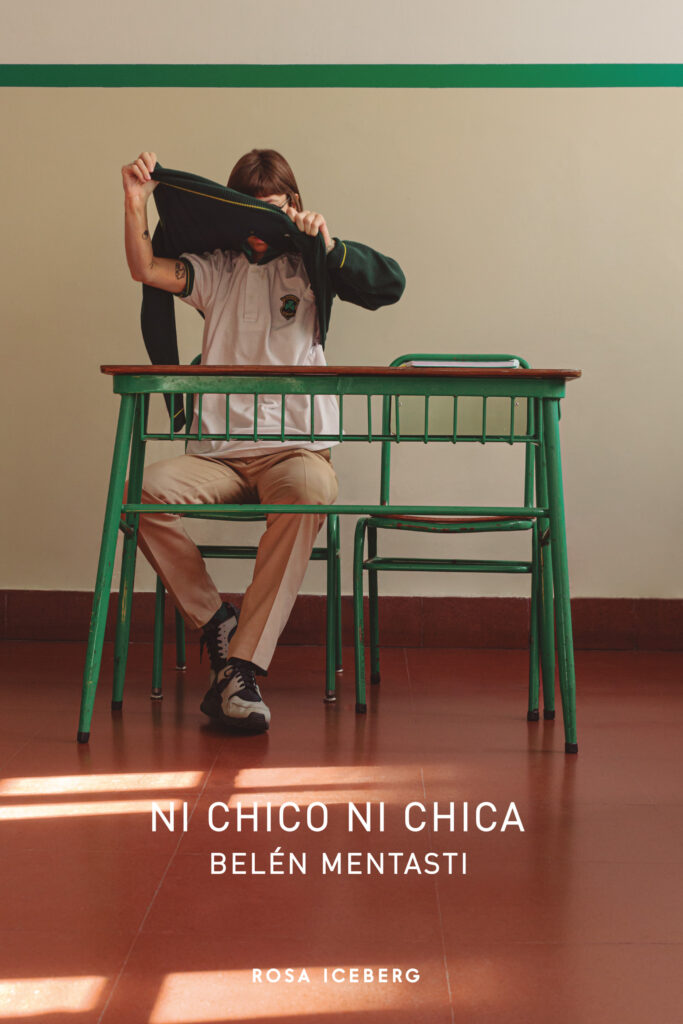

Neither Boy Nor Girl, a novel about becoming a teenager and queer in 1990s Argentina

With precision and sensitivity, Belén Mentasti's literary debut transports us to the intimacy of a teenager who defies gender norms and questions her identity.

Share

“Dr. Pirrelli, that was his name, palpated my budding breasts. I hadn’t been scared until I was there, in the silence he created after touching me until he declared: it’s almost normal .” This scene from the book Neither Boy Nor Girl, the latest release from Rosa Iceberg publishing house, could summarize the tone of Belén Mentasti’s first novel.

This is a coming-of-age story in which Malena, a protagonist experiencing her adolescence in the late 1990s, discovers almost everything for the first time: she smokes her first cigarette, falls in love with a teacher, breaks up with her best friend, runs away from home, dresses as a boy, and is dragged by her mother to a gynecological appointment. And she discovers that, in the eyes of traditional medicine, she is "almost normal."

And Malena, at just sixteen years old, seemed to understand what Néstor Perlongher said ad nauseam: there is no being and non-being, there is becoming . “She is not unhappy with her sexual variation, she is fine with it, but it is society, through the voice of this gynecologist who presents himself as a kind of 'villain', that judges her,” the author explains.

Belén Mentasti is 33 years old and says she discovered literature relatively recently. Despite her late arrival to the literary world, she has already received numerous awards: her short story "Un re amague" was selected for the Biennial of Young Art, and she received a Creation Grant from the National Arts Fund to write * Ni chico ni chica* (Neither Boy Nor Girl) . She trained in writing workshops with Gabriela Cabezón Cámara and Romina Paula , and edited this work with Marina Yuszczuk. Belén also trained in playwriting in workshops led by Mauricio Kartún and Ignacio Apolo. In 2018, she premiered the play * Si fueras varón, ¿gustarías de mí?* (If You Were a Man, Would You Like Me?) at Microteatro. In 2019, she directed and wrote a short film called *Algo Tenía* (I Had Something), which was selected for various festivals, such as FIDBA, FICCE, the Gaze Festival (Ireland), and the Lustsreifen Film Festival (Switzerland).

Writing from diversity in a binary world

It's no easy task to construct a teenage universe with both rawness and tenderness, without judgment or romanticization. The idea for this project by Belén Mentasti arose in the workshop of writer Gabriela Cabezón Cámara, and all her doubts passed through that space. For an entire year, a group of women—and just as many cats and dogs—met at her home in San Telmo to read and share a different vision of the world.

“When I brought the idea for this novel to her, Gabi told me, ‘Just go for it.’ I didn’t know where that ‘forward’ was, but she trusted me, and that intuition helped me a lot,” the author recounts. Then came the pandemic, the workshop went virtual, the groups changed, and that’s how she met the writer and teacher Lía Chara. “She taught me to name things less, to create tension between what is said and what is revealed, which is something she does brilliantly.”.

In all those literary gatherings, alongside teachers and classmates, Belén raised the question of inclusive language in literature. Part of her wanted to write this story using non-binary language, one that was true to her current beliefs, but she ultimately abandoned the idea. Inclusive language wasn't an option for this novel, which, above all, had to reflect the reality of that time. The decision was so firm that, in the book, she emphasizes the masculine as an exclusionary language: through addressing "friends," "comrades," and "students," she reflects a world that only makes cismasculine identities visible.

“In the early 2000s, binary culture was very strong. Ambiguity, not defining oneself as feminine or masculine, was something that made people very uncomfortable. In this book, I'm interested in exploring how someone who experiences that discomfort speaks from their perspective,” Belén explains.

The classroom and literature, territories for LGBTIA+ disputes

When she was little, Belén was always on the verge of being expelled from school. She misbehaved, but she sensed there was a reason behind her discomfort. The institution bothered her, the silence surrounding certain things, the imposed limits. “Childhoods have something very genuine about them, and I wasn't comfortable with those rules. My school was supposedly atheist, but they made us go on spiritual retreats, and I didn't really understand why. By the time I was 10, I was fed up with the world, and nobody explained anything to me, so I misbehaved to get expelled, and I reached the limit of absences.”.

And then, in a class about flower reproduction, a biology teacher explains something about water lilies. “They are plants that have the male (stamens) and female (pistil) reproductive organs in the same flower.” A teenage girl in the classroom is stunned. “The character of Professor Caferata is inspired by one of my teachers from school. She was the typical lesbian, although back then it wasn't something people talked about or named. She dressed in a shirt buttoned all the way up, baggy pants—she was completely masculine—and even through her silence, she commanded respect. In those days, her mere presence spoke volumes.”

Yahoo Answers

“This thing I had with my teacher, this certain mystery that I couldn't quite grasp about what was happening to me with my sexuality, sparked a lot of curiosity in me. And literature brought me some answers and possible worlds.” That's how the character of Caferata, the biology teacher as a metaphor, came about: “She wrote the word 'anomaly' at the bottom. Then, a colon: 'They're inverted flowers.' That day I learned that figs weren't fruits but flowers that grew inwards, and that male figs weren't edible, but female ones were.”

Malena's character, then, goes into an internet café and searches Yahoo Answers for "my period, what's wrong, why do I have this abnormality?" because she needs answers. And, in a similar move to her protagonist, she confesses that literature was the refuge where she often sought answers. "I think that sometimes, these other ways of naming things, like writing, have to do with explaining things to those around us, or in my case, to my family. No one is obligated to do it, no one has to explain anything to their relatives, but when I came out as a lesbian, I was asked a lot of questions, I was challenged, and these are possible answers," Belén explains. Later, she would discover that books don't provide answers, but they do open up possible worlds. "And in those worlds, sometimes, things can be a little better."

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.