What is university life like for transvestites, trans people, and non-binary people?

The educational sphere remains a space of exclusion for diversity. The experiences of students and teachers in Argentina, Mexico, and Guatemala.

Share

BUENOS AIRES, Argentina. The educational environment is often a hostile place for many LGBTIQ+ people, especially for the transvestite, trans and non-binary community.

This is the story told by various people who, due to discrimination or difficulties in their family environment, have had to abandon their studies. However, some of them, for different reasons, have been able to complete primary and secondary school and even reach university. What happens when trans people inhabit these spaces?

Presentes spoke with trans, transvestite and non-binary students, teachers and alumni from universities in Argentina, Mexico and Guatemala to learn about their experiences in a space that is difficult for this population to access.

The figures

Schools rank third on the list of places where people of diverse sexual orientations were attacked in Argentina, below the police station and the street.

The information comes from the prologue of Travar el saber. Educación de personas trans y travestis en Argentina: relatos en primera persona , published in 2018 by Edulp (Editorial de la Universidad de La Plata), with the participation of the Bachillerato Popular Trans Mocha Celis , the Universidad Nacional de Avellaneda and the NGO OTRANS .

There , Facundo Ábalo, PhD in Social Sciences from UNLP, provides more information: 64% of trans women who claim to have recognized their gender identity before the age of 13 did not finish primary school. Meanwhile, among those who did finish primary school, less than 10% completed secondary school .

He also explains that, for the formation of the Argentine State, the aim was to consolidate a school that would equalize based on the values of the thriving nation.

“The construction of the rules governing the operation of the school system simultaneously created those abnormalities that would have to be identified, pointed out, contained, and normalized. Or expelled if it was not possible to assimilate them into a project that would tend to erase differences, not in favor of a plan for equality, but rather a plan for leveling,” Ábalo states.

Of that 10% who finish high school, a very small sector of the trans, transvestite and non-binary population reaches university, and an even smaller percentage of those who pursue post-university studies.

One example is SaSa Testa, the first non-binary master's student in Gender Studies and Politics at the National University of Tres de Febrero. However, their story highlights the difficulties of studying in an educational space that presents itself as open to gender issues, but in practice violates the rights of LGBTIQ+ people.

Discrimination

In 2017, SaSa enrolled to study this master's degree, in the same year that they made their identity as a non-binary person public and requested male and neutral treatment at the institution.

However, the professor of the subject Body and Archive, who was also the director of the master's program : " treated me with different pronouns than those I had requested, in front of the students, belittled my research work and mocked my political affiliations," SaSa explained.

Furthermore, the institution decided to appoint the same man as a member of his thesis committee. This decision was challenged by Testa due to the history of mistreatment, and he even had to request a thesis supervisor to prevent this individual from being present.

This, along with other violations he experienced, led him to activate the university's protocol against violence, as well as request an investigation and then file a complaint with the National Institute against Discrimination, Xenophobia and Racism (INADI).

“What I am asking for is that they receive gender training and also a public apology,” Testa said.

In February of this year, INADI, in line with SaSa, issued ruling No. 78/2022 resolving the complaint. “I consider that the reported conduct, regarding the feminine treatment of the complainant in the course where he was an adjunct professor, falls under the terms of Law No. 23,592 and the aforementioned related and complementary regulations, as discriminatory conduct,” stated Emilio Demian Zayat, Director of Victim Assistance at INADI, in the ruling.

Furthermore, she recommended that the university "conduct training, both for its teaching staff and for students" on topics that may involve discrimination and "adopt the necessary mechanisms so that the respective complaints are dealt with internally with a specific protocol on gender violence."

“ Access to education must be a right, not an act of resistance and endurance. Studying must be a transformative experience, not one of suffering,” concluded Testa, who is still awaiting a response from the university.

Photo: Carla Policella.

Study in Mexico

Nahui is a 24-year-old non-binary transmasculine person who lives in Pedregal de Santo Domingo, in the Coyoacán district of Mexico City.

She has been studying Modern Portuguese Literature at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) for four years: “I’m about to graduate,” she says, laughing. She chose it because, in addition to her great love for Lusophone (Portuguese) literature, she believes that with it she can “do something for the community” since “there are several Lusophone and Mexican authors who write really cool things that need to be known.”

Her undergraduate thesis is based on translating Amara Moira's book, Vidas trans. A coragem de existir (Trans Lives. The Courage to Exist). “No one else in the faculty has translated a trans person. It's not really talked about; it's still taboo. But you have to start somewhere,” Nahui .

She also recounts that at the university she attends, “there have been very strong transphobic incidents.” “In Portuguesas, there isn’t hatred, but there is a very strong apathy. When these issues are raised, nobody goes, nobody does anything. Once, I invited my classmates to a festival for Trans Visibility Day on March 31st of this year, and nobody came. I wasn’t surprised, but I was disappointed,” she says.

For her, while there has been progress in the inclusion of the LGBT+ community in university settings, there is still a long way to go. “Sometimes we feel that we have already included trans people, but of course not. What is needed above all is a very strong awareness of the issues facing the community.”

UNAM does not currently keep records of how many transgender, transvestite, and non-binary people are enrolled at the institution . When contacted by Presentes , Rubén Hernández Duarte, Director of Equality and Non-Discrimination Policies at UNAM's Coordination for Gender Equality, stated that they are in the "data collection phase" and expect to publish this information on June 28 of this year.

As resources for students, the university has the University Ombudsman for Human Rights, Equality, and Gender Violence , which is available to anyone who feels they have been victimized due to gender-based violence. Students can also learn about their university rights there.

Guatemala without records

An hour from Guatemala City, in San José Pinula, lives Aiden, a 24-year-old trans man . He works at a call center, with irregular hours, and has been studying to become a high school English teacher at the University of San Carlos of Guatemala for a year and a half. He doesn't know of any other trans people in his faculty, and at the university, he says, "there are only a few" who are trans, "but they're not still studying there."

Regarding her gender identity, she has had “certain difficulties, but more in reference to the social perception” of her. “My voice is very soft and high-pitched, and that is obviously associated with me being feminine. In my case, even though I look like a boy, there has always been this doubt from other people about whether I am a boy or a girl,” she says.

He hasn't had any problems with his classmates. "They know I'm Aiden, that I'm their classmate, that I'm a boy." However, many of the professors and other faculty members don't know about his gender identity because he chose not to share it. "It's complicated in a country like mine, which is so conservative and all, where there's a lot of lack of empathy and understanding regarding what a trans person is," he explains. He's currently in the process of legally changing his name and is worried about whether the university will accept him.

The challenge of debating with science

Leah Daniela Muñoz Contreras is a 27-year-old trans woman who also studied at UNAM and currently works as a professor there . She chose to study Biology because she “loved everything related to other life forms.” As she progressed in her studies, she realized that what interested her most was human nature, the body, sexuality, and biological conceptions of gender identity.

These topics resonated with her particularly when she was writing her thesis, as it coincided with her transition process. She is currently pursuing a doctorate in Philosophy of Science and is studying biopolitics in relation to explanations of sex and gender.

Her experience as both a student and a teacher was positive, although “it’s not the reality for all trans people at university,” she said. While studying biology, she observed how many stereotypes were taught that she disagreed with. “In a bioethics class, the topic of trans people was discussed, and they explained the categories of transsexual, transvestite, and transgender, but from a pathologizing perspective. I participated and said that I thought that table and those definitions were wrong. Luckily, the professor was willing to listen,” she recounted.

However, she also acknowledges that “there are trans-exclusionary groups at the university.” “I haven’t personally experienced anything like that happening to me, but I know that there are discourses in those spaces and that even some research centers hold events that are openly trans-exclusionary , which worries us,” she explained.

UBA, a binary register

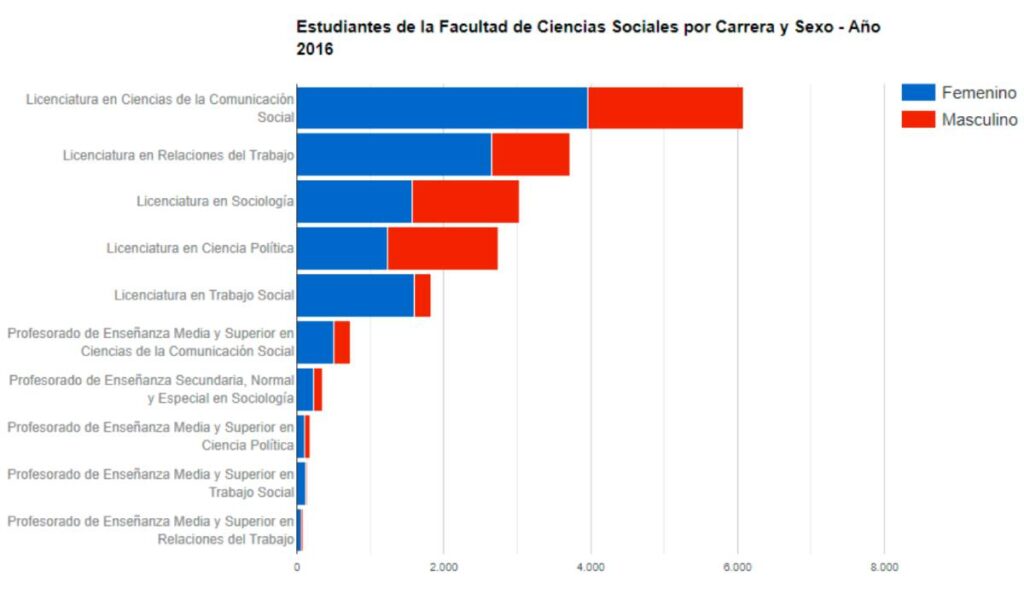

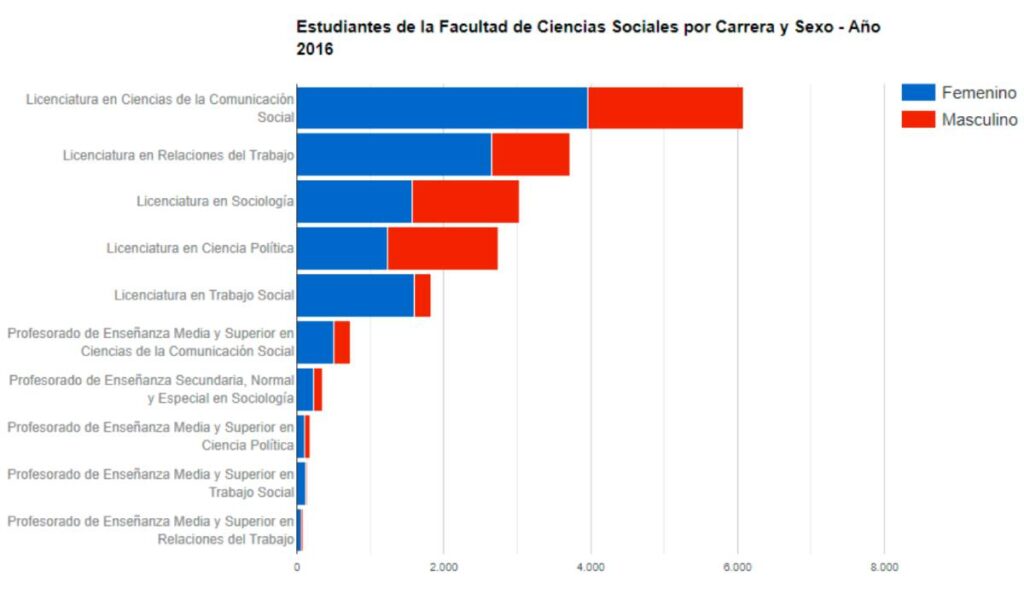

The University of Buenos Aires (UBA) is the largest university in Argentina, with 301,720 students enrolled in undergraduate and graduate programs, according to the latest data (2016) published on its official website . Ten years after the enactment of the Gender Identity Law, student registration remains binary, based on a file derived from the individual's identity document.

The Undersecretariat of Gender Policies of the Faculty of Social Sciences of the UBA informed Presentes that this problem “is being managed by the Rectorate, which is the area on which the circuit of the system depends, but even so the policy continues to be marked by this bias.”

Furthermore, they indicated that the Ministry of Women, Gender and Diversity, with the participation of the Ministry of Education, the Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation and the University Network for Gender Equality and against Violence RUGE-CIN, are developing “guidelines for the incorporation of the gender and diversity perspective in university information systems”.

“I’m very excited to have you as my teacher”

When Manu Mireles introduces himself to teach his students at UBA and UNTREF, where he has worked for 5 and 7 years respectively, he tells them: “ I am Manu, I am a non-binary trans person, this means that I am neither a man nor a woman.”

“I see faces of surprise, concern, and also happy faces. I like that it’s a starting point, opening a window to enable this dialogue,” she says. She also often asks them if they’ve had transvestite, trans, or non-binary teachers before. “Three people have told me yes in all these years, at most,” says Manu, who is also the general secretary of the Mocha Celis Transvestite-Trans Popular High School.

In her classes, she seeks to incorporate gender and diversity perspectives, as well as critically examine content, curricula, and teaching methodologies from that perspective. Her experience as a teacher has provided her with many anecdotes, some of them bittersweet due to the prejudices that surface among students.

In this sense, for her, these situations "enable us to address what still needs much thought in universities: comprehensive sex education. I believe it is urgent and necessary to think about and implement educational policies in a cross-cutting manner to guarantee a gender and sexual diversity perspective."

However, she also had experiences that were incredibly rewarding. She Presentes what one student told her: “When you introduced yourself, I didn’t know whether to cry or wait until I got home to cry. I can’t explain how excited I am to have a queer teacher. I’m a lesbian from Brazil, an immigrant. I’m so thrilled to have you as my teacher. You make me think it’s possible and you give me so much confidence, so thank you.”

For Manu, it is “essential that the university stop producing heterocissexual and androcentric mandates.” And, finally, he concludes that the historic phrase of the trans activist Lohana Berkins has been a “beacon in his life and in the historical struggle of the community”: “When a trans woman enters the University, her life changes; but many trans women within the university change the lives of all of society.”

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.