Carnival, a festival and a historical refuge for transvestite and trans people

Who didn't look forward to Carnival to "go out" without fear of being persecuted, criminalized, and marginalized? Keili González, a trans activist, writes from the carnivals of Entre Ríos.

Share

ENTRE RÍOS, Argentina. Being transvestites and trans people as dissident identities is not something new in history. However, our visibility and the gains in our rights, born from weariness and struggle, make this world, designed for a select few, more habitable today.

Despite the fact that there is still a long way to go, discourses to dismantle, disputes to be fought, and policies to be built, more and more people are rebelling against a system that has assigned and imposed upon them the forms and ways of existing.

For many years, carnivals have been a "festival of liberation" for transvestites and trans people . Who didn't look forward to carnival to "come out" without the fear of being persecuted, criminalized, and marginalized?

What happened to transvestites and trans people outside of the carnival?

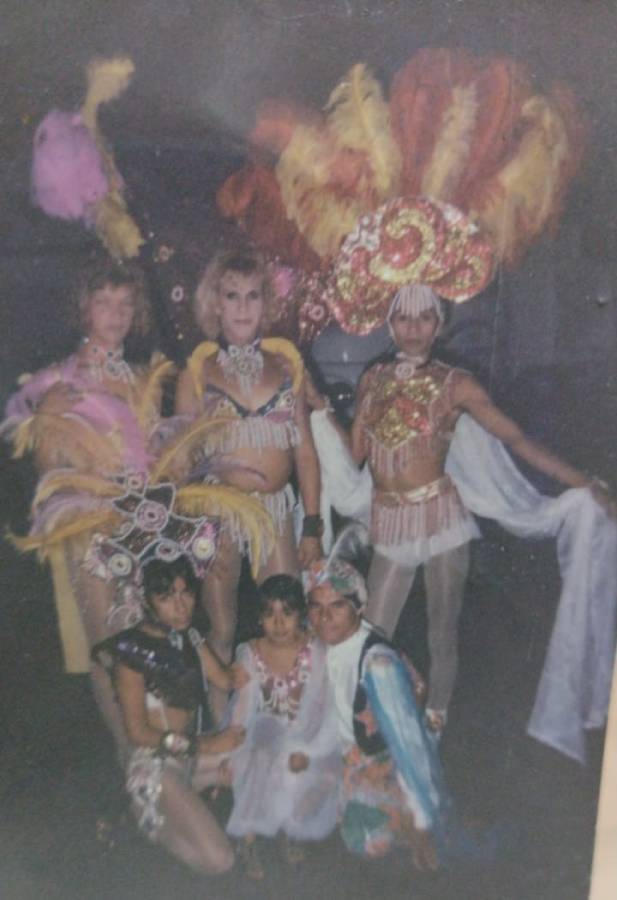

Some transvestites and trans people recount what it was like to experience Carnival and parades with the return of democracy, the clashes with state institutions like the police under the old edicts, before legal victories and cultural and social progress. They narrate their experiences and describe their perceptions.

Karen Ayelén Jumilla, known as "La Cata," is a trans woman from Nogoya who began dancing in the carnival parades in the summer of 1986 with the Panambí troupe. Regarding her experience, she recounted: "We had a terrible time. People in our daily lives mistreated us, insulted us, and abused us. We were treated like monsters; they threw stones, eggs, and tomatoes at us. They thought they had the right to hurt us."

Immediately, shifting from laughter to sadness, she added: “We felt like stars dancing in the parade, people applauded us, we were goddesses. The problem was at the end of the route, because the police were waiting for us and they'd force us into the patrol car without resistance. And we didn't resist because it was worse. The least they'd do was keep us in jail for a few days and cut our hair to ridicule us and keep us from going out to work. They'd let you out early, but first they'd gang rape you.”

Historically, police persecution of transvestites and transgender people was justified by the Codes of Misdemeanors, Minor Offenses, and Police Edicts. These regulations restricted their presence and movement in public spaces and were the primary tool of state control over this population and other vulnerable social groups.

The carnival has its manager

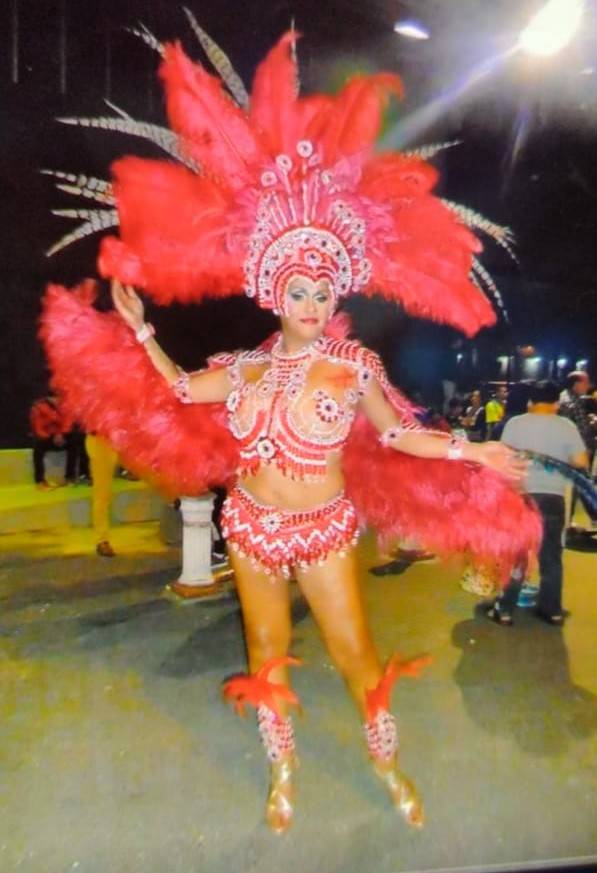

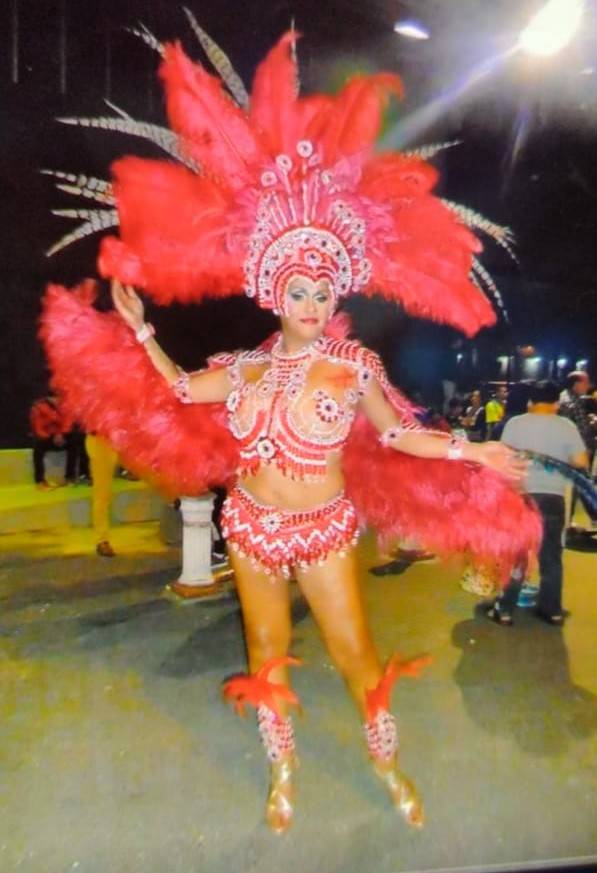

Marcel Bordón is a renowned carnival organizer in Nogoyá, Entre Ríos. At 49 years old, she is a survivor who began her involvement in the city's carnival parade in 1996 with the comparsa "Los Gurises" from the 130 Viviendas neighborhood. Today, this year's event bears her name.

When asked by Presentes about how she experienced carnivals in her early days, she said that when she went out she received as much applause as mockery, but she never cared too much, not even how they called her, and compared: "It was more difficult to be able to go out in the carnival in those days, today there is greater accessibility because the topic is talked about."

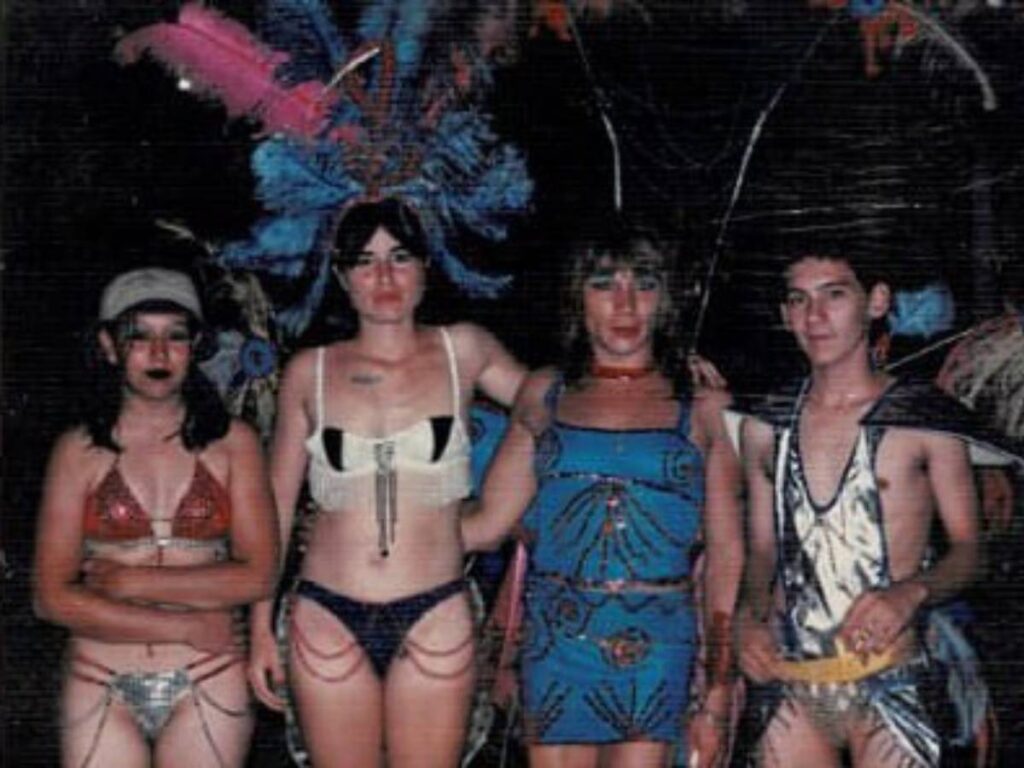

Photo: Keili González

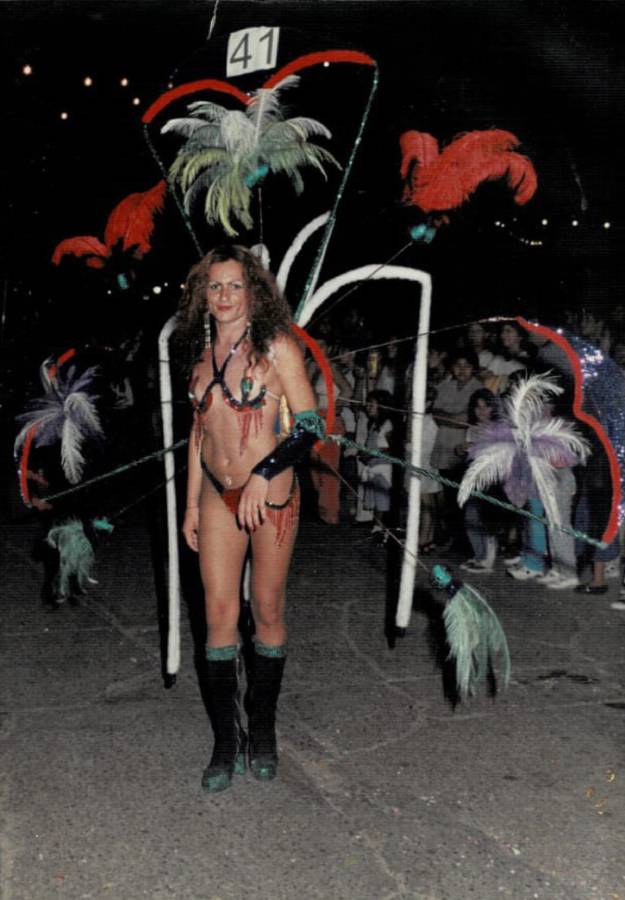

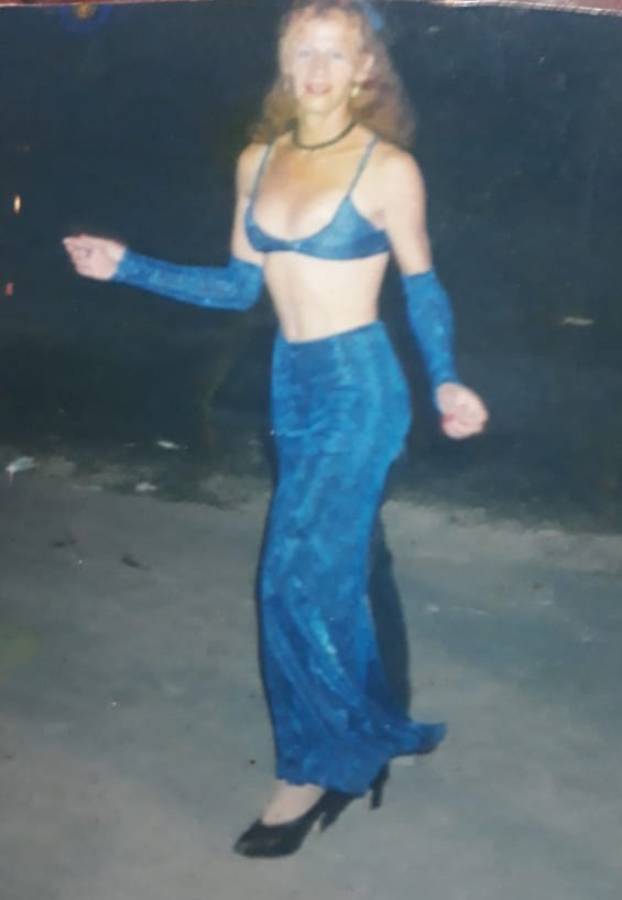

Photo: Keili González.

The bodies of the carnival

Paola López is a 49-year-old trans woman from Paraná. She recounts that she began dancing in the capital of Entre Ríos in 1987 with the Sirirí troupe : “It was somewhat contradictory because many people didn't accept us, but then they looked forward to seeing us, to seeing the show we put on. There were also those who came because we were doing what they repressed.”

She also commented that her way of dressing at that time was "ambiguous," she always showed herself as she was and for those who perceived transvestites it was difficult, they were very exposed and there were no laws to protect them in a world in which many people pigeonholed them as "men in disguise."

Mónica Estefanía Gómez is a 51-year-old trans woman who lives in Villa Rosa, Pilar district, Buenos Aires province. She began performing in carnivals in 1997 with the murga group " Los Halcones de Villa Rosa " (The Falcons of Villa Rosa).

“It was difficult for those of us who hadn’t had surgery or anything, who didn’t fit the stereotypes. There was a lot of discrimination, even more so if you hadn’t had any surgery,” Mónica explained.

Denying the existence of trans and gender-diverse bodies was and is sufficient reason to deny them rights. Capitalism and patriarchy have ensured this perfectly, by commodifying and exploiting them. They are desired, but only in the shadows.

They are desired under the camouflaged gazes at events where it was imposed to represent "stereotypes", but that desire was never expressed outside of there, it was in the public sphere.

What were the changes?

January and February were the season for fighting discrimination and police harassment simply because of the existence of Carnival. These days were eagerly awaited by the trans and travesti community. They were true celebrations. The stories intertwine, sharing a common thread: exclusion and violence for being who they are.

Regarding the work for the carnivals, Marcel elaborated: “The days were long, producing and assembling costumes; it demanded more effort. The parade was more popular, more artisanal, and it took a lot of time to put together a costume. Today, for example, you can get any glittery material and put something together in hours to go out, and those who have the means go and buy it ready-made.”

“I’ve participated in various ways. I was a samba dancer, a masked performer, I made artistic and mechanized floats, I’ve been part of comparsas and murgas. For me, carnival is a way of life, it’s a passion I feel and that I express in every edition . Today my name is held high because the carnival parades in my city bear my name,” he stated.

In this sense, “ La Cata” described the carnival parades as “intense,” since they had to make each piece individually, embroidering for weeks and days on end with sequins, beads, and eye-catching stones that could be obtained at some haberdashery. She expressed: “Today everything comes ready-made, ready to glue on. Before, at least for those of us who lived in the interior, it was difficult to get materials, even though the stores had everything.”

Nostalgically, she recalled those times: “Girls today should know that a lot of water has flowed under the bridge. Carnival was beautiful; it united all the transvestites and gay men of different ages. Working together was wonderful; while we were parading on the carousel, everything was beautiful, but when it ended, we were chased by both the police and haters. They beat the crap out of us.”

for her part , said she experiences Carnival with joy. She affirms that it's a space where freedom is experienced without fear, stating, "There, you can fly, feel unjudged; it's a celebration that allows you to forget many of the things we go through in our daily lives."

As Mónica recalled the times she would get ready: “I would go out all dolled up with hot dogs and make my bras out of birdseed. It took me hours! I hope the carnival parades don't die out and that trans girls of the new generations can have fun in a healthy way and without fear, because the carnival is fun. They have the challenge of maintaining what has been so hard for us to achieve.”

The transvestite body in the carnival scene , the body as a revolutionary issue that makes explicit the need to transform everything, because we have a great fight against the spaces to which we only serve as an icon of particularity , because it is declared that we are in rebellion until that desire is made manifest in the public space.

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.