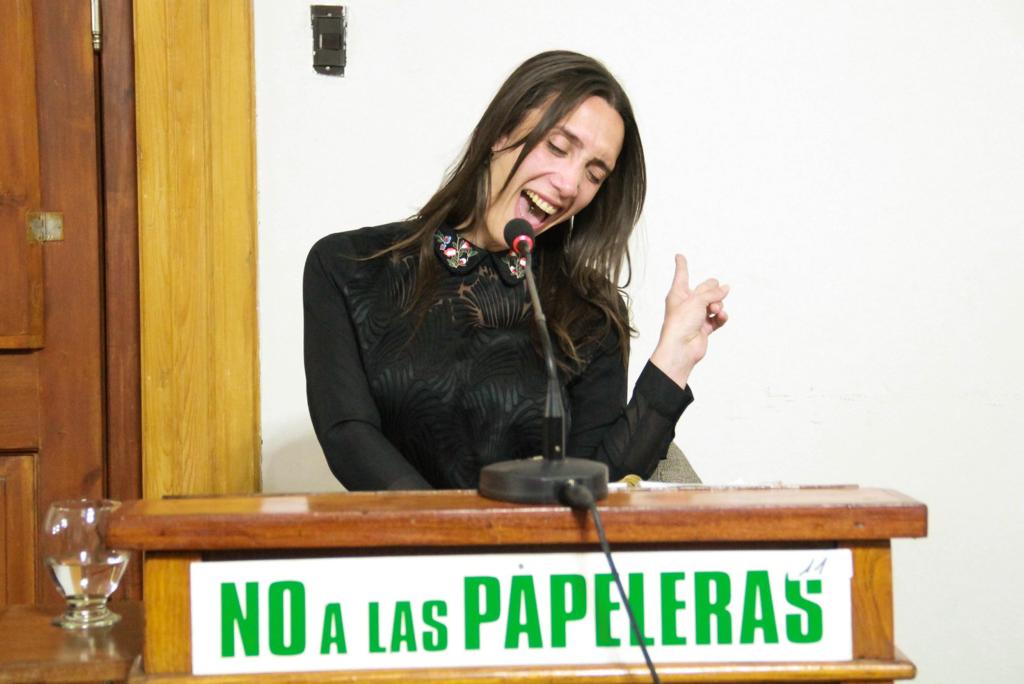

Manu González, trans councilor: “Freedom means more rights”

Manuela González is the first transgender councilwoman in Entre Ríos. Since August, she has held a seat on the Gualeguaychú City Council. A teacher, she also served as the municipality's Director of Diversity. This interview explores her life in school, carnivals, activism, and politics.

Share

“For my dad, for my mom, for my city, for the country I love, for a more just and equal society free from violence and discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender, and for a more just and equitable city for everyone. Yes, I swear.” This is how Manuela González swore upon taking her seat in Gualeguaychú and becoming the first transgender councilwoman in the province of Entre Ríos.

Manu, as everyone calls her, had already distinguished herself in the municipality as director of diversity, a position she held from 2021 until August 8, 2023, when she began her term on the Honorable Deliberative Council of Gualeguaychú. She had also left her mark on public schools as both a student and a teacher. Manu shares stories of constant transitions: from student to teacher, from teacher to activist.

A school that doesn't expel

“To be an activist for the cause, you don’t have to be LGBT+: you just have to be an empathetic person,” she says. She is 35 years old and has a family that has always accepted her. She graduated as a teacher at 22, just one year before the gender identity law was passed in 2012.

At the head of the municipal department, Manu dedicated herself to planning training programs and courses: workshops on the Micaela Law , training for police officers, members of the judiciary, members of the penal unit, doctors, teachers, and courses on LGBT children. The formal Comprehensive Sexuality Education (CSE) , in coordination with the provincial education department, had to be repeated two years in a row because more than 800 teachers enrolled. “We need a school that doesn't expel students,” she emphasizes.

“My colleagues and I always agree that politics needs a lot of education to be able to transform, especially in spaces that have many barriers built from a lack of understanding,” she says. And she posits: “Diversity is learned through coexistence .” She warns that it is necessary to repair the association that relegated trans narratives to the realm of the illegal, through activism with an educational approach.

Family identity

Manu says her mom and dad had her later in life, that they always loved and accepted her, even without knowing what she was, even without being able to name her. She remembers that her father, Jacinto, would applaud her when she danced to Thalía. Manu's dream was to be a fashion designer. But they couldn't afford to send her to university in Buenos Aires.

Her father worked as a bricklayer and her mother as a homemaker. Sometimes she cleaned for other families: a "warrior" of domestic service, as she calls it. "That's the cruelty," she says, "you have dreams and the economic circumstances prevent you from achieving them. But purchasing power never defines you." She emphasizes this with the tone of a teacher who knows the concepts she wants to instill.

She fell in love for the first time at 17, and after a dance she told her mother, a "country" woman, who comforted her by downplaying the matter: "It's not the end of the world, daughter." Her father was getting up, and he was worried by her tears.

"What did they do to you!" he exclaimed at first, but then he sensed that the drama was coming from another direction, and he felt relieved:

— Oh Manu. You're in love with So-and-so — he told her, and he guessed the name correctly.

She remained silent. He added:

— I love you just the way you are, however you want to be, whether you want to be a boy or a girl. I want you to be happy — he hugged her, and Manu says that at that moment 50 kilos were lifted from his shoulders.

“I went through all my phases. I was a sissy. I always had long hair, since I was 12, when I finished elementary school. I was always a very androgynous girl, I don't have body hair. Once I had to go to a psychologist because people were staring at me, looking for the binary,” she says.

Kicking the education system

When she was studying to be a teacher, she was sometimes forced to dress as a boy, with shoes, her hair tied back, and clothes she'd never owned and had to acquire, as if she were going to do a performance. Although she didn't suffer direct aggression, in the academic setting she recalls always experiencing "that stigma that pervades the LGBT community, like being treated as a case study, as if they were looking for something hidden." She completed all her courses and passed them on the first try.

She graduated very young and began to doubt how to practice the teaching profession. “It was like kicking the education system to the curb,” she remarks.

Before attending the public event where she obtained her first teaching hours, she was afraid; she didn't want to go. Her father convinced her: “Go and try it. I see how much people like you on the street.” Her uncle Guille took her by motorcycle to School Number 4 Gervasio Méndez, with more than 500 students, an elite public school, where, based on merit, she had been assigned the sixth-grade substitute position.

“It was a place no transvestite had ever been, or someone with such a feminine identity as mine, who didn't have breasts at the time, but wasn't gay, I was a queer woman, very feminine,” she recalls. In the hall, her nerves returned. She was about to leave when she ran into Rosita, another teacher with whom she had done her residency the previous year.

—Manu! What are you doing here? Did you get a job?

—Yes, but I'm not up for it, this isn't for me.

— How can you not be excited? You're excellent! Come with me— he said and took her by the hand to the office, introduced her to her classmates, and when the bell rang she had no choice but to go to the sixth grade classroom.

At the end of the year, she was in charge of the graduation party and received a huge bouquet of flowers from the families of her students. Only then did she feel relieved: “I understood that this was my place, and that who I was wasn't an impediment to working with these kids. And this is also a public school,” she emphasizes.

The privilege of a transvestite teacher

She herself says that her transition “happened in the classroom.” “At that time, I didn’t have an ID (with the gender change) because I wasn’t interested; I felt it didn’t define me. I was always Manu. But one day I had to have surgery, and when I went to the hospital, they called me by male names. It made me uncomfortable. I got breast implants and then the ID. One day I had to talk to my students; I wanted them to hear it from me. And it was completely normal.”

— Not everyone has the privilege of having a transvestite teacher — she told them.

Quimey Ramos's story went viral , stemming from her transition in the classroom, they got in touch. Quimey invited Manu to a meeting of trans teachers at the Mocha Celis High School. There, she met with veteran activists. "Some brilliant minds were there, and I wanted to learn, discursive tools, how to think collectively," she says.

Carnival and transvestite power

The Gualeguaychú Carnival is one of the most important popular festivals in the country. It is also one of the main economic activities, shaping the lives of a significant part of the community. “The carnival is the first job we trans women found in Gualeguaychú . And that means the city has always coexisted with sexual diversity,” she points out.

— What place does carnival hold in your story?

—We queer people are naturally very passionate about art. Imagine: it's pure magic: glitter, fabric, the chance to draw, decorate, create floats, make music, tell a story, bring it to life, materialize it. We enjoy that space. My last job there was in 2011, before I graduated, with the Kamarr Carnival Troupe . I covered the twelve-meter-long, seven-meter-high float with sculptures carved from polystyrene foam—a completely handcrafted job. Gualeguaychú has the best carvers because what's done here is pure talent. Nobody can teach you how to carve a seven-meter-tall demon: it's talent, and the surpassing of one's own work.

— Did you always dance at the carnival?

— Since 2005. I transitioned in Carnival, in the Comparsa O Bahía. I was also employed by Carnival. Before graduating as a teacher in 2011, I worked in Carnival—. But the transition doesn't happen all at once and forever in anyone's life.

Shared futures

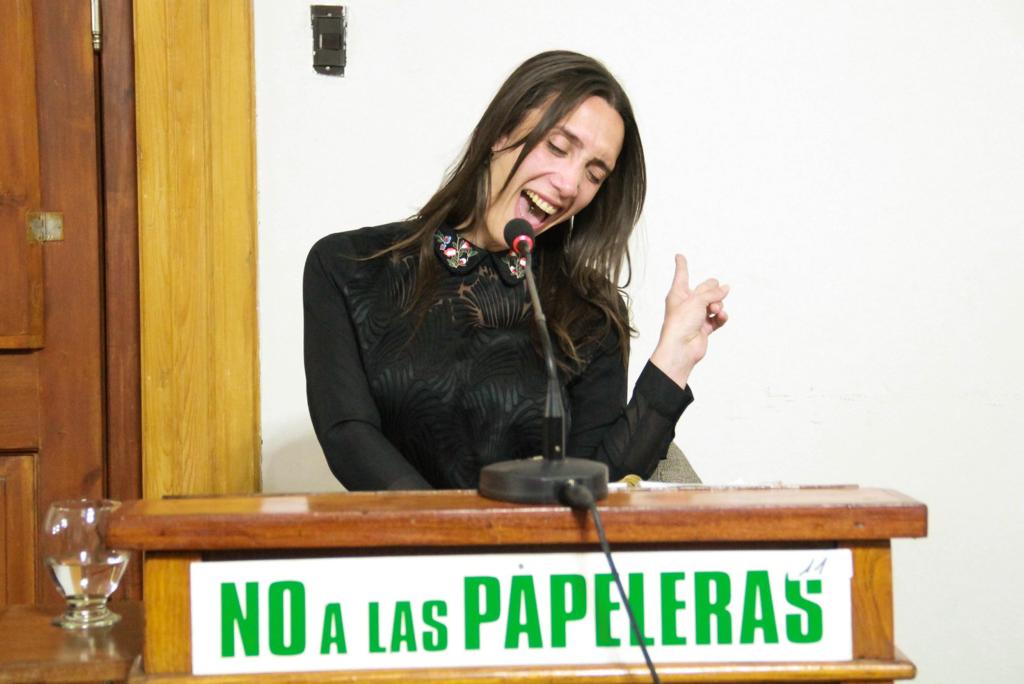

Besides being famous for its Carnival, the city of Gualeguaychú has a strong environmental activism movement. In 2006, the fight against the installation of two pulp mills (for making paper) on the Uruguayan side, in Fray Bentos, reached its peak. Large demonstrations disrupted traffic on the international bridge, sparking a conflict between the two countries. “The whole city organized to block the bridge with the Environmental Assembly. The blockade is still there to this day,” recalls the councilwoman.

Gualeguaychú is one of the first Argentine towns to have an ordinance against agrochemicals , and its current mayor, Esteban Martín Piaggio , set out from his first term (which began in 2015) to ban glyphosate, a poison associated with the production of transgenic soybeans.

Years before agreeing to join the city council list, Manu had a long conversation with Mayor Esteban Martín Piaggio. He had called her after her story became known in the city through a report in a local media outlet in mid-2016. “The transvestite teacher” thus began her activism, a public life dedicated to the rights of all, starting with her friends.

Although she considered the Justicialist Party to be sexist, as a citizen she positively evaluated Piaggio's administration, which was re-elected in 2019. She thought that building within this political space could be an opportunity to help the trans population. She envisioned projects that are now a reality, such as the trans employment quota and a "House of Diversity." This is a specific institution for addressing the issues faced by LGBT+ people and their families within the framework of Childhood, Adolescence, and Youth, which is about to open.

In the 2021 elections, she was offered a spot on the list, number 10. But nine council members were elected. She continued working as a teacher. Later, the local government appointed her to the Directorate of Diversity.

Pride to fight for more rights

— Did you ever imagine yourself as a municipal employee?

— The campaign went very well. The old guard of Peronism, those in the back, gauges your approval, and I received a wonderful welcome. It was December 2019, and I took a teaching position, but after a while, I was offered the directorship, along with María Belén Miré, from the local feminist movement, focusing on issues related to gender violence and care work; and I was working on reparations: for a sector that had never been considered, building from scratch, with the challenge of instilling a diversity perspective into municipal politics. Through the quota system, we've already brought in a colleague in Sports, another in Social Economy, a survivor in the Production and Economic Development Secretariat, and Gabriela, who works at the municipal reception desk. And we're about to inaugurate the House of Diversity.

—In this electoral scenario, what is your view on the future?

"This is a moment to call on the entire LGBT community to get involved. There are people who, from a position of privilege, celebrate the advance of the right wing. We have to organize. November 11th is the Pride march in Gualeguaychú, the third one. It doesn't have such a festive feel, and we're scared. It might not be to celebrate Pride, but to reclaim it, to fight for our rights and for democracy. For me, freedom means more rights, not fewer . Especially to defend the historic victories of this community. The new generations have already grown up with normative frameworks, and it's urgent to provide context. Lohana, Diana, Marlene (Wayar), Alba (Rueda), wonderful comrades, survivors like Carol, Dulce… they tell terrifying stories: when they were kids, they weren't even given mate, they had buckets of cold water thrown on them in winter. How many lives has the struggle claimed? This is a moment for collective reflection: What kind of society, city, and country do we want? We have to create murals that say ' Freedom means more rights.'"

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.