Indigenous women at the forefront of the Third Peace March

After eight days of indifference from the Supreme Court and the government, the Third Peace March marched to the National Congress to carry out a whipalazo and demand the intervention of the province of Jujuy.

Share

“In Indigenous communities, it’s like that; women are almost always at the forefront,” says Susana, as she hands out flyers for the Third Peace March to passersby in front of the courthouse. And yes, there are a huge number of women of all ages among those peacefully occupying the plaza. They’ve been there for over a week , since they arrived in Buenos Aires on August 1st, Pachamama Day.

They carry the demands of more than 420 Indigenous communities in Jujuy. Unlike other demonstrations, this time the Buenos Aires City Government did not allow them to set up tents or awnings for shelter, but they remain, exposed to the elements, enduring the low temperatures with donated blankets and mattresses, devising daily strategies and activities to break through the media blackout and the indifference of the Supreme Court. Singing: “Five centuries of resistance, five centuries of courage.”

Wiphalazo at Congress

Today, on the International Day of the World's Indigenous Peoples, they called for a Wiphala protest. For a while, they left Lavalle Square and marched through the streets to the National Congress, where the Wiphala protest took place. They declared : “We, the Indigenous peoples, stand with the people of our province. We have been away from our territory for more than two weeks to let you know that in Jujuy we are witnessing a modern dictatorship under Governor Gerardo Morales .”

“We are not asking for money. We have come to ask that the reform be withdrawn and that the province of Jujuy be intervened,” said one of the indigenous sisters.

“Our women leave their children, their animals, and the territory that involves the relationship with Mother Earth in this month of August, Pachamama, an important time to be in the territory. Coming here is a form of uprooting ,” said Miriam Liempe, secretary of indigenous peoples of the CTA Autónoma.

Aurora

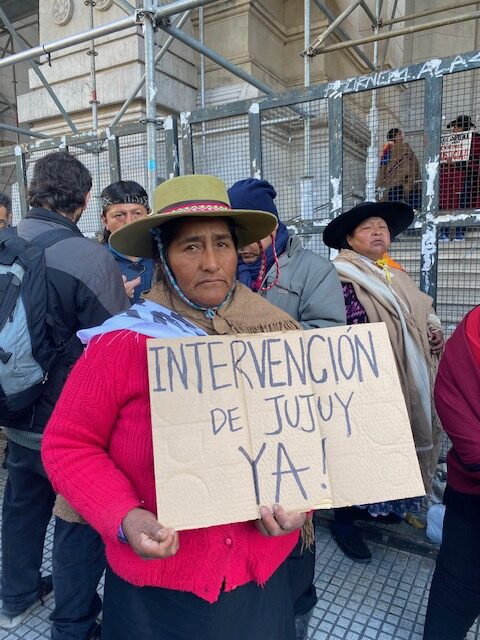

At the entrance to the Palace of Justice and around the plaza, police and security personnel patrol back and forth. And there stands Aurora Choque, her feet bandaged and covered with several pairs of socks, wearing the worn sandals she's worn in every city that welcomed the Malón since it left La Quiaca on July 25th.

Aurora lives in Coranzuli—she's from the Inti Yaku Apu Coyamboyq community—and wears the hat that protects her from the sun in that small town in the Puna region. Standing on the fence that blocks access to the courthouse, she holds her banner made of cardboard and a piece of fiber: "Intervention in Jujuy Now!" Her fuchsia sweater shines against the gray of the building and the fence.

“I’m here in court to request the province’s intervention. I’m against Morales’s reform that wants to take away our land and our water, and even our right to protest. We won’t leave without an answer,” says Aurora.

Miracles

When a silence falls, Milagros, one of the youngest participants in the Malón, grips the megaphone tightly and shouts: “Down with the reform, up with rights!” At 19, she came from her community in Pozo Colorado, in the department of Tumbaya, Salinas Grandes. Milagros was also there when the Malón began.

“I’m here to demand the repeal of the reform that we all know is unconstitutional, to demand that land titles be granted to Indigenous communities, and for Mother Earth. Near the salt flats, we have the lithium they want to exploit. The communities that live around here know that it could have serious consequences, not only affecting human health but also animals, and leaving other consequences beyond pollution, such as drought.”

"In our community we have been repressed several times"

“Stop the violence against Indigenous women for defending our rights,” reads the green cardboard sign hanging from Rosa’s neck. She is also at the courthouse entrance, where a wiphala banner has been hung that reads “Nullity of the reform,” signed by the sign painters of the Greater Buenos Aires area.

“I’m here for the repeal of the illegal reform. Because it was approved behind the people’s backs, at 5 in the morning, very quickly, without the free, prior, and informed consultation that was required. As pre-existing peoples, ILO Convention 169 speaks of our right to that consultation. The communities were not given any participation either,” Rosa explains.

She arrived in Buenos Aires from Palpalá. “In our community, we have been repressed several times. This is the third time we have suffered repression in recent years. The first time was in Palpalá in October 2020, for defending our territories. We experienced it a few weeks ago in Purmamarca. We are women, elderly women, there are children; we never imagined they would repress us in such a violent way. It was a hunt. The police were aiming for our heads, trying to hurt us,” she says.

Toughen the fight

Yesterday, three protesters chained their hands to the entrance of the courthouse and remain there on a hunger strike. “Our grandparents taught us to intensify our struggle when we are not heard,” says Susana, handing out flyers to those who come to the courthouse to support the protest.

Susana is from Pueblo Viejo, in Humahuaca. The flyers she distributes explain the demands of the Malón, offer a QR code, the Malón's Facebook page, and a detailed explanation of everything violated by Gerardo Morales' constitutional reform. "The Constitution approved in an expedited manner is a racist and genocidal tool against the people of Jujuy," the flyer states, "for the land, water, and life."

Some people greet it with a smile, others reject it. Susana remembers that during the protests, some women would get angry and yell at them: “Why are you cutting things down! You’re all just a bunch of Black women!” Susana laughs: “Someday, when they try to take something away from her, she’ll say, ‘Why didn’t I listen to those Black women?’”

“We came because back in Jujuy we’re censored, we’re not heard, we don’t get media coverage. And we don’t have justice. When we get back, we’ll face fines. I’m a little embarrassed to be in the photos, I’m not used to it. But we’re here to show and tell what’s happening in Jujuy. The grandmothers and grandfathers tell us what we have to fight for, like they did in the first protest march, and they give us strength.”

When the Malón stopped in Córdoba a few days ago, Susana was impressed by “the number of people and how they welcomed us. We all cried. That energy from those who approach us strengthens us to keep fighting.”

Nobel Peace Prize laureate Pérez Esquivel showed his support

As the hours pass, the air grows tense. Police are on the lookout. The elections are approaching. Those participating in the Malón are on high alert. Although the mainstream media doesn't cover them, their peaceful occupation continues. Various independent media outlets and reporters arrive daily. The Indigenous communicators from TeleSisaOficial and SisasMedio , using them to report on the agenda and the prevailing atmosphere.

Every evening, from 6 to 8 pm, a festival takes place in front of the courthouse. Many musical groups have performed, including Bruno Arias, Arbolito, murgas (street theater groups), and other artists. Throughout the day, donations are collected, and many people come to show their support and chat.

Yesterday, shortly after the three protesters chained themselves together, Nobel Peace Prize laureate Adolfo Pérez Esquivel, from the Peace and Justice Service (SERPAJ) , arrived accompanied by lawyer Mariana Katz . He managed to get past the courthouse barriers and meet with secretaries of the Supreme Court. Upon leaving, he and Katz told the few media outlets present: “The secretaries informed us that a new constitutional challenge to the reform has been filed, and the legal case initiated by the national government, which recently returned from the Attorney General's Office, is also underway.” Esquivel and Katz urged the Court to hear the representatives of the protesters.

“We have insisted that they be received. At this moment, some brothers have chained themselves up and will remain there until the Court receives them. It is a right you have; it is not a crime.”

Esquivel and Katz pointed out that it is at least strange that tents are not allowed to be set up when the City Government does allow them in Plaza de Mayo, for example, during a Qom protest. They also requested permission to install portable toilets.

Pérez Esquivel recalled that he had submitted a letter to the Supreme Court, even before the Malón arrived, requesting that the Court hear the voices of the Indigenous peoples who were coming to Buenos Aires, a letter that has yet to receive a response. “We will continue working until this Court receives them. This is racism, discrimination, and intolerance, not only on the part of the Court but also the City Government. This isn't just a case file; these are the faces of men and women who are demanding their rights, and those rights must be respected.” His remarks were followed with rapt attention, garnering applause, raised Wiphalas, and another chant.

Five centuries of resistance, five centuries of courage/Always maintaining the essence

It is your essence and it is a seed/and it is within us forever

Life is made with the Sun and it flourishes in Pachamama.

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.