Without state support, mothers in El Salvador tell how they organize to search for their missing children

Faced with the lack of response from the authorities, a group of women organized themselves to search for clues and leads about their missing relatives in the context of gang-related social violence.

Share

SAN SALVADOR, El Salvador. “Every time I come back from a day of searching for my daughter, my two grandchildren ask me why I don’t bring their mother,” says Beatriz Hernández, a Salvadoran woman. My daughter, Marcela Jackelin Rodas Hernández, worked at a flower shop in one of the capital’s markets. She disappeared on April 19, 2021, on her way to work . She was possibly taken off the bus, but we don’t know for sure.

“She didn’t even make it to work. She didn’t come home either. We still don’t know anything about her,” the 42-year-old woman told Presentes.

"Since my daughter disappeared, I had to give up selling things at a school house to dedicate myself to the search and take care of my two grandchildren, as well as my two children. Explaining this whole situation to the children is very difficult. My grandchildren, ages 9 and 5, tell me: 'Maybe my mom doesn't love us anymore, she doesn't love us because she hasn't written to us.'"

The silence of the authorities

Beatriz explains how the organization of her household has also changed. “My husband, Nicolás Rodas, has had to take on all the household expenses. He works as an electrician, and during this time he has had health problems that have affected his work. All this worry has also caused me complications,” she says.

“Since I filed the report of my daughter’s disappearance, the authorities haven’t told me anything. What’s more, the case was about to be closed because I never even went to inquire. The detectives told me they were going to do everything, that I shouldn’t go anywhere, that I shouldn’t move, that they would handle it, and that they would keep me informed as the case progressed. But they never notified me of anything.”

Every eight days, Beatriz goes to the Forensic Institute of Legal Medicine to ask about her daughter. “I look for her every day,” she says.

Since February, the woman has been part of the Missing Persons Search Unit . “We attend training sessions, we learn how to develop our search skills, we have spaces to talk about what we are experiencing with a psychologist. Since we are living through a daily grieving process, we always talk about that.”

“We want (the authorities) to give us some good news. It’s been a long time, and we want to know about our children. We want them to search for them, to help us search for them, because it’s not fair that they’re leaving us to handle this. We’re not the authorities. We’re just mothers who go out and risk our lives with nothing but our bare hands. At least they’re armed; they have ways to defend themselves,” Hernández said.

Disappearances: a practice that has lasted for years in El Salvador

El Salvador has always had missing persons. Among the most recent cases are the victims of the civil war (1980-1992) between the Army and the former leftist guerrilla group, the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN), which left 75,000 dead and 8,000 missing.

In the post-war period, the problem persisted. Between 2014 and 2019, a five-year period that will go down in history as one of the most violent and deadly in the country, the Attorney General's Office reported more than 20,000 cases. The disappearances were mainly linked to gangs, known as maras, organized crime, and even personal feuds and revenge.

According to various human rights organizations, between 2019 and June 2022, the number of missing persons in the impoverished Central American country was around 6,443. Of that number, 2,397 cases were considered active.

“The main hypothesis is that the cases are due to gang violence. These young people were victims of organized crime, known as gangs, in different situations. They were targeted for recruitment and refused, their family businesses owed extortion money, or they crossed into rival territories. The gang divides territory, and in different circumstances, they became victims of organized crime,” Idalia Zepeda, a lawyer with the Salvadoran Association for Human Rights (ASDEHU) and part of the missing persons team, Presentes

According to experts, gangs typically follow a pattern: first, they kidnap their victims, torture them, murder them, and then bury them in clandestine graves or cemeteries. These sites are only investigated when authorities have a witness in a criminal case who testifies that people are buried there.

Emerging in the US city of Los Angeles in the nineties, hundreds of Salvadoran gang members were deported to their country of origin, where they settled and created groups that controlled the neighborhoods under threat of death to those who defied their rules.

In search of solidarity

“Stop putting up that garbage!” they yell at us when we hold poster campaigns with the photograph of my missing son Carlos Ernesto Santos Abarca’s face,” Eneida Abarca recalls bitterly.

“My son disappeared 20 months ago. He is a university student studying psychology, he studied English at the American School and has no criminal record. He had been in medical treatment for bipolar disorder for a year. At this point, it is assumed that his mind is blank.”

Carlos Ernesto went for a run on January 1, 2022, and never returned. “I never imagined he would disappear, much less for so long. Those who haven't had a loved one disappear, especially a child, should be more empathetic,” she told Presentes .

“There is intense online violence directed at me,” says Eneida Abarca. “They say I’ve politicized the case, that the media and political parties are funding me, and that’s not true. They also demand that we stop polluting the city, they revictimize us, saying that we are to blame because we didn’t take good care of my son.”

Without state support

Among all the actions Eneida has taken to find her son, she recounts traveling to 30 municipalities, organizing mass poster campaigns and searching for information or clues. “We’ve gone to the police, the courts, the forensic institute, hospitals, high-crime areas, the Presidential Palace. My sister Ivette, who is with me, has sores on her feet. During these searches, my documents and cell phone have been stolen… Once, a man chased me on a motorcycle and kept demanding I get on.”

She also points out that the tasks they, as family members, perform fall under the jurisdiction of the police. “The Urgent Action Protocol (PAU) for missing persons outlines the guidelines they must follow: body searches, rescue operations, and online searches.”

“I am doing all the work that corresponds to them, but there have been no results,” said Abarca, who alternates his work distributing hospital clothing with caring for his other two children and the search efforts.

“My husband, Ricardo Santos, who initiated the investigation, has shouldered the entire financial burden. Everything I earn and everything my sister makes from catalog sales goes toward the search. We spend $20 a day on printing posters. It's been 20 months and there's still no response from the government. A third team of prosecutors is now on the case; the first two were negligent. The third team didn't review the security camera footage, and they say they're rereading the file, but there are still no answers.”

“That’s why I joined the Bloc, because I can’t find any support from the authorities. All they tell you is that the investigations are ongoing and that it’s not just your case,” he said.

A space to accompany

In February 2022, a group of family members - mostly women - created the Search Bloc for Missing Persons as a result of the absence of a State that does not fulfill its role, neither in the prevention nor in the fight against this crime, say its creators.

They often travel on the "miracle bus" to post photos, talk to people, and visit institutions to demand answers. They also maintain a social media campaign, #ForThePeopleWeAreMissing, and organize a photo exhibit of their missing relatives, offering flowers in the main square of the capital, San Salvador.

Currently, the members are seeking to resolve some 35 cases of missing persons, reported between 2006 and 2022. The search group does not have its own budget, so human rights organizations support them with the basics, and they also manage their own resources as a family.

“In general, there has been neglect by the State in successive governments, not just this one. There is a common denominator: State institutions have not put the issue of disappearances on the agenda; there is no law on disappearances, no public policy to assist families of the disappeared, no emotional support,” stated lawyer and social activist Idalia Zepeda .

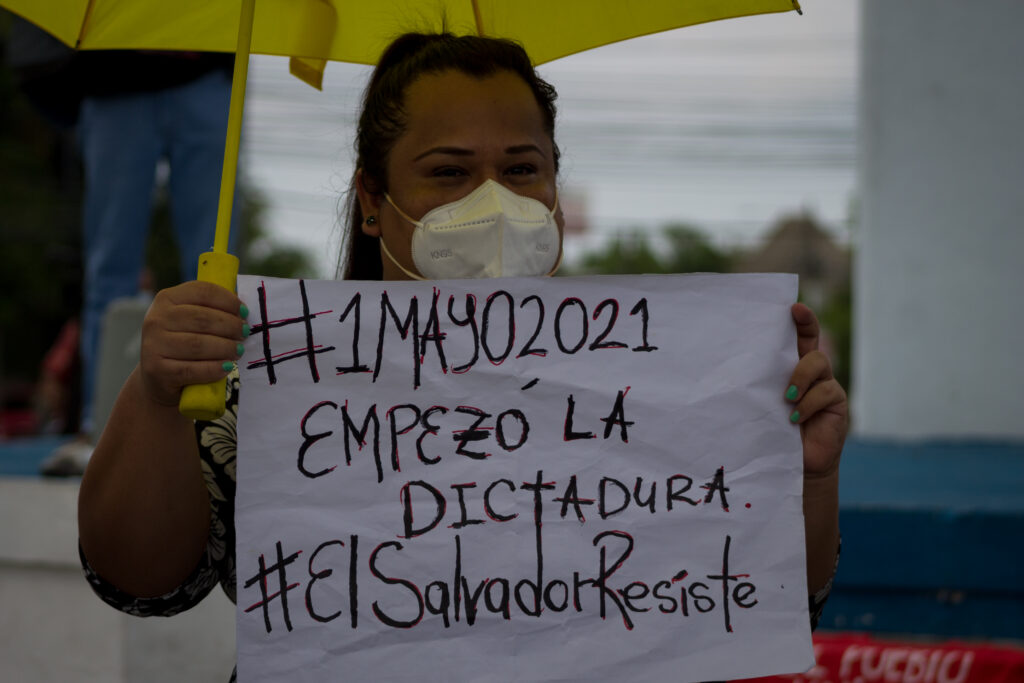

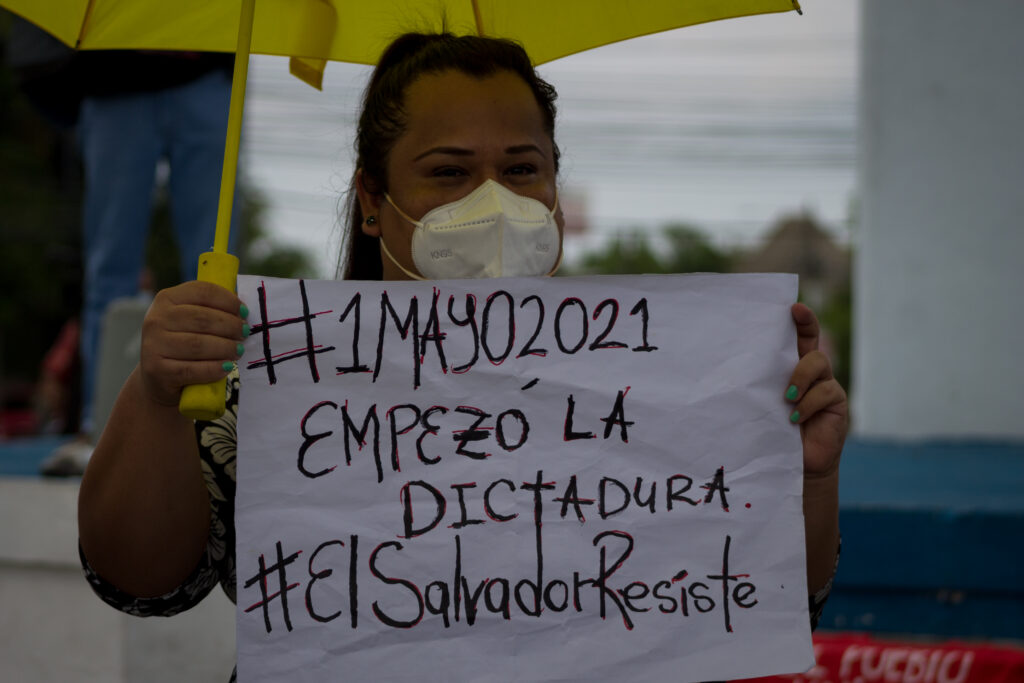

The members of the bloc requested that President Nayib Bukele's government allocate the necessary resources so that the institutions responsible for locating the detained individuals and investigating these crimes can exercise their powers and address the demands of the victims.

Furthermore, they request the establishment of an inter-institutional and binding committee to, in communication and coordination with family members and human rights organizations, create a registry of missing persons and a DNA database to facilitate the rapid location of missing persons.

Meanwhile, they demand that Congress—controlled by Bukele's ruling party—initiate a dialogue process with victims, human rights organizations, and experts that culminates in the approval of a law that includes elements for prevention, investigation, justice, comprehensive reparation, and guarantees of non-repetition.

“The State still has not managed to respond effectively, diligently, and seriously to the investigation,” Zepeda said.

The Prosecutor's Office and the police did not respond to a request for official comment from Agencia Presentes .

“No one ever lent me a hand to help me”

“My son, Juan Carlos Serrano Alvarado, disappeared on August 31, 2020. I filed a report with the police and the prosecutor's office, but no one ever helped me with his case,” says his mother, who asks to remain anonymous for security reasons . Juan Carlos worked as a delivery driver for a soft drink bottling company.

He used to study nursing, but during the COVID-19 pandemic he had to find a job to support his wife (who was unemployed) and his son, who was three months old at the time.

Juan Carlos disappeared in the municipality of Soyapango . The day he disappeared, he received a phone call and left, according to those who were the last to see him. He had just arrived at work. “With the loss of my son, we incurred expenses and took out loans, which, even now, is very difficult because we have no one to help us. We struggle day by day with our grief, trying to figure out how to move forward ,” he told Presentes .

“After we filed the report, the police stopped answering the phones. The officials won't face us; they're evasive. They say they can't enter neighborhoods to investigate because it's too dangerous. I think they even closed the case. They've told me they focus on solving cases involving children, but not with an older person, because they might be a gang member, they might be with someone, or they might be there of their own volition.”

“ So far, the only comfort we have is them, the Search Bloc , because they do support us, they help us a lot, they give us food. They have been like a guardian angel because they are people who go out of their way to help us as women,” she expressed.

An exceptional regime that harmed

For more than a year, the Central American country has remained under a state of emergency , which suspends some constitutional rights and has allowed state security forces to detain more than 70,000 suspected gang members. A total of 7,000 people have been released because no links to the so-called maras were found.

According to official statistics, the number of homicides decreased by 56.8% in 2022 compared to the previous year, due to the measure. However, it has also generated criticism from human rights organizations that denounce arbitrary arrests, human rights violations, and 174 deaths of people in state custody.

Despite advances in security, statistics on missing persons, investigations, and case resolutions have been classified as "confidential information." For this reason, victims' families have not been kept informed of the status of their cases.

“Right now, we don’t have accurate information, neither on the number of missing persons reports nor on the (clandestine) cemeteries. When we’ve inquired, the officials who assist us say that this information is confidential, that they can’t reveal if there have been any discoveries in any area or if any bodies have been found. The families don’t know, which we believe violates their right to know all the necessary public information that contributes to the investigation and the search for their loved ones,” said lawyer Zepeda.

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.