Lonko Clorinda: He confronted the Army three times and achieved a historic ruling for the Mapuche people

At 87 years old, Lonko Clorinda continues to fight for the legal recognition of her community's land, also known as "the Mapuche of the Cerro de la Virgen de las Nieves".

Share

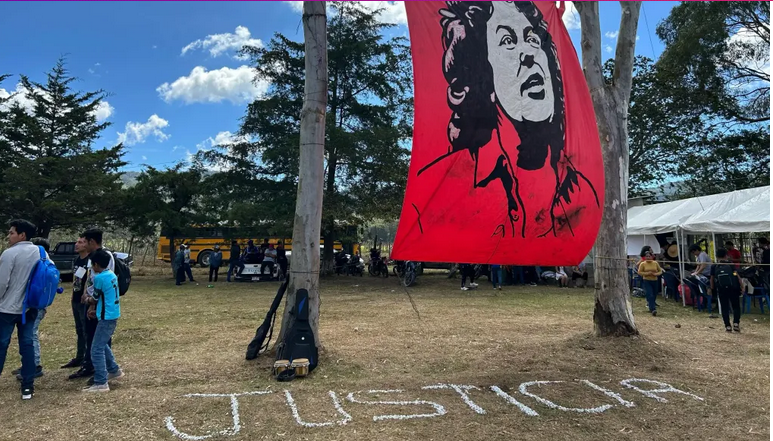

In the area of Cerro Otto and other mountains surrounding Bariloche, the struggle for land is led by women lonko, that is, political and spiritual leaders of their lof (community) Trypay Antú. One of them, Clorinda Gualmes, has resisted evictions along with her family since the time of Juan Carlos Onganía's dictatorship (1966-1970). During those years, she confronted the Army from her Mapuche worldview alongside the religious beliefs of the huinca (white invader) culture.

At 87 years old, Lonko Clorinda continues to fight for the legal recognition of her community's land, also known as "the Mapuche of the Cerro de la Virgen de las Nieves".

The conflict experienced by the Mapuche communities near Bariloche in their claim to the land is similar to that of the rest of Patagonia: they seek to recover what the genocide called the Desert Campaign took from them.

Clorinda was the first woman to join the local Mapuche council. She describes herself as persevering, deeply devout in the Catholic faith, and maintains ties with the Church of Bariloche, a clear example of syncretism. According to her, “We must integrate; we are in the 21st century. Nature is Mother Earth, but I also have great faith in Our Lady of the Snows.”

His grandfather and brother participated in clearing the land to create the ski slopes at Cerro Catedral. His son, Luis, is a werken (spokesperson) and is responsible for preserving the Mapuche language, Mapuzungun . “The Mapuche people must not lose the roots of their elders; they were the ones who gave us bilingual education. But our language isn't written; it's oral, and dictionaries are poorly written. And it's like English: it's written one way and pronounced another,” Luis explains.

The community

In the Tripay Antú community lives this large family, who have inhabited 170 hectares since the late 19th century. This area, a popular tourist destination, is located on the northeast slope of Cerro Otto, bordering Route 82 and the road to Lake Gutiérrez. There, they make jams and preserves from elderberry, apple, and plum, grow vegetables, and raise cattle, sheep, goats, chickens, turkeys, and horses.

Their productive activities coexist with the pilgrimage of the faithful to the Virgin's shrine, and with the passage of those who practice climbing and mountaineering. This peaceful coexistence was only disrupted by successive eviction attempts by the Army, on the grounds that these public lands had been ceded to them by the National Parks Administration in 1937.

“The army wanted to evict me to sell this land to the revolving confectionery shop on Cerro Otto, but I defended myself,” Clorinda explains. She becomes emotional remembering that her dying mother had asked her never to abandon the land. “And so I did. About fifty soldiers arrived with high-ranking officials from Bariloche to make me leave, and I told them I wasn't going anywhere.” Clorinda stood before the troops, recited nine Our Fathers, and the soldiers left. On another occasion, she stopped the squadrons with an Argentine flag and by painting all the posts in the area light blue and white.

The elderly Mapuche woman draws a clear distinction with the more recent land reclamations, because she affirms that she and her family never left. “These aren’t Army lands, but rather lands belonging to the national government; they occupy them. My grandfather was here before them; he helped build the Army base. My father built the pier beyond Playa Bonita, along with my brother. They also cleared the land for the runways on Cerro Catedral. We never left.”

During the first eviction, everything was destroyed: the planted fields, the new house they planned to move into on Christmas Eve, while the family fled to camp on the hill. Their daughter Elba was 16 years old and remembers the winter they spent there with her brother Luis. The second eviction attempt was during Isabel Perón's government, in 1973. And the third was in June 1983, but "since (Raúl) Alfonsín won, things changed a bit," Clorinda notes. It's a sunny afternoon; in the background, the sounds of animals and tractors can be heard.

The Colonel, the Virgin, and the Snow

Lonko Gualmes was born in the town of Comallo and arrived in Bariloche as a young child. “We are Mapuche on my grandmother's side; the Aguirre Zabala family took my grandparents' land during the Conquest of the Desert.” For her, being a “lonko” means being the head of the family. “I lead the family's ideas, work, and spiritual matters. God gave me strength and courage. I had soldiers and gendarmes armed with rifles everywhere, and I knew that one of them, right next to me, had a shotgun to hunt hares or to scare them off if they came to rob us. I always had weapons, but I never got my hands dirty. I know how to use them; my father taught me. The soldiers told me not to even think about using it. I told them I wouldn't, but that I wasn't afraid of them.”

Clorinda was five years old when Lieutenant Colonel Argentino Irusta was struck by a train at a railroad crossing. The officer miraculously survived, and in gratitude, he commissioned the construction of the sanctuary for Our Lady of the Snows. “My friend Asunción’s husband, Captain Montenegro, who had tried to evict me the first time, became ill with cancer and came to see if I could forgive him. And yes, I forgave him. And I donated that piece of land so they could build a church for Our Lady of the Snows.”

Historic ruling

Clorinda Gualmes and her family are the protagonists of a landmark ruling, the first in which the courts ordered the government to grant them title to their land. In the last ruling she signed before retiring, Federal Administrative Judge María José Sarmiento ordered the Executive Branch to "transfer ownership of the state-owned lands to the National Institute of Indigenous Affairs (INAI) free of charge within 60 days, for the purpose of their immediate allocation as communal property to the Trypay Antú community , issued in 2018, was the first judicial decision ordering the government to implement communal land ownership for an Indigenous group; until then, the only precedents had been in provincial courts.

The community's lawyer, Manuel Aliaga, has been working on this landmark case for two decades, which is now in the appeals stage at the Supreme Court because the State, through former Minister of Justice Germán Garavano, appealed the favorable ruling it had obtained.

Clorinda and her daughter were received at the time by former First Lady Inés Pertiné, wife of Fernando de la Rúa. However, the former president's early departure from office meant he was unable to sign the Ministry of Social Development's favorable ruling granting them possession of their land. At that time, the Gualmes and Ranquehue families were a single community, but they separated in 2005. Aliaga successfully obtained a favorable ruling on the administrative claim, in which the State recognized the "ancestral, current, and public possession" of the lands they have occupied since the 19th century for both families.

It was necessary to formally notify the State with an injunction to have that administrative decision recognized. Officials respond that they recognize the right to communal property but claim there is no operational way to implement the actual granting of property titles. However, lawyer Aliaga explained to Presentes that “that is not true; they are ignoring Article 8 of Law 23.302, which establishes precisely that: an operational method for handing over their land to Indigenous peoples.”

The province of Río Negro intervened, denying all property rights and refusing to recognize the legal standing of the Trypay Antú community. Therefore, the matter now rests with the Indigenous Affairs division of the Supreme Court. Powerful real estate interests are at play because, legally, the Mapuche cannot sell the land, although they can use it as owners for their subsistence and access essential services like gas and water, which they currently lack.

Mirta, Marta and Luisa

The Mapuche communities of Tambo Báez, Millalonco Ranquehue, and Celestino Quijada, also in the Bariloche area, are facing a similar legal situation. They obtained judicial recognition of their land ownership, but the Army appealed that decision. Therefore, they sent an open letter to the Minister of Defense, Jorge Taiana. “ We demand that you recognize our pre-existence as an Indigenous people and respect our rights. We find ourselves once again compelled to publicly defend what is rightfully ours. As you know, we are survivors of the genocide suffered by our Mapuche people at the hands of the Argentine state and army,” they stated in the letter.

“We, Mirta Godoy, Marta Ranquehue, and Luisa Quijada, are Mapuche women. We live and work in our community territories, and we are mindful of the history of dispossession, abuse, and constant intimidation by the Army. We can tell you our story face to face, a story you won't find in books or the media.” The three women, representing their communities, explained that “the territory has been surveyed and recognized by the National State through the INAI (National Institute of Indigenous Affairs).” They then asked, “One state agency recognizes that the territory belongs to the communities, but another agency, also part of the State, tries to dispossess us by implying that we don't exist?”

Regarding the Army's appeal of the Bariloche federal court ruling that ordered the granting of the land title to the Millalonco Ranquehue community, they stated: “We find this racist and discriminatory action incomprehensible and condemn it. It violates the human rights of Indigenous peoples enshrined in the National Constitution and in the various international treaties signed by Argentina.” And, once again, they posed the question: “Is Minister Taiana unaware that the specialized agency dealing with Indigenous issues did not appeal this ruling because it considers the claim just and believes it provides minimal redress for the genocide and dispossession suffered by the Mapuche communities?”

Godoy, Ranquehue, and Quijada stated that the Minister of Defense's actions "favor both foreign and domestic capital that appropriates vast tracts of land, water, and resources." They clarified that they are not asking for the land to be given to them, but rather "titles that would provide us with minimal security against those who seek to dispossess us."

In the letter, they mentioned the so-called Bariloche Consensus, which they described as “a racist space” that uses “false information to manipulate public opinion” to prevent their rights from being realized. Despite the emphasis placed on their case by these Indigenous women, last week the federal court in Bariloche granted the Army's appeal and halted the transfer of the land title to those 170 hectares. The armed forces argue that “this portion of the territory is essential for the development of the training activities carried out by the Juan Domingo Perón Mountain Military School.” Thus, the Tambo Báez, Millalonco Ranquehue, and Celestino Quijada communities, as well as Trypay Antú, remain trapped in the slow judicial and bureaucratic labyrinth that, in effect, delays the recognition of their constitutionally and internationally enshrined rights.

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.