Interview with Gracia Trujillo: Queer feminism for everyone

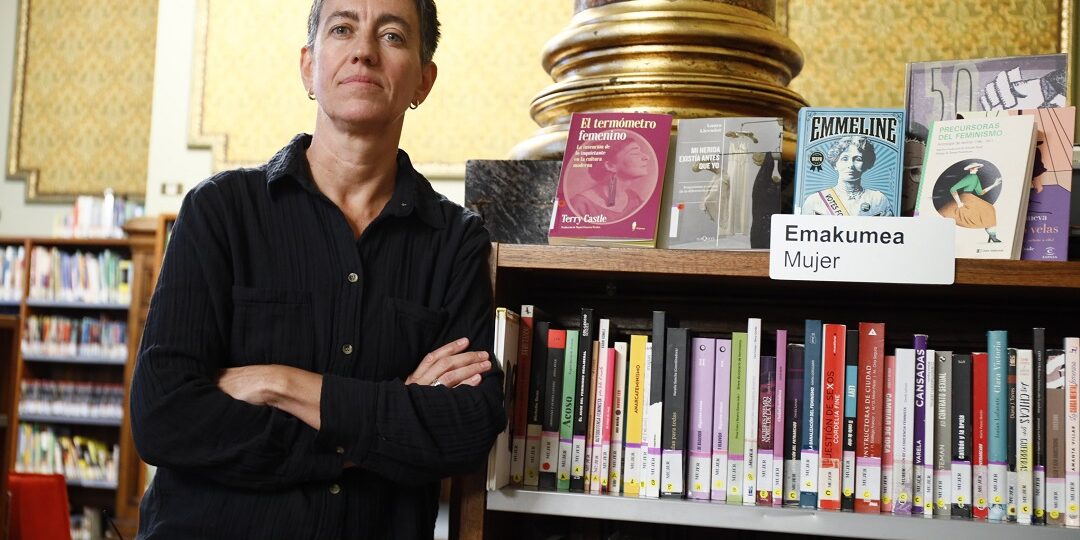

Gracia Trujillo, queer feminist activist and professor of Sociology, analyzes what is happening with feminisms and identity logics, regarding her book: Queer feminism is for everyone.

Share

“My queer is to stop hearing my friends and loved ones say that, at this rate, with so many conflicts and such violence within feminism, they’re going to stop calling themselves feminists.” In *Queer Feminism Is for Everyone* (Catarata, 2022), Gracia Trujillo , queer theory and reviews activism in Spain, with the intention that her essay will serve “to foster dialogue, build bridges, and rebuild our feminist networks (and affections).”

In Spain, the term "queer" appeared in the first half of the 1990s, thanks to groups like La Radical Gai and LSD. In 2009, at the feminist conference in Granada, it burst onto the scene with force. Why, in 2022, a book explaining the basics of this movement?

Clarifying what “queer” is, its fundamental theoretical contributions, and the history of queer in Spain is necessary to situate those interested in the topic within current debates, as well as those who may not have had the time or resources to learn about it. The book is also a response to the backlash from the trans-exclusionary feminist sector, which is reverting to speaking in biological terms of sexual and gender binarism, and in essentialist terms of “woman.”

Which of those contributions do you highlight?

Questioning normality, gender binaries, and heteronormativity is key because, as Monique Wittig , there are realities that cannot be seen through a heterosexual lens. I also emphasize the importance of delving into an intersectional perspective; I agree with Ochy Curiel that considering all the axes of oppression that shape our lives gives feminism much more radical power. Paying attention to bodies, sexual and gender identities, and gender expressions—queer theories and activism have created a space for those other lives, bodies, and subjectivities that were not being addressed by more traditional feminism.

Biology is not destiny

A sector of feminism, which also includes feminists with a tradition in the equality movement, is now advocating for sexual difference, even on a biological basis. What is your take on this?

Attempting to return to a more rigid definition of womanhood now is not only impossible, but also a poor political strategy , given the collective experience, both theoretical and practical, and the lessons we have accumulated within feminisms—in the plural—in responding to the urgent needs and complexities of social reality. Returning to black and white thinking, besides failing to address this complexity, takes us back decades; feminism had already made it clear that biology is not destiny. Furthermore, this stance is working in tandem with the far right, who assert that girls are girls and boys are boys, and that the idea of girls having penises and boys having vulvas is completely untenable. Along these lines, a friend observed that, in recent years, feminists denounced the transphobic bus organized by Hazte Oír, and that today, some of them would be riding on it. "We are moving beyond identity politics, in the sense that we are thinking more about what unites us than about our identities, which often isolate us." CLICK TO TWEET

Do you think that return to "black or white" might have something to do with how the queer movement has heightened the issue of identity?

queer political practices and theories, a critique has been raised regarding the construction of identities when these exclude subjects, while simultaneously considering them strategically. Gayatri Spivak as “strategic essentialism.” What is happening is that there is an open war against these grassroots, queer , anti-capitalist, anti-racist, autonomous feminisms, which the trans-exclusionary feminist sector cannot control . For years, we have been overflowing not only the streets but also identity politics , in the sense that we think more about what unites us than about our identities, which often isolate us. This is not to say that identities are no longer necessary. I believe that, as political fictions, they still serve us strategically in many ways. Even today, we still have to say that we are women, migrants, lesbians, trans, racialized, and so on. On the other hand, the trans-exclusionary reaction has a very important class and racial component because, in my opinion, the anti-racist struggle is in queer feminisms, transfeminists (with our collective errors and learnings), much more than in that trans-exclusionary feminist sector which, in general, is more institutional, academic, and is based in spaces of power, more concerned with defending its privileges than with listening to and attending to other realities that are far from those areas.

Sometimes I get the feeling that queer claims copyright on the axes of oppression, when many of the "historical" feminists who do not adhere to that current today already questioned what they called the "heterosexual norm" in their time, especially lesbian groups, or forged their political culture in anti-capitalist parties.

Queer activism and theory didn't invent anti-capitalism, but they did bring the intersectional perspective to the forefront, highlighting that not everyone has the same material resources, skin color, age, abilities, or educational level, among other potential axes of oppression. This intersectional perspective has also allowed us to question our own privileges based on class, whiteness, citizenship, or any other kind. Queer activism is fracturing the discourse of the more traditional left, which continues to claim that these struggles are divisive, that diversity is what prevents the left from progressing, and which still believes that they focus on the rights of the working class while we focus on the rights of gay, lesbian, bisexual, and trans people—in other words, on what's least important . As if we weren't also working class or couldn't be unemployed! Or as if the most precarious jobs weren't usually held by migrant women, often undocumented! A fundamental aspect of the trans, queer queer struggle is the questioning of the classic subject of the labor movement: the white, cisgender, heterosexual, male family man. We are in every struggle because we are everywhere, and because, being so, everything affects us: cuts to public healthcare, education, social services… We didn't reinvent the wheel; we have many activist legacies, and we must acknowledge them. That's why I place so much emphasis on our political genealogies in the book. I talk about currents, which often overlap, about conflicts within activism, which haven't always been in agreement; even the term "queer" is an umbrella that has its holes, that doesn't cover everyone equally.

The calls for unity among feminists, which appear scattered throughout the essay, are appreciated.

Some might think I'm being overly optimistic or naive; I hope I'm not the latter… When I was writing the book, I was thinking about all the comrades, both men and women, with whom we can still talk. By this, I mean that there's a group with whom, sadly, we can no longer do so, because they've aligned themselves with hate speech, and that's a line that cannot be crossed. Many people are asking what's happening with " queer ," why there's so much conflict within feminism—it's all so incomprehensible… That's why I think it's time to negotiate the disagreements we have on issues we can still discuss and to look for common ground. The enemy out there knows exactly who they're targeting: us, who, meanwhile, are embroiled in very sterile and, at times, very violent struggles.

Aren't the margins getting too crowded after so much talk about "living on the margins"?

When we talk about living on the margins of this heteropatriarchal, racist, and classist system, it's important to consider the context. Living on these margins isn't cool , fun, or modern, because it implies having been expelled from the center, which represents nothing less than the possibility of a livable life, free from violence, with rights, freedoms, legitimacy, and visibility. The margins are violence, as Leslie Feinberg in her book *Stone Butch Blues* , recently translated and highly recommended.

What value, then, is there in reclaiming the margins if, in addition, feminism calls for putting the urgent issues at the center, such as care or a dignified life?

Bell Hooks 's work, Feminist Theory: From the Margins to the Center , now almost four decades old, advocated for placing important issues at the center and observing what is happening around them. Since the 2008 crisis, with the 15M movement, and now with the pandemic, the urgency of care work has intensified. We have focused much more on who is caring for whom, on the juggling act required to maintain caregiving at home , on the precariousness of those who have lost their jobs, and on the return to the closet of LGBTQ+ people who have had to move back in with their families. These issues must truly be at the heart of our political practices. However, the margins can have another meaning. When we reclaim them from queer , it is to highlight that this system neither includes us nor do we want it to include us; that they should not count on us in a heteropatriarchal, racist, classist system that generates so much violence. For example, in the 80s and 90s, autonomous feminist movements never advocated for women fighting to enter the military; what we wanted was to abolish it. Or, when same-sex marriage was debated, the Queer Working Group, the Barcelona Lesbian Feminist Group, and a few other collectives raised their voices because, for us, marriage wasn't the priority. We came from a whole struggle that began in the 70s for free love, for other forms of sexual and emotional relationships, for other types of families… Why force ourselves into a monogamous institution that, historically, has been a prison for women? Why not a civil partnership law at the national level, which, by the way, was never achieved? Obviously, we weren't fighting against people who wanted to get married or against the legal progress that same-sex marriage, adoption, and parentage represented. What we wanted, from more queer , was to keep our sights on the horizons we were moving towards. And we're still on that path. Ultimately, I believe the term "margins" encompasses two distinct concepts. First, it means advocating for the rights and freedoms of those excluded from the system; and second, it means choosing to remain on the margins, as a metaphor for a critical perspective on a violent system that perpetuates inequalities and with which we refuse to be complicit or collaborate. Furthermore, from the margins, the system is more clearly observed, allowing us to continue transforming it radically.

queer groups share a number of elements, such as their critique of identity politics and its exclusions, while also making strategic use of identities in specific situations.” In practice, haven't they actually served to reinforce those identities?

“ Queerness ” raises a critique of the sex-gender binary: there aren't two boxes—man/woman; masculine/feminine; heterosexual/homosexual… There aren't just two options, but an infinite number of possibilities; the same person can change their gender identity or sexual orientation, or not, and all options are legitimate. Thus, identity proliferation is a political strategy that challenges the binary, because it leaves out a multitude of realities, life experiences, and embodied experiences. The alternative proposed by queer is to articulate sexual and gender identities so that they are as porous and inclusive as possible, while not losing sight of the fact that they are intersected by other axes of oppression. The idea that “ queerness ” aims to dismantle identities and leave us feeling as if the ground has been shaken, as they say in Latin America, is a common misunderstanding. What we do is critique the exclusion generated by certain identity constructions, keeping in mind that we still need them. "I'm interested in identities conceived in collective terms, which can be summarized as articulating them to take to the streets and demand rights or protest against violence and discrimination." CLICK TO TWEET

Indeed, identities are presented as tactical detours, but, as Tere Maldonado maintains, it seems we've become entrenched in them, as if they were an end in themselves. In this interview , Sejo Carrascosa warned that "we're not questioning the root of the problem: compulsory heterosexuality," adding that identity politics "are the equivalent of neoliberal policies and constrain us because they stem from a completely non-intersectional approach." He says that "we can be hyper-identity-driven, but our inability to play with identities has led us to lower the bar for our demands."

I completely agree with both of you. We can think of identities in individual and collective terms. I'm interested in the latter, which boils down to articulating identities to take to the streets and demand rights, protest against violence and discrimination, or simply to say: “Here we are, we exist, and we claim our right to be free and live as we please.” The important thing is that we activate these identities, which, moreover, can change throughout our lives, as can the political priority we choose to give them when it suits us: being a woman, a lesbian, from a rural area, working class, disabled …

I think that, in practice, the explosion of identities has prioritized being over doing, and that this has contributed to compartmentalizing struggles and demobilizing them. Almost by default, the authority to have an opinion or to act is questioned for those who are not what they are opining or acting on. Let me explain: it seems that anyone who isn't a lesbian, trans, a sex worker, a person of color, or Muslim can't interfere with sexual orientation and gender identity, with prostitution, with decoloniality, or with patriarchy as a central ideology in all monotheistic religions, including Islam. What do you think?

It would be interesting to analyze how feminisms have been dealing with this. It's true that if you're not the main political subject of the struggle, your participation can be questioned; you're only expected to listen and collaborate. I believe that those subjects should have the main voice, but taking it to extremes excludes alliances, empathy, and solidarity. Sometimes, out of fear of being spoken for, of being taken under someone else's tutelage, we reach extremes that, in effect, prevent us from uniting in struggles that have much in common. Having said all that, I'm not making a staunch defense of "queerness . " Like any philosophical and political current, like any constellation of activism, it has its weaknesses. Nothing is perfect. What I do think is important to emphasize, in relation to the beginning of your question, is that queer is not an identity; it's not so much about being queer as it is about feeling queer, if anything. queer politics , or a verb, a queer or queerizing , in the sense of traversing, transforming, transgressing, as we said in the transfeminist manifestos.

Reflecting on “ queer ” in education, you point out: “To the extent that we, as teachers, bring that passion [the pursuit of knowledge], that love for the ideas we are capable of inspiring, to the educational space, that space becomes a dynamic place where social relations can be transformed and where the false dichotomy between the internal and external worlds of academia disappears.” Isn't this placing too much individual responsibility on each teacher? Isn't it overlooking the segregation of schools, the cuts to public education to prioritize private and charter schools, and the Vatican agreements? Isn't it overlooking the fact that improving the educational space requires, first and foremost, appropriate government resources and projects?

“ Queerness ” is not detached from material issues; the intersectional perspective places them at the center of our gaze and our daily practice in schools. When I talk about trying to transform the educational space, I think in collective terms: in terms of networks and teacher coordination to try to think and educate beyond binaries and certain school practices that are so naturalized they go unnoticed. Without resources, it's difficult to change anything, but it's also difficult without a network and a more coordinated and aware teaching staff. Or without collective mobilization outside the classroom. The educational institution itself harbors a great deal of hostility toward these other discourses and ways of doing things. The queer perspective in education questions the dichotomies we live with: theory and practice, mind and body, high and low culture, academic success and failure, academia and activism… In that sense, universities in Latin America, for example, have much more contact with the street; they are centers of thought more connected to social realities and activism in general . Furthermore, the queer approach offers analytical methods that are key to preventing violence against non-cisheteronormative bodies and gender expressions. We need to try to create more horizontal spaces, to use other discourses and methodologies… which is very difficult because we run into the same problems: insufficient resources, very high student-teacher ratios, precarious teaching staff, a public education system that we must continue to defend against neoliberal policies and the advance of conservative forces without having the best working conditions… Sometimes, the temptation is to say: “Look, I teach my classes and…”.

queer theory places great emphasis on recognition and symbolism, something that neoliberalism easily co-opts—just look at Pride . What about redistribution?

In the book, I address the debate on redistribution and recognition between Judith Butler and Nancy Fraser ; there can be no recognition without redistribution, they go hand in hand . Recognition of trans people is fundamental, for example, through name changes on ID cards, but so is the redistribution of material resources so they can access employment, housing, education, healthcare, and specialized, high-quality support, among other things.

*This article was originally published in Pikara. To learn more about our partnership with this publication, click here .

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.