They denounce serious human rights violations during the state of emergency in El Salvador

There is growing concern about the lack of information regarding those detained, most of whom were arrested unlawfully. The LGBT community is the most affected.

Share

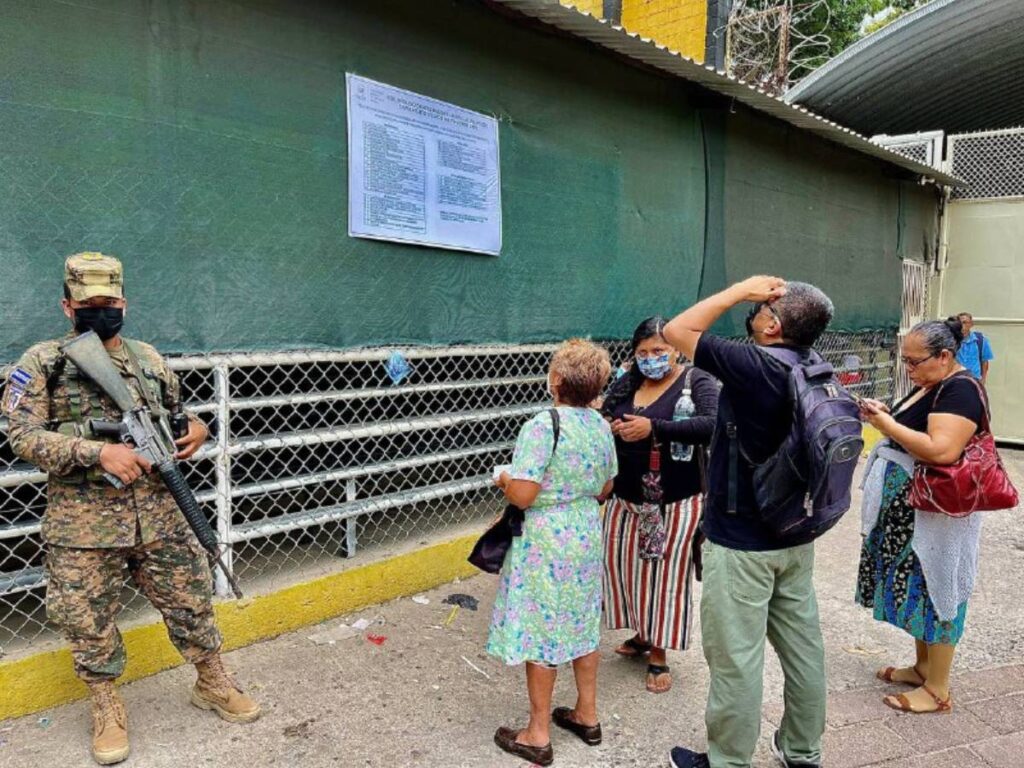

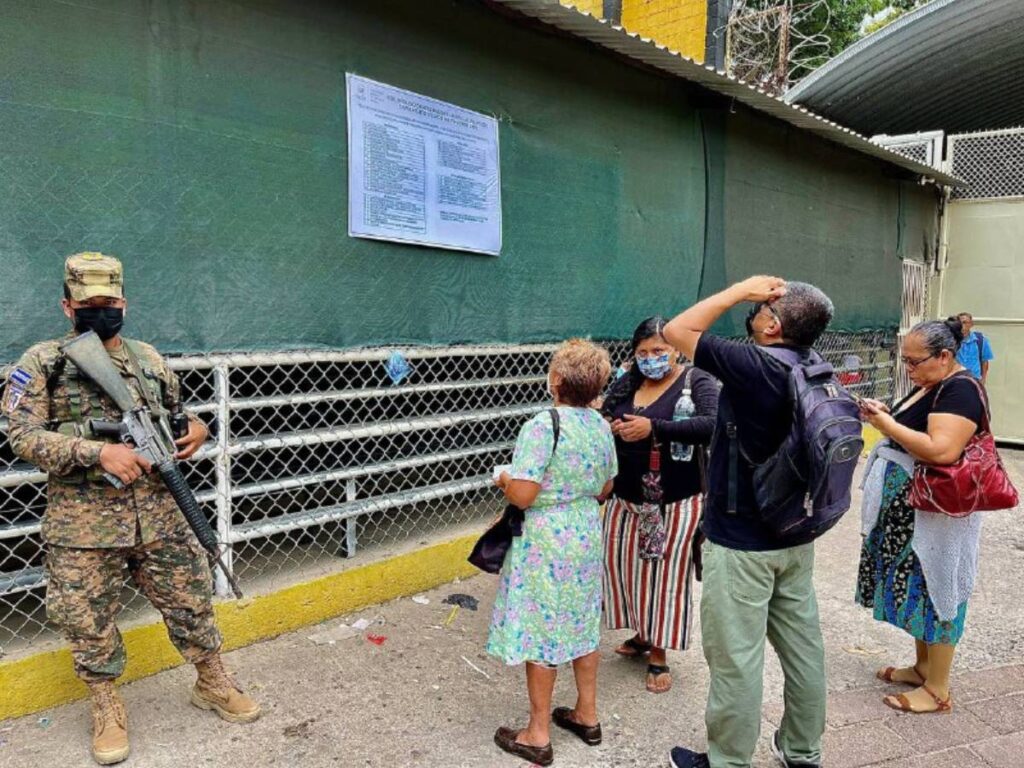

MEJICANOS, El Salvador. Hundreds of women wait in a long line outside a prison in El Salvador. They are waiting their turn to plead for information about their relatives detained during the controversial state of emergency.

Some, with teary eyes, seek answers to the uncertainty they have been experiencing since Congress approved a security emergency that suspends constitutional rights.

People sleep on cardboard, under makeshift plastic tarps strung up in the street. They eat food prepared by various churches to give to families waiting outside La Esperanza prison, north of the capital. Their common denominator is poverty and the stigma of living in densely populated areas with gang activity.

They wait for days on end in the sun and rain. They report being woken one night by jets of water being sprayed from a tanker truck while they were lying in the street. They lament that soldiers and police have threatened them to leave the area.

“A police officer told us: 'Now we have the law that allows us to arrest anyone and even kill them. We have the authority that the government has given us.' That's not fair, I'm very scared,” María Méndez told Presentes , while waiting her turn in line.

She recounts that her 24-year-old son was arrested in a rural area while working in agriculture. The police asked her to accompany them to the station for questioning and have kept him in custody since May 5th.

Since the state of emergency began on March 27, 32,529 people have been arrested. All are accused of collaborating with or belonging to the violent gangs Mara Salvatrucha MS-13 and its rival Barrio 18, in their various factions.

Reporting: Paula Rosales.

Editing: Estefanía Cajeao.

LGBTI population

Keiry Mena, a 44-year-old transgender woman, was arrested by four police officers on the afternoon of Sunday, May 8, when she went out to buy nail polish for her work. She provides services at clients' homes because she does not have a physical location.

Keiry trained as a stylist at the Solidarity Association to Promote Human Development – ASPIDH Arcoíris Trans . She also trained at the now-defunct Directorate of Sexual Diversity of the Secretariat of Social Inclusion, by order of the populist president Nayib Bukele.

According to the testimony of Esmeralda Molina, Keiry's niece, the police told her that afternoon that Keiry had been arrested because of four anonymous complaints against her. She is accused of extortion. They confiscated her cell phone that day as "evidence." Keiry lives with her mother and sister in a boarding house located in "the alley of the children," in the industrial city of Soyapango , 11 kilometers west of the capital.

The Attorney General's Office reported that they changed the charge from extortion to illicit association, without notifying the family beforehand. Keiry financially supports her mother and sister, who are now uncertain about how to pay the rent for the room they share.

Photo: Paula Rosales.

No response

Since the state of emergency began in March, the Attorney General's Office has been serving thousands of families who gather outside the building seeking help and answers that no one provides. They have heard public officials say that "they were not going to appeal for the people who have been detained."

“What they’re doing is an injustice. They took her away unjustly and without evidence, because they didn’t have any documents or reports from the people who had filed them. Nor did they have any evidence from the people the police themselves told me they had,” Esmeralda Molina Presentes

Keiry's regular customers helped her family with money to cover transportation costs. The amount of paperwork they have to complete to secure Keiry's release is endless.

The Diké center for transgender and LGBTI people has recorded the arrest of five members of its community during the nearly two months since the measure was implemented. Gabriel Fernández, director of protection and anti-violence, told Presentes

Esteban M (the victim's name has been changed to protect his privacy) is a 27-year-old transgender man who reports that on the afternoon of Thursday, April 21, police forced him off a bus for a routine check . The officers beat him and ordered him to undress to check for gang-related tattoos. He was released hours later.

In the early hours of Tuesday, April 26, 24-year-old Alessandra Sandoval awoke to the sound of police banging on the door of the home she shares with her mother in a densely populated neighborhood on the outskirts of the capital. She was arrested for failing to present her identification and taken to a men's prison.

Photo by Paula Rosales.

Stigmatization and violence

Among the main violations documented by Diké is the disrespect for gender identity. Detainees have been exposed naked and forced to be imprisoned in cells that do not correspond to their gender expression.

Sources consulted by Presentes commented that overcrowding in prisons during the special regime is unsustainable. Each cell holds between 130 and 140 people who must share sleeping space; bathrooms are also used as bedrooms.

“Many times people think they are gang members who have 'disguised' themselves to evade justice. They have been ridiculed, both women and trans men,” Gabriel Fernández de Diké Presentes

Accounts linked to police officers and soldiers spread images of trans women with their torsos bare, accusing them of being collaborators of the Barrio 18 gang.

“There is a threat to their physical integrity because, in the case of trans women, they are assigned to men who may assault them, either physically or verbally. This puts them in imminent danger,” Gabriel pointed out.

Upon entering prisons, detainees are subjected to degrading treatment. Their hair is cut, and they are paraded before government cameras in their underwear for dissemination on social media and official propaganda outlets. Transgender women are treated like the rest of the male population.

The organization CRISTOSAL documented 555 cases of human rights violations during detentions under the state of emergency between March 27 and May 19. 77.7 percent of the perpetrators were police officers.

They believe that at least 16 detainees have died during this period . It is presumed that some were beaten to death inside detention centers. Other deaths were due to denial of access to prescribed medical treatment.

“It has been documented that some die from beatings or because the prison authorities themselves do not allow them access to their documents. In both situations, the authorities bear responsibility for the violation of the right to life resulting in death,” David Morales, human rights director of CRISTOSAL, told the press.

Families without resources or information

Alessandra and Keiry's families live each day with the worry of covering the expenses incurred due to their detentions. Since their arrest, they have used their meager savings or borrowed money to meet the demands of the prisons.

“My sister used her savings to buy a phone, and I contributed all the money I had from selling clothes,” said Juan Carlos, who asked that his last name be omitted for security reasons.

Alessandra's mother's blood sugar levels spiked. With their precarious financial situation, the family has had to cover the medical expenses resulting from their daughter's arrest.

The lack of clear information about the conditions of detainees increases the uncertainty of their families who must go from institution to institution in search of reliable information about their cases.

“The information available regarding the condition of these individuals is almost nonexistent. It is severely restricted, almost always to family members. There have been times when we have accompanied family members to either the holding cells or the prosecutor's office, and they have not been given the necessary information,” Gabriel de Diké stated.

Presentes requested comments from the Human Rights Ombudsman on three occasions without receiving a response by the time of publication.

Photo: Paula Rosales.

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.