Gabriel Sepúlveda: how to transition in the age of social media

After documenting his transition on social media, Gabriel Sepúlveda – YouTuber, TikToker and streamer – publishes his first book and challenges some ideas about the dead name: "From Gabriela to Gabriel."

Share

SANTIAGO, Chile . Gabriel Sepúlveda Arcay says it without hesitation: “Nothing is more powerful than stories.” Immersing himself in them, learning from them, telling them, and inspiring others is something he has done time and again. Learning the stories of trans people, particularly Skylar (an American trans activist) and members of the Organizing Trans Diversities Association (OTD) in Chile, made him realize he wasn't alone. And they inspired him to share his own journey.

That's what he's been doing since 2015. As a YouTuber , TikToker, and streamer , he's used his various social media platforms ( @planettas ) to document his transition process in Chile. Over time, his hundreds of videos and posts have taken the form of a diary and a log of each change his body, voice, and relationship with himself and the world have undergone. Thus, unintentionally, he became an activist for the rights and visibility of trans communities and individuals.

The most challenging adventure of my life

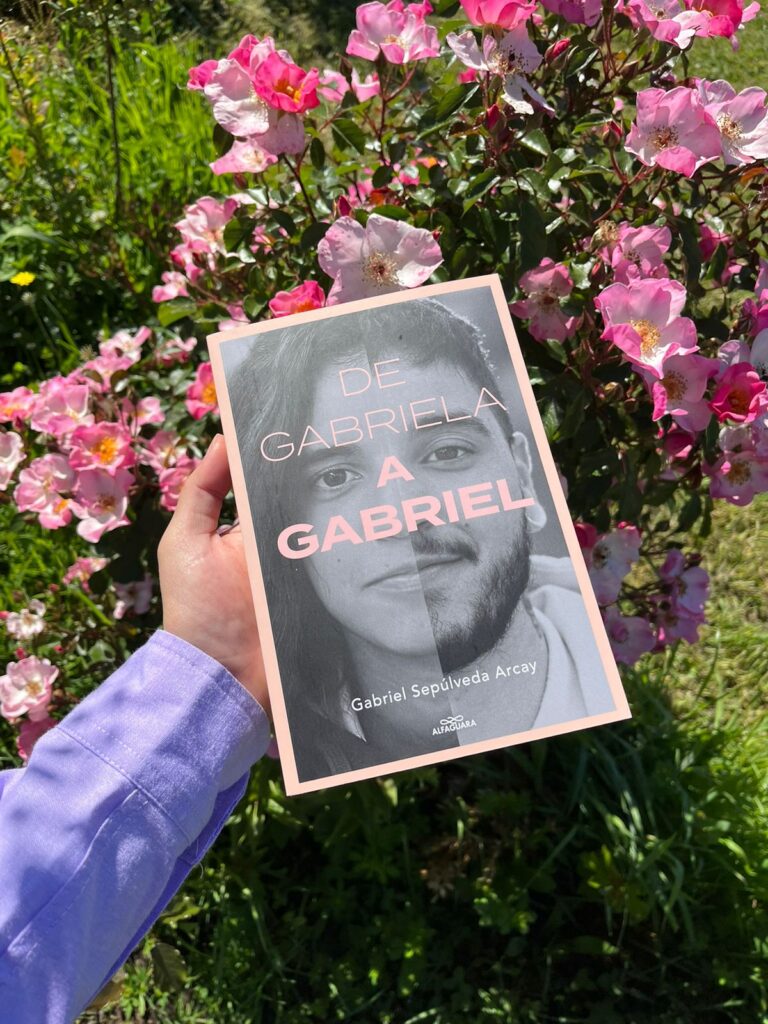

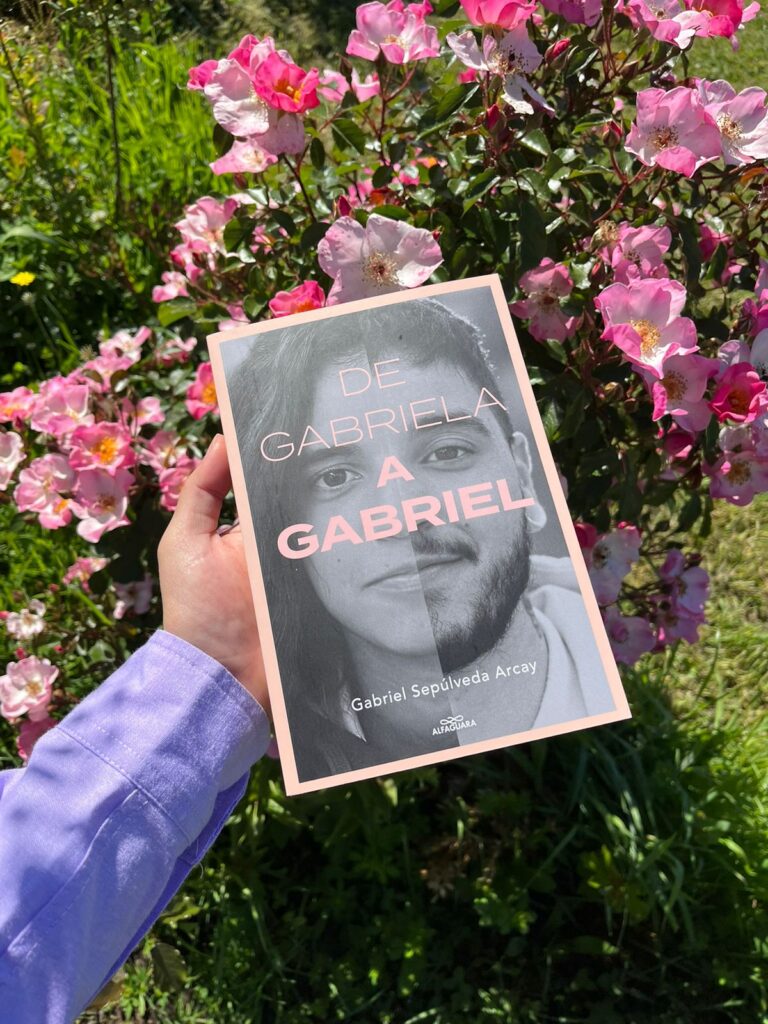

He recently took another step forward and decided to publish his first book, “ From Gabriela to Gabriel” (Alfaguara, 2022). “Recognizing myself and being recognized by others as Gabriel has been the most challenging adventure of my life ,” he says in the opening pages. In a conversation with Presentes, sitting on the other side of the screen from Los Angeles (southern Chile), he affirms that his story has shown him that he is a fighter, resilient, and, above all, brave.

Being a foreigner trans body

Born in Ponce, Puerto Rico, Gabriel arrived in Chile at the age of seven. Since then, he has had to live with his own intersectionality: being a foreigner and being trans. “Feeling like a foreigner is feeling constantly questioned about your difference and for being who you are from the start. Being trans is feeling like a foreigner in your own body ,” he says in one of the book's chapters.

-What reflections do you have on your intersectionalities?

– I see many similarities. For example, in my case, cis passing , or “passing the buck” as a cis man, socially makes you sometimes forget that you're part of the dissident community. The same thing happens to me with being a foreigner. Having been in Chile since I was so little makes you forget your roots a bit, because you try to blend in with the people, with the culture. But ultimately, I'm a trans person, and although I love Chile, I have Chilean residency, etc., and I also take many things from Puerto Rico.

Gabriel also mentions several difficulties that both groups face: bureaucracy, obstacles, segregation, discriminatory treatment, and stereotypes. “Being trans and a migrant in Chile is complicated. You have to do a lot of things for the State, the government, people, and society to accept you for who you are,” he says.

Being who I am and who I was

– In the book you mention that you don't like using the term "dead person" to refer to your previous gender identity . Nor do you use the expression "dead name" to talk about the name you were given at birth…

Yes , I like to talk about my "former identity." I don't talk about a dead person, or a dead name , because that was also me. For a long time, I tried to repress that part of myself and hate myself, but it doesn't make sense to split myself in two and be two different people. I don't like it, because the things Gabriela went through were also things I had to go through to become who I am. Gabriela supported me and helped me, Gabriel, to grow. I don't exist without her, and her memory will always live on in me.

-Also, that allowed you to involve your mother in your transition process…

-Yes, I wanted her to be part of it from the very beginning. I never doubted that my name was Gabriel. I never fantasized about any other.

– Despite that, all the online records about your transition are gone. In the book, you mention that you don't usually look at photos, videos, or anything from the past. How was it to revisit that during the writing process?

–It was a beautiful and difficult process. In a way, I was starting to erase those memories, like in the movie "Inside Out," when Riley starts throwing away the islands. I felt a bit like that, throwing away my memories of Gabriela. In the process of writing the book, seeing myself with long hair or dressed differently, surrounded by people I don't see today, going back in time was a very healing process. I even wish I hadn't deleted so many photos of myself as Gabriela. I regret it a little, but not too much, because at that time I was fully living my transition.

Listening to others

In his personal reflection, Gabriel recalls—though he chooses not to focus the book on it—the bullying and abuse he suffered. In that process, he comments on the similarities with other trans people.

According to the T Survey, the first study conducted in Chile on the trans population, published in 2017 by OTD, 41% of trans people in the country said they identified and began to express their gender identity before the age of five. Furthermore, 76% reported experiencing discrimination. Within their families, 97% faced questions about their identity, 42% were ignored, and 36% suffered verbal abuse.

-When you began your transition in 2015, that survey hadn't been conducted yet. What was it like for you to see those results?

-It was like checking off the results. It's sad, on the one hand, but on the other, it's very good to know that this and other data is available today.

-Something similar, then, to what happened to you when you arrived at OTD…

Knowing that there were people in organizations, that there were foundations, that there were more trans people in Chile at that time when I had just arrived in Santiago to study, was a revelation. The world opened up to me there, and I think the most beautiful thing is building community, because stories help other stories, they help other people.

–People have commented about that on your social media and after the publication of your book.

–Many people have written to me about the book, seeking information, asking for advice, and saying they enjoyed the story. But something that has surprised me is that many mothers, uncles, fathers, grandparents, and other relatives of people with transgender loved ones have written to me, and it's been wonderful to see them seeking help and trying to learn more. That's truly valuable.

– In the book you delve into the importance of building change in community, teaching people about the correct pronouns, and you provide a guide with terms and explanations, such as “gender identity”, “intersex”, “non-binary”.

Look, during the pandemic, my girlfriend (Daniela Ortiz, a psychologist) and I made a booklet called “My Trans Life,” because we knew that during quarantine there were a lot of anxious people, a lot of trans kids, and maybe their homes weren't a safe place. I think it's important to be educational, and that's why I included that guide in my book. Everyone can contribute. We have a moral and ethical obligation, as human beings, to understand and inform ourselves so we don't harm others. I feel, and want to believe, that there is goodness in everyone. When people yell mean things at me, I try to see it that way. This has helped me understand that we, as trans people, have a role to play in helping others become informed.

Let's not settle

–At one point in the book, you mention that as a child you would stay up late with your brother, and when they asked you, "What would you like to be when you grow up?", your answer was "a man." Now that you've achieved that dream, at least socially, what remains to be done?

–I never thought I could be what I was dreaming of, to have this beard, this voice, this hair. Sometimes I still feel dysphoria. I'm still a little short, but I'm very happy with everything I've achieved and also with what I still want to achieve.

-What would that be?

Beyond myself, I want a trans clinic to open in Los Angeles. I want us in Chile to not just settle for changing our name on our ID cards (allowed by the Gender Identity Law). I want better access to physical and mental health care, and above all, to education. I want them to stop killing us, I want it to be safe to be trans here. I'm not satisfied. I feel happy and incredibly proud to be a trans person, of course, but I also know there's still a long way to go. I haven't lost hope. We're just now emerging from our cocoon, socially speaking. People are only just starting to talk about us… There's still a long way to go, but we're starting to take flight.

To fly, like the butterfly that Gabriel has tattooed on his neck.

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.