"Today we can write other Never Agains with LGBT memory"

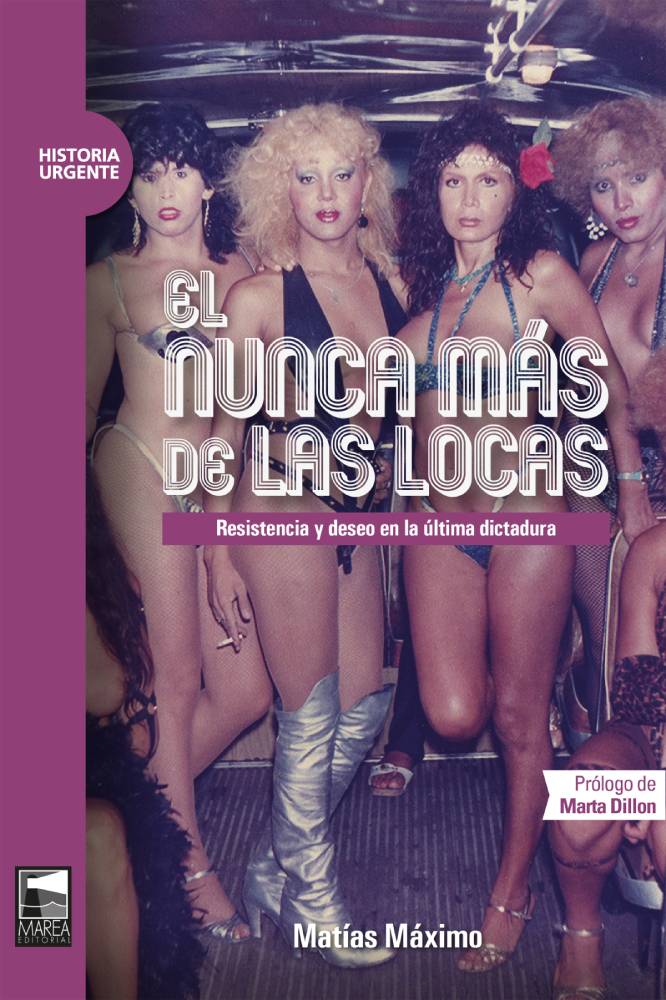

Interview with Matías Máximo, journalist and author of the book "The Never Again of the Madwomen. Resistance and Desire in the Last Dictatorship".

Share

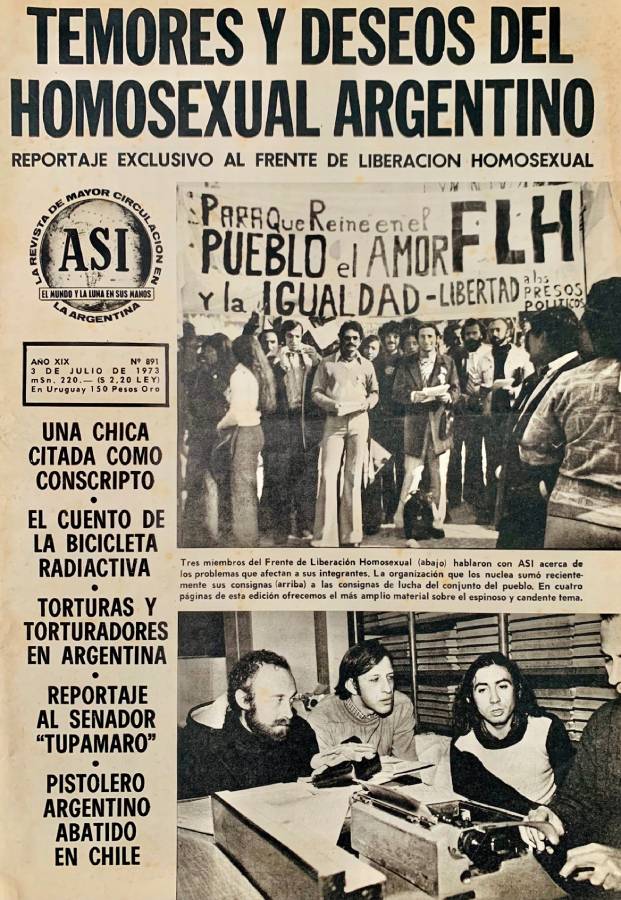

BUENOS AIRES, Argentina. The civic-military dictatorship left painful and deep scars on Argentina. While the violence suffered by LGBT+ people during the State Terrorism , with the exception of isolated cases, the persecution, torture, kidnapping, and disappearances suffered by gay men, lesbians, trans people, and transvestites are not part of official records nor are they recounted in books about this period of history.

“The 40 years of democracy, with some rights achieved, give us the possibility of beginning to incorporate our stories into the construction of history in order to gain other subjectivities that allow us to live freer lives ,” journalist Matías Máximo, author of the book *The Never Again of the Madwomen: Resistance and Desire in the Last Dictatorship*, Agencia Presentes

The book was published by Marea Editorial as part of their Urgent History collection. It was released this year, coinciding with four decades of uninterrupted democracy in Argentina. It recounts the stories of kidnappings and disappearances suffered by the LGBT community during that period and contrasts them with the ways in which they built memory and resisted.

“There’s a saying that history is written by the victors. It’s clear that for many years we weren’t the victors. We were subjected to a chain of persecutions, violence, and destruction by both the state’s terrorist apparatus and by parts of civil society and the Church ,” Máximo explains.

To tell the story of the dictatorship

-What complexities did you encounter when writing this book?

I've been working on this topic for about ten years, since I wrote the first article linking sexual diversity to that period of the last dictatorship. Each chapter of the book focuses on a specific theme. One of the challenges was giving ample time to listen to these survivors, who are now between 60 and 70 years old. They weren't interviews, but rather conversations, encounters that ranged from the ugly to the beautiful. One of the aims was also to talk about desire. Not just to reconstruct history from a heteronormative perspective, to create pornography of pain. The quest was also to reconstruct other possible ways of remembering, where desire and resistance have a place.

-The book's narrative and the selection of stories present a different account of the dictatorship, how did you achieve this?

The narrative proposal is to take a different path. There are several books that approach this period differently: Princesa Montonera *, or Marta Dillon's approach to history in * Aparecida*. There are books that aim to move beyond solemnity to address memory and tell it in other ways. In doing so, the horror is often mixed with moments of celebration, of dark humor. In our narrative, in the way we remember, perhaps due to a survival instinct, there is a constant mixture of dark humor. On the other hand, anyone over 60 who lived in Argentina during those years, whether or not they were part of the LGBT community, will have something to tell you. They will have stories of persecution, of expulsion, of fear of being imprisoned. It was an everyday reality.

Denouncing violence within violence

– What is your analysis of what happened at the time with the CONADEP (National Commission on the Disappearance of Persons) and the lack of registration of diversities in the Nunca Más list?

The Nunca Más report, produced by CONADEP , served an important function at the time. It was completed within a year and was crucial material for the investigation of the Trial of the Juntas (1985) . However, if we analyze it from another perspective, many things were left out. Rather than demanding that they add pages to Nunca Más, I think we can write other Nunca Más reports today . It was a historic work and it fulfilled its purpose. Now, it's strange that the words "gay," "transvestite," "lesbian," or any of the synonyms used for people whose sexual orientation or gender identity deviated from heteronormativity never appear in that report.

We also have to consider the specific conditions, the scene of what it was like to go and file a report with the CONADEP (National Commission on the Disappearance of Persons). There were police at the entrance. How could you approach them to report that your trans friend was missing when those same police officers were the ones enforcing the edicts, meaning they could arrest you for wearing clothing deemed inappropriate for your sex or for inciting sexual activity? There was a lot of fear that they would arrest you for any fabricated reason. Who was going to report these people? How could the report receive these testimonies if, historically, the conditions weren't in place to report these specific types of disappearances?

"It's difficult to build memory when your life is an exile."

-It was also difficult to file a complaint because of a gender identity issue that did not match the document

– The book includes several testimonies stating that for them, democracy began with the Gender Identity Law in 2012. During the dictatorship, identity was not only disrespected, but there were also corrective measures. For example, sexual violence and forced head shaving appear in most of the accounts, and that is specific violence. Many say there wasn't a specific persecution, but there was a system of persecution that began in the mid-1950s and continued in the City of Buenos Aires until 1998 and in the provinces well into the 2000s. All these years, while democracy returned for many, for others, a form of constant persecution persisted.

-Is talking about these issues, about this memory that was until recently invisible, a further step in democracy?

There will always be more rights to achieve, but there is progress from which we can consider other issues, such as the construction of memory. This memory not only enriches democracy but also contributes to the collective memory of all people, regardless of their sexual orientation or gender identity. It's difficult to build memory when your life is a constant exile, when every week you have to move from one boarding house to another or end up in jail. The material conditions for building memory were very different from those under heteronormativity . Do we have the same memory? I don't think so. I'm not interested in the same solemn construction of memory that certain official histories aspire to. I prefer a memory teeming with subjectivities, where the voices of the disaffected have a place.

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.