The first Dissident Memory Archive is created in Peru

A group of activists set out to recover LGBT+ history. A political stance against invisibility.

Share

By Verónica Ferrari

Photos: Dissident Memory Archive

LIMA, Peru. The history of the LGBTQ+ community in Peru is not easy to find. Few people have taken the time to systematize, archive, preserve, or recover the memory of a population that continues to be ignored by the Peruvian government. This is especially true given the conservative drift that began with the administration of Dina Boluarte.

Historical, academic, and human rights essays abound. But what about what the press said, or the testimonies of LGBTQ+ people themselves? What about their photographs, or the traces of their lives? What about their art and their transgressions in both private and public spheres? Who rescues their memory? And not only that, but who keeps it alive so that others can hear it and learn about it, so that others can see themselves reflected in it and continue to resist?

Every archive is political. What is preserved and what is lost involves a decision of survival or disappearance, and for a long time the priority of the Peruvian state was to make the LGBTQ+ population disappear. Not only through the shortage of medicines to treat HIV, the persecution, raids, and arrests in gay clubs, or the constant denial of their lives in norms, public policies, and human rights plans, but also through silence, omission, and forgetting.

That is why archives rise up to speak out against the silence, to act instead of omitting, to remember and cease forgetting. Ronny Álvarez, Ana Karina Barandiarán, and I are committed to this endeavor: finding a place to preserve the history of the forgotten. That place is now called the Archive of Dissident Memory and is located in a house in downtown Lima, open to anyone who wants to learn more about this story.

From book to archive

Álvarez tells us how the idea for the archive was born: “It arises due to the non-existence of an archive of the LGTBIQ+ memory in Peru, to which is added a systematic and structural policy of erasure by the Peruvian State and its public institutions.

This has definitely had an impact on society. We could say that the seed that sparked the idea was the Bicentennial celebration, since when preparing some milestones on LGBTQ+ experiences, we were surprised to find that there was no archive of any kind that preserved our records .

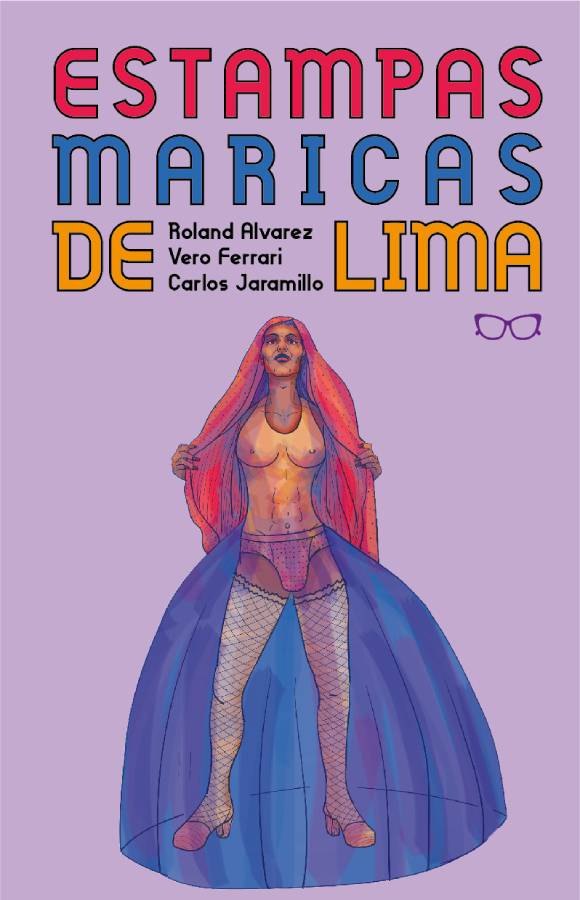

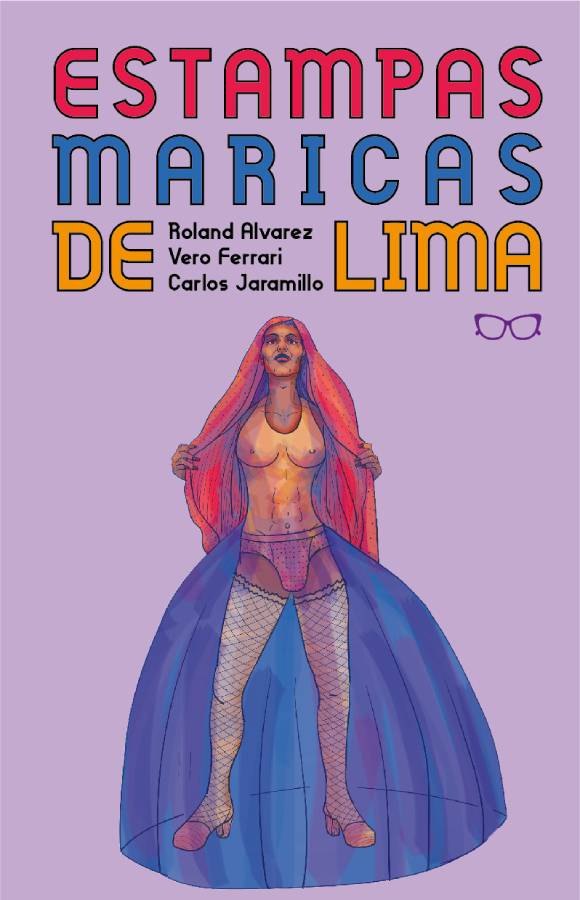

These milestones became * Estampas maricas* (Queer Sketches ), a collection of illustrated stories written collaboratively by Álvarez, Ferrari, and Carlos Jaramillo, which reclaim the LGBTQ+ history of republican Lima. Published in 2023 by Gafas Moradas , the book fictionalizes various Peruvian historical episodes from the 19th and 20th centuries. It also includes a story based on the pre-Hispanic Moche culture.

The authors reclaim a despised and denied past and reinscribe it into history, reclaiming the space it deserves. The ten vignettes that make up the book constitute an arduous work of (re)construction based on the search for material evidence about the experiences and lives of diverse individuals.

As the book's introduction states: “ Queer Images of Lima opposes the invisibility and denial of sexual dissidence in our history, reaffirming that it has always existed. The book reveals an undeniable truth: diversity has always been part of our history. This recovery, rescue, and (re)construction of the ‘queer/butch/transvestite’ past seeks to reaffirm the present and illuminate the future of the Peruvian LGBTQ+ community, which is, was, and always will be.”

A void in history

But what exactly does the work done in the archive entail? Barandiarán tells us from Spain, -where she is studying for a master's degree in documentary archives- that this archive consists of recovering experiences and evidence of LGBTQ+ existence, mainly through photographs, testimonies and audiovisual material.

Aside from their extensive collection of books, research, studies, posters, postcards, and newspaper clippings that document decades of dissident history, “There is a huge void that we, as civil society, must fill, especially regarding lesbian and trans histories. These stories are lost through oral tradition, passed from mouth to mouth, and only known to a select few. Or, when someone dies and the family disposes of or burns their belongings, their stories are suddenly erased. We want these lives to be preserved and for everyone to know them.”

Álvarez adds that “the archive is an open invitation for everyone who wants to share their experiences .” She also knows that the best work is done door-to-door, so the archive travels to different regions to recover those everyday experiences that have been “invisible” and which are showcased on the Facebook page and Instagram platform.

The archive is maintained solely through the self-management of its founders in a country that rarely supports populations like the LGBTQ+ community. But it was high time to start recovering this history, not only in Lima, but throughout Peru. That's why they hope more initiatives like this will emerge, where the history of all Peruvians can be found in physical spaces, within filing cabinets.

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.