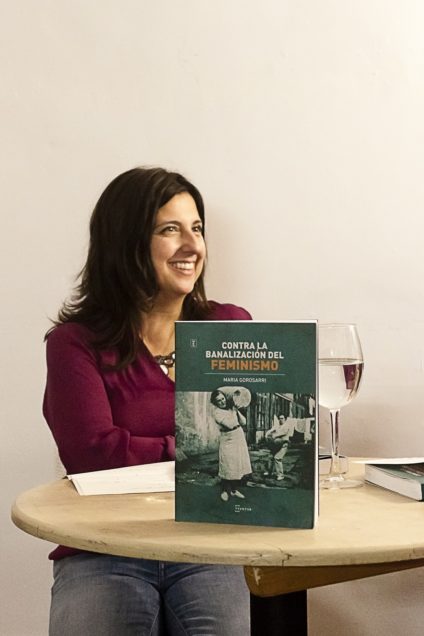

Against the trivialization of feminism

In this interview with Pikara Magazine, Maria Gorosarri, author of 'Against the banalization of feminism', explores the collective challenges to prevent the movement from being emptied of content.

Share

BILBAO. Against the Trivialization of Feminism (Txertoa, 2021) is a book published in Spain, written by María Gorosarri after spending four years in Berlin. “When I left, I was a very radical feminist, and when I returned, I saw that everyone was much more radicalized than I was, and I wanted to know what had happened in this society during those years,” says María Gorosarri , a little while before presenting the book at the Louise Michel in Bilbao.

With degrees in Journalism and Law, and a PhD in Communication, Gorosarri is a professor at the UPV/EHU and often researches historical memory.

What happened during the three years you were in Germany? What was your conclusion?

This is what I've distinguished between feminist identity and feminist consciousness . It's true that feminist identity has reached a level of social acceptance unimaginable 10 years ago: back then, what we saw was what's called the "feminist paradox," where many people agreed with the goals of feminism but refused to publicly identify as feminists. And yet, now I think we're in the opposite situation: everyone understands the goals of feminism, embraces them, and considers them necessary or indispensable for a more just society, hence their self-identification as feminists. However, this doesn't imply any personal or social commitment, neither in our daily lives, nor in our workplaces, nor in the role we play in society.

Has there been an increase in engagement?

We understand the oppression of women on a theoretical level. But we haven't given enough importance to creating an alternative or living the life we should be living, considering our material conditions. I'm referring to the fact that we know we're going to be attacked, but we haven't worked as much on repelling or responding to those attacks. We're still focused on the individual consequences of that violence.

Is a collective reading lacking?

Yes. On one hand, it's more collective, and on the other hand, it's more about raising awareness within that collective, which implies that your life has to change.

"There is a danger of trivializing feminism."

You have written that feminism is an individual subjectivity, but it is characterized as a collective movement.

Historically, always. The question is, in the last 10 years, as it has become more popular, has that been maintained or have political expectations decreased? At the same time, I think identity issues have increased, understanding feminism as identity.

Have political expectations been lowered?

I believe so, not on a societal level, but certainly on the level of individual responsibility for what feminism entails. It's not so much about being a feminist as it is about practicing feminism.

So, is there a trivialization of feminism?

No. I think there is a danger of trivializing feminism ; and realizing this and analyzing it will help us prevent it in the future.

Something banal is something trivial, what is feminism to you?

There's a theoretical framework that almost gives it the status of a science, but feminism is something that has always guided my life, a feeling of injustice. Bell Hooks also says that it's the first sense of oppression you notice in the family, because you notice both social class and race when you come into contact with people from outside your home, but inside your home what you experience is patriarchal oppression, the difference between girls and boys, between men and women.

Yo

You talk about what you noticed when you arrived from Berlin, then there were a few years of mass mobilizations, do you think the feminist movement is now weakened?

In the feminist movement, I've always seen very conscientious people. Now, feminism has become more mainstream, and anyone, even if they're not part of the movement, considers themselves a feminist. And their word carries as much weight as that of someone who's been an activist for years or someone who's just starting out but is doing so seriously. There's a danger that, when talking about feminism or speaking from a feminist perspective, people who don't participate in it or who don't know the movement's history over the last 30 years can empty it of meaning . For example, one of the hardest things to understand is that the new law on guarantees against sexual violence removes the category of abuse from assaults that were historically considered minor under Spanish law. The crime of rape doesn't exist, and yet, within the mass mobilizations, one of the slogans against the Pamplona attack has been "it's not abuse, it's rape," when the crime of rape was abolished in 1995 because it referred to women's honor and was removed for that reason and because it didn't cover assaults against men. In other words, sexual assaults against women were reclassified, instead of as crimes against our honor that harmed our social standing, as crimes against our sexual freedom, which was an important step in 1995, thanks to women like Adela Asúa , for example. And yet, this is disregarded, and the entire struggle is trivialized when we use that slogan: rape doesn't exist, it's sexual assault.

It seems we're constantly doing new things and forgetting about this whole genealogy and the women who have been activists for years. Do we have short memories?

It's normal to have a short memory considering that feminism has taken an immense quantitative step, but I think it's dangerous that anyone can talk about what feminism is, what feminism does... I'm talking about individual feminism, which is what I think really endangers and trivializes the feminist movement.

Christine Lagarde, president of the European Central Bank, and Patricia Botín, president of Banco Santander, now claim to be feminists. Is this a trivialization or a co-optation of feminism—of a concept and a struggle that was causing friction—to empty it of meaning and slap a bow on it?

Yes, that's trivializing it, emptying it of meaning. It's true that for any social group, gaining more members is the goal, but without losing the minimum political foundations.

Should feminism then have an anti-capitalist perspective?

That discourse may exclude certain people. But, without getting into the discourse itself, all feminist measures benefit women in the most precarious situations the most. If the Bilbao City Council acquires apartments for emergency housing for women experiencing violence, the women who will benefit most from that measure will be those who lack access to rental accommodation. Hence the intersectional analysis. The more we delve into feminism, the more we see that it is identified with the class struggle: we talk about the nursing home movement, the domestic workers' movement, and that's because they have embraced the feminist perspective and organized themselves.

You write in the book about Basque, we are in Bilbao and the strength that the feminist movement has here is not the same as in other territories, can this analysis that you make of the danger of trivialization and individualism be applied here?

There are two issues. I'm saying that Basque is not a privilege; privilege theory explains that privileges are benefits or advantages, for example, those men have over women simply by virtue of being men, and the fact that someone speaks Basque doesn't imply any advantage over someone who doesn't, not even here. Regarding the activation of the feminist movement, it seems to me that, traditionally, for example, in Bilbao, there has always been very visible activity with several leading women over the last 30 or 40 years. After the dissolution of ETA, there are parts of this society that feminism has once again stirred up with revolutionary ideals, in what I call the symbolic imaginary; that is, the image of an active militant. Or that every time there is an attack, instead of explaining, what happens is that we're going to recover from all the attacks, and with the patriarchal backlash, we know that we're going to be attacked even more. The image of us being armed as feminist self-defense doesn't seem appropriate to me, because that aggression has already happened and feminist self-defense serves to prevent aggression.

You're referring to the symbolic nature of the images.

Yes, on the posters.

Do you disagree with the more bellicose or combative image?

I understand her, but I don't think it's accurate… because none of those aggressors are afraid of us, no matter how many violent images we post. The question is why, if we declare ourselves feminists, if we've read feminist books, are we unable to strongly defend our rights? It's always said that feminism is a peaceful movement, and it is, strategically, depending on when we act; for example, at night, it's not about defending our bodies, but about getting out of any situation alive. The slogan of the Bilbao festival demonstration [“Tremble, bastards!”] seemed very aggressive to me, and yet the people who participated weren't able to defend that aggression. It seems that, even with aggressive slogans, we don't scare society.

Do we have to be scary?

I don't think so, but if that path is chosen... I think it's more strategic not to instill fear because to achieve anything we need the collaboration of men.

You talk about the patriarchal backlash; in this time that you've been organizing your ideas to write the book, have you seen that backlash?

I measured this in my research on "alleged abuse," and I even published the first article on it in Pikara . I've scientifically measured it in reports of crimes with victims in El País and El Mundo , from 1996 to 2016, to see what the difference is when women report crimes versus when men report them. When women report sexist violence, whether within or outside of relationships, or sexual assault, in the two leading newspapers in the country—which are arguably the most professionally rigorous—the word "alleged" appears twice as often as when a man reports a crime, and this number increases twentyfold after the adoption of equality laws in 2004. I call this a patriarchal backlash. They give us a minimal right to defend ourselves against systemic violence, and in return, what is the reaction? To undermine our social credibility.

In countries like Colombia and Argentina, rights such as abortion are increasing, while they are being lost in countries like the United States.

I interpret this within a European framework. When I lived in Berlin, I was told that gender-based violence, as defined by law, was a problem of Southern Europe, that it didn't happen in Germany. But once they signed the Istanbul Convention, both Germany and France were required to keep records of women murdered by their partners, and it turns out that in Germany and France, the number is more than double that of Spain. Berria has a special website on gender-based violence within couples in the Basque Country, and we can see how many women have been murdered in Iparralde (the French Basque Country) and how many in Hegoalde (the Spanish Basque Country). If we calculate the population of each territory, we see that in Iparralde, the number is three times higher than here.

Trans visibility

Regarding the situation of trans people and the debate on the law, you point out in the book that what has remained intact is the visibility of men.

That's my only criticism of the trans law: it doesn't fight against androcentrism, it doesn't fight against the fact that the common reference point remains the man . When it talks about pregnant people, it doesn't fight against that; that's why I propose, instead of pregnant people, women—who are sometimes pregnant and sometimes not—and pregnant men, which is what breaks down our preconceived notions. If you say pregnant person, we don't see it; we don't acknowledge that a man can get pregnant.

And what about non-binary people?

I'm talking about trans people because I've found an organization like Naizen that already has a vision and a social proposal. In the Basque Country, I haven't found an association for non-binary people. As a journalist, I always rely on social sources rather than personal ones, which is why we participate in society through organizations or social movements, because our demands aren't personal; they affect many different people.

What is your interpretation of all this confrontation and attack against trans people in the wake of the debate on the law?

The way this debate is being conducted is neither constructive nor does it allow us to reach any point of agreement. Tere Maldonado and FeministAlde have tried to organize something along those lines. I, too, have tried to find common ground. Transsexuality is not explained by medicine, transfeminism, or sexology; it is a social phenomenon that we still need to integrate into society.

This book has a very interesting bibliography; it's like an encyclopedia. You name many authors and trace their theories and key moments. In this extensive review you've done, are there any authors you've discovered or rediscovered?

I would cite Simone de Beauvoir 's book

*This article was originally published in Pikara. To learn more about our partnership with this publication, click here .

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.