Sex work, prostitution and oil in Patagonia: what a Mapuche anthropologist investigated

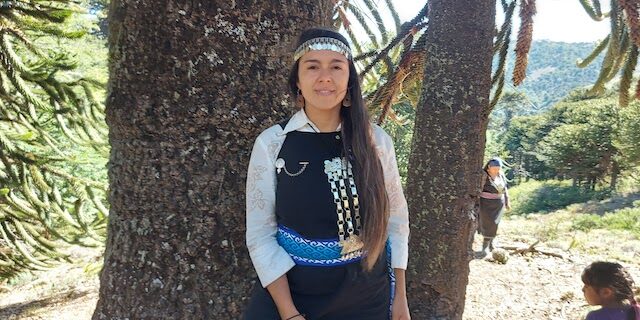

Meli Cabrapán Duarte is a Mapuche social anthropologist. She investigates the many facets of extractivism in Patagonian oil-producing regions. "It not only affects the environment, but also transforms social relations."

Share

For years, Mapuche social anthropologist Meli Cabrapán Duarte has been researching prostitution in the context of oil extraction. She seeks to "question those things we take for granted," such as the relationship between trafficking and oil. For her, it is necessary to investigate "what the underlying issues are," while also "pointing out that there is conflict." Furthermore, she emphasizes that extractive projects not only affect the environment but also transform social relations.

Migrant women in the Patagonian night

Her mother wanted to name her "Meli" (four, in Mapuzungun), but she was registered as "Melisa." She was born in the city of Bariloche (Río Negro Province, Argentina). However, her "tuwvn" (territorial origin) is Gulumapu, a territory near the Villarrica volcano in Chile. She is part of the Lof Newen Mapu, 15 kilometers from the center of the city of Neuquén. This community is organized as the Xawvn Ko Zonal Council of the Mapuche Confederation of Neuquén . It comprises 12 other lof, all located in the area now known as "Vaca Muerta."

Cabrapán Duarte studied Social Anthropology at the University of Río Negro and earned a doctorate from the University of Buenos Aires . She specialized in gender studies and feminist anthropology. Her forthcoming book, Women of the Night and Oil Workers: Transitions between Economy, Sexuality, and Affects , will be published by Todos Editorial, of the Patagonian Institute of Humanities and Social Sciences Studies (IPEHCS) of the National Scientific and Technical Research Council (CONICET).

-How did you get involved in these topics?

I worked with Dominican and Colombian women who had migrated to Patagonia, especially to tourist cities like Bariloche. I was researching migration issues and, coincidentally—or perhaps not so coincidentally—how they were entering the sex trade. Many were responding to a demand from sex tourism, although there was also local demand.

They weren't required to meet so many requirements to stay in the country. Then, with the passage of the law against human trafficking, they began to be required to have visas to enter Argentina. They started to move around, and cities scattered throughout Patagonia, linked to the oil industry, emerged as common destinations. For my doctoral thesis, I conducted research in various cabarets that were still prevalent or operating clandestinely. Later, I became more involved with the daily lives of a group of women.

Patterns of inequality and resistance

-What are those lives you investigated like?

I maintain and defend that the situation of the majority lies somewhere in between. These are women who are not politicized, who don't identify as sex workers, but neither do they consider themselves victims of exploitation . Although they do experience various situations of coercion and violence. This occurs within a system of economic precarity and labor exclusion, not only for being women but also for being migrants and Black . In general, what leads to this situation are webs of inequality structured by capitalism, racism, sexism, and patriarchy .

-How do women resist in these contexts?

-Especially through the networks they create: networks of friends, family, godmothers, because they also maintain these reciprocal bonds—children, aunts. In the case of the oil-producing region, this challenges the exclusive portrayal of the violent man. Men have also played and continue to play a role in these support networks. Which doesn't mean they are based solely on solidarity or selfless reciprocity.

-You were talking about foreign women (Dominican and Colombian). Did you also observe indigenous women?

That question relates to my current interests. In the oil-producing region, or what's known as Patagonia, there's an exclusion of Indigenous women from the sex trade. This is even reflected in the interests of those in power who seek to exploit women's bodies. We can analyze how this relates to racist beauty stereotypes . At least in southern Argentina, this elite sex market also defines and reinforces which bodies, beauty stereotypes, and sexualities are demanded and commodified. This also happens in other contexts. For example, in the Peruvian and Ecuadorian Amazon, the migration of Indigenous women to cities tends to lead them to these spaces of labor integration or coercion.

Extractivism and prostitution

-How do you relate extractivism to prostitution?

When one examines these areas of common resource extraction, it's essential to consider their historical context . We must examine what has transpired over the decades, the years. Because with the oil-producing region of northern Patagonia, it's a well-known fact: prostitution has always been closely linked to oil exploitation. Prostitution and oil have a direct relationship. These highly male-dominated settlements generate and alter the original dynamics, because the relationships that could have existed between men and women are completely overwhelmed by this massive male presence.

When oil and gas deposits are discovered and exploration begins, workers settle in nearby areas, in urban centers. That's why Añelo , often mistakenly called "the heart of Vaca Muerta," has seen its population grow at incredible rates in the last seven years. The same thing has happened in other cities.

-Since when have these dynamics been occurring?

-Oil was discovered in Comodoro Rivadavia Plaza Huincul , Neuquén, dates from 1918. That generated the first exploration. That first masculinization began there. The state-owned company YPF (Yacimientos Petrolíferos Fiscales) had its own cabaret from 1922-24 until the late 1950s. It was called " La Casita de Chapa " (The Little Tin House). How can we not see this issue as naturalized in that example, even during the process of regulating the abolitionist legislation?

Extractive and heteronormative

-How are homosexual identities represented in these contexts?

Extractive industries are characterized by being highly heteronormative. There are also open secrets about non-heterosexual relationships. But these oil-related relationships are not recognized as homosexual due to this mandate of masculinity. It doesn't generally appear as a representation, although it does appear as a rumor or something that is stigmatized or ridiculed.

-What was it like for you to work in the field as an indigenous woman?

I was much younger when I started going to places like that. I think I was somewhat naive or innocent, assuming that being in a bar having a beer with friends was the same as being in a place like that, which is actually the same thing, only with different kinds of interactions. Back in Patagonia, which was my homeland, I didn't attract much attention from men; I was just one of them. There, the desired bodies were generally those of foreign women.

In other contexts, like in Ciudad del Carmen, Mexico, I was the foreigner. Based on those same stereotypes and on the skin pigmentation scale, I appeared a bit lighter, perhaps, than I did in my own country. This suddenly created a different kind of connection, or even prompted questions about whether I was working there.

-What findings and/or questions did these investigations leave you with?

I always try to draw attention to the need to question things we take for granted. While it's true that oil and prostitution have historically been linked, it's interesting to consider the new forms this relationship is taking, what lies beyond that . I think we need to ask ourselves what power structures are behind this . But asking these questions doesn't mean we should ignore the conflict: that the damage to nature, and all these extractive projects, generate transformations that affect more than just the environment. It's not just extractivism that causes ecological damage; it also generates multiple other transformations. I think we should also address these multiple impacts, these multiple forms of damage, which are all interconnected.

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.