“In this house, faggots live together”: LGBTIQ+ resistance spaces in El Salvador

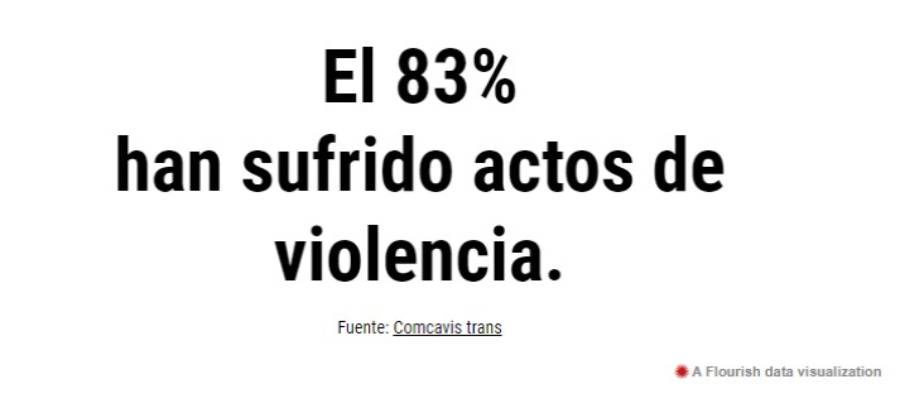

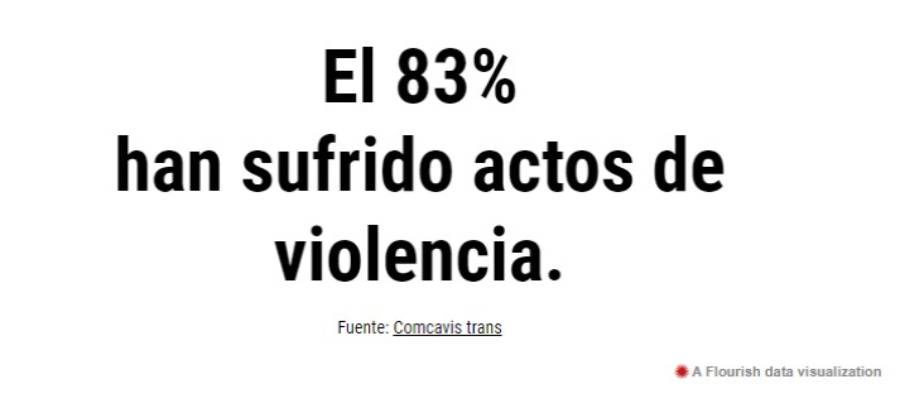

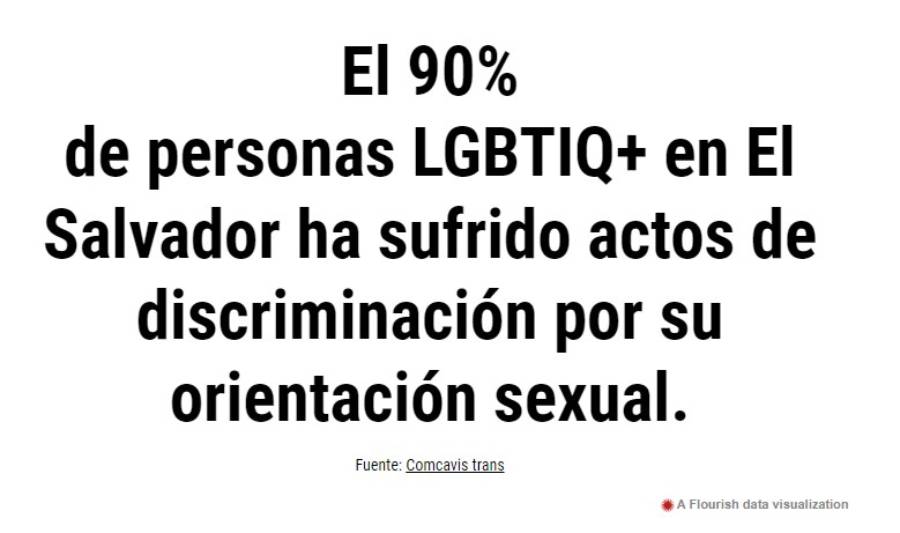

Luis, Karina, and Carlos are part of the LGBTIQ+ community in El Salvador. They come from different backgrounds, but they have something in common: they have suffered violence, discrimination, and inequality because of their sexual orientation. They have also found ways to fight and resist the abuses of individuals and a state that ignores their needs: social organization in dissident collectives.

Share

The sign adorns the entrance of Casa Flamenco, a restaurant in the municipality of Suchitoto, in Cuscatlán, El Salvador. “In this house, faggots live together,” it reads in black letters against a rainbow background.

That small act of everyday resistance, of welcoming with a word that has been used to refer to LGBTIQ+ people in a pejorative way, is one of many by the owner, Luis Figueroa.

He is gay and has been involved in the fight for LGBTQ+ rights for years, both in his personal life as an activist and in his professional work as a lawyer for an organization that defends the economic, social, and cultural rights of LGBTQ+ people.

There aren't many places like Casa Flamenco in Suchitoto . It's a small municipality with fewer than 25,000 inhabitants and little visibility of its diverse population.

But Luis knows firsthand the importance of creating safe spaces to counter exclusion, and social movements that embrace diversity in the face of the violence and discrimination experienced by LGBTIQ+ people in all areas, from the home to the workplace.

From denial to pride and organization

Getting to where he is today has been a long journey, and not without obstacles along the way. He grew up in a middle-class home where he never lacked anything. But his family was very religious and did not accept LGBTQ+ people. Being gay was not only frowned upon, but considered a sin.

Luis knew from the age of six that he liked boys, but he hid it throughout his childhood and adolescence. He was afraid that his sexual orientation would hurt his loved ones.

“I saw my grandmother worried that I was going to come out as gay, so I made a promise: I was going to hide my sexual orientation as much as possible so as not to cause her any harm,” says Luis.

He also hid to protect himself from being bullied at the private school, Cristóbal Colón, where he studied. He avoided any contact with other teenagers and isolated himself. He avoided expressions or interactions that could have sexual connotations. He had no friends, played alone, and didn't participate in sports. He compensated for his lack of affection with his good academic performance.

“During my adolescence, I was absolutely inhibited from doing anything because that would have meant exposing myself. It was a real fear; I saw examples of my classmates with a more feminine gender expression suffering harassment and aggression,” he recalls.

Hiding a part of himself to fit in and avoid violence at school had consequences. It led him to deny his sexual orientation. He even began seeking ways to 'change,' including so-called 'conversion therapies,' and traveled to a church in Guatemala hoping that, through prayer, he could be "cured of his condition."

Much has changed since then. In his 20s, he came out to his friends and his mother, the only person in his family whose acceptance mattered to Luis. And contrary to his fears, he found no rejection, only support and love.

His job was different. It was a state institution, and coming out as gay had such negative consequences that he ended up resigning.

“Living my sexuality and sexual orientation openly was a death sentence for my career advancement at my workplace. I heard that publicizing my sexual orientation was something I should keep private. That meant I wasn't going to get ahead in that institution,” she shares.

In the social movement, she found a battleground precisely to fight against this type of discrimination and to defend the rights of diverse people. She began her activism based on her own experiences.

“Everything I have learned from the fight for diversity rights has been thanks to the social movement,” says Luis.

For Luis, working to defend human rights has allowed him to defend his own. Like in 2016, when he participated in a lawsuit filed with the Supreme Court of Justice seeking the legalization of same-sex marriage in El Salvador.

Seven years later, in 2022, when Luis and his partner Rolando decided to get married, they had to travel to San José, Costa Rica to access what is a guaranteed right for any other couple because it remains impossible in their country.

She acknowledges that she enjoys privileges that most LGBTIQ+ people in El Salvador do not have, and that this contributes to their vulnerability and exposure to structural violence. This inequality only further reinforces the importance of the role of social organizations.

Social organization to confront violence

The LGBTIQ+ population in Suchitoto is not recognized and is made invisible, says Andreina Guillén, representative of the organization Huellas de Suchitoto, the only LGBTIQ+ organization in the municipality.

The collective was born from the initiative of a diverse group of people who felt the need for a safe space to talk about the violence affecting them and to seek solutions. They assert that if discrimination didn't exist in Suchitoto, it would increase significantly.

“From what we’ve discussed with young people, they’re still shocked when they see a gay person, a lesbian, or a transgender person. So, we need to do a lot of work on the issue of diversity so that people become more aware and, at the very least, begin to accept and respect diversity,” Guillén emphasizes.

In 2020, “Huellas de Suchitoto” opened its doors to LGBTQ+ individuals between the ages of 17 and 45 from the municipalities of Suchitoto and San Pedro Perulapán . Despite its short existence, organizing within the collective has already had a positive impact on Carlos Henríquez and 'Karina'.

'Karina' is 38 years old. She is a lesbian, a feminist, a social communicator, and has been a human rights defender for women and LGBTQ+ people for 15 years. She tells her story using a pseudonym, so as not to "hurt" her mother because of her sexual orientation.

Being organized has been a way for her to process the violence she has suffered since childhood. She ran away from home at 14, after her sister betrayed her trust and told their mother that Karina was a lesbian.

Karina's mother reacted violently when she found out. She physically and verbally abused her and sent her to a psychologist and a psychiatrist. When her siblings saw her in the street, they shouted insults at her from a distance.

“I thought I was sick, you know, because I liked women,” she says.

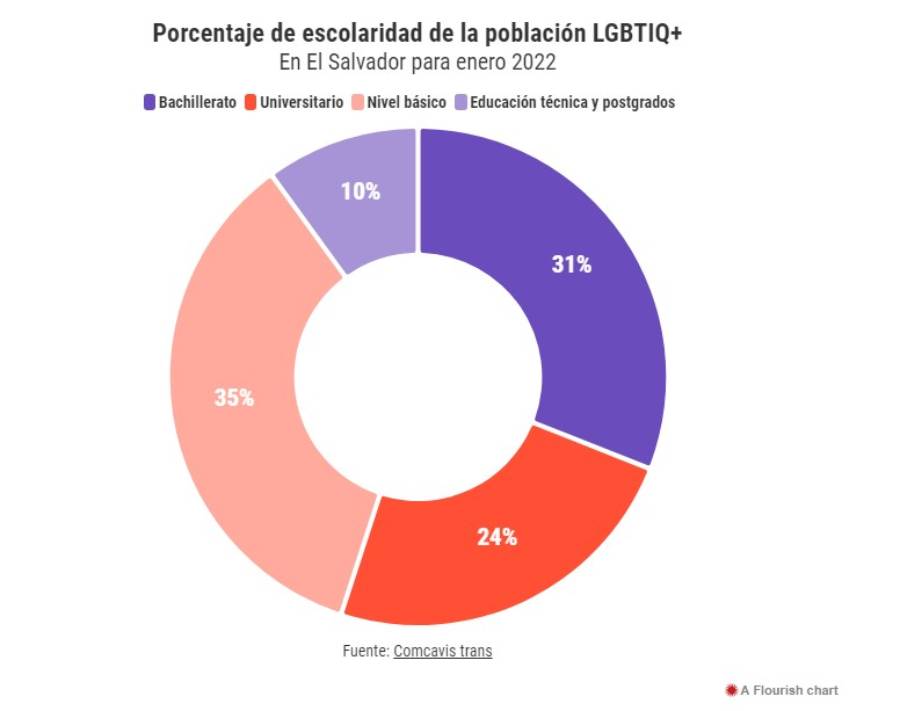

a gay activist and founder of the Salvadoran LGBTI Federation , points out that being expelled from their homes at a young age has repercussions in the school setting. This prevents LGBTQ+ individuals from entering the workforce as adults due to their low levels of education.

This was the case for Karina. Since leaving home, she stopped studying because she started working to pay for food and a roof over her head.

“Belonging to the LGBTI community in a country that doesn’t even respect your decision and autonomy over your body is very difficult; we don’t even exist. I mean, there are no guaranteed rights, adding to that all the levels of discrimination that exist,” she emphasizes.

Fifteen years ago, Karina was embraced by the social organization. She learned to openly identify as a lesbian woman, without shame. Since then, she has participated in women's projects, HIV prevention initiatives, and sexual and reproductive rights programs, and she played a key role in the approval of the National Youth Policy. She aspires to support other girls who are discovering their sexual orientation.

“First, women’s organizations taught me that violence existed; second, to recognize that violence; and third, to accept that I had experienced all forms of violence. Now, I am fortunate to say publicly: I am a lesbian woman, and being organized has been my salvation,” says Karina.

The traces of a dissident history

As a child, growing up in a rural area of the municipality of San Pedro Perulapán, in the Istagua canton, Carlos Henríquez dreamed of studying nursing. But like Karina, discrimination for being an LGBTQ+ person ultimately kept him away from the education system.

He attended a public school where he was the victim of bullying and severe discrimination for being gay. It culminated when the school's marching band instructor learned of Carlos's sexual orientation. A classmate called him to alert him.

“He told everyone they had to beat me up. Oh, that’s why I never went back to school. He called me the day it was going to happen, and I never went back,” Carlos says sadly. He was only 17 years old and passionate about music.

“I dropped out of school because of fear, but you learn to live with it, or you ignore it,” she says. Twelve years passed before she was able to resume and finish high school, under a flexible study program.

She was struck by the fact that, as teenagers in the public education system, students did not receive comprehensive sexuality education. Nor was it something she discussed with her friends or family.

Now, at 35, the harassment and verbal abuse still haunt her in her adult life. When she visits the town hall, she is harassed by security guards. She also experiences harassment on the streets and in hospitals.

“People are still not aware of it,” he explains.

She has been part of “Huellas de Suchitoto” for two years. The impact on her life has been remarkable. She received psychological support and workshops on the prevention of violence and sexually transmitted infections.

She feels that her self-esteem and self-confidence have grown, and now she attends LGBTIQ+ marches in dresses, which has always been part of her gender expression.

Empowering people to not be afraid to identify as diverse individuals was one of the goals of founding “Huellas de Suchitoto.” It has contributed to making the LGBTIQ+ community in the municipality more visible and demanding recognition of their rights.

“The first thing organizations do is work with them, support them in gaining recognition, inform them about the laws, and strengthen their personal and collective empowerment so they can make more assertive decisions. These collectives do a good job. They focus on providing psychological and clinical care related to sexual and reproductive health,” says Guillén.

Progress or setbacks?

In September 2022, the Ministry of Education (Mined) removed the educational program "Aprendamos en Casa" (Let's Learn at Home). The program, which addressed topics related to sex education, was broadcast on Channel 10. In a press release, Mined reported that Carlos Rodríguez Rivas, director of the Teacher Training Institute that produced the program, was removed from his position for disseminating "unauthorized sexual content."

This is just one of the measures taken during President Naib Bukele's administration that weakens sexual and reproductive rights, as well as those of the LGBTIQ+ population. The Secretariat of Social Inclusion, the agency in charge of the Directorate of Sexual Diversity, was also suspended, and the Ministry of Education removed comprehensive sexuality education programs from the school curriculum.

Guillén explains that the diverse population faces a scenario that points towards setbacks in terms of human rights.

“It’s a step backward because this means that education will be more biased,” Guillén laments.

It fosters greater inequality and exclusion in a context where diverse people already live under constant discrimination.

“We have a society that, in general terms, is homophobic and violent. But in particular terms, this violence also manifests itself more congruently when people suffer exclusion due to poverty, lack of education, access to health, and so on,” emphasizes Erick Ortiz.

Faced with this void, LGBTIQ+ groups assume responsibilities that belong to the State: ensuring a life free from discrimination, inequalities and violence towards diverse people and guaranteeing respect for their human rights.

According to Ortiz, the Salvadoran State is unable to respond to the needs of this population because it is not even interested in knowing the reality.

“The reality is that the government has systematically dismantled any existing channels of communication. If it had a different vision for its political project, it could take advantage of all the work accumulated by social organizations. I believe that the Salvadoran state is currently incapable of addressing the reality of LGBTI people simply because it has neither eyes nor ears to listen,” the advocate points out.

Resist

In case any doubts remained after crossing the threshold, a chalkboard in the Casa Flamenco lobby details, in inclusive language, that this is a discrimination-free space. And from every corner of this colorful oasis, messages like “love is love,” “resist,” and acceptance of people of all genders, classes, races, sexes, ages, and sexual orientations are repeated.

Having grown up in fear and hiding in his school, Luis Figueroa now lives his sexual orientation fully and actively contributes to and encourages others to be and do the same, largely thanks to his involvement in the social movement.

“We facilitate the conditions so that they too can join the fight,” says Luis.

The story behind his restaurant is one of resistance and vindication. The house belonged to his family.

“That I ended up here, in this house, meant my victory over the most conservative members of the family, who always said that because of my sexual orientation I was condemned to do nothing in life, to offer nothing, and so for me it was about giving new meaning to family and history,”

Luis describes his venture as a transformative business. An initiative that breaks down prejudices and opens new paths.

“Yes, it is possible to participate in economic development while also promoting respect for diversity, impacting the community by being an example of how things can be done,” he says with emotion.

And he continues: “Yes, it is possible to do business in a very Catholic town, putting the LGBTI flag on the door, putting all one's privileges in favor of a struggle in a territory, which hopefully will also serve as an inspiration.”

A sign, an organization, or a restaurant. Reclaiming words, spaces, and existences to redefine them are acts of resistance in a social and political environment that is becoming increasingly hostile to LGBTQ+ people. Meanwhile, Luis, Karina, and Carlos continue fighting from their own realities and through social organizing, defending their rights and the rights of other LGBTQ+ people.

This article was originally published in Alharaca and is republished through an agreement with Agencia Presentes. On the last Wednesday of each month, you can find in Alharaca and Presentes the articles we share to strengthen ties between media outlets with a gender and human rights perspective in Latin America.

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.