“The Madwomen of '73”: A documentary about the Chilean state’s persecution of LGBT+ people

Journalist Víctor Hugo Robles, “the Che of the gays”, interviews the protagonists of the first protest of sexual diversity that took place on April 22, 1973 in Santiago de Chile.

Share

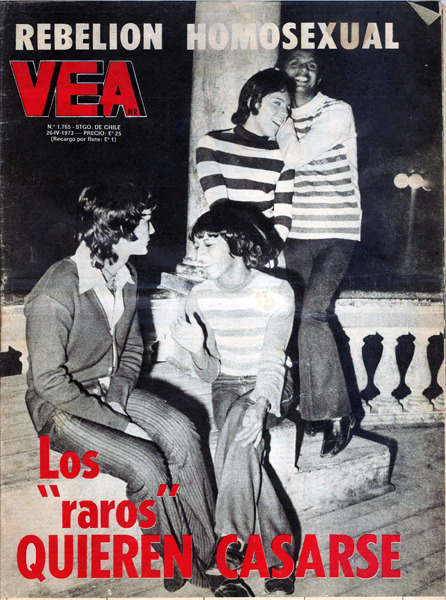

Fifty years after the Chilean military coup, a documentary tells the story of those who "threw the first stone" to demand LGBTQ+ rights in Chile. In *Las locas del 73* ( ), journalist Víctor Hugo Robles , "the Che Guevara of the gays," interviews the protagonists of the first LGBTQ+ protest, which took place on April 22, 1973, in Santiago, Chile.

“There’s a great desire to know what happened. Historical records are gaining more value; people want to listen, to know how they lived their lives, and to meet those who threw the first stone,” Robles told Presentes . Her feeling stems from the screenings so far of the film she produced and directed with journalist and anthropologist Carolina Espinoza .

The first of these events, exactly 50 years after the march, took place on April 22nd of this year at the Museum of Memory and Human Rights , where the 500 attendees overflowed the hall. The other events also took place in social and political spaces, such as the one held to benefit the Amaranta School , which serves transgender children, following a series of robberies the institution had suffered. The women featured in the film were especially moved when the documentary was presented at the National Stadium , a site of detention and torture during the Chilean military dictatorship led by Augusto Pinochet. In each of the presentations, the focus was on connection, intergenerational dialogue, and engagement with the entire community.

The Invisibles

“Only now are people talking about the LGBTQ+ victims of the dictatorship. They were always there, but they were invisible,” Robles shared. With the advent of democracy, there were various efforts in Chile to compile a registry of the dictatorship's victims. In addition to the Rettig Report Valech Commission published two reports in 2004 and 2010. These reports recognize a total of 40,018 victims of the dictatorship, 3,065 of whom were killed or disappeared. Recently, President Gabriel Boric announced that he will search for the 1,162 people who disappeared during this period through a National Search Plan .

To date, there is no official count of LGBTQ+ people persecuted or killed by the Armed Forces during this period. Only one crime has received official attention: the murder of a gay man discovered having relations with a soldier in 1975 at the ammunition depots on the Morro de Arica, for which he was ordered to be executed. The case came to light after Bernabé Vega, a retired sailor, confessed to the crime in 2010 at the age of 73 .

“Throughout this entire 50-year period, there has been no interest, no initiative on the part of the State to address this debt, this massacre, this violation of the human rights of sexual minorities,” Robles asserted. In this sense, “the documentary opens that door and becomes a living archive, a concrete precedent,” she said.

In all eras

During the film, La medallita, Marcela Dimonti, Brenda and Marco Ruiz give voice to the experiences they lived during the government of Salvador Allende (1970-1973), the subsequent military dictatorship (1973-1990) and share the current demands of sexual diversity.

– In the documentary, the protagonists recount that Allende's rise to power was seen at the time as an opportunity for expanded freedoms. However, the first LGBTQ+ march in Chilean history took place toward the end of his presidency. What was the situation for sexual diversity during the Popular Unity government?

What the women who participated in the protests point out in the discussions we hold during the documentary screenings is that this protest wasn't against Allende himself, but against police repression, which didn't only occur under Allende's government, but also under previous administrations. It was a manifestation of weariness, against repression, abuse, discrimination, and stigma. Of course, it also occurred under the Popular Unity government, which failed to incorporate this "new man"—as Che Guevara would say—but rather "the queer woman," the new transvestite. The contradiction is that it all happened amidst a whole process of popular progress, the acquisition of rights for the most vulnerable, the most persecuted, the stigmatized, those at the bottom. There is a debt and an open wound .

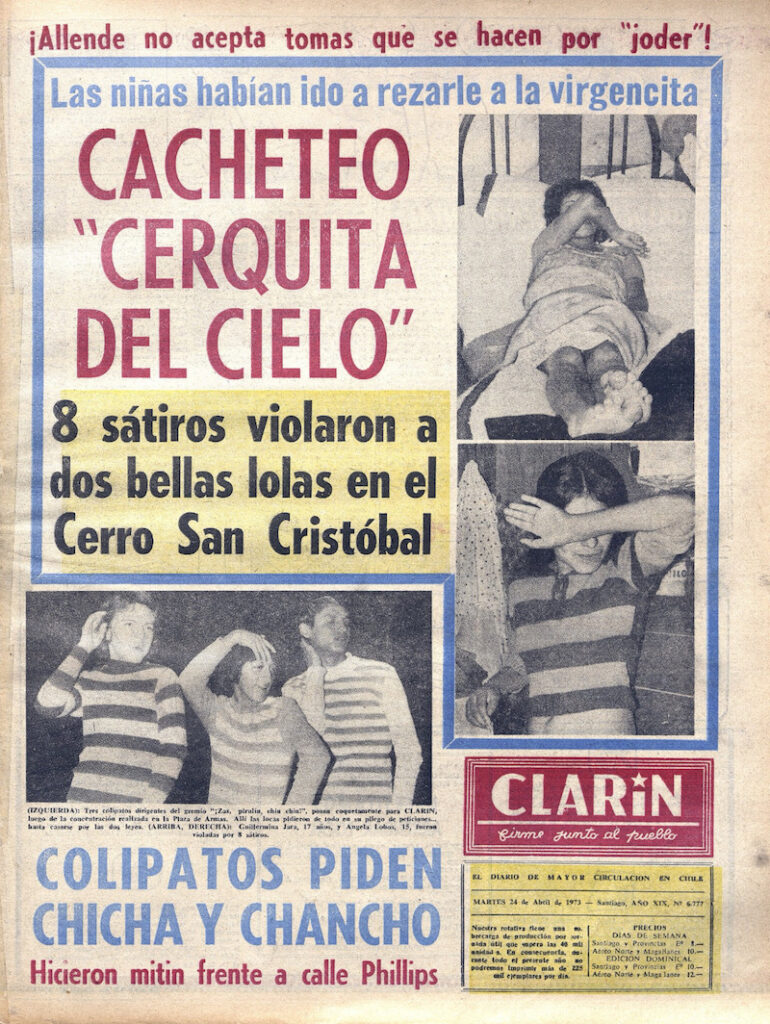

It's important to note that it was an authorized march. There was no repression during the march itself, which is quite surprising. There was repression afterward, though. When it appeared on the front page of every newspaper the following day, it was clearly a political order to persecute LGBTQ+ individuals. What hurts, disturbs, and upsets the most is that it was the mainstream and left-leaning press that wrote the most homophobic headlines in Chilean history.

Robles refers, for example, to the headline of the left-wing newspaper El Clarín , from April 24, 1973. Its front page featured a headline about the demonstration: “Colipatos demand chicha and pork. They held a rally in front of Phillips Street.” Furthermore, the article about the demonstration was subtitled “Repugnant spectacle, and the police?”

Triple punishment under dictatorship

Allende's government suffered a coup d'état led by the Armed Forces and Law Enforcement on September 11, 1973. The dictatorship under Pinochet lasted 17 years until 1990, after 56% voted against the dictator in a plebiscite held in October 1988.

– What were the particularities of the persecution of LGBTI people during the dictatorship?

– VHR: The Pinochet dictatorship was misogynistic, classist, and homophobic. When the military encountered a detainee who was openly gay or transgender, they faced double or triple punishment. All forms of dissent were persecuted under the dictatorship, particularly sexual dissent. People experienced not only homophobia but outright murder. The documentary itself includes recurring names: such-and-such a friend, such-and-such a person was massacred, they were found dead.

– With the advent of democracy, did this violence cease or continue?

– There was a radical change. It was a “negotiated” democracy, as we call it, because there was a pact between the coup-plotting military and other civilians. It was a slow process. But it can indeed be said that Chile has made progress in legislation, from the repeal of the sodomy law, to the Anti-Discrimination Law, the Marriage Equality Law, and the Gender Identity Law. But throughout this entire 50-year period, there has been no interest, no initiative on the part of the State, of its institutions, to address this debt, this massacre, this violation of the human rights of sexual minorities.

– What are the group's current demands?

– The older trans community wants a reparations law. Our trans women are demanding compensation, improvements in healthcare, education, housing, employment, and pensions because they believe the State owes them a debt. One of the government's first initiatives, through President Boric's partner and Irina Caramano, was to create a sexual diversity and transgender task force where all these initiatives were brought together. It is highly unlikely that Parliament will be open to passing a reparations law at this time.

– In Chile, as in Argentina, there is also an advance of radicalized right-wing groups.

Unfortunately, in recent times there has been an advance of the right wing, and particularly of evangelical groups, which puts these hard-won rights at risk. What you are experiencing with Milei, we are also experiencing with a hardline, extreme, fascist right wing that has popular support. This is compounded by the fact that hate crimes have not stopped, and by an institutional framework that is not being strengthened. For example, the Anti-Discrimination Law is somewhat flawed because it doesn't prevent discrimination, but rather punishes the discriminator. To address this, we need to create educational institutions. That is the challenge now.

For Robles, it's about "making the impossible possible." In this sense, she called not only for paying tribute to the trans survivors of the dictatorship, but also for being part of the path toward their reparation. "Because, as La Medallita rightly says, they don't live on applause," she stated.

“It would be very interesting if the LGBTQ+ community in Argentina invited us to present the documentary in Buenos Aires or other cities in Argentina. We also want to call on the Chilean Ambassador to Argentina, Bárbara Figueroa, and the Embassy's Cultural Attaché, Alejandro Goic, to open doors for us and give us the support we need to travel with our colleagues to present this documentary and engage in dialogue with the LGBTQ+ community in Argentina about these shared demands,” she concluded.

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.