Food sovereignty: The land still feeds the children of Bolivia

The indigenous peasant territory of Raqaypampa promotes agriculture to achieve food sovereignty.

Share

This story is part of the journalistic series Drawing my reality, #IndigenousChildhood in Latin America , co-created with indigenous and non-indigenous children, journalists and communicators from the Tejiendo Historias Network ( Rede Tecendo Histórias ), under the editorial coordination of the independent media outlet Agenda Propia .

Where is Anayra? Anayra is the protagonist of this story, though she doesn't know it yet. She's had enough time to dress in the traditional clothing of her village, Raqaypampa, a Quechua indigenous territory 220 kilometers southeast of the city of Cochabamba, Bolivia. It's not the uniform she'll wear to school, but her teachers have convinced her to wear it to present some drawings she and some of her classmates have made about their territory and traditional food.

However, right now, at 11:45 a.m. on this Thursday at the end of March, Anayra isn't there. Where is Anayra? The school breakfast, which looks more like lunch, is about to be served to the students. And she's not there. And she can't miss it, because this snack isn't just any snack: it's one of the initiatives undertaken by the Raqaypampa autonomous government to combat malnutrition, which, according to a 2019 study commissioned by the local government to researchers from the Medical School of the Universidad Mayor de San Simón, threatened the children of Raqaypampa between the ages of 5 and 12.

Luckily, Anayra is already here.

Photo: Santiago Espinoza.

The impertinent face mask

Anayra Rojas Albarracín is one of the few people wearing a face mask in Raqaypampa. This is significant. The country has just emerged from the fourth wave of the coronavirus pandemic, but remains under a state of health emergency, and the use of surgical masks is still the norm. At least, it is in the cities. Not so in the countryside. In towns like this, it's much easier to find Barcelona jerseys than face masks.

Anayra is 11 years old, and the only thing her face mask reveals are her shy, bright, black eyes, which hint at a nervous laugh in the journalist's presence. The face shield is the only "unusual" item on her body. From head to toe, she is dressed as a woman from Raqaypampa: black and white sandals, a blue skirt with horizontal embroidery, a pleated pink apron with two embroidered stripes, a white silk blouse with the chest and cuffs covered in sparkling embellishments, and a white hat with a sequined crown and wool tassels.

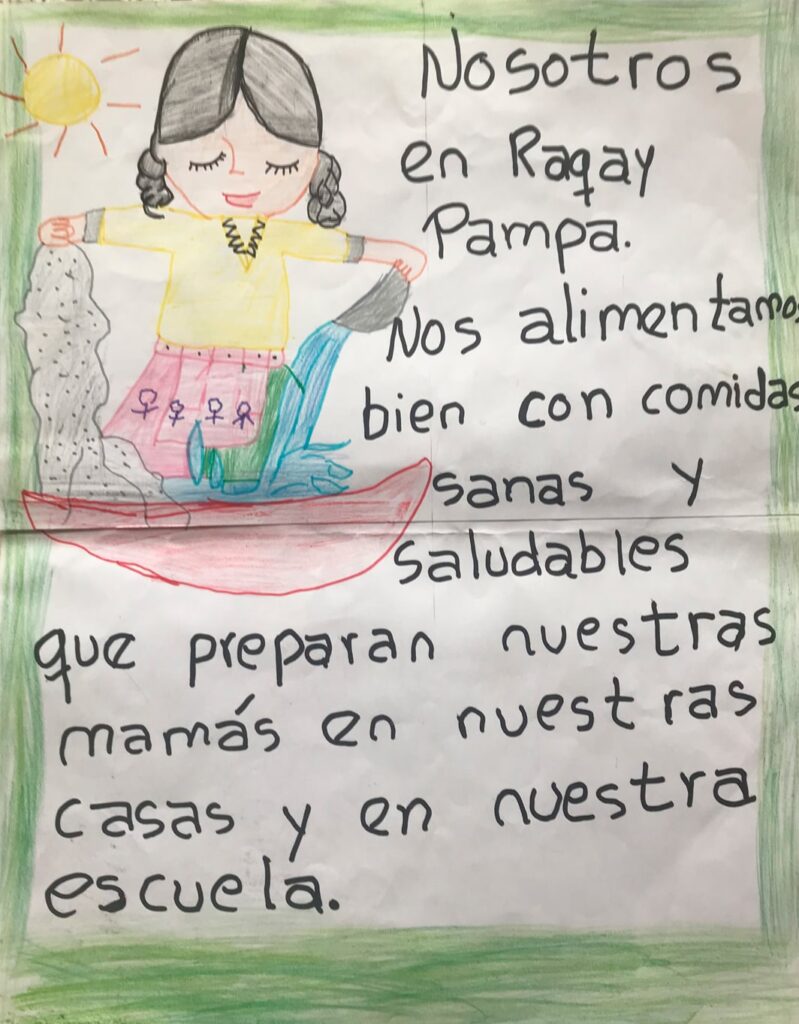

Wearing the traditional clothing that distinguishes the Quechua people of Raqaypampa from everyone else, Anayra came to the village school, where she is in sixth grade, to show the drawings that some students made illustrating their culture, their village, and their eating habits. The two drawings she holds depict two people from Raqaypampa in traditional dress: a woman in clothing similar to her own and a man wearing black and white sandals, wide gray woolen trousers with horizontal embroidery, a white shirt, a vest with embroidered sequins, a woven belt adorned with colorful tassels, and a white hat similar to the women's.

The faithfulness of the drawings to the traditional clothing speaks to the pride with which the people of Raqaypampa present themselves and represent their culture. “This has been our traditional clothing for a long time, and it has great significance,” Anayra tells me in Quechua, her native language, before adding, “Our culture must be preserved.” What she says isn't the result of any rehearsal; it's the voice of conscience regarding the value of her identity. “I wear our traditional clothing when our teachers ask me to; I also usually wear it to festivals and when we have to go to events,” she explains, referring to visits they make to other places where the people of Raqaypampa display themselves in all their splendor.

Anayra has had time to dress up to show off to the visitor because her house is near the school, about a ten-minute walk away. “I live down the hill, near the market,” she explains, referring to the town's main square, which on Thursdays, like today, hosts a street market selling everything from food to music DVDs, coca leaves, and sportswear. “On Thursdays, we buy what we need to cook,” she adds.

From her home to school, she travels back and forth from Monday to Friday for classes. She leaves at 8:30 am and returns after 1:00 pm. Before going to school, she eats a hearty and very typical Quechua dish at home: lawa, made with wheat or corn. Lawa is a thick Andean soup prepared with wheat flour, corn, or another ground product, along with potatoes, vegetables, and meat.

Photo: Santiago Espinoza.

At school, Anayra and her classmates have two breaks, one of 10 minutes at 10:05 am and another of 30 minutes at 11:35 am. The latter is longer because it is used to serve school breakfast, a complementary feeding system offered by public educational establishments in Bolivia to guarantee better nutrition for students.

In Raqaypampa, the provision of school breakfasts is managed by its Indigenous Peasant Government (GAIOC), a pioneering regime in Bolivia with political and administrative autonomy based on Indigenous culture. This system stipulates, among other procedures, that the community, gathered in assembly, defines the logistics of the supplementary food program for children, from defining the menu to how the meals are prepared.

A few minutes before the bell rings for the second recess at school, the mothers in charge of preparing the day's meal are gathered in the kitchen: lentils with potatoes and rice, to be divided into 186 portions, one for each student in the school. Only the smell of the food can compete with the impromptu soccer games and chases that the boys and girls engage in during their break. If they run, it's no longer after a ball or a classmate, but to get their still-steaming lentils with potatoes and rice.

Lentils and rice are products that arrive in the community from elsewhere, but potatoes are a staple food of the Raqaypampa people, who cultivate and harvest them across much of the 556 square kilometers that comprise their indigenous peasant territory. The tuber, along with wheat and corn, is one of the three main crops of Raqaypampa, which ranges in altitude from 1,670 to 3,450 meters above sea level. While potatoes and wheat are planted in the higher elevations, corn and some vegetables (broad beans, peas) are cultivated in the lower areas. These crops sustain their ancestral system of food sovereignty, which, although still in place, has been threatened in recent years by agricultural decline, climate change, parental neglect, and the influx of junk food.

Photo: Santiago Espinoza.

Eat what you grow

Anayra is the protagonist of this story, but she's not the only one. In the school room where the drawings are displayed, she's accompanied by Dayer Montenegro Albarracín, Rosmery Camacho Sandoval, and Juan David Cruz. Five of their teachers are watching over them to give them confidence and clarify things they understand better in Quechua than in Spanish, the two languages in which they receive instruction.

The youngest is Dayer, who is 7 years old and speaks timidly in Spanish. He has drawn his house and his mother cooking lawa de maíz, a dish he likes almost as much as the api (a typical Andean corn porridge) he receives some days at school. Nine-year-old Juan David also “loves” lawa. He said so himself, “I love it,” in Spanish he admits he doesn't speak fluently, although what he tells me is quite clear. In his drawing, a woman is preparing “t'anta” (bread in Quechua), accompanied by a text that reads: “In Raqaypampa, we eat healthy and wholesome food prepared by our mothers at home and at school.”

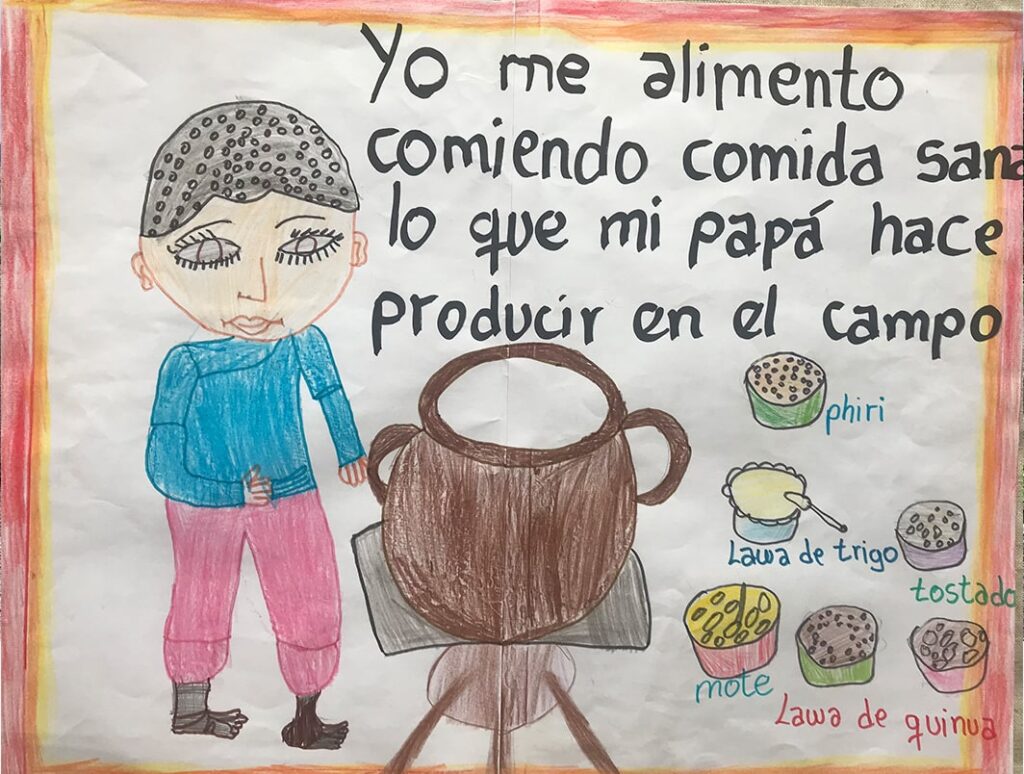

The drawing Rosmery, 10, is holding also includes a caption. “Good nutrition prevents many diseases. That’s why my mom cooks healthy meals,” it says. Next to it is a woman from Raqaypampa carrying a wawa (baby) on her back while peeling potatoes. An illustration that, Rosmery clarifies, mixing Quechua and Spanish, is not hers, but rather that of her friend Erlinda, who has asked her to present it. In another drawing, not by any of the four of them, but brought along for display, there is a child in front of a clay pot in the middle of cooking, and an explanatory caption that reads: “I eat healthy food, what my dad grows in the fields.” And then, some small plates are labeled with words: “phiri” (lightly ground wheat or quinoa, cooked and seasoned with vegetables), “wheat lawa,” “tostado” (toasted wheat grains, usually with added salt), “mote” (boiled corn kernels), and “quinoa lawa.”

These foods are a staple of the traditional diet of the people of Raqaypampa, largely because they grow their own ingredients on their land. However, the residents acknowledge that in recent years agricultural self-sufficiency has begun to decline as a result of droughts and other events associated with climate change.

The lack of water sources is the most critical problem facing Raqaypampa. Raúl Rodríguez, executive secretary of the Central Regional Union of Indigenous Peasants of Raqaypampa, the most representative social organization in the Raqaypampa territory, which brings together five peasant sub-unions and 43 agrarian unions, states this unequivocally. He recalls that in 2021, “there wasn’t even enough water to drink.” They didn’t even have any in their lagoons, so people had gotten used to buying water. “It was terrible. Then it rained suddenly (a lot) and ruined the crops. That’s why there aren’t many potatoes now. It rained for almost 15 days straight, and then there were hailstorms. There’s no life left for the farmers,” he laments.

Raúl explains that to guarantee production for their own consumption, they rely on their grain storage system, which allows them to save wheat and corn from past seasons. However, the same cannot be said for potatoes, which cannot be stored for long periods. “Potato, wheat, and corn production has completely changed. Before, we had tons of potatoes and wheat. We had hectares of fields. Now, not so much anymore, just a little. If before we harvested up to 40, 50, 70 quintals of wheat, now we only get a maximum of 10 quintals,” he illustrates.

Water provision is the task on which the Indigenous Autonomous Government of Raqaypampa has been working most diligently. Its highest administrative authority, Florencio Alarcón, says they already have one dam, a second one nearing completion, and a third one under construction. However, Florencio acknowledges that these dams are still insufficient to supply the more than 7,300 people who live in the territory, according to data from the indigenous government. Even the small family reservoirs do not meet the total demand for water for consumption and irrigation, although they do help to preserve crops.

Agriculture is also declining in the region because it is no longer profitable for the people of Raqaypampa. “People aren’t farming as much anymore because they’re not making a profit. A sack of corn (57 kilos) costs between 120 and 130 bolivianos (17 to 18 dollars), and that’s not enough. Wheat isn’t going up either. Farmers do the math, and if they can’t make a profit, they don’t farm,” Raúl explains. And he speaks from experience. Although he is still a farmer and cultivates his land, he uses his harvest exclusively for his family’s consumption. His income comes from something else: he owns a small construction business.

Agriculture is no longer the most decisive economic activity in Raqaypampa. Others, such as commerce (selling household products), transportation (there are associations of drivers for local and interprovincial trips by car and motorcycle), construction, and mining (there is a cooperative for antimony mining), compete with or complement it. This applies to those who still remain in the indigenous territory, as since the 1990s many have migrated to other regions of the country (Cochabamba and Santa Cruz) and even abroad. Florencio estimates that in the 1990s the population of Raqaypampa was around 12,000, while now it is below 8,000. According to his 1999 Indigenous Plan, its approximate population was 11,800 inhabitants, while by 2021, it had reached 7,344, according to data from the indigenous government. Those who migrated left in search of work and better living conditions.

Photo: Carlos Espinoza.

More lunch than breakfast

The scarcity of water for irrigation and the poor profitability of cultivated crops explain the decline of agriculture in Raqaypampa. This decline is attributed, among other factors, to a fact that alarmed the indigenous government in 2019: children between the ages of 5 and 12 showed signs of malnutrition. According to Florencio, the study that raised this alarm was commissioned to researchers from the Universidad Mayor de San Simón (UMSS).

The UMSS School of Medicine, through its Biomedical Research Institute (Iibismed), conducted a diagnostic study on a population of 1,137 children to detect the presence of parasitic infections (anemia, based on their experiences), according to the document “Systematization of the Public Management Experience of the GAIOC TR,” from July 2020, prepared by Juan Sánchez Gonzales. The nutritional status examination found that 72.1% (820 children) had a normal diagnosis; 24.6% (280 children) had second-degree malnutrition; and 3.3% (37 children) had third-degree malnutrition. “These results were obtained based on the stool and blood samples, as well as the height and weight measurements taken from each student,” the document adds.

The food problems in Raqaypampa are consistent with studies on the scope and challenges of indigenous autonomous governments in Bolivia. This is the case in the final report of the “Project for Strengthening the Plurinational Autonomous State and Intercultural Democracy ,” implemented by the United Nations Development Programme, which recommends that authorities “include more comprehensive perspectives” that “recover/activate cultural knowledge and wisdom and that integrate economic and productive proposals, food security, health (including so-called 'natural or traditional medicine'), education, environmental and natural resource management, risk management, and climate change, among others.”

Faced with alarming malnutrition, the indigenous administration of Raqaypampa expedited efforts to combat it. One of these was adjusting the school breakfast menu, which, in practice, became a lunch program. The provision system was implemented collaboratively: while the authorities would ensure the supply of dry goods (such as charque or dried/dehydrated meat and lentils), parents would contribute fresher ingredients (onions, tomatoes, potatoes), and mothers would be responsible for cooking. Some of the dishes served as a combined school breakfast and lunch program since then include api with buñuelos (fried dough), rice pudding, peanut soup, and lentils with rice.

According to Florencio, the implementation of the new school menu has had a positive impact on the nutrition of the children. However, it may not be enough, especially during the hours the children spend at home. Clemente Salazar, a former leader and educator from Raqaypampa, believes that the adults in the town tend to "neglect" them. He finds the word harsh, but justifies it: "They go to school alone, come back home, sometimes they do their homework, sometimes they don't. There's neglect." Their parents and the adults in their care spend a lot of time away from home for work.

This isn't the case for all families, but in those where it occurs, the "neglect" extends to their food as well. "Because, with the children alone, we don't know what they eat, what they prepare for themselves. Sometimes, in town, they make fries with sausages, fried chicken, that's all they go for. What they call junk food," says Clemente. The boys and girls at the school don't admit to eating junk food, but their teachers explain that such dishes are readily available on market days, when there's more commercial activity in town.

Clemente believes that the "abandonment" of children he alluded to earlier means they are becoming increasingly detached from agricultural work. Their time is taken up by school and homework, but also by technology, especially the cell phones they now have access to. "Children are isolating themselves from home, and people are noticing," Clemente says resignedly.

And because they are realizing this, the people of Raqaypampa are considering adjusting their children's education system so that it is organized around a regional calendar and a diversified curriculum. The idea is to return to a model consistent with the productive and cultural life of Raqaypampa , like the one Clemente and other former leaders promoted some years ago in the territory, but which has been displaced by the regular calendar imposed by the Bolivian education system. "We want to return to that system to improve educational performance, but also to incorporate them into cultural activities, such as planting and harvesting," he explains. In their view, fieldwork, planting, and harvesting are not just agricultural activities; they are ways of practicing their culture, of embracing their Raqaypampa identity.

Along these lines is another project by the indigenous government to improve food security: the creation of family gardens. Florencio explains that the initiative is already bearing fruit, allowing many families to grow vegetables (peas, broad beans), tubers (carrots), greens (onions), and fruits (tomatoes), which complement their more traditional crops (potatoes, corn, wheat) and are beneficial to their nutrition.

Photo: Carlos Espinoza.

The road ahead

Anayra is ready to leave. She and her three classmates have more than fulfilled their teachers' assignment: to describe, through drawings and words, their Raqaypampa identity and the eating habits of their culture. There are still a few minutes left before the dismissal bell frees them from school.

When she gets home, Anayra says she'll heat up the morning's food to satisfy her afternoon hunger. Rosmery, her friend, is waiting to get home to make "phiri," something she already knows how to prepare: "We have to grind the wheat, then soak it, and then 'lawar' (put it in the pot to cook)." Whatever she cooks will also be for her brother.

The task is even harder for another of her classmates. One of the teachers at the school tells me about her. The girl is eight years old, motherless, and lives more than an hour's walk from the school. She isn't here right now. She's probably hurried to try to get home by 2:00 p.m., the time she expects to be back. She expects, because neither she, nor her father, nor her brother own a watch. They get their bearings from the radio they turn on every morning, before 6:00 a.m., so they can cook lawa or mote, eat before leaving, walk for one or two hours, and get to class on time. She makes the trip every day, there and back, sometimes alone, sometimes with a friend who lives a little further up the road. And the journey only ends when, once home, she helps her father with the potato harvest. While he digs, she gathers the potatoes in a basket and carries them to the "phina" (where the tubers are piled up). It's not just any job. It's the job that puts food on her table, but also the one that makes her a true Pampas woman.

Photo: composition by Giovanni Salazar of Agenda Propia.

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.