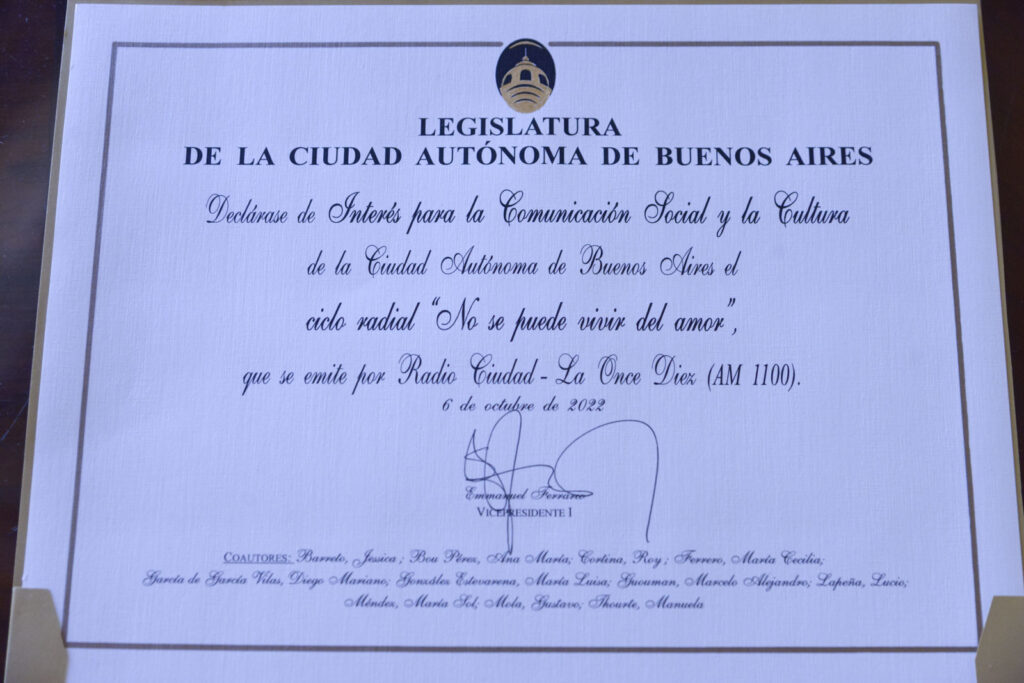

The Buenos Aires Legislature declared the radio program "You Can't Live on Love" to be of interest to Communication

“You can’t live on love alone; it’s a collective force manifested in thousands of daily struggles,” said Franco Torchia, host of this emblematic diversity program, upon receiving the award at the Legislature. We share his words.

Share

BUENOS AIRES, Argentina . The radio program "You Can't Live on Love," hosted by Franco Torchia for more than 10 years on the public radio station of the City of Buenos Aires, was declared by the Legislature "of Interest for Social Communication and Culture."

At Presentes, we celebrate the recognition of this emblematic space for diversity, where we participate weekly with a news overview of diversity in Latin America. And we share the words spoken by Franco Torchia yesterday at the ceremony where he received the award.

"You Can't Live on Love," the radio program I've hosted for the past decade, has received this invaluable award. Accepting it, I reflect on how vast an individual's influence can always be; how subtle the impact of each name can be; how multifaceted and elusive are the personalities that drive change.

From the maelstrom of multitudes of individualities, from the heart of a proper name as identifiable as it is massive, I want to highlight in my training and deformation as a communicator in charge of "You can't live on love" on the public radio of the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires, the know-how and the know-how to get rid of the transvestite-trans experience .

Much more than ten years of radio

Of these ten years of broadcasts, it was from the deepening of the ultra-violated existences of transvestites and trans people that this cycle, which the Buenos Aires Legislative Power highlights today, acquired a definitive character: the furious temperament inherent in the subjectivities that in the words of the Argentine philosopher María Lugones are “liminal”, remain at the entrance and resist expulsion, confined to the threshold of spaces and makers, there, of oblique meanings.

It is this transvestite-trans lesson, scattered across manuals without covers or a single author, that set the tone for this radio program at its inception. It was trans people and transvestites—though not exclusively—who came to it seeking formal employment, yes; social protection, too. But above all, they sought a platform. In the discordant and sub-republican space they inhabit, they transformed this broadcast into a roar with a powerful antenna and an infinite dial. Those of us who produce "You Can't Live on Love" were taught by trans people and transvestites to think, to feel, and to expand the limits of what is audible to a large part of the region and the continent. If this program is known—as it is—in Latin America, today I prefer to say that it is thanks to them, that they embraced it as their own and transformed it into a resounding voice.

Why them, first and foremost? I turn to them to encapsulate in their name the collective proper name I mentioned earlier. They are each and every one of the identities recognized as transient and insurgent, like the gay man whose father would have preferred him to be a "macho," like the lesbian who is still raped to transform her into a "woman." In short, they are those who are still expected not to survive.

There is no definitive identity.

There is no static sexual orientation. There is no fixed status, and there is no single identity card. There is, however, rampant and fully present injustice. There was, indeed, a democracy that only arrived in 2012 for transvestites and trans people, as activist María Belén Correa always points out. And there are, as another extraordinary Argentine philosopher, Diana Maffía, argues, human rights that have been put to a plebiscite, tested both as human rights and as rights in general. Human rights are not subject to a plebiscite, and no person is subject to plebiscite. LGBTIQ+ people are not considered persons until further notice, or until it is proven otherwise.

Of all the lives put to a vote, lives cut short, whose pain finds amplified in our on-air work, I recall the midnight when Praxedes Candelmo Correa arrived at the studio with her nursing degree and her outstanding grades. A survivor of a rape as private as it was public—the one perpetrated against her during her childhood by the male soccer coach Héctor “El Bambino” Veira—Candelmo was unemployed and without justice. Veira, on the other hand, continued to tell stories for pay on TV. Today, Praxedes is a nurse at Argerich Hospital, and today Praxedes has taken her demands to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. That is “You Can’t Live on Love,” that is the transvestite-trans lesson. I am a disciple of its teachings. I took note and began to recognize myself in those life journeys. “You Can’t Live on Love” is a collective force manifested in thousands of daily struggles.

One midnight, I saw Diana Zurco . We had invited her because she was the first trans woman to graduate as a radio announcer in the country. Diana was looking for work, and she found it at LaOnceDiez. Today, Diana also anchors the main newscast on Argentina's Public Television. That is the trans and travesti lesson, and this is what "You Can't Live on Love" means: a collective force manifested in thousands of daily struggles.

Journalism of rebellious scenes

Throughout these ten years, at least once every night, Gabriel Gersbasch appeared on the show and recounted the homophobic murder of his boyfriend, Octavio Romero , who, after announcing in 2011 at the Argentine Naval Prefecture, where he worked, that he was going to get married, was found murdered on the Costanera Norte. On the Río de la Plata, yes. Right within the Prefecture's jurisdiction.

Not a single year went by without our program dedicating countless hours to demanding that the Judiciary and the State administer justice in this long-buried case. Today, eleven years later, the Argentine State has assumed its responsibility before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, and Octavio and Gaby will finally be the protagonists of a series of symbolic acts of reparation. This is “You Can’t Live on Love”: a collective force manifested in thousands of daily struggles.

Dismissals for living with HIV, shortages of antiretroviral medication, homophobic attacks, rampant biphobia, transvesticide and transfemicides happening all the time. Throbbing lesbophobia is now a daily occurrence. The sanctioned torture to which the medical system continues to subject intersex people. The alarming levels of institutional violence; the relentless police repression; the sexual abuse of children and adolescents, like the stories Rufino Varela first shared on the program, which encouraged many victims of priests at the Cardinal Newman School. This is “You Can’t Live on Love”: a collective force manifested in thousands of daily struggles.

Of course, our journalistic raw material isn't solely mortuary. These past years have been dedicated to covering leisure, socializing, nightlife, parties, aesthetics, music, and an overflowing cultural output. Life couldn't exist without its own scenes, and these rebellious scenes, which we've seen grow considerably during this time, are our agenda. Our investigative journalism was and is also a journalism that investigates the images, the sounds, the words, the clothing, and the more or less indelible clues left by the cries launched in pursuit of a counter-normality.

To arm despite disarmament

If there's one thing that structures the lives of LGBTQ+ people, it's that, generally speaking, we're still not expected to survive as we are. If anything, we're expected to survive by being different. Often, the family's challenge—we live in a country, a city, a region where the family can still be a completely unpunished homophobic state institution—the challenge to our ways and identity ceased to be about not existing and became about "existing, yes, but differently from how we exist."

That is the “anomaly,” and it is in this context that I am constantly struck by the thousands of sporting, commercial, tourism, artistic, clothing, cooperative, festival, and support and care initiatives that people—who are still told by families, schools, churches, friends, and traditional media that they could be different—create. They create despite being dismantled. When the suggestion, the insult, the more or less explicit message is not to stop being who they are but to be different, even in spite of it, people resist; there is a powerful pain and a reconstitutive desertion. Every day, those in politics, journalism, education, health, and the public sphere who expect us to be different see our creations pass by. They see what we are capable of doing with what they continue to make of us.

In the middle: lives

In the middle of it all, lives. The lives of those who take to the air and tell us their stories. Lives from Buenos Aires, from across the country, from the continent. All the lives of gay, lesbian, bisexual, intersex, non-binary, transvestite, asexual, and trans people. Bodily defiance and the struggles against fatphobia, ableism, and racial violence. The struggles against hunger. Impossible loves, weddings, secrets. If there's a core I return to whenever I can, it's the simple narration of an LGBTQ+ person's life. There's nothing more powerful, illuminating, and otherworldly than the life of a person urged to be "different" while being who they are. This is "You Can't Live on Love": a collective force manifested in thousands of daily battles.

From day one, the program placed memory—the will to remember, to unearth documents, and to increase the volume of references to the dissident past—at the forefront of its objectives. Over this decade, the program has built an archive that I propose preserving as a fundamental source. If this program is indeed a public policy, its archive has a value that I consider disproportionate, almost intangible. Our lives are made up of erasures, omissions, and supposed insignificance. I urge political power to reverse this historical trend and preserve our conversations, moments, and exchanges. I propose making history with our stories.

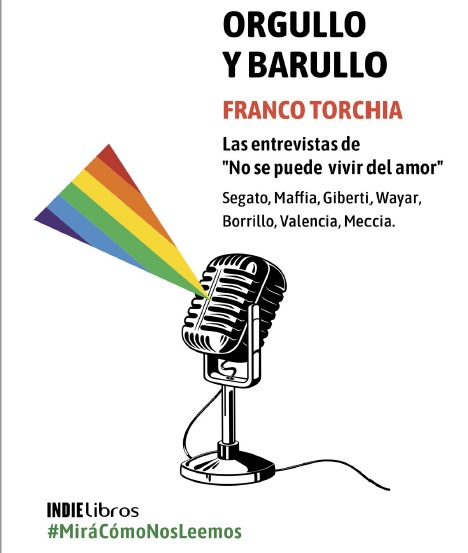

The intellectual and activist voices that have graced the stage of “No se puede vivir amor” (Love Cannot Be Lived)—a few of them, compiled in the book the series published in 2019, *Orgullo y barullo ) —deserve my special thanks. With the admiration of an ideal student, each intellectual and activist who comes to the series challenges my ideas and manages to excite me. I confess that I have ended some interviews with tears in my eyes and renewed anxiety.

The world calls its forced smoothness “sexual diversity.” The world is rough and always diverse. There are no smooth people, and what is truly and astonishingly uniform is cruelty. What, too, reverses that cruelty? Among other implications, declaring our series of interest to Social Communication means that we are of interest. and so displaced from financial support, will become increasingly interesting

Communication and human rights

Journalism specializing in sexual diversity is—if it needs emphasizing—journalism specializing in human rights. However, compared to journalism covering partisan politics, economics, and men's soccer, it ends up sidelined, as if it were a minor public expression. The belief that public interests are the value of the dollar, internal political partisan politics, and the goals of a local derby or a World Cup—which, incidentally, this year celebrates the grandiloquence of a state that legally persecutes, punishes, and arrests LGBTQ+ people, like the State of Qatar—is undeniably a minority view.

To each and every one of the columnists, operators, and announcers who have been with us all this time and continue to be with us today, thank you!!! You enhance our work even more and have always demonstrated a keen understanding of our goals. A huge thank you to Agencia Presentes, Maru Ludueña, Ana Fornaro, and the entire team for enriching our space with your column for over five years!!!

The direct son of an Italian immigrant, who fled a merciless and starving postwar world at the age of twelve, I think that as a child I wanted to stabilize my father's language, a mixture of Calabrian dialect and Ensenada Castilian; and since my father, in this land, had been saddled with such a crooked son, a faggot despite his fringe and sports shirt, I began to speak to myself with a broken recorder and a microphone with no volume. Many years later, I was able to understand that the imperfection of his speech and the deformity of his writing are as imperfect, as deformed, as absurd and charmingly abnormal as our existences, the existence of all of us who thus threaten the classification industry.

I want to acknowledge, with this recognition in mind, language itself. As a child, they called me "Charlatan," I think because I cheated with words. I used them too much. I belong to a segment of the population for whom language is insufficient.

No words can trap us.

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.