How Ballroom culture was born: an LGBTI+ political celebration

Ballroom dancing, which is all the rage in Argentina, Mexico and some South American countries, has a long history of struggle.

Share

GUADALAJARA, Mexico. “I have the right to show my color, darling! I am beautiful and I know I am beautiful!” These were the words that Crystal LaBeija, a Black trans woman and drag queen, uttered in 1967 to denounce racism in the drag queen beauty pageants of the time.

That “iconic” scene was recorded in the documentary The Queen and would mark the starting point of ballroom culture and voguing, a political action that puts LGBTI+ dissidences and identities at the center to celebrate their existence.

What is the political value of ballroom culture? What happens at a ball? What is the power of vogue? What's the deal with chosen houses and families? What is kiki?

To answer these questions and learn the basics of ballroom culture, Presentes spoke with people who are part of this culture in Mexico, Peru, and Argentina.

The most important moments in ballroom culture

The first dance

“After that iconic scene, Crystal and her friend Lottie (another drag queen) created the first ball exclusively for Black and Latinx people. Thus, ballroom culture was born, an underground culture of Black, Latinx, and sexual and gender dissidents with the intention of celebrating themselves and the need to generate support networks in a world that tells you that you cannot exist,” narrates Furia 007 , alter ego of Emilio Ramírez, an architect and dancer who was part of House of Apocalipstick and House of LaBeija, in an interview.

In ballroom culture, people who, while not integrated into a "house", are a vital part of this culture by organizing balls, sharing knowledge, etc., are known as 007s.

The first ball organized by Crystal and Lottie LaBeija took place in Harlem, New York in 1972 and marked a milestone, following the Stonewall riots (1969), for Black and Latino LGBTI+ people to come together not only to dance or cross-dress but to celebrate their identities in a context of exclusion, discrimination and violence.

That ball was announced as follows: “ Crystal and Lottie LaBeija present the first annual House of LaBeija ball .” Writer Michael Cunningham recounts in his article “The Slap of Love” that this was the first time the term “house” was used. It's a concept within ballroom culture that refers not only to a group of LGBTQ+ people who team up, dance, and compete in different categories at balls, but also serves as a community space and a chosen family.

Heirs

Fiordi Vemanei (social worker, queer, non-binary brown person and founder of House of Glorieta , one of the first houses in Argentina) finds the political value of ballroom culture in the opportunities it provides to work in community and celebrate dissidence.

“Those of us within the ballroom culture are heirs to that Crystal LaBeija who rebelled. We inherited the power to organize ourselves against the heterocispatriarchal system and the bodily hegemony that has been judging us. And I always say it: if there is a ballroom culture, it's because there is a system that continues to exclude us. That doesn't mean it's a culture of symptomatic behavior, but it is a response to the culture that allows it. And dance, especially voguing, is the method of protest we found to say that the equality they establish as a given with us is not being upheld. But it's also the legacy to show ourselves, to celebrate ourselves, to be queer in peace, among peers, as a family.”

Thus, after the first ball, the term home and the chosen family take on significant value for those who live and build this culture.

“We stretch, we twist the idea of family”

Historically, LGBTI+ people have been expelled from their families during childhood and adolescence, which consequently brings chains of exclusion that limit access to their most basic rights such as education, health, housing, and work.

In this sense, the house system has played an important role, since the birth of ballroom culture, in creating support and knowledge networks, and building activist and community alliances to respond to the urgent needs of dissident and LGBTI+ people.

“Ballroom dancing tells this system of exclusion — look, we’re here, we’re dancing, resisting, we’re putting in the effort, the time, and to top it all off, we’re family. We’re taking on the central group that this system loves: the family. Well, we’re family too, we stretch, we twist the idea of family. I’m a mother, but I’m also a queer person; there’s an escape there and a form of resistance,” explains Fiordi Vemanei .

Mother, the guide

In the origins of ballroom culture, houses were made up of mothers, fathers, and children, a structure that remains to this day. There, the roles of mother, father, or head of house are not associated with the gender assigned at birth, but rather with the provision of care.

Laurent Tropikalia, mother and founder of House of Tropikalia ; one of the first houses in Argentina, tells Presentes that the figure of mother is related to being a guide.

“I started out as my daughters’ vogue mother because I was their teacher, showing them the style (of dance). But I was also responsible for educating them with everything I was researching and learning about the culture. This role is mostly about being a guide, a mediator, a listener. It’s about creating bonds based on empathy, a superpower that comes with solidarity, to make the struggles visible and also identify our own privileges. You need to train your body to grow; and with love as a constant process that makes you work on your relationships. This is my experience. I don’t know if all mothers react the same way; maybe some are more inclined towards superiority, being like a duchess, which is something more pronounced in the mainstream.”

"Don't romanticize ballroom dancing"

Fiordi warns about the importance of "not romanticizing or idealizing ballroom culture."

“Ballroom dancing is also permeated by power dynamics. Ballroom culture isn't a panacea for equality; things happen there, just like in any other cultural space. And that's where we need to focus on not falling into the patriarchal idea of family where one head decides while everyone else obeys. It's something we have to resist because patriarchal culture affects us all, and we come with an internalized representation of family. Reinterpreting that is a challenge for everyone.”

“Show off, daughter, pose, pose! You are the center of this fantasy!”

“At a ball, the people walking around take center stage, and with them, their identities. It’s the moment when everyone is waiting to see you. Show off, girl, pose, pose! You are the center of this fantasy, you can be whatever you want to be, and at this moment, you are the role model for everyone else,” emphasizes Julius Prince , father and founder of Kiki House of Prince , the first house in the ballroom scene of Lima, Peru.

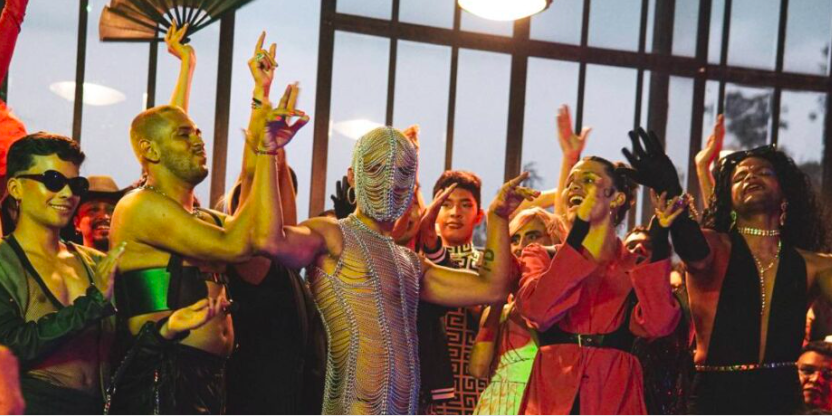

Ballroom culture isn't just about families and community building. It also features events called balls, organized by houses, where battles in different categories take place, showcasing diverse identities, gender expressions, and body types. Participants compete to demonstrate their dance and performance skills on the dance floor, in front of a panel of judges, an MC, chanters, and an audience.

“A ball is, in short, an LGBT party. It’s even a unique event. No two balls are alike; it transcends simply because LGBT people come together; and it transcends even after it ends because you take away unique experiences: whether you need to practice to improve, whether something was reported; whether you won or lost, whether you were the best that night,” emphasizes Bryan Cárdenas, better known as Zebra Drag, founder and leader of House of Drag , one of the first drag houses in Mexico, in an interview.

The roles

In addition to those who make up the houses, those who walk the categories, and the community that attends, there are three essential roles for a ball to happen.

• MC or Master of Ceremonies: This person keeps the show going, energizes the audience, and introduces the judges, the categories, and the contestants.

• Chanters: These are the people responsible for performing chants, vocal rhymes that accompany the competitors.

• The judges: This group is usually made up of people who have been in the scene for a long time, are pioneers, or are veterans; they know the criteria for each category. They award "tens" to those who advance in the categories, and if they give you a "chop," it's a way of saying, "Thanks for trying, but you're out."

Once the battle is over, it's common for the participants to hug each other in a gesture of recognition for their effort and their place in the ball. Fiordi adds that this is something that "shouldn't be forgotten."

The categories

“Enjoy the categories, but also enjoy embracing the other person, the one who fought and gave it their all. Who pushed you to the point where you say —oh, she’s going to beat me. And I adore you, I adore you for pushing me to that limit. It’s something we shouldn’t forget because we all come from the same place or at least we all went through this shitty system at some point.”

The categories being battled have their own language and techniques, and during the ball, they are accompanied by different types of house music beats. In addition, it's common for the audience to wave their wrists, snap their fingers, and shout at the top of their lungs the names of the wrestlers and the houses they belong to.

- Face or face, each participant shows and highlights their beauty.

- Runway or catwalk, where the key is in the walking, some subcategories are: American and European.

- Fashion or style, where outfits are rated.

- Sex siren, a category that seeks to celebrate sensuality and seduction.

- Voguing, an urban dance created by black and Latin dissidents, from which three styles emerge: old way, vogue femme and new wave.

The categories, says Furia 007, “are not limiting or defining; they have emerged and evolved as dissident identities name themselves, take to the dance floor, and demand a place. They have also evolved in a kind of syncretism with other cultures, techniques, and urban dances like vogue femme, which emerged in the nineties and is now one of the most anticipated categories because it brings the famous five elements of vogue to the dance floor.”

“You are not just dancing a dance, you are dancing history.”

There is no official history of how and where voguing originated, but two are commonly recounted: One is that as an act of self-defense, trans women and gay men deprived of their freedom posed against those who sought to violate them in Rikers Island jail.

The other story says that, in 1979, on a night out at a club, drag queen Paris Dupree took a copy of Vogue and, to the rhythm of house music beats, imitated the poses of those models as an act of throwing shade or doing shade .

In ballroom culture, shade is a verbal and gestural language battle to subtly and perceptively insult someone else, but it has also been "an alternative form of care."

This is explained in an article by Michael Roberson, an activist who works in HIV prevention through voguing.

“Black and Latinx trans and queer people constantly face verbal and physical aggression based on who they are, how they act, how they dress, how their voice sounds, how smooth or rough their skin is, etc. The practice of reading and shadowing is not purely malicious, but is based on the need for survival of oneself, our friendships, and the community.”

Vogue Femme

Today, vogue femme is one of the most celebrated categories within ballroom culture. Not only because it's a dance style that requires physical fitness, coordination, and body expression, but also because it's a technique that tells stories. It celebrates the existence of dissident identities and diverse bodies, and because it centers the power of femininity.

“The raw material of voguing is being posh, and it has been a very important form of feminine expression for LGBT people. It’s our way of saying, ‘Your heteropatriarchal system isn’t going to fuck me up.’ It requires incredible strength, control, and physical power. Furthermore, accepting these feminine gestures in my body opened up a tremendous memory, not only psychological but also physical. It changed my life, and more than the possibility of being gay, it’s about giving myself the right to be gay,” Furia 007.

“You’re not just dancing a dance, you’re dancing history, and you feel that strongly. It’s like a shamanic journey, I’d say, it’s very difficult to explain. But you know that, as you dance, you’re also invoking those who resisted and succeeded,” says Fiordi Vemanei.

License to heal

“Ballroom culture gives you license to heal, to love your body, to love your femininity. It tells you—I am valuable, I am here, I have the right to live the way I am. And for those of us who grew up in the 80s and 90s, in a very conservative Peru, being yourself was really tough. It was about living it alone, and if you found ways to do it communally, you did it underground. That's why ballroom and vogue have given me the right to be proud of who I am and to celebrate it,” Julius Prince.

“I think from the outside a vogue battle looks like an energy of sorts: they’re beating each other up, or it’s a beautiful fantasy. And it is a beautiful fantasy where we are constantly expressing ourselves, between empowering who we are and dancing for what we don’t want. Inside it’s a joy, and outside I’d scratch your face because I can’t stand your machismo. I don’t like your heterocispatriarchy and all that shit,” Laurent Tropikalia.

“Society has imposed how one has to be a man. You can’t bend, you can’t move your hips, you can’t put your hand behind your back. Doing it is more than an act of provocation; it’s a protest. Doing it in hostile environments like the street or your own home becomes an act of resistance. I love being feminine, and I love being queer,” Zebra Drag.

“Ballroom and HIV”

“Kiki speaks to the mainstream to say: don’t get lost in the battles, remember where we come from, why we are here. Why we are resisting,” Fiordi Vemanei emphasizes.

In the 1990s, ballroom culture celebrated its 30th anniversary. Its sense of community, activism, and care remained and grew even stronger as the HIV pandemic claimed the lives of members of this culture.

In the early 1990s, House of Latex was founded, a house sponsored by Gay Men's Health Crisis, New York's largest HIV care organization. This partnership was established with the intention of working on HIV prevention and education for people both within and outside the ballroom culture.

doctoral thesis, philosopher Edgar Rivera explains that this alliance led to LGBT+ minors being integrated into the house without undergoing tests that demonstrated their voguing skills or other categories.

The House of Latex agreements

To be part of it, you simply had to fulfill three agreements: attend regular meetings, walk in balls representing the house, and prepare yourself as peer HIV prevention specialists.

Following this, a phenomenon emerged in which the "legitimacy" of the houses and their selection processes began to be questioned. This led to the birth of the Kiki scene in 2003.

“Kiki is understood as the more activist side of ballroom culture and as the birth of local scenes whose objective is to open up the ballroom competition space to minors. It also involves the creation of permanent actions in response to HIV and STIs, access to health, and community actions on human rights. But with kiki we also refer to the nascent, local scene,” explains Laurent Tropikali .

The road to Latin America

Vogue arrived in Mexico through Mexican dancers from the urban dance scene who learned to vogue in the United States. One of them was Any Funk, a professional dancer and founder of House of Machos , one of the pioneering houses of the Mexican scene.

“By 2012, Any Funk was already showcasing voguing in urban dance studios in Mexico City, and several important figures in the Mexican scene, such as Annia Cabañas and Zebra D, were trained there. The contribution to building the scene from a more political perspective came from Omar Feliciano, a performance artist and activist better known as Franka Polari. In 2015, he organized the first public runway and voguing practices at La Puri (an LGBT club), and that same year the first ball in Mexico was held,” explains Furia 007.

Ballroom culture in Mexico began to stir thanks to this alliance between professional dancers, drag queens, and activists. And while this culture was growing exponentially, Franka Polari, founder of House of Apocalipstick , was promoting ballroom culture in various parts of Latin America.

In 2019, Franka Polari was in Buenos Aires, and Laurent Tropikalia was feeling uncertain. “I need to know if I’m ready to create my own home, that’s what I asked Franka; and with such love she told me, ‘I’m here to support you and encourage you in whatever you want to do. Whatever you decide is a starting point for bringing to your body what bothers your family and making those urgent needs visible,’” Laurent recalls.

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.