Indigenous communities in Paraguay demand solutions to the drought and lack of drinking water

The Campo Loro community says they only have enough water for two months and are demanding that the Paraguayan Chamber of Deputies declare a state of emergency.

Share

ASUNCIÓN, Paraguay. The prolonged drought resulting from climate change affects us as a global population, but these levels of impact are not uniform or equal.

In the Paraguayan Chaco, for indigenous communities like Campo Loro of the Ayoreo People, the lack of water is a historical problem. And it has worsened even more in the last 8 months due to the lack of rain.

Decades without water

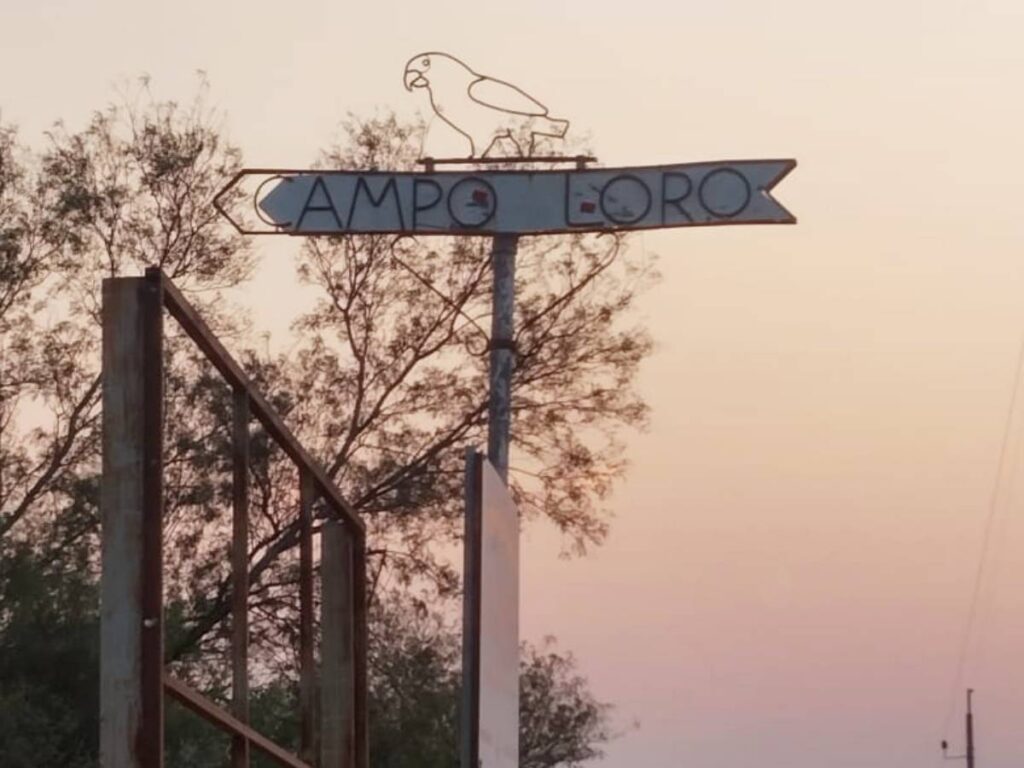

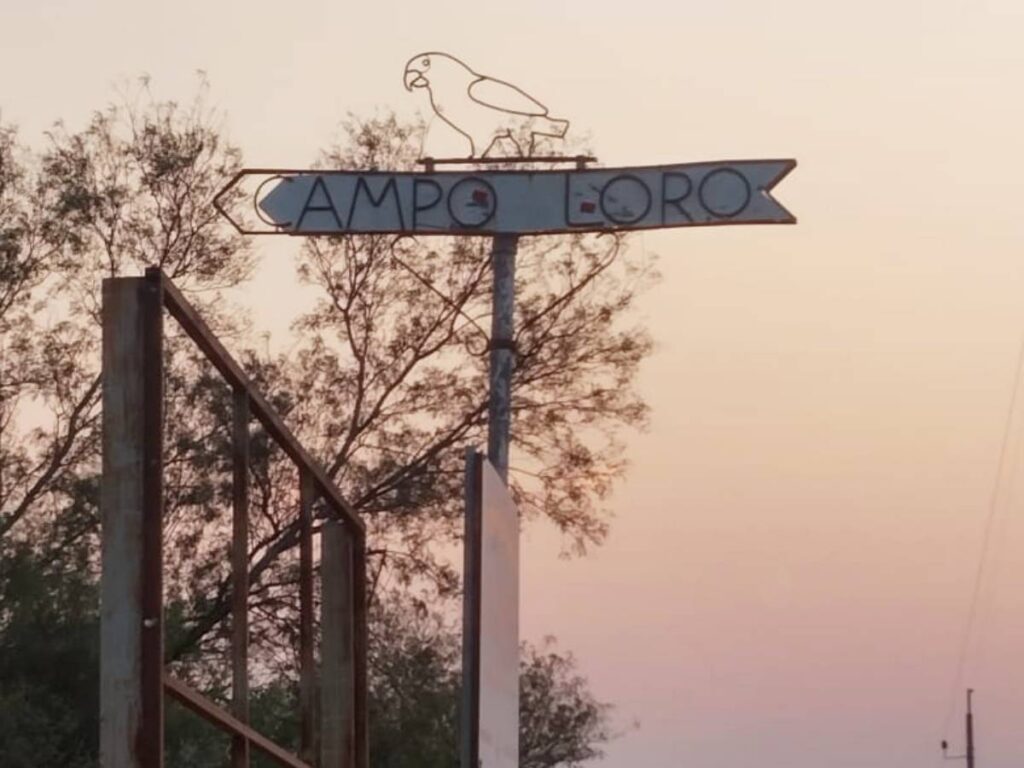

Located 300 kilometers from the capital city of Asunción, in the Filadelfia district of the Boquerón department, are the Campo Loro community, . This community comprises approximately 1,000 people of the Ayoreo people Pueblo Ayoreo – Iniciativa Amotocodie , live in 13 settlements .

In Paraguay there are 19 indigenous peoples and 5 linguistic families; Guaraní, Maskoy Language, Mataco Mataguayo and Zamuco, the latter is the language of the Ayoreo People. According to the last Indigenous Census carried out in 2012: there are 371 indigenous communities in the Eastern and Western regions; 117,150 represents 2% of the population, and the Ayoreo indigenous people represent 2.2% of that total.

The Campo Loro community was founded in 1979 by a church called New Tribes Mission. Although the community has a land title, for 43 years they have lived without a potable water system guaranteeing their right to access water. Families depend solely on rainfall.

Drought and lack of water

Probably most of us reading this material can, for example, wash our hands simply by turning on a tap or faucet, and we can take a bath at least once a day.

Perhaps pouring a glass of water or preparing a hot mate isn't part of our daily concerns . This isn't a uniform reality. It's certainly not the case for the Ayoreo people in the Paraguayan Chaco.

The climate is characterized by being arid and very hot. It can easily reach extreme temperatures of 40 to 45° Celsius or more in spring and summer. Even in the middle of winter, the maximum can reach 28° Celsius and the minimum 14° Celsius.

The drought in Paraguay has now lasted three years. This year, crops and seeds have been lost, just to name a few of the consequences. However, there are indigenous communities that are now struggling to find ways to even secure enough water for drinking. Other needs, such as bathing, are not considered essential.

“We only have enough water for one or two more months”

María Cutamiño and Marina Picanere are Indigenous women from the Ayoreo people. Both are mothers and artisans. They speak with concern about the difficult situation they face due to the water shortage in their community, Campo Loro. Indigenous communities living in the Paraguayan Chaco have consistently denounced the neglect they suffer at the hands of the state. However, they only achieve agreements through protests as a form of pressure.

“Access to water is difficult in the community, and the drought is affecting us. The National Emergency Secretariat (SEN) hasn't visited us; we need water and food too. The governor's office visited us a month ago, but that's not enough and it's going to end. We've started drinking water from the reservoir, and that's causing diarrhea. We only have enough water for one or two more months,” said Marina Picanere, an Ayoreo artisan.

“There’s hardly any water for bathing. There’s no water,” says María, holding her youngest son, Mauro, who is one year and seven months old. I suppose she was telling him to stay still because she was speaking to him in his language, Zamuco. “The leader is always asking the governor and the municipality for water, but they bring us very little, I don’t know why. We have a reservoir; the animals get their water from there too,” she explains, almost searching for the right words in Spanish to describe the situation.

At that moment, his partner, Sereda Picanerai, arrives and joins the conversation. “The most urgent need in the community is water. We suffer from this every year; it hasn't rained in the Chaco region for eight months. The animals need water too. Without water for us, human beings, it will be difficult, and this is the need that 250 families are experiencing,” he explains.

Towards a more serious situation

María, Marina, and Sereda all point out that it is often through the leader's efforts that they have been able to access a little water. However, their main concern is that sometimes the government delivers water tankers that are not safe to drink, and even cause stomach problems.

The community also has dams and a water filtration system. Given the lack of rain, the situation could worsen considerably starting in October. They estimate that the current water supply will only last for another two months.

Maria and Sereda are constantly thinking about other Ayoreo communities. They say that almost all Ayoreo communities suffer from a lack of water, and that the situation is even more dire for families living north of Filadelfia. “They suffer much more. If they submit a request, the governor's office hardly ever responds; if they do, it takes three days or a week, and the water travels more than 100 kilometers,” they explain.

Need for more cisterns

During the previous administration, the National Housing and Habitat Secretariat (SENAVITAT) built 93 low-income homes with 5,000-liter cisterns for the Campo Loro community. This did not benefit the entire community, and some of the cisterns have already broken.

In addition to the private cisterns, there are three other community cisterns, each with a capacity of 25,000 liters. These provide a total of approximately 75,000 liters of water when filled; two are located at schools and one at the community church. Water is then carried from these cisterns to the private cisterns when it is available.

In Declaration DGCCARN No. 1112/2016 , the Secretariat of the Environment (SEAM), now known as the Ministry of the Environment, approved the Environmental Impact Study for the construction of 228 rural homes. Each home has two bedrooms and measures 41.25 square meters, for a total area of approximately 9,405 square meters.

“However, Resolution No. 1,788 of 2017 from Senavitat , which approves the number of beneficiaries, indicates that the total number of homes would be 96, a difference of 132 fewer homes than the previous document. The same document authorizes the disbursement to the company Arquitectónica SRL, responsible for the work. It details that the total amount to be paid by the institution is G. 5,901,609,740, and the contribution from the beneficiaries (the indigenous people) is G. 310,611,039 (several housing programs of the Ministry of Housing and Habitat stipulate a State contribution plus a counterpart contribution from the beneficiary family),” the report by Roberto Irrazabal for the dossier “ Right to the Future” points out that this situation is not new and that it had already worsened during the COVID-19 pandemic. Two years later, the conditions have not improved in the slightest.

Maria and Marina urgently need a solution that will allow their children and family access to clean drinking water, a basic human right. They also express the need for more cisterns and a potable water system. The Campo Loro community and the Ayoreo people are just two examples of Indigenous communities in Paraguay currently crying out for water.

Departmental emergency

The department of Boquerón is one of the territories with the largest indigenous population in Paraguay. They represent 60% of a population of 85,000 inhabitants, both indigenous and non-indigenous.

According to the Meteorology and Hydrology Directorate of DINAC (National Directorate of Civil Aeronautics) for the month of July, a marked water deficit of up to 100 millimeters was observed in the northwest and south in recent months, in well-defined areas with moderate to exceptional drought conditions over the last six months. Their report indicates that extreme drought could affect territories in Boquerón (18.55%), Alto Paraguay (22.17%), and Presidente Hayes (0.58%).

The governor of the Boquerón department, Dario Medina, declared a state of emergency in the territory at the beginning of August due to the critical situation. Specifically, the districts of Filadelfia, Boquerón, Loma Plata, and Mariscal Estigarribia were included.

Legislators Edwin Reimer (ANR-Boquerón), Basilio Núñez (ANR-Presidente Hayes), Marlene Ocampos (ANR-Alto Paraguay), and Enrique Mineur (PLRA-Presidente Hayes), representing the departments of the Eastern Region, presented a bill on August 4th. The bill, which declares a state of emergency in the departments of Presidente Hayes, Boquerón, and Alto Paraguay due to the drought affecting the entire Chaco region, will be debated in the lower house's advisory committees.

To date, it is expected that the Chamber of Deputies will declare an emergency for the department of Boquerón and assist the communities most affected by the drought.

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.