Trans and transvestite survivors testified before the court as victims of State Terrorism

For the first time in history, a trial for crimes against humanity focused on the testimony of five trans women and transvestites who were victims of the dictatorship.

Share

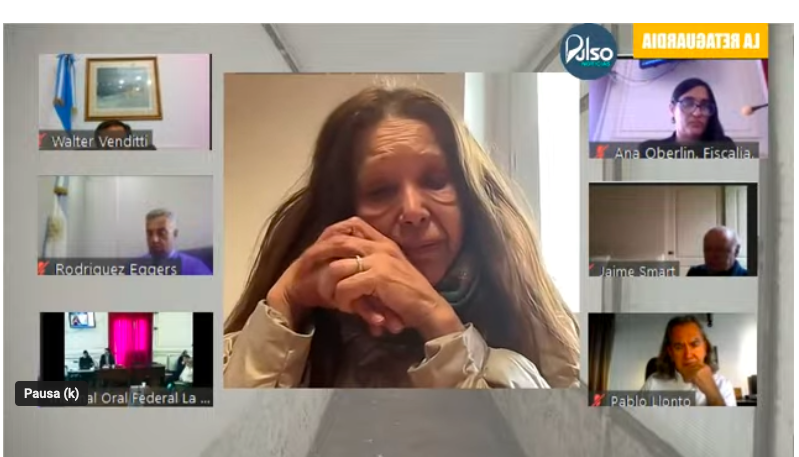

LA PLATA, Argentina . For the first time in history, a trial for crimes against humanity focused on the testimony of five trans women and transvestites who were victims of the dictatorship at the Banfield Detention Center . A transvestite expert witness, activist Marlene Wayar, also participated. On the 101st day of the trial for crimes perpetrated in the brigades of the southern suburbs of Buenos Aires Province, known as the Brigadas case, Carla Fabiana Gutiérrez, Paola Leonor Alagastino, Julieta Alejandra González, Analia Velázquez, and Marcela Viegas Pedro, survivors, testified before the Federal Oral Court (TOF) 1 of La Plata. They told the judges (Walter Venditti, Esteban Rodríguez Eggers, and Ricardo Basilico) that they were held at the Banfield Detention Center , one of the 230 clandestine centers that operated in the province of Buenos Aires under the State Terrorism regime.

In the same investigation, Valeria del Mar Ramírez . Valeria was the first trans woman to become a plaintiff in this case and gave her testimony on day 88 of the trial , where she recounted the violence and torture she suffered, also at the Banfield Detention Center. The defendants are Jaime Smart (who was seen on screen talking on his cell phone while one of the victims testified), Jorge Antonio Bergés, Roberto Balmaceda, Alberto Candioti, Carlos María Romero Pavón, Juan Miguel Wolk, Héctor Di Pasquale, and Luis Horacio Castillo.

From accused to plaintiffs

Today, the five trans/travesti women who testified as victims recounted their imprisonment in what they later learned was the clandestine detention center Pozo de Banfield. They described suffering abuse, rape, and various forms of sexual and psychological violence. Many were forced to work, and the scars of the torture they endured remain to this day. In their testimonies, they remembered many others with whom they shared captivity. They made it clear that they are survivors and that their testimony is also a way to achieve Memory, Truth, and Justice for all those who perished and died young as a result of the structural violence that continued in other forms after the civic-military dictatorship.

The persecution and criminalization they continued to suffer often led to transvestites and trans people being brought before the courts as defendants. Today, after many years, at least some of them have finally been able to tell their stories and be heard in the judicial arena from a different perspective.

The hearing lasted 5 hours and was broadcast via YouTube by La Retaguardia and El Pulso Noticias , two cooperative media outlets covering this trial that began in 2020. It was one of the sessions that drew the largest audience.

“In symbolic terms, today’s hearing was very powerful because part of what we’ve been saying from different perspectives is that during the State Terrorism, the persecution also targeted the trans and travesti community,” Assistant Prosecutor Ana Oberlin told Presentes . “We know they suffered violence before and after the State Terrorism, but that doesn’t negate the fact that they were subjected to the same methods, as these five testimonies from trans and travesti victims demonstrate.”

Oberlin is a lawyer specializing in Human Rights, Gender, and Criminal Law, holds a doctorate in Law and Social Sciences, and is a relative of the disappeared. She believes that "the power of these statements lies in the fact that what they themselves recounted today had not been reflected in one of the most important issues facing Argentina: the trials for crimes against humanity that are currently underway. This highlighted the systematic nature of the persecution of this group, affecting many more people than those we have managed to bring to trial today. In terms of crimes against humanity, I believe there is a before and after. It is the first time that such a large group of victims has been heard. I hope this is a first step and that other courts will consider these claims. May it be reflected and recorded in a sentence as part of what happened under State Terrorism."

To them we were monsters

The first to testify was Fabiana Gutiérrez . She did so via videoconference from Italy, where she fled violence more than 40 years ago. Carla recounted that she was a teenager when she was taken to the Banfield Detention Center.

“One of the nights I started working on the street, I was very young, I lived near La Tablada, I was 14 or 15 years old, I started working on the highway. In 1976 or 1977, I was taken in a private car, I was a minor, I was crying, I was forcibly arrested. It was the first time I had ever been arrested. They kicked me out of the car, they threw me in a place that you couldn't really call a cell.

I was never registered. There were other girls there, and they told me not to say I was underage because it would be worse.

They took off my shoes, leaving me half-naked. To eat, we had to beg them for the leftovers, and we had to pay them with sex. If you want to eat, you have to do that. Doing that meant sucking their penis. Sometimes they'd give you some mate tea or a piece of bread.

I was in there for three nights. I thought they were taking me in for being a prostitute. The first night I met some other women there, and they gave me strength..

I lived opposite the Tablada barracks and at the roundabout I met Claudia Lescano, who is no longer here.

Assistant prosecutor Ana Oberlin asked him if he remembered any other names.

There was Estrellita, La Muñeco, La Jujeña, Paola Alagastino, whom I've known for years. There was Maricela. There are few of us left; many of the girls died. I was arrested several times; that was the first time.

One time they hit me on the head with a stick, Meri was with me. They were kicking us, calling us fucking faggots . Cuqui López, La Perica, Norma Correcaminos. We all had nicknames. I was Fabiana la Cañito. I remember Judith. Luli. I can't remember everyone because it's been over 40 years.

I was a minor when I disappeared. My mother went to the La Tablada barracks to see if she could find out anything about me. The officer told her, "Nothing must have happened to him." I left on the third day the first time.

I didn't want to involve my family; having a gay son was the shame of the neighborhood. I went to my godmother's in Villa Madero. I was tired of being in jail; to them we were animals, but when they wanted sex, they came looking for us. They had psychological problems because they ended up demanding oral or anal sex in exchange for a slice of pizza. We couldn't refuse; if you refused, they beat you to death.

“I came here alone. We get used to everything. We are broken by the things that happened to us and were done to us. That justice is being done for us today is something we have won after so many years of knowing that the girls are no longer here,” Fabiana said, her voice breaking.

You know we worked on the Pan-American Highway, we were run over, and many of us died there. Starting over in another country isn't easy. I was lucky after suffering so much to find people and work in a restaurant. I have the worst memories of my life from Argentina because of the injustices I suffered. To them, we were monsters . You can't understand how they treated us. You have sex with someone and then you hate them the next day—it's incomprehensible. I think they had psychological problems. I saw them bend a coworker's arms. Or when they hit me on the head with a stick, which left me with lasting effects to this day—my head is all swollen, my skull is chipped. A friend took me to Salaberry Hospital. To this day, I still have pain, I lose my memory sometimes, I still take medication. These are things that happened and things that stay with us. As strong as we are, sometimes we break ourselves.

They did whatever they wanted with us.

Paola Leonor Alagastino was the second witness, also testifying via videoconference from Spain. She recounted that she was 17 years old when she was taken from Camino de Cintura, put in the trunk of a white Falcon, in the winter of 1977, and taken to the Banfield Brigade, where this clandestine center operated.

“When they took me out of the vehicle, I thought they were going to kill me. Thank God that didn't happen. But I was mistreated, raped, and beaten with sticks. Some of them were in civilian clothes, and some were wearing not police uniforms, but gray clothes with black boots. We were scared; they treated us badly, insulted us, and said all sorts of things to us. They wanted sex, and if there was no sex, it was beatings .”

They gave us the crust of the pizza. They called us faggots, queers, said we had to die, that we were going to kill them, that we were going to dump them somewhere and who was going to look for them?

We could hear the electric shocks being used on the girls and boys upstairs. It was all hell. They grabbed Fabiana and beat her on the head with sticks. They didn't care about us at all; they treated us worse than animals.

We knew when the soldiers arrived because of the noise of their boots. Thump, thump. They would yell and use electric shocks. We thought it was our turn. There were beatings, rapes, hunger, cold, insults. What we went through was horrible. Besides Fabiana, I remember Yenny, Mónica, Estrellita. But they're not with us anymore. They've all died. There was Maricela, she's still alive. There are only a few of us left. Perica. Cuqui. Marcela, who died two or three years ago. Carla. Once they took me to the commissioner's office. They showed me a photo and asked me, "Do you know her?"

When asked how she knew that the kidnapped women were being subjected to electric shocks, she said that she realized it because of the lamps and lights, which went up and down, and because of the screams.

We were in a place as if we didn't exist.

They wanted sex, and if the person didn't want it, there were beatings and more beatings. It wasn't sex, it was rape. They did whatever they wanted with us. "These faggots have to be killed," they'd say.

After that, I was even afraid to go out shopping.

When I arrived in Spain I was the happiest person in the world because I knew I wasn't going to suffer anymore.

Death was constantly felt

Analía Velázquez, the third witness, testified in person, seated at a table from which hung a banner of the Trans Memory Archive , which remained in place during the testimonies of the next two victims. The Trans Memory Archive is collaborating with this investigation by providing information on trans and travesti survivors who were victims of State Terrorism.

Analía Velázquez, the third witness, testified in person, seated at a table from which hung a banner of the Trans Memory Archive , which remained in place during the testimonies of the next two victims. The Trans Memory Archive is collaborating with this investigation by providing information on trans and travesti survivors who were victims of State Terrorism.

“I was 22 or 23 years old. I was kidnapped from my family's house and taken to the Banfield Detention Center, where I was held on several occasions. They usually took us in the early morning.”

I've endured all kinds of torture, including psychological torture. I've been raped. I've heard horrible things at night. They would say "machine," which everyone knew meant electric shocks, and they warned me it could happen to me at any moment. Once, they made me undress; I even saw a trampoline, all metal. They said it was my turn.

When they wanted, they'd take us out of our cells and make us do stripteases; they wanted us to dance for them. Sometimes they were drunk. I remember being with a female colleague, and they took pictures of us and asked which of us was prettier. I refused. I was very nervous; I've always been a nervous person. And I think her picture was hanging in one of the commissioner's offices. That girl's name was Claudia Lescano; I think she's gone now.

Between 1976 and 1978 I was in that place 6 or 7 times. I remember Paola Leonor, Fabiana, Perica, Claudia Maderna, and Judith.

We weren't just transvestites or trans women; there were other women doing the same thing as us. In that place, we suffered torture, hunger, and cold. We slept on newspaper. They didn't give us food. Although my family took care of me, I didn't eat because I'm very delicate. I was always... angry.

My family hired a lawyer to find out what my fate was, and that lawyer found me. My mother and sister filed habeas corpus petitions.

During the day there were police officers, and at night soldiers. They would take me out in the early hours of the morning and make me bathe with cold water.

Death was ever-present; the screams of those being tortured with electric shocks could be heard. Men, women, ladies, and children wept. "Mom, don't abandon me!" they cried.

All of that happened in the Banfield Well. It was a place like a pigsty.

My given name was Maricela. I had to go to court to be recognized as a woman and as an Argentinian. I've been in newspapers, magazines, on the news, on television. There was a magazine called Así. My family was very scared because people were saying I was a criminal, which I wasn't. The neighborhood was in turmoil. They would fabricate charges against us, they would do whatever they wanted to us.

They would release us in the early hours of the morning. They would take me to a train station, and I would beg for money to get home. I never knew where I was, or which way I would leave.

Sometimes we were stranded in those places for 15 days, or 30, 60, and sometimes even 90 days.

Analía told the court that at one point she had to dye her hair black and leave the country through Misiones to cross into Foz do Iguaçu in Brazil. From there she went to São Paulo, traveled through Rio de Janeiro. Then she returned to Argentina and was arrested. And she went to Europe.

How do I feel after everything I've been through? With many fears, many anxieties that won't go away. Sometimes I don't sleep, I have nightmares. I've lived in very dark places. I have that. I'm very nervous.

Coleen Torres, the lawyer representing the Grandmothers of Plaza de Mayo, asked her if she knew the ages of the children she mentioned in her testimony, whose screams she heard.

-They would be 6 or 7 years old.

Now you're going to find out what's good.

Marcela Viegas Pedro, like anyone about to testify after years of violence, had a trembling voice. She recounted how, when she was about to turn 15, she was kidnapped in Camino de Cintura, Buenos Aires province, where she had fled from Rosario (Santa Fe).

-I was arrested, disappeared, and then I was able to return again. It was between the end of '78 and the beginning of '79. I had to go to work on Camino de Cintura, because of persecution in Rosario.

One of my friends in Florencio Varela, who collaborated with the police, offered me a job at her place. It was a place on the highway with a lot of factories. Every night I had to pay a fee to the patrolman and occasionally perform sexual favors. When they caught me, I said: today it's my turn to perform the sexual favor.

That night was different because when I was inside the patrol car they put bags of onions over my head, took me somewhere, and handed me over to other people, I don't know who. I ended up in a cell. And I remember all the words: Now you're going to find out what's what, faggot.

The next day the ordeal began. Systematically and methodically, every day they came for me. They put a hood over my head. I don't know where I was going. We had a blindfold, and I could peek underneath. They threw me on a bed. They tied me up. And they applied 220 volts (electricity) to me.

They wanted me to tell them the names of the boys I was seeing, their addresses, and what we talked about, but my only relationship with them was sexual; I didn't know their names. Besides that, they also raped me. And then they put me back in my cell.

When Oberlin, the assistant prosecutor, asked her if she remembered anyone, Marcela said she had a very clear image of a dark-haired man with thick eyebrows.

The one who raped me. And the one who impaled me. Because they would put those black sticks up my ass until I bled, and then they would take me back to the cell. I don't really remember if we went up or down.

I didn't know if it was morning, afternoon, or night. The place had only one light bulb, and there was no light. I lost track of time in there. A friend told me how long I was there: 17 days.

I am a person who is 1.77 meters tall and weighs between 78 and 80 kilos and I left weighing 40 kilos.

Thanks to my friend Gina Vivanco, I am here able to tell this story; she is no longer with us.

There were more people inside. Like people my age, 15 or 16 years old.

I had a boyfriend who would drive me around and wait for me on the sidewalk across the street (from where I worked). When he saw them taking me in there, he went to tell Gina; it was the place where she did the arrangements.

The persecution lasted until recently. A few years ago, I received an award for being a trans woman survivor, and since then my photo has been hanging in the National University of Rosario. We haven't had 40 years of democracy, we've had 12, since the Gender Identity Law was passed.

The military leaves, a democratic era begins, but then the crackdowns start. It's a dirty trick that they label us as prostitutes and vagrants. I used to work every night because, being a transvestite, nobody was going to hire me.

It wasn't laziness because I had to do that to be able to pay for my roof, my food, to support myself.

I was left with lasting effects from the repeated impalement. I was on medication. There's a drug that can stop that problem. I was incontinent. I would soil myself. I'm very ashamed.

Slave labor and sexual abuse

Julieta Alejandra González was the last of the victim witnesses. In her statement, she recounted:

“I was 19 or 20 years old, it was in 1977 or 1978. At that time, we were working as prostitutes in Acasusso, San Isidro. They told us to get in a car, we got in, they took us to San Martín. 'Now you'll see,' they told me. They had grabbed me by the hair. 'I'm going to shave your head.' Around dawn, a man came. They didn't want us there.”

In the second cell, after the transfer, they brought us two blue wool mattresses. They had hair and blood clots on them. In the morning, they took us out—it was still dark—and told us to make mate cocido (a type of herbal tea). They asked us if we knew how to cook.

El Negro (Claudia Gómez) and Judith were put to work breaking rocks. In the morning we saw that the place was big. They had two pits where they made us wash the cars. They were muddy, but many had blood inside. I always remember a lot of blood in a yellow Falcon. They made us cook, wash clothes, polish boots. They also sexually abused us.

At one point we heard a girl crying. Then we heard a baby crying. And then we heard neither the girl nor the baby anymore. It was like the baby was born. It had huge lungs because it was crying so loudly. To think we were there for that birth, we were saying afterward. We could hear young people shouting. Girls and boys. When they shouted, it felt like the light was going up and down.

When they took us to have sex, we couldn't refuse. It happened at the police stations too. Another time, I remember that once on the Pan-American Highway, when it was being built, they took us and made all the soldiers rape us, then they let us go; they didn't arrest us that day.

I saw many of them face to face. They groped you all over, your breasts—back then there was no silicone or implants, we used women's birth control pills, your hair grew longer. They'd walk by and grope you. They'd take us to the cellblock after cleaning, in the afternoon. Once I went downstairs and this person was there. "Come here," he said. I kept saying no, no. He grabbed my arm and twisted it. "Yes, you're going," he said, pulling my hair and dragging me into a room. There I had to do what he wanted.

Etchecolatz's perspective

Once, while watching TV, I thought I saw one of those soldiers. His gaze was very piercing. We had him right in front of us the night we arrived. And when the TV focused on him, the look I saw was like going back in time; they were judging him. When they said on TV, "the infamous Banfield Well," that's when I realized I had been detained there.

"Do you know that person's name?" Oberlin asked.

They said it was Etchecolatz. I had him right there in front of me. When they focused the camera on him, his gaze was the same as when I first met him. To me, he was the same person, just older. His gaze was the same.

My mom found me about 15 days after I got there.

Sometimes I hear noises, the baby crying. The screams upset me, especially desperate screams. It's one thing to shout with joy, but a scream of pain is different. It always reminds me of that place.

Marlene Wayar, expert witness

At today's hearing, trans activist, ceramicist, and social psychologist Marlene Wayar testified as a context witness. In November 2020, she testified in the same capacity before the Inter-American Court of Human Rights in the landmark trial for the murder of Honduran trans activist Vicky Hernández .

Marlene explained to the Court some concepts to frame the until recently invisible persecution of the trans community and the social impact of the actions of State Terrorism. She spoke of the profile of the obedient citizen, framed within compulsory heterosexuality, that the armed forces promoted.

“There’s a hierarchical issue at play here. We can see that, as a population group targeted by a specific policy of persecution, they will be assigned to local police because they don’t pose as intense a threat as the perpetrators, who are the union, labor, and student groups involved in specific political activism. We have to frame this within this context, examine the specific gender and sex system,” Wayar explained. “If we don’t frame it within this context, we won’t be able to analyze the relevance, the particularity, and the specificity of this so-called National Reorganization Process. This oppressive force primarily seeks a family man, someone who goes from home to work, who doesn’t hold mass gatherings. Sexual dissidents engaged in prostitution are perceived as a threat to the Christian family system.”

For the trans activist and theorist, the narratives of this era will change compared to those before or after. “People are starting to target trans people to identify them and remove them from their homes. It’s easy to find them on the street, in areas of prostitution. By removing them from their homes, it creates the perception that these people are dangerous, harmful, or contagious, reinforcing the discourse used against political activism .”

Wayar believes that these practices, which linked transvestites and transgender people with ideas of social danger, contributed to a stigma that persists to this day. “This had an overwhelming, massive effect. What we observe in the statistics is that transvestites and transgender people begin to be expelled from their homes as soon as they assume their gender identity, on average at age 13. They begin to experience homelessness. This is an effect of all the prior propaganda that was carried out with such cruelty during the genocidal process,” she explained.

It's important that a trans woman speaks out

He recalled Lohana Berkins's observation that a post-dictatorship generation changed not only their first names but also their last names. In his words: “There is a process underway where masculinities have been subjected to the normalizing force of the dictatorships, conforming to a specific morality, even at the expense of the love that should be given to a son or daughter. And this hadn't been happening on such a massive scale before.”

Wayar spoke about the misuse of police slush funds, about the different uses, both real and symbolic, that were put to those bodies. “With the idea that no one will ask for explanations, the notion is sown that all people connected to these bodies are also liable and tainted. It is important that a trans woman emerge from a concentration camp where she has witnessed atrocities and speaks out. Because it can have an impact. After the military dictatorship, we have had to listen to thousands of accounts. But we don't see that our accounts are of interest. That is why this trial is of paramount historical importance, because it is one of the first where we can hear these voices. We have never had the right to truth, to justice, to memory, or to feel the support that our bodies matter,” she said, and the courtroom applauded.

“Those bodies were almost a game in the hands of macabre people accustomed to the practice of torture. We could have been a rehearsal. They are not bodies that matter. They are cheap paper on which something can be sketched that will be executed with a different quality on other bodies that interest them. We cannot know the reasons because we are not in a position to understand.”

“We don’t have any trans grandmothers. We live an average of 32 years. Later generations haven’t experienced the electric prod because it’s not in the police stations, but we’ve experienced all the other forms of torture that are still in use,” she recalled. “They just killed a comrade in a police station in Pilar. Tehuel has disappeared.”

And before concluding, she shared: “I’ve had to think about how to come to this trial so as not to be seen as a promiscuous transvestite, because you have the opportunity to look at us and judge us. We have a right to life, to legitimate, desirable, and kind life projects. We have a right to memory, truth, and justice. For all the dead women, who don’t even have a headstone, I ask that you recognize them for who they wanted to be.”

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.

2 Comments