LGBT+ stories from the margins of Latin America

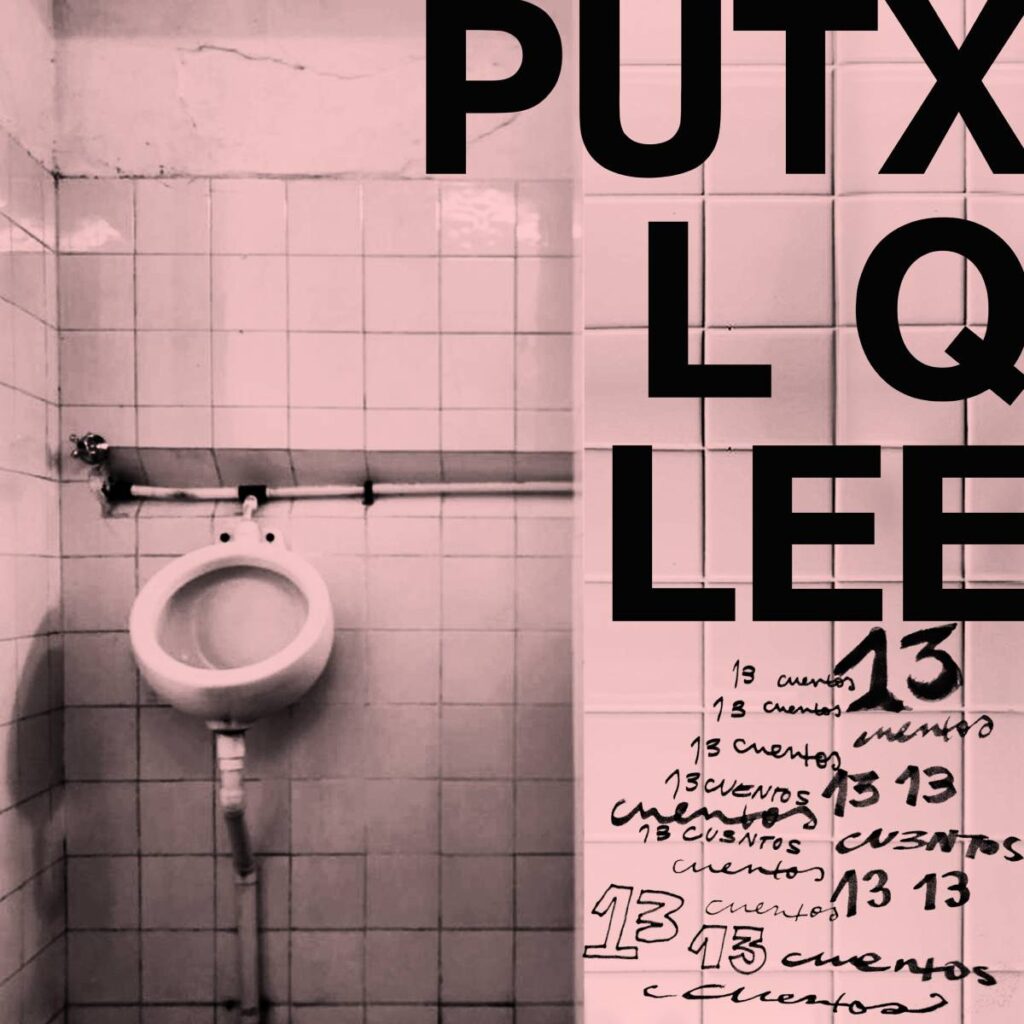

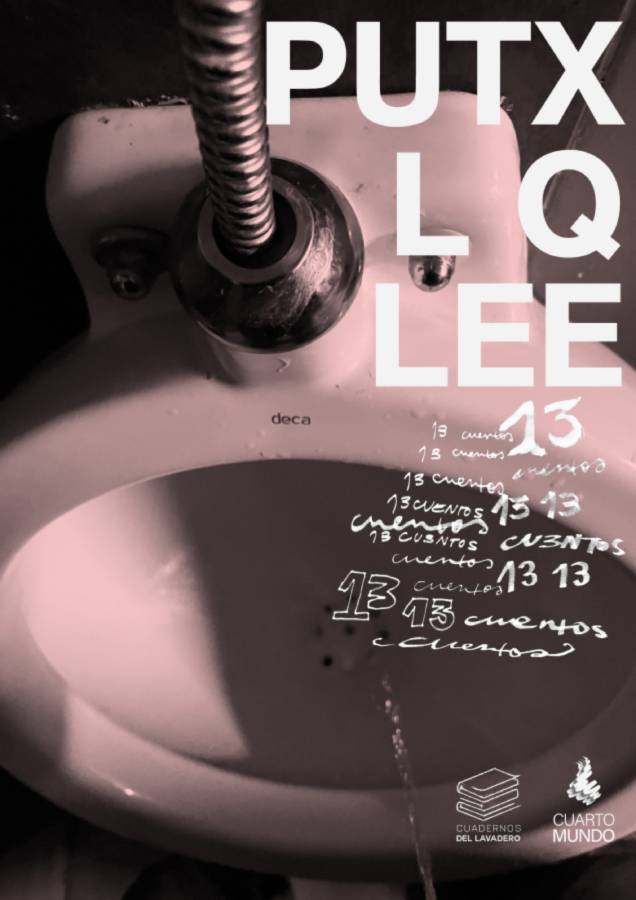

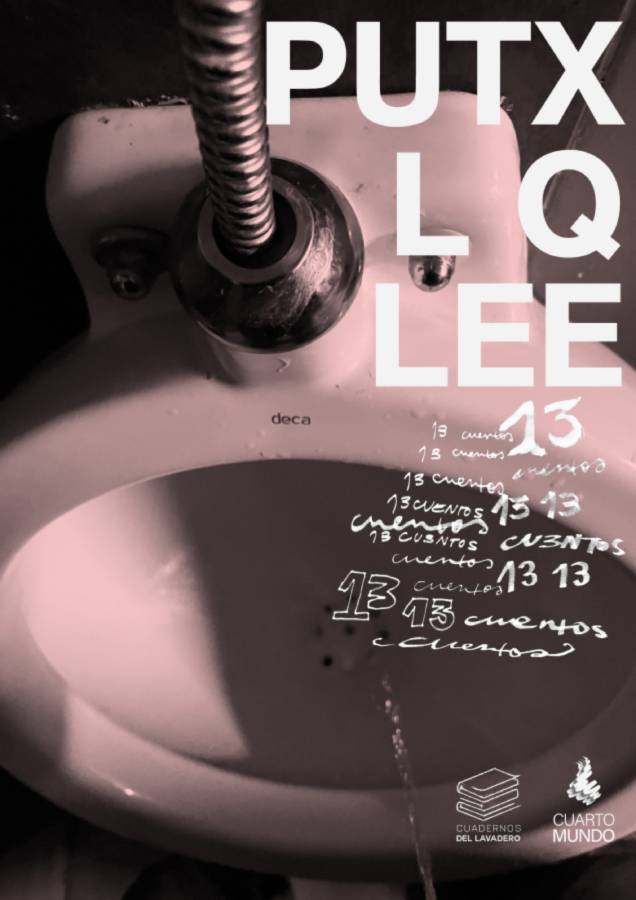

The collective Cuarto Mundo and Cuadernos del Lavadero launch "Putx lq lee", a book of thirteen stories where stories of exile, passions and violence are reconstructed.

Share

ASUNCIÓN, Paraguay. “The text is on the edge, with little margin, or right on the margin, just like our lives,” says poet Edu Barreto, one of the writers published in the book Putx lq lee (Faggot Who Reads). The notebook/bathroom/exile is the result of a call for short stories launched by the Cuarto Mundo collective , the producers of the podcast Puto el que lee ( ), Omar Beretta and Niqo Martínez, and the publishing project of designer Paolo Herrera, Cuadernos del lavadero (Laundry Notebooks).

The pandemic was like a party where the lights suddenly went out. “Imagine, one day I was dancing at the Mandril theater at a Sudor Marika , all of us topless, kissing and drinking coke with Fernet, and the next day they tell you two meters of distance, face masks, and you almost have to wear a helmet to go out on the street. That was a huge blow for all forms of dissent because the streets, public spaces, bathrooms, and nightclubs have historically been our stronghold,” Omar tells Presentes .

The Cuarto Mundo , a platform that produces and disseminates content about expressions of non-heteroconformist South American identity, celebrated its first anniversary in the midst of mandatory lockdown and, like many self-managed spaces, had to rethink itself.

To build a corpus

Paolo approached Puto el que lee and proposed that, together with Ediciones del Lavadero, they work on a collective project. Putx lq lee seeks to reflect the fusion between literature and sexual diversity through stories produced during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Most of the stories were written by different people from the sexual and gender diversity community; some are established authors and others published for the first time.

Participating in this edition were: Elian Cabrera, Fabián Alvarez, Arture Davila, Ferny Kosiak, Belén Rofrano, Analia Bustamante, Frank García, Sebastián Figueroa, Patricia Requiz Castro, Eduardo Barreto, Lucas Alcázar, Clara Ferguson and Luis Francisco Palomino.

When confinement led to encounters with mirrors, or, as one of the stories is titled, when eyes sprouted from the walls, the bathroom appeared as an oasis amidst homophobia. Omar felt he recovered the metaphysical sensation of encounter when he received those texts like hail during the pandemic.

“The stories arrived full of regionalisms, from Lima, from Uruguay, from Central America, from Entre Ríos, from Paraguay, from Buenos Aires, from the past, from the present. It arrived at a time when we are fighting for neutral Spanish, when we do not recognize any authority in the Royal Spanish Academy , when we are reterritorializing and redefining what our language is,” she reflects.

Reading oneself

“How do you tune an orchestra that doesn’t share a score? It goes out of tune. And that’s what’s beautiful about this book,” Omar explains. While these texts weren’t intended to be woven into a collective tapestry, they emerged as a chorus of crackling acts of disobedience. In this first volume, four major points of contact appear: mental health, confinement, identity, and dictatorship.

“The alarm and madness of a new virus in the world is no small thing for LGBTIQ+ people who know about pandemics, who have been told that we are contagious, that we are a threat,” says Paolo.

They politicized the “pejorative” term “faggot” and placed the reader in the position of someone who reads themselves. But who also writes and narrates themselves. For this reason, the stories were submitted to the call not only as texts but also as audio recordings with the voices of the authors themselves.

The book contains stories from Paraguay, Argentina, Uruguay, Bolivia, Peru, and perhaps some other countries as well, but they don't remember because they didn't think only about territories or LGBTI stories.

The call was open to any theme and the selected participants were "voted" by the audience through their YouTube channel where they uploaded the narrated stories.

The selection and curation of the texts was carried out by Omar Beretta, Niqo Martínez, and Paolo Herrera. The proofreading and editing were done by the poet Fachu Aguilar.

Letters and illustrations

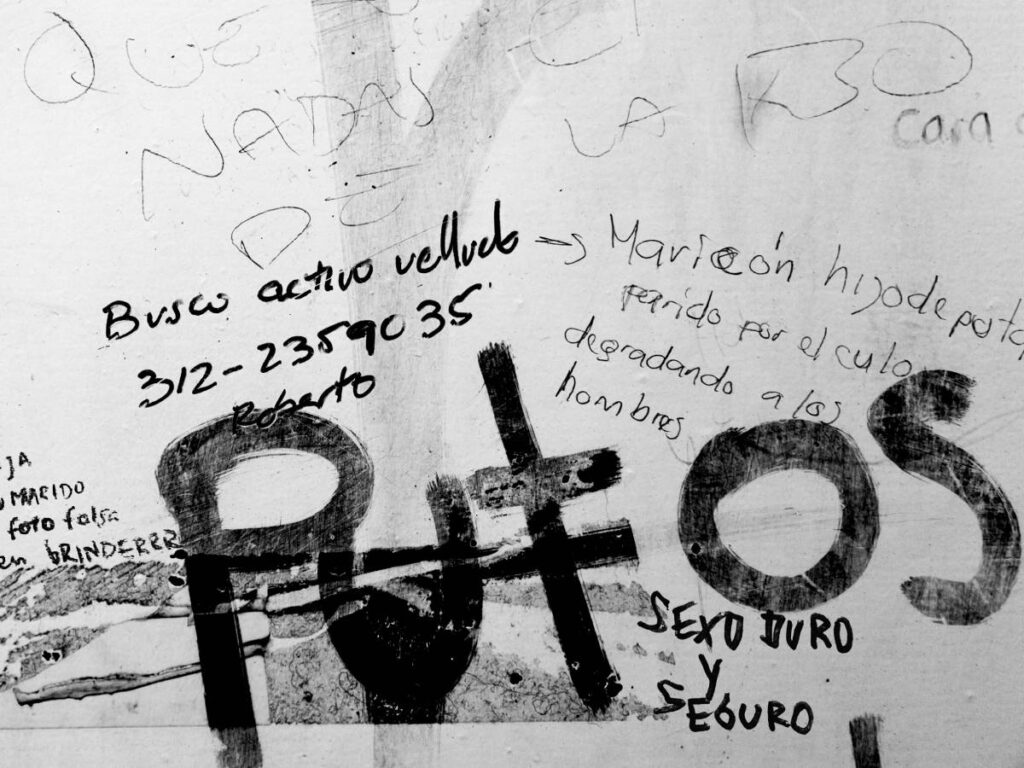

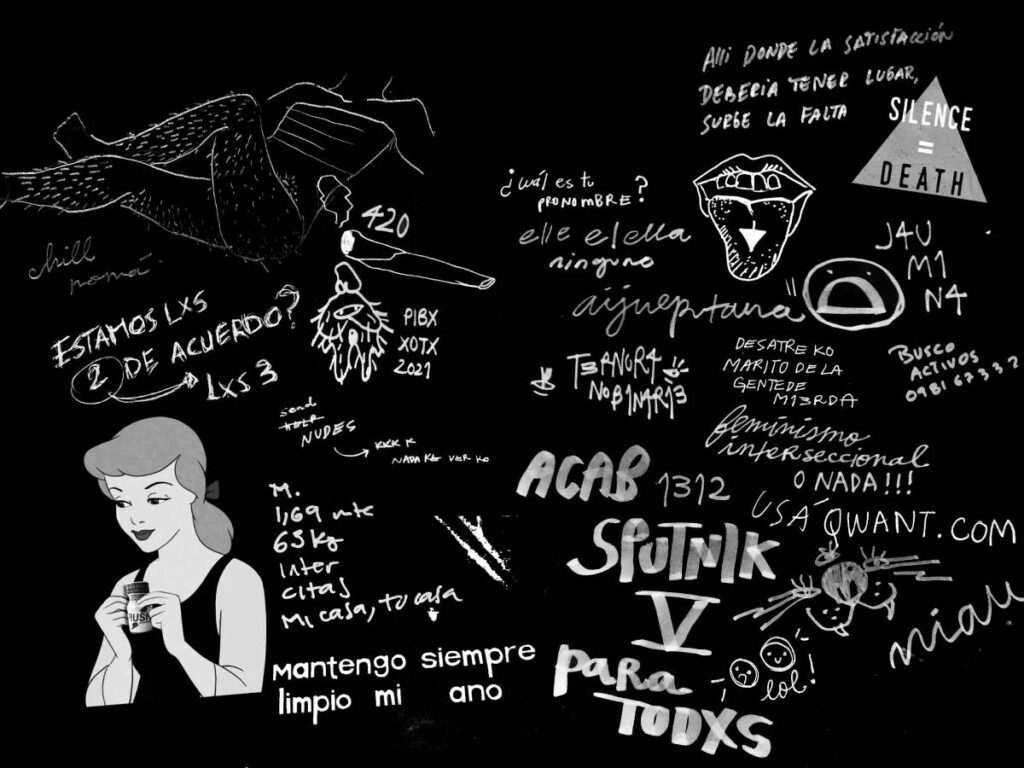

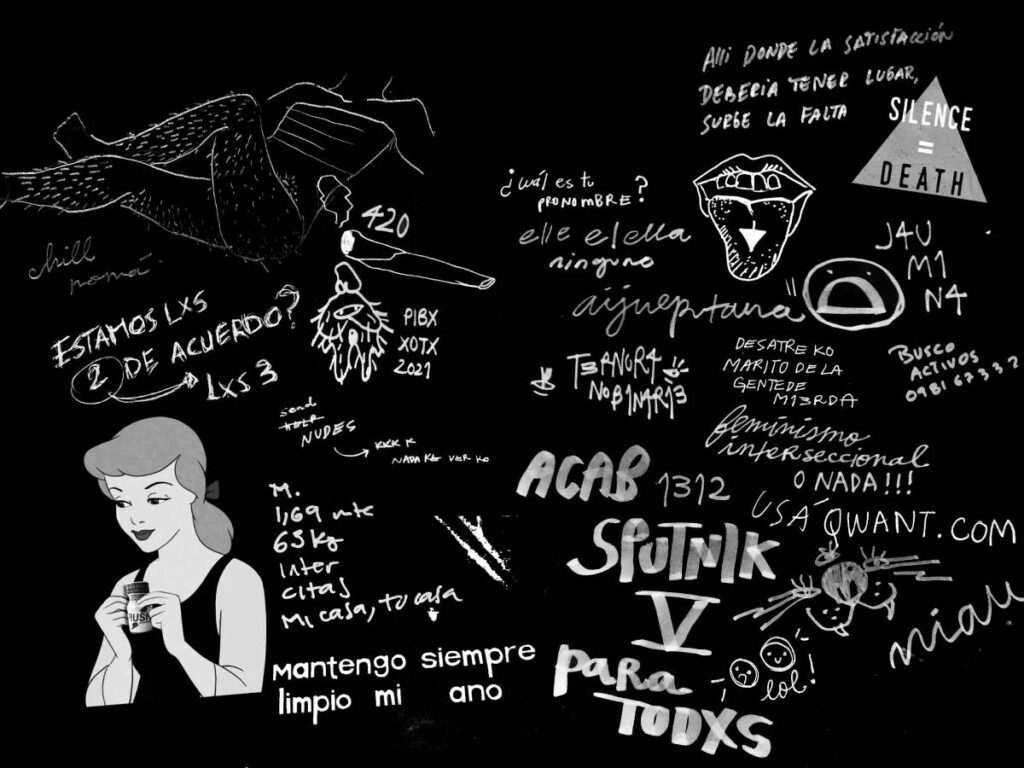

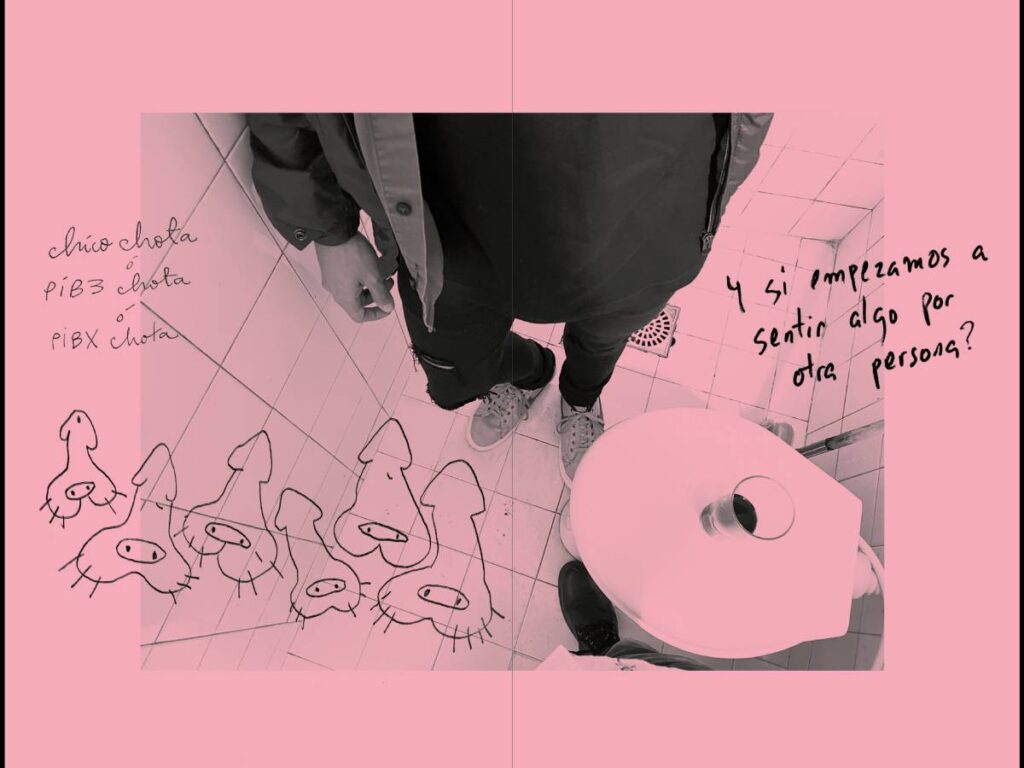

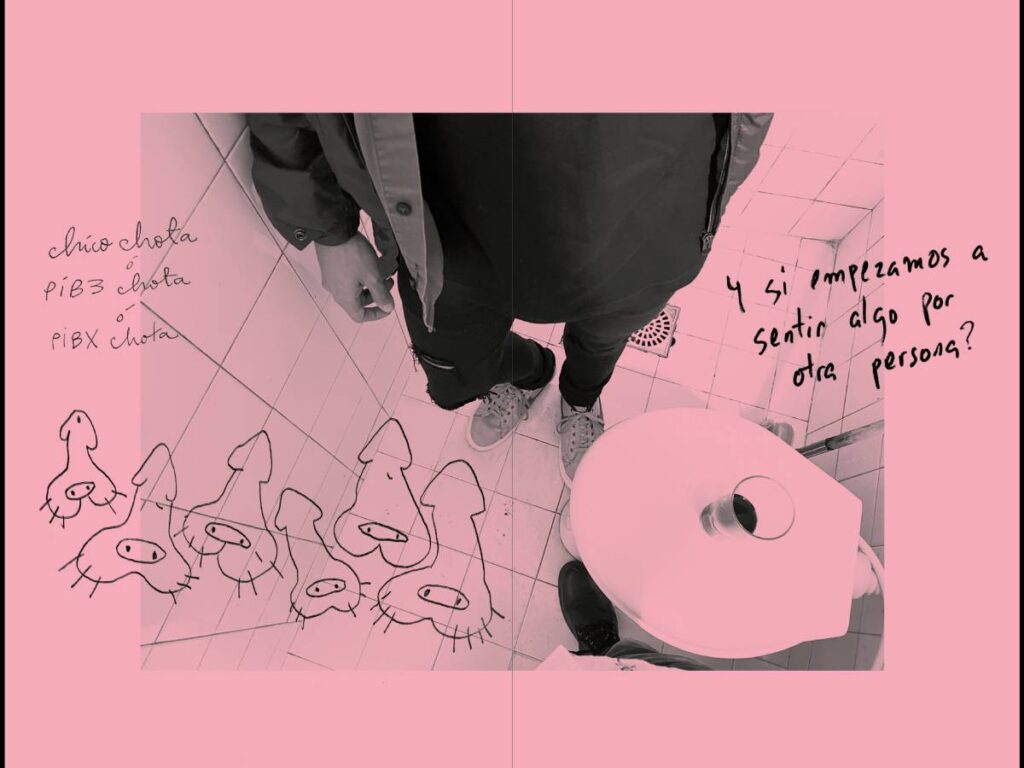

The visual narrative that accompanies the stories, through the graphic production of collages, drawings and photographs by the artist James Muriel, serves as a thread between the stories and the graphic conceptualization that comes together in the social treatment of the body.

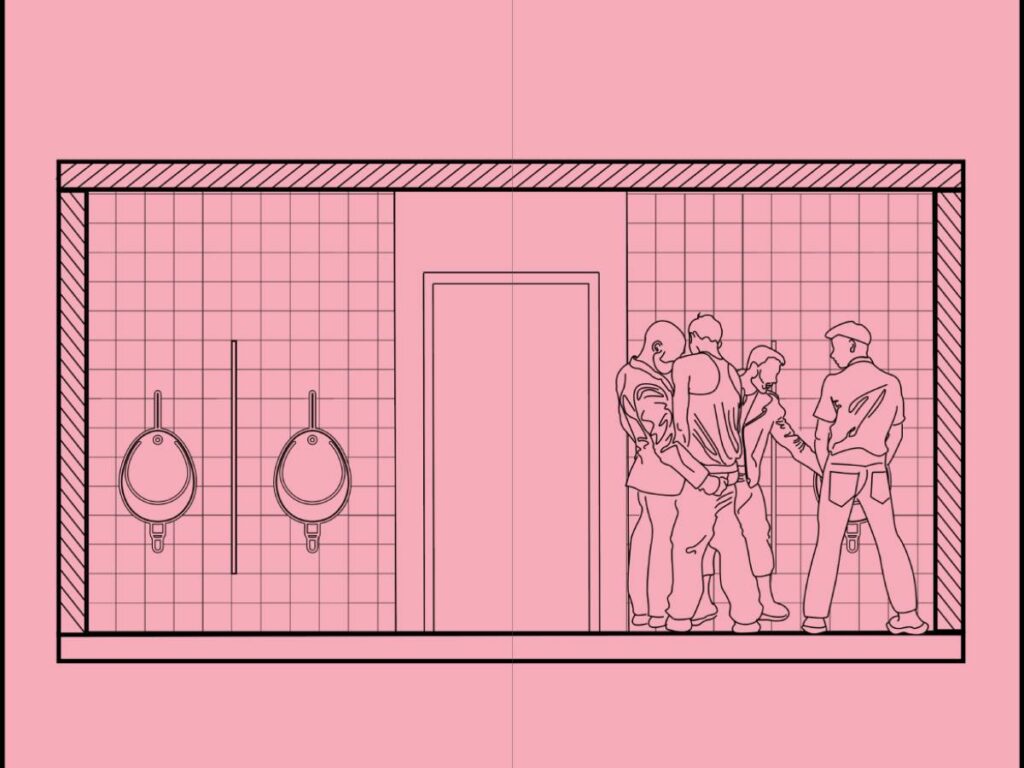

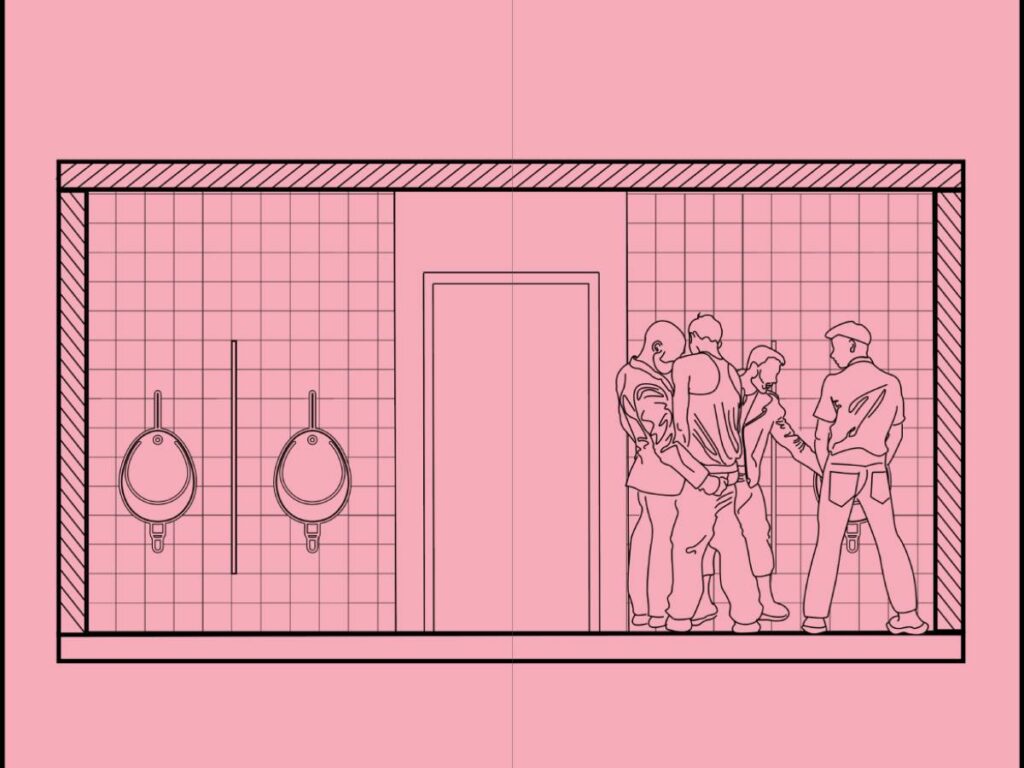

The representation of the bathroom as one of the most intimate areas of human life, but which, nevertheless, has been increasingly relegated to the background of social interaction.

“The process of creating the book was very fun and eclectic . Paolo and I would meet at his house in Saxony, reading and rereading the stories, trying to find a more symbolic way to approach them through images, but at the same time, creating a link between our imagery. For me, it was a meeting place that sought a less rigid, academic, and traditional way of presenting these stories ,” James explains.

“The necessary corrections stem from the inherent nature of disobeying the rules, the uses of language, and punctuation marks. We try to maintain that at all times and to intervene as little as possible in the original texts proposed by the authors. Clearly, there is a line that disobeys the precepts of the Royal Spanish Academy and uses language to construct imaginary worlds,” Fachu explains.

The bathroom, a place to break free from heteronormativity

When Omar learned to read, he found a phrase written above a urinal in a public restroom. "Whoever reads is a faggot," it said, and he thought, "Does reading this make someone a faggot, or are all people who read faggots?" "I thought reading was an inherent quality of being a faggot," he says, laughing.

That oracular bath one day revealed their destiny, and public baths became a meeting place for them too. In train stations, nightclubs, bars, cinemas, saunas, and memories of clandestinity or illegality echoed in the teapots during the dictatorships.

Public restrooms are a key reference point for sex within the gay community and have a history that stretches back centuries. The body is a sociocultural phenomenon with a history, embedded in a web of meaning and significance. It is symbolic matter, an object of representation, and a product of social imaginaries.

“The walls of public restrooms have always been, in my memory, places of intense political expression,” says Fachu Aguilar. “There, people express their ideas, where profanity abounds, where declarations of love converge with strong denunciations, where, every now and then, someone takes the liberty of drawing genitalia, writing odes to the body, disobeying certain rules, or even insulting the authorities.”

An internal trench

The Polish sociologist Norbert Elias defines the civilizing process as the stricter regulation of behavior, an increase in self-control, an expansion of the "limits of shame," and the exclusion of bodily needs from public life. Reclaiming the bathroom as a meeting place, a place for celebration, and also as the place where you go with your friends to share secrets.

“It’s the place in the club where you go to throw up, cry, or suck a dick. It means reclaiming that space that heterocapitalism wants as a dirty, closed, secluded, remote place, where we do things that aren’t public ,” Omar continues. The notebook is presented as a white, immaculate notebook, with no ink on the cover other than an embossed design in the shape of a urinal.

As one moves through the corridor-like pages, the walls become populated with signifiers. The visible and invisible walls in Putx lq lee capture the reader's gaze and place it in those "private" or "observational" spaces. The bathroom is the most intimate and is, perhaps for that very reason, a stronghold for LGBT people.

“Poetry is life itself, like going into a bathroom to urinate, defecate, or have sex. The bathroom is a threshold, as is expressing ourselves and surrendering to the poetry our bodies leave behind. Bodies that don't fit in, and that don't want to, then, in this world that doesn't,” explains Edu Barreto.

But, as James explains, the bathroom is also a space of vulnerability where people can experience discrimination. “They can be spaces we consider sacred or protective, and also spaces of danger. I think that increasingly we are not only taking to the streets, but also taking to the bathrooms through inclusivity.”

According to Niqo Martínez, the eroticization of these spaces doesn't necessarily originate in a child's mind, but rather is constructed from a prohibitive narrative. The trans community still faces an ongoing dispute regarding its identity within restrooms.

“The construction of the heterosexual subject, often by force, implies a certain level of willingness to erase a number of identity traits that we all know cannot be erased simply by preventing it from happening,” Niqo emphasizes.

She believes that this notion of rape in the bathroom or the bathroom as a necessarily erotic space is constructed from a conservative narrative, not precisely an LGBT narrative.

“We believe that in the construction of fiction there is a reappropriation. There is a construction of a link between the writer and that narrated space because, ultimately, we live in a world where we are not so aware, but in which everything revolves around fiction,” Niqo continues.

Memoirs 108 of the pandemic

“Thus, far away, the proclamation that we pray as our 108-night : For everyone, everything,” concludes the prologue of Putx lq lee.

“Since we can’t put our tongues in someone else’s language, at least these texts came together in a kind of orgiastic literary happiness that helped us get through the storm,” Omar reinforces.

The words "torta," "trava," "puto," and "marika" were once a prison, and then they weren't anymore. Reappropriation is the path chosen by diverse communities to love each other in the spaces where they were once confined.

The bathroom was the only place where they could exercise their freedom, especially during the dictatorship and the years that followed, when they risked their lives.

The book launch is scheduled for Friday, June 10th at 8 pm at La Serafina, a feminist cultural space (Asunción, Paraguay).

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.