Argentina: Indigenous organizations from Jujuy and Salta marched in defense of water

The communities demanded water, access to healthcare, education, and housing. They also demanded to be consulted by local governments.

Share

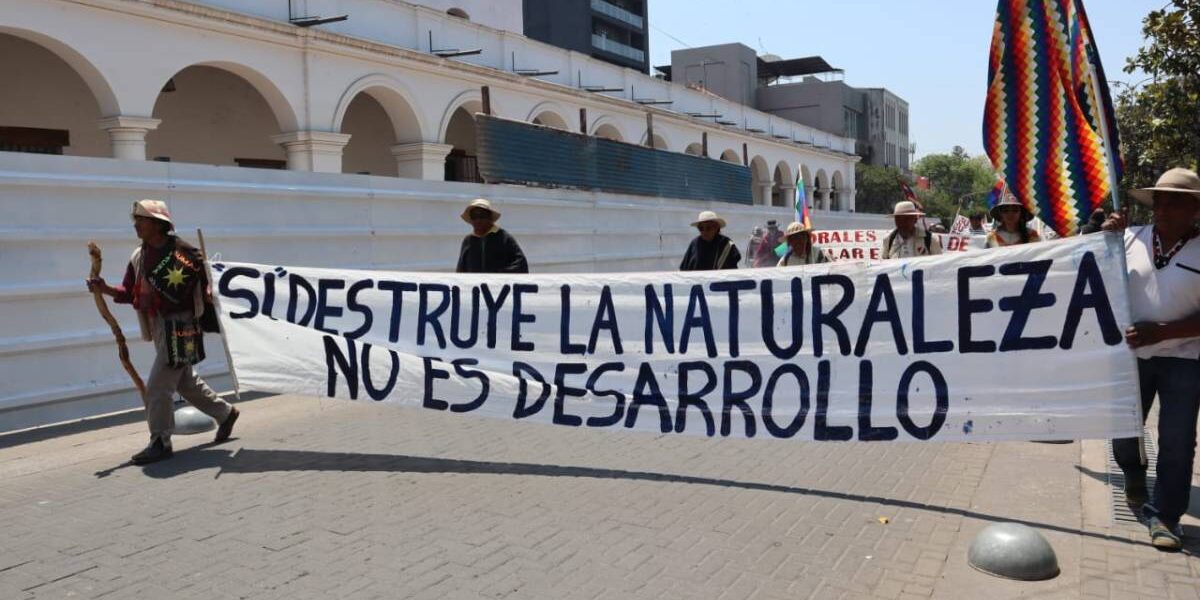

SALTA, Argentina. In the days leading up to October 12, Indigenous organizations from Jujuy and Salta held marches for related causes. In one case, they marched in defense of water and life; in the other, they demanded safe water, access to healthcare, education, and housing.

The Walk for Water and Life began on October 3rd in La Quiaca, on the border with the Plurinational State of Bolivia, and concluded on October 12th in the main square of San Salvador, the capital of Jujuy province. Held for the past ten years, this demonstration aims to draw attention to the environmental damage caused by large-scale mining, which directly impacts water, a scarce resource in the Puna region.

They also denounced the lack of prior, free, and informed consultation on the part of the Jujuy government. And they expressed solidarity with the Mapuche women detained in the south.

Nothing to celebrate

In Salta, Indigenous organizations from the far northeast, bordering Bolivia and Paraguay in the Chaco region, and from the driest areas of the province, held what they called the “second historic march.” They demanded that the provincial government fulfill the promises made in 2020. This mobilization concluded on October 14 in the town of Urundel, more than 217 kilometers from the city of Salta, after a meeting with a government team where they denounced the advancement of a land-use plan for native forests without consulting the communities.

“It is a march for water, for life, in defense of the territories of the indigenous communities of Jujuy. More than five centuries later, on this October 12th, which we say there is nothing to celebrate, today the indigenous peoples still continue under a systematic violation of the rights of our peoples,” said Emilia Liquín, a member of the Indigenous Community of Chalala, from Purmamarca, 66 kilometers from San Salvador.

Without prior, free and informed consultation

The Walk for Water and Life has been held since 2015, but its origins lie a little earlier, when members of the Rodeo community, near the protected area of Laguna de los Pozuelos, noticed certain phenomena that they associated with mineral exploitation.

From there, more than 280 kilometers from the provincial capital of Jujuy, comes Florencia Solís, one of the "grandmothers" who participates in these marches. "We have to take care of our planet," she said in the San Salvador plaza. She's not so worried about waste management, because although it does pollute, for her, "what pollutes the most is large-scale mining."

“Where I live, there are open-pit mines,” he said, referring to the Chinchillas project in the Rinconada department, in the north of the province, which belongs to SSR Mining Inc. Its headquarters are in Vancouver, Canada. “It’s a mine that’s extracting gold, lead, and zinc from Santo Domingo,” he explained.

Next to it is the Laguna de los Pozuelos , which was declared a biosphere reserve. However, “all the shorebirds are being contaminated. There are flamingos, seagulls, coots, and southern lapwings there,” among many others. “Many animals are disappearing because of the pollution from the Pan de Azúcar mine, which also failed to carry out any remediation. Those rivers flow into the lagoon, and that pollution spreads through the soil, the air, and the land.”

Solís's words were recorded by Elisa Barrientos, a member of the Chicha people, who are from the Altiplano region. The site is located partly in present-day Bolivia and partly in Argentina, in Yavi, near La Quiaca.

Barrientos, who currently resides in San Salvador, also identifies the emergence of the need to mobilize in defense of water in the signs of environmental damage that the inhabitants of this area began to notice. Water began to run out in the springs and water sources where they had traditionally obtained it, and dead animals began to appear, among other signs. Then a small group of older women organized the first protest. These are "the grandmothers," the ones who are organizing the march.

Photo: Mariana Mamani

A dialogue of lies

The latest march, the seventh, included communities from La Quiaca Vieja, Chaupiuno, Pozuelos, Rodeo, Abra Pampa, Azul Pampa, Hornaditas, Cangrejillos, Huacalera, Chalala, Rodero, Querusiyal, El Molino, and others. But not all those affected by mining projects were represented.

“Many of our brothers and sisters, due to their lack of knowledge, allowed themselves to be overwhelmed and accepted it. Once mining is established, it's difficult to remove them,” Solís lamented. He recalled that some people signed consent forms for mining operations “and the government is lying,” claiming that everyone did.

He asserted that Gerardo Morales' administration "violates Law 24071 and also Article 75, section 17 (of the National Constitution), which states that prior, free, and informed consultation with Indigenous peoples must be carried out. However, he disregarded everything. He only spoke with the rural commissioners or some community members," and then claimed that "he spoke with the entire community."

Barrientos emphasized to Presentes the unequal nature of the confrontation. “It seems like a fight against giants because there is no right of reply, for example, in the media; the State changes the production model without consulting the communities.”

Photo: Mariana Mamani

The voices that go unheard

Elisa Barrientos agreed with Solís that there had been no consultation. And if there had been, it wasn't prior, free, and informed, she maintained. The law, she recalled, establishes that Indigenous peoples must participate “and know what it's about, what they're going to do with their territory, what they're going to do with the water, how they're going to do it. And that hasn't been done. From one day to the next, as always happens here in Jujuy, the machinery appears opening roads, the trucks appear, and years later, the officials show up to inaugurate things. When you don't even know what happened, when it happened, who signed it, and everything else.”

On the other hand, Liquín denounced “the infiltration by the current municipal government (in Purmamarca) in collusion with the governor of Jujuy.” He recounted that police officers infiltrated the communities “to continue encroaching upon and seizing our territory.” He also stated that they enter homes and intimidate women and children into leaving.

During the march, the organization reported that they were harassed by the police along the way. "From the beginning of the march, they photographed and filmed us constantly. In Humahuaca, they interrogated a girl in an inquisitorial manner; the girl was very frightened. And in Purmamarca, they tried to interrogate some children."

In defense of Pachamama

Florencia Solís vows to “continue fighting to the bitter end against these governments in power,” which are no different when it comes to mining. “They are governments complicit with transnational corporations,” part of the “murderous capitalism that continues to advance across our Abya Yala. Especially here in our province of Jujuy,” she explains. Just like “in those times of colonialism, when they came to plunder our natural resources, now they are doing the same: dispossessing people of their land, their place, their town. Most of us live off livestock, from cattle, llamas, and goats. That is our work,” in addition to spinning and weaving.

Solís asserted that the Jujuy government is trying to deceive the Indigenous communities, threatening them to silence them. “But I will never be silenced. I've already said that I will continue fighting to the bitter end, even if they send in the Gendarmerie, the Police, or the Army. I'm not afraid of anything. My goal is to fight for Pachamama, because we have a great responsibility to her. We know that the earth, the planet, is a big house that we must cleanse.”

Incidentally, she said the march is a wake-up call for Morales. “It seems he doesn’t even clean his own house. He doesn’t realize that we have to keep the big house as clean as the house where we live.” On the other hand, “he completely ignores this; he talks about Pachamama, but he does the exact opposite. He betrays Pachamama; he’s a governor who, in one way or another, violates the rights of the Indigenous communities who live here defending our land.”

Photo: Mariana Mamani

A cause for everyone

Florencia urged everyone to defend the land, saying, “This cause belongs to all of us.” She especially emphasized to future generations that they must “defend the water” because without it there is no life.

Barrientos noted that another water dispute is also taking place in the Salinas Grandes area, involving the establishment of mining companies. He asserted that there was no prior consultation in this case either.

Liquín said the march was also to “denounce the continued advance of lithium extraction, the demands of mining companies, and the fact that the governor recently traveled to Europe and the United States to hand them over to us. To hand over our natural resources. We are ancestral defenders of these resources because we understand that without water there is no life. We understand that we cannot develop in our own communities if they take away our territories; even now, more than 500 years later, they continue to take away our territories.”

And Barrientos drew attention to “creole colonialism.” Behind it all are the great powers, he warned, “they always have been; colonialism is the foundation. What needs to be deconstructed today, in addition to patriarchy and capitalism, is colonialism. And this colonialism allows companies to enter the territory as if they own the place and do whatever they want without prior and free consultation.”

Drinking water

In the neighboring province of Salta, on October 11, members of the Autonomous Union of Indigenous Communities of the Pilcomayo (UACOP), whose territory is in the extensive Rivadavia department, more than 500 kilometers from the provincial capital, arrived at "the Pichanal crossroads", halfway there, to carry out a protest remembering the non-compliance with government promises.

At that point, where other communities from the General San Martín and Orán departments, which are also part of UACOP, joined in, they began blocking traffic on National Route 34, demanding that Governor Gustavo Sáenz come and explain why the 21 points agreed upon in the first march, held in December 2020, were not fulfilled.

These points relate to access to safe water, health, education, land, housing, and respect for their culture. Of all these, the most urgent is access to water, especially now that summer is approaching, and in areas with high temperatures.

After three days of protest without any response, the communities began a march south, which they announced could take them all the way to the Casa Rosada (the presidential palace). They only traveled 38 kilometers south, to the town of Urundel. There, they were informed that a government team was traveling to meet with them. The meeting took place on the side of the road, on a windy day.

Let the officials listen

A makeshift table was set up, behind which officials sat, including the Minister of Health, Juan José Esteban, and the Minister of Social Development, Silvina Vargas. Community leaders reiterated their long-standing demands: they have no water, or if they do, it is “not good” for human consumption; in some cases, they must fetch it in jugs from kilometers away; many families live in precarious structures made of sticks and plastic sheeting; health workers do not reach them; and bilingual education is not offered in the schools (some of which are far away).

The responses left a bad taste in the mouth. Officials acknowledged problems with some of the wells they were drilling because they didn't find potable water. In other cases, Minister Esteban pledged to monitor existing wells, given reports that worms were found in the water, as Abel Mendoza, head of UACOP, confirmed.

These communities are scattered across a vast territory, where safe water comes from wells that must be dug to great depths and whose cost exceeds the economic means of the original inhabitants. On the other hand, in the case of urbanized communities, they are generally located on the outskirts of towns, where services are also unavailable.

Julia Gómez, coordinator of the Honhat Le Les community, located in the town of Embarcación, told Presentes that they are requesting a water well. The community is located three kilometers from the town, and the piped water service does not reach them. This request has been ongoing for ten years. For now, the municipality brings them water with a tank and a tractor, but it is not enough "for planting. There is nothing to plant with."

Regarding housing, another key point in the demands, the news wasn't good either. In 2020, the government had committed to building 1,000 homes. Now, they've only committed to building 150 prefabricated wooden houses between now and the first months of 2023, with another 150 to follow.

A forum for dialogue

According to reports following the meeting, the government team did not come to engage in dialogue, but rather to present a proposal. Therefore, after listening to the officials, the protesters held a meeting in which, although they emphasized that the proposal did not meet their demands, they chose to accept it and end the protest.

In the end, the expressions of both sides revealed the different perceptions of the meeting. “It’s a working group where we listened to the proposals and where we also began working on concrete responses ,” said Antonio Hucena, the province’s Secretary of Institutional Relations, who almost celebrated, clarifying that they were carrying “the governor’s decisions to work with our brothers and with the communities.”

“Here we are, not very satisfied of course,” said Abel Mendoza from the other side. He maintained that with what happened with the promises of 2020, “there is a fear that another deception will occur.” He said that this time they will closely monitor what is being done and will react when there are breaches of contract; “we are not going to wait around for long.”

Perhaps more knowledgeable about the laws than his counterpart in Institutional Relations, the Secretary of Indigenous Affairs, Luis Gómez Almaraz, emphasized the importance of dialogue: “For the state to implement efficient public policies, their participation and consultation are essential. This will be the only way we can be effective and move forward in fulfilling our commitments,” he stated.

Health and education

Many of the UACOP communities are covered by the ruling issued in February 2020 by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, which ordered the granting of community land titles to 400,000 hectares of the former state-owned lots 55 and 14, and mandated the implementation of projects to improve the quality of life and redress the harm caused by state inaction to the Indigenous peoples who have ancestrally inhabited this territory. The ruling expressly orders that all of this be done with prior, free, and informed consultation.

Julia Gómez, a participant in the first Historical March, which reached the city of Salta, recalled that they “never” received a response to their requests from two years ago. “It’s very sad, us begging them to give us something,” she lamented.

She said that her community doesn't have health workers. Another community member, Mabel Gutiérrez, told Presentes that on Saturday morning, the day after the protest, they had received a visit from health workers.

Regarding education, the children of Honhat Le Les (Children of the Earth) attend the Fray Francisco Victoria school in the nearby neighborhood, which lacks a bilingual teacher, although they were promised one for next year. Generally, the children complete secondary school, but that's where their studies end, the coordinator explained. There are no resources to support higher education, so most stay there and work odd jobs on local farms because "there's nothing else."

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.