“Today El Salvador is a joyless society,” says psychologist who evaluates victims of the state of emergency.

Psychologist Paulita Pike discusses the consequences for innocent victims within the framework of the state of emergency imposed by the government of El Salvador.

Share

SAN SALVADOR, El Salvador. In the late 1970s, a large group of women, carrying papers, frequented a small shop next to the Jesuit school where Paulita Pike, . The constant flow of people caught her attention. One day she decided to approach them to ask why they were there: “These are photos of our disappeared loved ones, and we’ve come to report it,” she recalls them telling her.

The people presented their cases to the Legal Aid office, an organization founded by Father Segundo Montes (1933-1989) and later led by the now Saint Óscar Arnulfo Romero (1917-1980). Both religious figures were assassinated in different years for denouncing injustices and demanding the defense of human rights during a time of social upheaval and civil war (1980-1992).

Pike joined the office team until May 1980, when a group of soldiers raided her home looking for weapons or guerrilla propaganda. Although they found nothing, she was detained in the police station's dungeons for ten days. After her release, she was forced into exile in various countries, where she continues her work defending human rights.

The violence that never ends

Four decades later, the premises of the Humanitarian Legal Aid Center have once again been filled with relatives who are denouncing arbitrary arrests, abuses, harassment and torture within the framework of a state of emergency that seeks to combat the dangerous gangs operating in the Central American country.

On the last weekend of March 2022, a total of 87 people were murdered. The killings were attributed to gangs, so the controversial Salvadoran president, Nayib Bukele, asked Congress to declare a state of emergency that suspends some constitutional guarantees .

The measure is popular among Salvadorans because it reduced the number of homicides by 81.3% between January and July, compared to the same period the previous year. The state of emergency remains in effect and has been extended for 17 months.

Since then, soldiers and police have arrested more than 72,000 suspected gang members, some cities and towns are surrounded by state security groups, thousands of people are being held in overcrowded jails awaiting trial, while their relatives seek information about their well-being from various institutions.

Human rights organizations have reported that thousands of innocent people are detained simply because of where they live, based on suspicion, anonymous tips, or to meet daily arrest quotas. Official figures estimate that more than 6,000 people have been released and more than 170 have died in state custody, without any investigations by the authorities.

In an interview with Agencia Presentes , Paulita Pike maintains that those detained are not the only victims of the state of emergency. Their families are also victims. The Psychological Support Secretariat of the Humanitarian Legal Aid organization has identified more than 75,000 children and adolescents abandoned by the state. They have also provided care to dozens of released individuals, who have been identified as exhibiting detachment from reality, low self-esteem, severe depression and anxiety, and a tendency to cry and feel distressed.

– –El Salvador has gone from the trauma of civil war in the 1980s, then to three decades of social and gang violence, and now to the coercion of the state of emergency. It sounds like a spiral that seems to have no end.

– That's so true, and yet so complicated. We can go back much further. In 1932, with Feliciano Ama, whose family in Izalco is still afraid. They don't want to talk about what happened 100 years ago. The fear is still there, latent in their bodies. But let's go back 100 years earlier, to the indigenous man (Anastasio) Aquino, in 1832. I mean, what happens in this country every hundred years? We're already approaching the centennial of 1932, and in the middle of it all, we had a civil war that left between 80,000 and 100,000 dead. Such a small state, only 21,000 square kilometers, that we can't even respect each other when we disagree. There's never a moment of peace in this country.

The specialist is referring to the 1932 massacre of Indigenous people in the western part of the country, following an armed uprising against the government of dictator Maximiliano Hernández Martínez. Fearing reprisals, many communities abandoned their language, clothing, and traditions. One hundred years earlier, there had been an uprising led by Anastasio Aquino in the central part of the country.

– What is your interpretation of the current situation?

– The lack of the rule of law. Democracy is the best; it's not perfect, but it's the best of all forms of government. In a democracy, at least we know what to expect . We know that if we break the law, we'll be punished for breaking it. Not like now, where it's the law of the jungle. And just because you're poor and live in a marginalized community, and the police have to meet their arrest quotas, they take all these poor kids, who we know are innocent. If they were criminals or terrorists, as they love to say, they wouldn't be getting out.

The consequences of the state of emergency

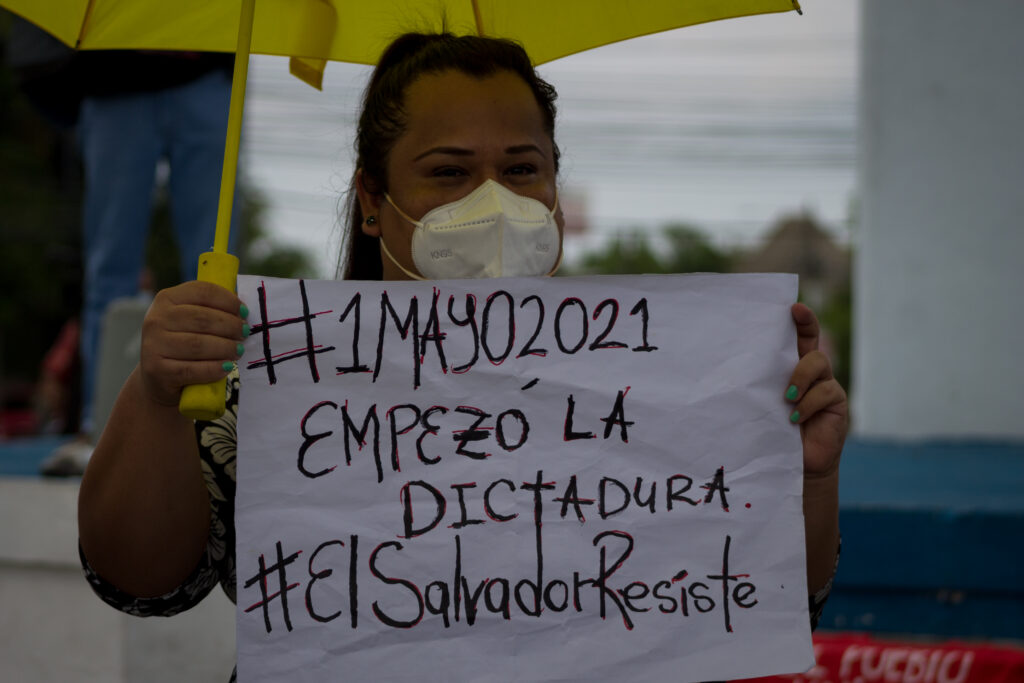

Since Bukele came to power in June 2019 and secured a supermajority in Congress in 2021, the ruling party has dismantled the Supreme Court and the Attorney General's Office to install its allies. It has also dismissed judges and suspended an agreement with the Organization of American States (OAS) to establish a commission against corruption.

In fact, the Supreme Court justices issued a ruling in September 2021 to allow re-election, even though it is prohibited by the Constitution.

– How has the mental health of Salvadorans deteriorated after a year of the state of emergency in the country?

– We cannot speak of this state of exception in a vacuum, because it doesn't exist in a vacuum. Gangs emerged as a consequence of the civil war. They didn't exist until the civil war began, and they have persisted thanks to all the governments that failed to address the problem properly, didn't know how to address it, or didn't want to address it .

So, these kids who were abandoned during the war, either because their families were killed in the massacres or because they went north in search of a better life, left their children here. Later, these children went to Los Angeles, in the United States. They grow up in Los Angeles, which isn't their country, and develop their own dialect, a sense of belonging. Because they don't have families, and when they're deported, well, what else would happen? They stick together. And as I imagine, their goal is to grow, like a family, like another business.

This generation is emerging traumatized by the violence that began in the 80s. It's not a cliché. At first, I said, "People who say 'if you don't know history, you'll repeat it'—that's a rather cheap cliché," but I'm seeing it for real. We are indeed repeating it, and we will continue to repeat it. It's a violent, ignorant, arrogant society. It's the least compassionate people.

– There are psychological effects due to the uncertainty surrounding the location and condition of their detained relatives. You have said that people “have a right to know.” Why?

– The cruelest thing for me is that the family isn't told where the detainee is. Or whether they're alive or dead.

– How does this whole situation affect wives, mothers, and life partners?

“I can’t talk about percentages. I don’t know what percentage of the detainees’ households are supported by both parents or how many are supported only by the man. Many of these households are dysfunctional. So, if the mother is taken away, those children are left completely abandoned, because the grandmother is already old or no longer there. Those children won’t eat well, they won’t go to school, they won’t have love, they won’t have any support; they’ll grow up in the wilderness. The women who remain as the breadwinners are another matter entirely. They’ve never worked. Many of them are very humble people, extremely poor, whose highest education has perhaps been up to the fifth grade. So, the husbands were the ones who went out to earn a living; they never did.”

– It has been mentioned that some 75,000 children and adolescents are abandoned, without receiving support from the State. Legal Aid provides emotional support for children. What are the circumstances and characteristics they present?

–If they take the father away first, if the children see it, that alone traumatizes them, seeing how they're treated when they're taken away. Being beaten, being called "sons of bitches" and other names, being thrown into the patrol car, being handcuffed. Immediately, the children are left with nightmares, they burst into tears at any moment.

I think that's another description; it's a depressed society, not a joyful one. We think we are like that. It's a society without much joy, and the children, I think, are the best reflection of it. They're emaciated, they don't have proper nutrition. They have nightmares. It's terrible to live with those nightmares. They dream they see their father or grandfather or brother who's been taken away. They dream they see him in jail, and sometimes they've drawn pictures of the jail bars and a figure. And inside, all you see is red. It's the blood that's coming out of the detainee. So, what trust can these children have in anyone? If their immediate family dies, who's left?

Getting out of jail, returning from war

– What are the main traumas or aftereffects experienced by people who leave prison?

– There's one guy who was there for 12 months, living in such extreme poverty. His mother never once brought him a package; only his sister came once. And I ask him, "How does that make you feel?" He gets all nervous and says, "Oh, well, yes, but you know, with poverty and not having any money..." Once he calls me and says, "I want to tell you that I have a terrible pain in my chest, right in the middle of my chest." It could be his ribs because they all get beaten with clubs during the initiation. We send them for ultrasounds, and it's not that; he has gastritis. But who doesn't come out of there with gastritis?

The other thing is that they come out covered in rashes from their shaved heads to their toenails, and they get fungal infections. They're covered in rashes all over their bodies. They come out depressed. But the thing is, they can't define or describe it because they don't even have the vocabulary to describe what they're feeling. It's really hard to give them hope.

– You've spoken in other forums about how men who are released from prison often have troubled relationships, and even their sex lives can become dysfunctional. They suffer from post-traumatic stress. They're not free. Could you elaborate on that?

– It's quite common that, when a man wants to have sex with his partner, he's unable to perform. That is, he's not motivated, he doesn't feel the desire, his libido is practically nonexistent. And the women don't know what to think because, in these macho countries, it's perfectly normal for them to have sex whenever the man wants, and they have a bunch of kids. It's never been seen that a man can't perform. That's an obvious symptom of deficiencies, of trauma, of fear, of everything he's suffered in prison.

Another characteristic is that they suffer from post-traumatic stress, similar to someone returning from war. In other words, many circumstances affect them, and these are of such magnitude that they accompany them for the rest of their lives. We are systematically observing these older and younger men who are released and who are easily frightened: a slamming door, a shout, dogs fighting in the street that may bring back memories of prison.

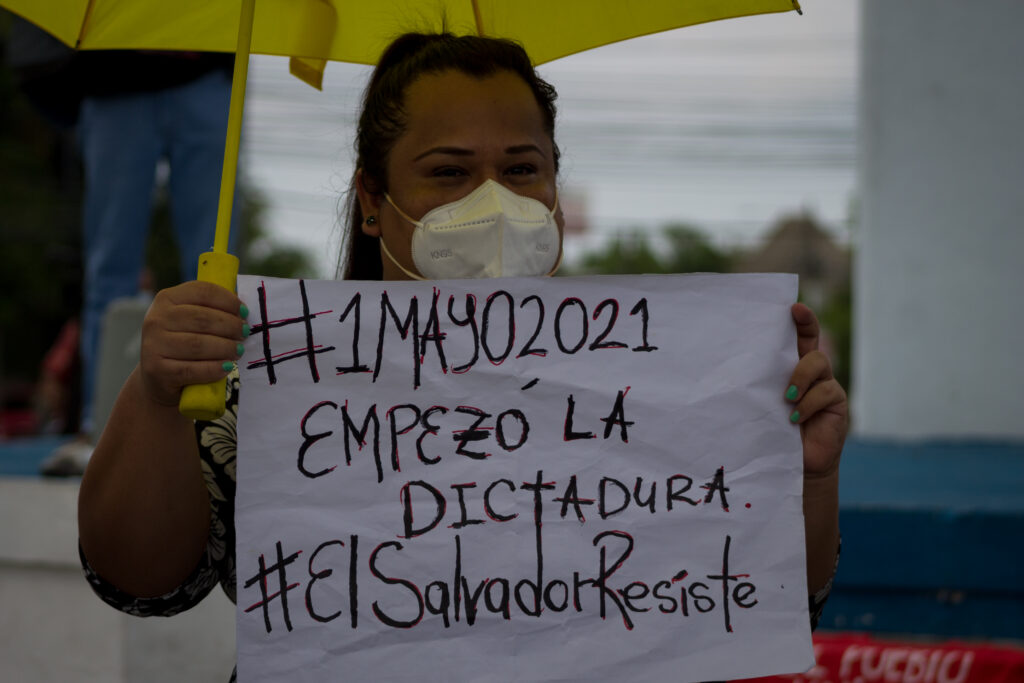

Photo: Paula Rosales.

– What are those sessions with the victims like?

" It's a given that everyone I've seen refuses to look at me . I tell them their name and tell them to look up. They look at me once. I tell them, 'Look at me again, but hold my gaze. Now let's lift our chins. Raise your faces, straighten your necks. Keep your necks straight and look at me.' They do it for a minute, two minutes, but immediately they lower their gaze again. It's the same posture they maintained in prison. And it's the same posture of total submission, a body language of surrender, of subjugation, zero self-esteem. Why do they want to look at me if I'm a cockroach, I'm worthless? And if I look at you, they might come with a club and beat me, or you won't get dinner today, or some other punishment. So, their body language is tense, submissive."

Depression. There's a deep depression there. They don't make any plans. They just live day to day. Let's see what happens. Maybe they'll come back today, maybe they won't. There's no future.

Salvadoran children

Paulita Pike recounts that one Christmas they arrived in a town with a few changes of clothes for each child. There were about 50 of them. Before handing them out, they told the children they had to bathe in order to wear the clean clothes.

“Everyone said, ‘Where are we going to bathe?’ That’s when I realized there’s no running water there. Where do they get their water? In a ravine. So, they put one of those big barrels out and we had a bathing party. At first, they were saying, ‘I don’t want to get wet, let the water be cold,’ but then they were shouting with joy. And since we had brought shampoo, that was the biggest novelty: ‘This has bubbles. This soap has bubbles, it has foam.’ They had never bathed with shampoo before. So everyone was happy. After that, nobody wanted to leave; everyone wanted to spend the whole day there, bathing in the water we were throwing on them. Then I thought to myself: it’s such a small joy, and I wish more people would get involved in these kinds of activities.”

– How will this whole situation affect the future?

– In the future, no one knows how this pattern of violent and selective behavior will develop psychologically, sociologically, and historically. Will there be consequences? Of course, as there are consequences after every traumatic event for a nation. Everyone experiences it in different ways. Our civil war ended relatively recently, in '92; we're barely recovering from the traumas of 12 years of war, and now the poorest segment of the population is exposed to this new trauma. Broadly speaking, there are consequences for the entire population as well, because there is also uncertainty. So, since we haven't emerged from this, but are only just beginning, we can only imagine what the future will be like for El Salvador: a traumatized population, a fearful population, a distrustful population. We will exhibit all the characteristics that a dictatorial regime imposes on us.

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.