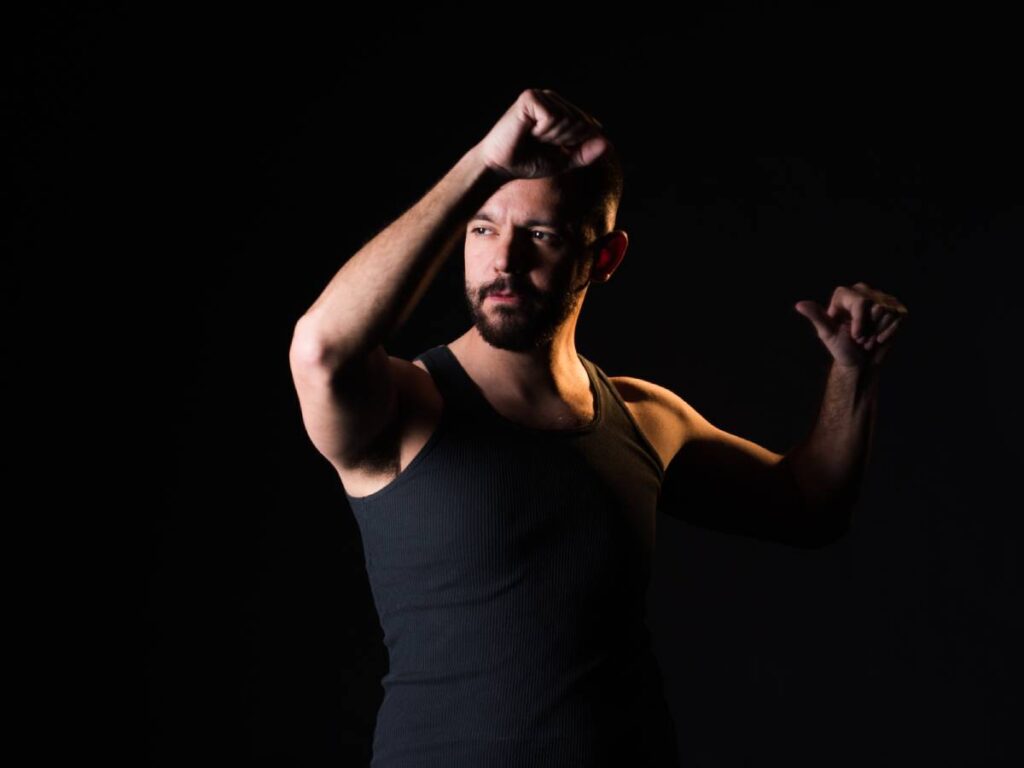

Ale Berón Díaz: “Poetry is always the raw material”

Poet, performer and playwright, after touring Córdoba he will perform a season at Casa Brandon during December.

Share

BUENOS AIRES, Argentina. Anyone who has had the privilege of seeing Ale Berón Díaz on stage, upon hearing his name, probably thinks of many things. Of his powerful voice that seems to contain its own echo, of his intense gaze, of his sustained silences that keep entire theaters on the edge of their seats.

Such is the impact of his stage presence that one might think of his performance first and his poetry second. But when listening to or reading his texts, one thing becomes clear: Ale Berón doesn't write poetry; Ale plays at poetry. And what distinguishes him from all his colleagues is that just when the listener's mind completes a verse because it's certain of what's coming next, the following word completely throws them off balance.

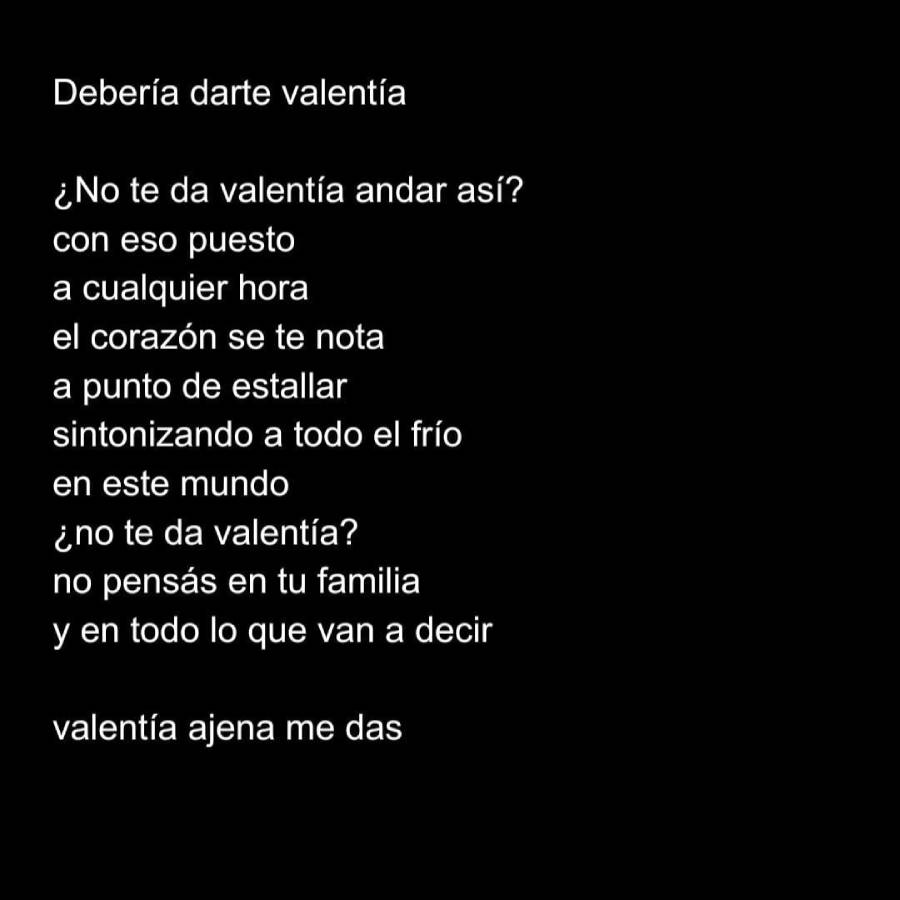

Then “call” is replaced by “love,” “cry” takes the place of “steal,” and “pee” is now “fish.” “Hello / who am I loving? / who do I have the pleasure of meeting?” she asks in her poem “I Loved,” which gives her book its title. “I loved because I wanted to talk to you / I loved you to know / I loved you to tell you / I loved you / to ask you a question.” And so, amid laughter and playful explorations of language, she brings us new images, always speaking to us to ask us a question.

– How did you start writing poetry?

-We use words for everything; to go to the corner store, to go shopping, and there's a certain quality to those words. At some point, I came across that other word, which is like something more, like finding gold. When I was a kid, I had something to say, something that was happening to me in relation to very primal expressions and feelings of love or attraction. I had a text that couldn't be named or put into practice, neither in words nor in action. When I started writing, it was about finding a way to say this. They were very cryptic texts.

– Were you afraid of the reaction of those around you?

I was terrified of how people would react. It was more than fear. And that's how I started writing. At the same time, I began to get involved in the performing arts. When I was about 17, a theater friend told me, "You have to meet Marga." She gave me a piece of paper that said Margarita Roncarolo, Literary Workshop for Teenagers with a Hell in Their Head . I remember thinking, "This is my place, this is where I have to go." So one day I arrived at Marga's house, and it was love at first sight. I did a first workshop for two Saturdays, and from then on, we were inseparable. When I arrived at her workshop, I had all these cryptic texts, and she helped me a lot to find my voice, to think about where I was going, what my meaning was.

–What began as something cryptic, born from a need to say something without being able to fully express it, has become a resource. In your poems, you now play with replacing obvious words with others that unsettle.

-Yes. With Marga, a certain area of power was opened up, allowing meaning to be released and revealed more fully. But it's good that you're bringing this up, that it still contains the seed of something that's almost like a spell.

–In an interview you mentioned that changing words had a playful aspect to exploring poetry. Why do you still enjoy doing that?

I was thinking about how revealing a point of view can be. When you suddenly see something from a different perspective and say, "Ah, I'd never seen it that way." Regarding this play on words, I was thinking about something I could call "points of listening." Just as there are points of view, and a different one can change your life, suddenly hearing something that might sound one way, but can lead you to another point of listening, can create a certain friction and hold you back. Now we're held back in this listening; we're hearing this in a different way, perhaps you've never heard it like this before. Play allows you to discover because you're not focused on the search. You're playing, and suddenly you find a combination where something is happening. The important thing is being able to recognize it, why this works and why it doesn't. Play is always very enjoyable, but you could get distracted and lost in it, and just play for the sake of playing. In the midst of that whirlwind, you have to see, "Something happened here," and stop and take it somewhere else.

From word to body

– How did you come up with the idea of bringing theatrical elements into your poetic production?

-From the first year of the workshop with Marga, we wanted to explore the power of words and bring them to life on stage during the performance. Later, I studied playwriting, and in a typical scene, there's generally a conflict that drives the action; if something happens, it revolves around the power of that conflict. In poetry, where is the conflict? Often it's the absence of it, or it's much more veiled. Then we started embodying it, and it gave the illusion of progressing even without the text containing an explicit conflict. We began to connect with other people who were doing the same thing. At the time, it was very innovative. If there's one thing I really love about this moment, it's that in the early 2000s, if someone organized a festival, they always planned to program bands and theater, but poetry, or lyrics, weren't considered. Today, it's not unusual to go to a poetry event, or for a poet to open for a band, or for there to be a reading followed by a closing set. This whole explosion of poetry is fantastic.

– How did “The world could remember”, the one-person show you have now, come about?

When Amé , my first book, came out, there was a presentation that was a whole theatrical experience, with music, and that first time Patricio Ruiz was also there doing drag. It was a book launch that also contained much more. After the launch came more performances, and that's how the work “Amé” took shape. We started traveling and different venues began to emerge. We also performed it at FIBA, and it was really great because it's a work where, structurally, all the dramaturgy is poems. Then came the pandemic, which canceled a lot of things, but it opened up an unexpected possibility of thinking about what would happen if we isolated all the sound content of the work. That's how the “Amé” album came about with Potable Records. Poetry is always the raw material. I often like to think about the idea of a hologram; there's the poem, you place the poem here and attach a hologram, and all those dimensions emerge. For this second album, which has four tracks, the last one is “The World Could Remember.” This time the gesture was “that it be a work of poetry” and to launch it to that adventure of encountering a body in a space that will unfold poetic content for an hour and a half. Then Casita Brandon appeared, with whom I have a long-standing bond of love, and Casita proposed a whole year of performances, so we're doing a season now.

– How much of your work or your way of performing do you feel is influenced by being part of the LGBT community?

-I could say all of it. Behind all those poems is that little boy who was discovering his emotions and who was very afraid to speak out. I remember very well when I wrote my first poem in which I explicitly used the word "man," and I remember feeling anxiety, palpitations, just from writing it when I was about 17. I remember that poem was titled after an Axe deodorant fragrance because the boy I liked used that deodorant. It affects my work a lot, and it continues to affect it. We are constantly surrounded by situations that people in the community have experienced that are too violent or vulnerable. When you read poetry, you come out of the closet every time you read it. Right now, I'm doing a performance where the first thing I say is "I'm dying of manhood," and from that first line on, there's a bit of dismay; I see it on people's faces as they wonder what's going to happen.

-Is being openly LGBT and making art a form of activism in itself?

-Yes. Going back to that boy who wrote that first poem, when I wrote that poem I had nothing around me to lean on. Now that's changed, but there's also hope in that; every small gesture can lend a hand to those kids who are going through that.

Ale Berón's solo performance will be presented on Sunday, November 13th and Sunday, November 20th in Alta Gracia, Córdoba, and on Sunday, December 11th at Casa Brandon, Buenos Aires . To contact the poet, you can do so through his Instagram: @aleberonn

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.