The concept of transvesticide is gaining ground in the Uruguayan justice system

For the first time in Uruguay, the Prosecutor's Office seeks to convict the murderer of a trans person, Fanny Aguiar, for femicide and hate crime based on sexual identity (or transvesticide).

Share

MONTEVIDEO, Uruguay. Fanny Aguiar was a Uruguayan trans woman who died young, like many trans women in the country and across the continent. She was murdered by her partner on November 15, 2018, a month after the Uruguayan Parliament passed the comprehensive law for trans people, which aims to guarantee their right to be free from discrimination and stigma.

murder is the latest in a series of killings of transgender women in Uruguay . Before her, Verónica Pecoy was murdered in 2016, and long before that, seven transgender women were killed in their sex work spaces between 2011 and 2012. Most of these crimes remain unpunished.

A hope for justice

But something changed the course of Fanny's story as a trans woman: her case was brought to a public trial by her family. For the first time in Uruguay, the prosecution intends to convict the murderer of a trans person for femicide and a hate crime based on sexual identity (or transvesticide), because until now they were only convicted of simple homicide.

In Latin America, the only case in which a country's justice system used the term "transvesticide" in a trial was the murder of trans activist Diana Sacayán in Argentina. Fanny Aguiar's case could be the second on the continent. Although the hearing was scheduled for February 8, it was postponed and a new date has not yet been set.

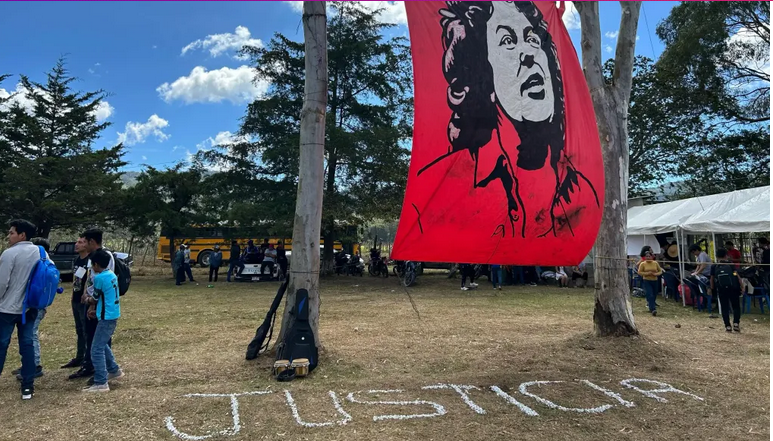

Photo: Rebelarte.

“Fanny had a life very similar to the rest of the trans women in Latin America”

Josefina González is a communicator, trans activist, and member of the Interdisciplinary Advisory Team on Gender and Sexual Diversity, which advises the Prosecutor's Office in this case. We spoke with her about this landmark trial.

– How important is the case of Fanny Aguiar's murder in Uruguay and the region?

– That a transfemicide case is going to trial is very important for us. It's the first time in the country that the family of a trans woman has initiated a public and oral trial for her murder. This didn't happen before; when a trans woman was murdered, the family didn't respond, didn't take responsibility, didn't show any interest. It symbolizes all our dead, our murdered women in the most absolute invisibility. The civil right to change one's name is very recent in our country; many of the murdered women died with other identities that they didn't recognize, they were buried with other names, because even their families didn't accept their identity.

– In these types of cases, how important is it to have a connection with the family?

– It's very important that the family initiated the legal proceedings, because it's the family that's demanding justice, and that's not common in our community. In this case, it was Fanny's sister who initiated it. It's important because we come from a background of invisibility and silence, of not being subjects of rights; we come from a time when we were the social cesspool, the most vulnerable, the most murdered, the most violated, and we're still in that situation. That a family member initiates a process like this speaks to access to justice and participation. For us, it's a case that marks a turning point, it shows a cultural and institutional transformation. It attempts to generate legal and systemic justice to frame these specific cases within legal categories like femicide, but also to introduce legal categories that don't exist at the regulatory level, such as transfemicide or hate crimes based on gender identity. This will establish legal precedent; we will work with protocols and guidelines so that the Judiciary has the resources and tools to address these cases. It also aims to promote social justice because it frames a whole process of violence that is perpetuated against our bodies and our identities, with murder being the ultimate expression of violence.

– Is Fanny's murder legally classified as femicide?

– No. The current legal classification for murderers is aggravated homicide. The prosecution is trying to argue for it to also be classified as femicide and a hate crime based on sexual identity. To do this, they need to argue these points during the trial: why it was femicide, why it was a hate crime based on sexual identity, and also add the legally unrecognized concept of transvesticide or transfemicide (they are the same thing), as was the case in the murder of trans activist Diana Sacayán in Argentina . There was significant work done by the Argentine trans social movement in that case, which is why I spoke with the colleague who advised the Argentine prosecutor's office and established a link between the national prosecutor's offices of Argentina and Uruguay. They met virtually and obtained more information and tools to delve deeper into this case, which has practically the same characteristics as Diana's.

– What are the arguments for classifying this as a transfemicide or transvesticide?

– Fanny was stabbed 50 times with a 20-centimeter knife in the face, back, chest, jugular vein, and other parts of her body. There was extreme cruelty inflicted on her body. There is sufficient evidence and information to conclude that it was a transvesticide and that her identity played a role in the murder. And, as the prosecutor in charge of the case stated, the murderer (her partner) had a deep-seated conflict with the fact that she was a trans woman. In his statements, he said that he didn't accept that she had a penis because he saw her as a woman. He has a constant need to reaffirm his masculinity, stating that when they had sex, he acted as a man and penetrated her. This demonstrates a rejection of Fanny's identity and physical being. His family also didn't accept her; they stopped speaking to him, and they had only been dating for two months. There was a sense of resistance, of non-acceptance, and of distancing themselves from that relationship. I've read the interviews with psychologists and psychiatric experts, and he always emphasizes that for him she was a woman, but then suddenly he refers to her using masculine pronouns and treats her as a man. You realize his conceptual gaps regarding sexual orientation, sexual identity, and what it means to be a trans woman. He felt rejection towards her identity, even denying it. And that's the common way people think about identity formation.

– Did the killer confess?

– Yes, although he used his problematic drug use as an excuse. The case unfolded like this: he and a friend had been using crack cocaine for two days. They took a taxi from Piedras Blancas (a neighborhood in northwest Montevideo) to her apartment to ask him for money to continue using. She sometimes gave him money; they even used drugs together. They went up to the apartment and argued because she refused to lend him the money. The friend went downstairs, and when he came back up, the killer was already killing her. The boyfriend took a while to come downstairs because he was looking for the money, and he came down with her purse and a 13-kilo gas cylinder. They murdered her and robbed her. The police arrived because the neighbors had called because of the screams, and they caught them on the spot. He confessed to the crime but justified it by saying that the drugs made him violent, and the friend said he had nothing to do with it.

– How does the fact that the killer claims he was high affect this case?

– The killer uses that argument to distance himself from the crime. This is related to his psychological and psychiatric profiles, which are connected to his life stories. They have personalities that prevent them from taking responsibility for their actions; they always blame others, looking for external blame. Due to their upbringing, their socio-familial, economic, and emotional circumstances, they became adults who lack empathy and don't take responsibility for their actions because they didn't undergo the appropriate developmental processes. While this doesn't justify their murder, it's important to consider that their lives have been difficult; they come from a history of accumulated violence. They never received therapy to overcome drug addiction. Even the killer's friend was imprisoned for domestic violence. Families fail, society fails, and institutions fail. The system produces these situations, and it's time to address this from a legal perspective. From a legal perspective, there is no examination of how the system produces crime, murderers, and violent individuals. There is only a focus on the application of the law and the imposition of punishments.

– What can you tell us about Fanny Aguiar's life?

– Fanny was 37 years old when she was murdered. She had been working as a sex worker in Spain, then returned and continued working in Uruguay. She practiced Umbanda, so she had a very close emotional relationship with Mae Trans Rihanna (a trans woman who was Fanny's spiritual mother, a practitioner of Umbanda, a religion that originated in Brazil and has many followers in Uruguay), who was one of the most important witnesses in the trial. She was her spiritual mother; they loved each other very much. Fanny had a life very similar to that of other trans women in Latin America. She was murdered young, she worked as a sex worker, she wasn't connected to any social or political network she could have referenced, but she did have a connection with other women through her religious practice.

– Why do you think I wasn't part of any LGBTQ+ group?

– That's very common for several reasons. First, because we live day to day, especially those who work in the sex industry. They don't have enough time to connect with spaces that demand time, at times when they usually rest, because they work nights or work all day in apartments. They don't have time to stop and think, to build collectively, to question themselves. This has been a historical issue for us; we haven't always been part of a collective because life passes us by. And then, because it's not in anyone's interest; people who think politically have that privilege, the rest of us don't have the training, the tools, or the access to collective spaces. Collectivizing means working on the "we." It means questioning myself, problematizing issues that affect me, what forms of violence I reproduce. And we already suffer enough pain without inflicting more on ourselves.

– What other transfemicides in Uruguay have achieved justice?

– Very few. For example, between 2011 and 2012 there were seven transphobic murders: Andrea, Kiara, La Pochito, Casandra, Gabriela, La Brasilera, and Pamela. Only two have been prosecuted; the other five remain unpunished. All of them were sex workers. There was brutality inflicted upon their bodies, and the murders occurred in their workplaces: parks, streets, forests. One of them had her legs burned; another was found in a well. These murders gained attention because they made the news, but there were many other trans women among us who were murdered by the system, by neglect, by abandonment, by lack of access to services, by being outside the bounds of legality. A form of institutionalized murder. We have many dead women whose deaths are the responsibility of the State and society. Most died young and sick as a result of violence, imprisonment, beatings, deprivation of liberty, abuse, rape, and extortion. Their bodies deteriorated from exposure to sex work, certain weather conditions, and substance abuse to sustain their jobs. You die before you die physically. We also need to discuss these deaths, how the system is absent for those who have historically been outside the system in all its forms: institutional, legal, emotional, and relational.

This article was originally published in Pikara Magazine . To learn more about our partnership, click here .

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.