Jujuy: The route of indigenous resistance from Perico to La Quiaca

A journalist from Presentes traveled along the roads and roadblocks in Jujuy, where Indigenous communities are leading protests, garnering support, and demanding the annulment of the reform to the Jujuy Constitution. They have begun a hunger strike and revived the tradition of mock crucifixion.

Share

LA QUIACA, special correspondent in Jujuy. Rosalinda Ancasi, “ the first trans woman to legally change her gender identity here in La Quiaca ,” takes turns with three other comrades participating in the road blockade in La Quiaca. Rosalinda is a municipal employee and a member of the Union of Municipal Employees and Workers (SEOM). She is here, she said, sitting on the bed where they spend their nights, “to help the communities,” even though she was born and raised in the urban area of La Quiaca. “We don’t like that the government passed the reform,” she told Presentes, standing at one of the eight blockades that have been maintained from the flatlands of Perico to La Quiaca , the last Argentine city before the border with the Plurinational State of Bolivia.

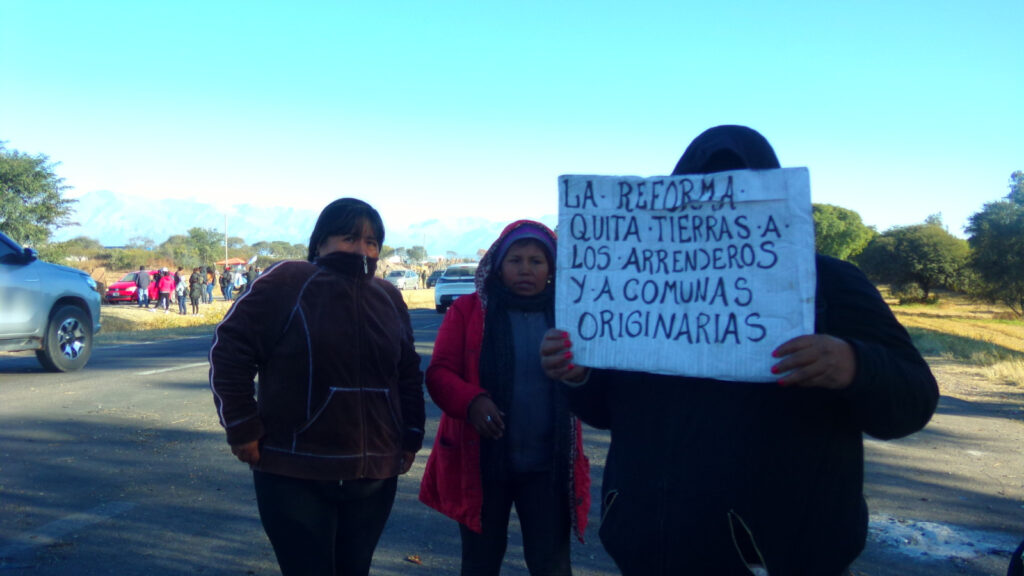

The Indigenous communities inhabiting the province of Jujuy continue their road blockades in protest against the reform of the provincial constitution. They consider it detrimental to their rights because, among other concerns, it leaves open the possibility of encroachment on Indigenous territory and criminalizes social protests . At every blockade, the same demand is repeated: the resignation of Governor Gerardo Morales (now the vice-presidential candidate for Juntos por el Cambio) and the annulment of the Jujuy constitutional reform. Unlike what happened on June 17, when the Jujuy police repressed the protest in Purmamarca by invading national highways, which fall under the jurisdiction of the national security forces, uniformed police officers are not seen at the blockades now. A few unarmed gendarmes are directing traffic when passage is permitted.

Support for protesters on the roads

Throughout the province of Jujuy, there seems to be widespread agreement on the legitimacy of the protest led by the indigenous communities . At the roadblocks, the protesters are treated with respect, and most drivers, regular commuters, and tourists express their support for the demonstrators , who also receive support through donations of food and warm clothing to make the cold winter nights in the Quebrada and the Puna more bearable, where temperatures drop below freezing.

Each protest adds its own particularities to the overall protest against the reform. In Perico , the demand, supported by a partial blockade of National Route 66 near the El Pongo farm , concerns the revenue generated by the medicinal cannabis plantation . As protesters pointed out, the farm was originally donated to the Jujuy provincial government so that the revenue generated would be used for the Perico hospital and "the poor of Perico." But that's not happening.

After the provincial capital, San Salvador, in the Quebrada de Humahuaca , the series of road blockades begins in Purmamarca . It's actually a blockade in the style of those carried out in Bolivia, a succession of obstacles: old railway tracks, large rocks, and tree trunks. From the roundabout where Routes 9 and 52 meet, they extend for about a hundred meters along both roads. It's a strategic point because Route 52 passes by Purmamarca and continues to the Jama Pass, where it enters Chilean territory.

The lithium route

This is the lithium route, leading to Salinas Grandes and Laguna de Guayatayoc, and then to Susques, where the Salar de Olaroz is located, home to the transnational mining operations Exxar and Sales de Jujuy. Meanwhile, Route 9 continues towards La Quiaca, ending at the international bridge that connects to the Bolivian city of Villazón.

Along Route 9, after the roadblock in Purmamarca, there's another one in Tilcara . The midday sun beats down on drivers who have to wait in the long line of vehicles until the new time when passage will be allowed, every six hours starting Saturday the 24th. And yet, when they can finally get through, the vast majority honk their horns in support of the protesters.

Further up the road, in the small town of Uquía (famous for its parish church with antique paintings of arquebusier angels), another protest is blocking traffic. A spokesperson who identified himself as Jorge explained that in this small village, 52 families live in a settlement. He accused the municipal commissioner, Gabriela Flores (from the ruling party in Jujuy), of being responsible. According to him, the 52 families used to live in the Quebrada de las Señoritas, a trail that climbs through a small canyon and is one of the tourist attractions of the Quebrada de Humahuaca. But the commissioner “took over the place” and doesn't allow them to live there. And, as in almost all of Jujuy, the slogan repeated at the Uquía roadblock is: “Morales has to go,” demanding that he cancel the reform. They are “fed up with the corruption” of the commissioners and with “Morales controlling them,” the spokesperson said.

Continuing along the route, a little beyond the Huasadurazno area in San Roque, shortly before the city of Humahuaca, another group blocks Route 9. After Humahuaca, there's another blockade near the Negra Muerta Community. There too, as at the other blockades Presentes visited, they fear the presence of infiltrators. They'll have to explain, show documents and credentials, mention mutual acquaintances, and ask for verification with them if necessary, to ease the distrust. Then Severiano, a community member (he won't give any more details), in his sixties, thin, of medium height, wearing dark clothes and a black hat, will share his knowledge of the territory he inhabits. He'll also voice his complaints about Gerardo Morales's administration.

Why land is not the same as territory

In that area, several communities have communal land titles , he said, but “through tremendous deception,” because those documents use the term “land” and not “territory.” This contradicts ILO Convention 169, which specifies that Indigenous peoples have the right to obtain title to the territories they have ancestrally inhabited . The difference is not merely semantic. Owning land only implies having rights to what is above it. Territory encompasses everything, including the spiritual realm, but also what lies beneath the surface, such as the minerals so precious today.

“The constitutional reform was designed to leave us without territory,” Severiano asserted. “And they won’t even leave us the land,” he added, as other community members nodded in agreement. “That’s why we’re here, to defend the territory for our children,” added some women who were listening, none of whom wanted to be identified. This is the experience they witness, the spokesperson continued, in El Pongo, in the town of Caspalá—where the Jujuy government destroyed community land and proceeded with construction projects without consultation or community consent—in Angosto de Perchel—where the Telecom company installed antennas and fiber optic cables without consultation or consent—and in Salinas Grandes with the lithium mining.

“Let’s talk about lithium ,” Severiano suggested. “Soon we won’t have any water; we’re already experiencing drought,” he added. The environmental damage is evident in that area of the Quebrada, he insisted, gesturing westward with his left arm. There, behind the hills, lies Minera Aguilar, established in 1930, which mines zinc, lead, silver, and cadmium, and whose directors were complicit in state terrorism . “Until 1970, those hills were covered in snow year-round,” the spokesperson recalled. And to top it all off, further up in Abra Pampa, along Route 9, they intend to build a landfill as part of the GIRSU Plan promoted by the provincial government. That will contaminate the water downstream, Severiano asserted.

Peaceful raids yesterday and today

Other inhabitants of that area, which extends into the Puna plateau, would echo similar reasons for rejecting the province's new constitution. At the Condorcito cemetery, where he went to attend the burial of his uncle Felipe Mamaní , Luciano Mamaní would lament the reform. He would also emphasize the value of the protest being carried out by the community members, which they called the Third Malón de la Paz (Peace Raid). Indeed, Felipe Mamaní, at the age of 18, was one of the participants in the First Malón de la Paz , held in 1946. He, too, was demanding recognition of their territorial rights.

At the same cemetery, another relative, now a teacher in Abra Pampa and a participant in the protest in that Puna city, bid him farewell. There, the community organization maintains a blockade of Route 9 for about a hundred meters. They improvise shelters with wooden platforms and light fires in the center to ward off the night's cold. A group of community members chants, "Down with the reform." Here too, the protesters prefer not to identify themselves.

La Quiaca: Hunger strike and crucifixion

The last place where the reform is being resisted is the access road to La Quiaca. A blockade stretches for about a hundred meters, with shelters on both sides of the road. There, leaders of indigenous communities from the Puna region, social organizations, and unions gather in a protest where organization is key. They hold assemblies every day to make decisions.

This blockade is maintained by an umbrella organization, the Multisectoral. It emerged during the 2001 crisis and was spearheaded by Father Jesús Olmedo. Olmedo denounced the extreme poverty in which people live in this city, home to some 30,000 people, where the only sources of employment are public sector jobs and life in the surrounding territories.

At the roadblock, people gather around fires, where by mid-morning food is already being prepared. Every conversation reaffirms the demand: that the reform be annulled. The activity is incessant. On one side, the assembly is taking place; on the other, a letter addressed to the President of the Nation and the National Secretariat of Human Rights is being signed. In the center, around noon, adults and teenagers from the Somos Casira Band burst into a huayno: “You never listen to us, Morales; you always say no, Morales; this is over, Morales; you'll never change, this is over.”

Rosalinda Ancasi then displayed her talent for bringing joy: arm in arm with Eloísa, a community member, she began to dance around the group. After the singing, dancing, and eating, the decisions for Monday, June 26, were announced. It was decided that some protesters would begin a hunger strike. And for Tuesday, a mock crucifixion, like those performed by Father Jesús Olmedo, would be staged to draw attention to the rejection of the constitutional reform and the inequalities experienced in La Quiaca.

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.