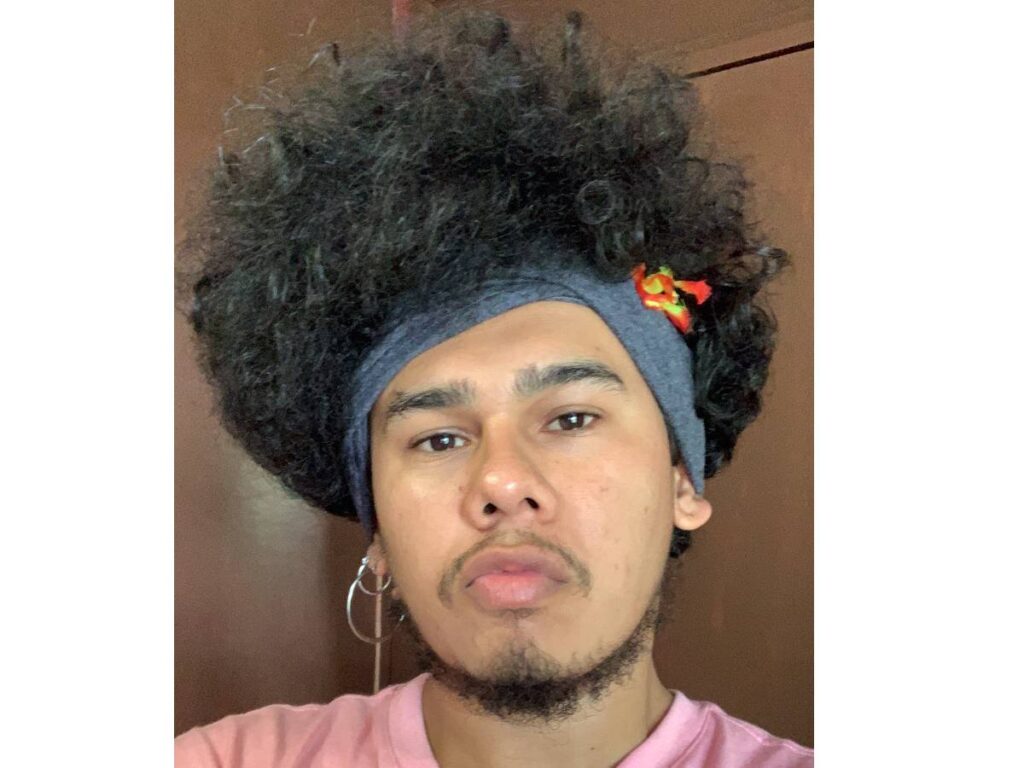

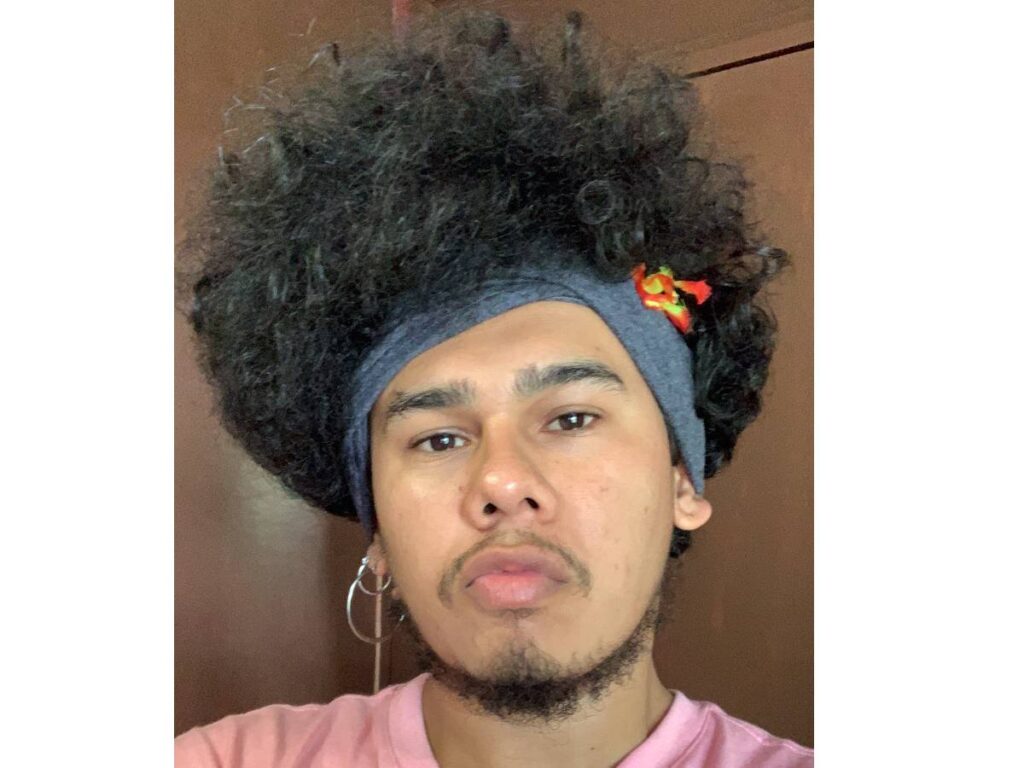

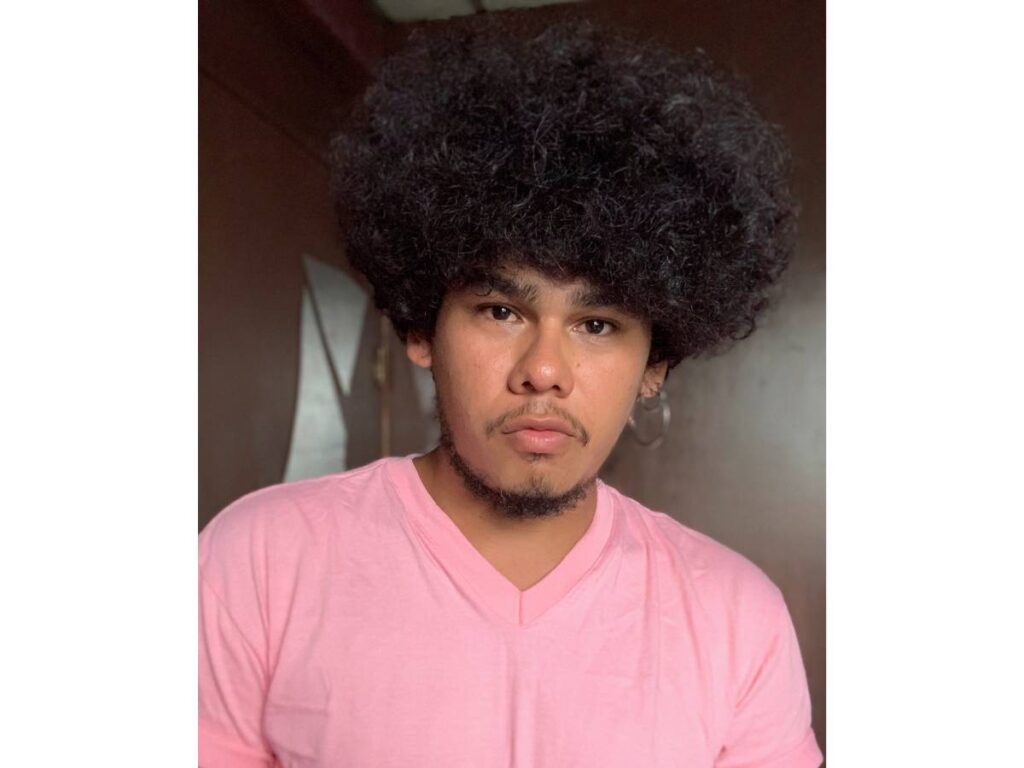

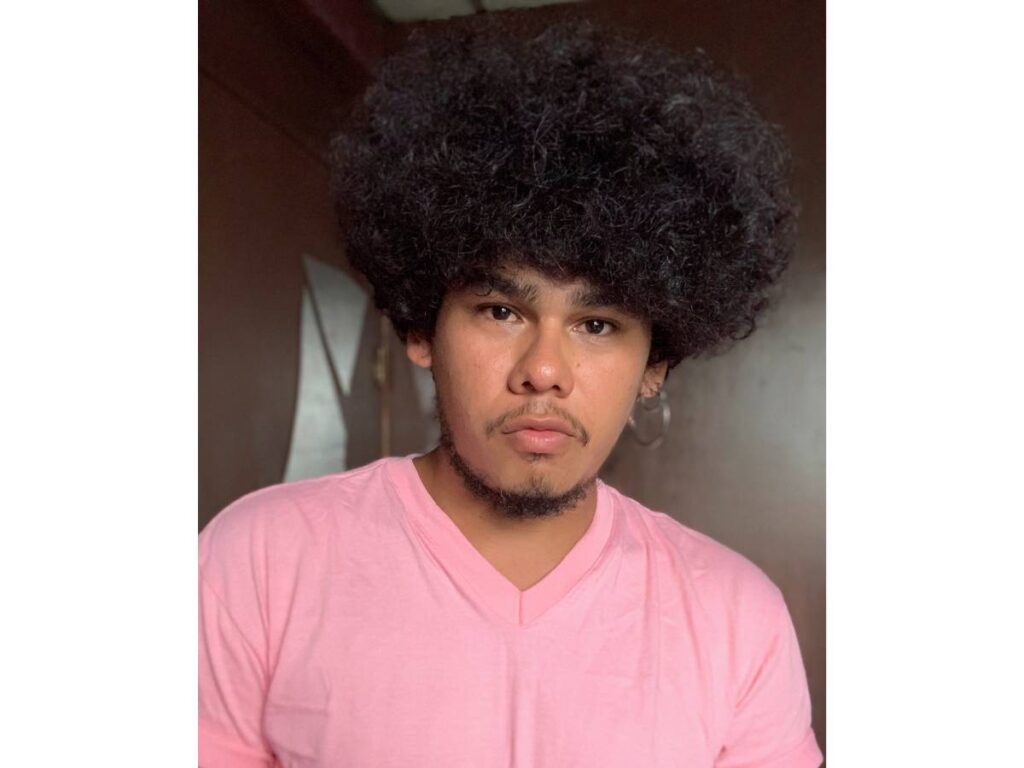

The double stigma of being Afro and LGBT in El Salvador: the story of Carlos Lara

Carlos was told to cut his hair and not make his homosexuality visible at the school where he taught English.

Share

Carlos Lara began working as an English teacher at the National Institute of San Antonio Silva, a canton located in San Miguel, in eastern El Salvador , in 2016. It was his first time working at this school, which is in his hometown. Lara spoke openly about his homosexuality, and that January, when classes began, he wore his hair short, but he let it grow out, and his curls became visible. The institute's director set two conditions for renewing his contract: one was that he cut his hair, and the other was that he stop talking about his sexual orientation.

He did not accept the conditions. Lacking a valid justification for renewing his contract, he confronted the director, citing the Teaching Career Law and the Constitution. However, he chose not to report the case to the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (MINEDUCYT).

Lara identifies as Afro-descendant in a country that renders minorities invisible. The Afro-descendant population in El Salvador is a topic not addressed in any school or university curriculum, and one that academia has only recently begun to investigate.

Begin to recognize oneself

There was a time when the young man suppressed his love for long, curly hair. He wore it short and straightened it. He felt uncomfortable with his dark skin and black eyes.

Lara's paternal grandmother has curly hair and the same skin tone as her. She shares this skin tone with her father and other aunts, both maternal and paternal. Visits to her paternal grandmother's house weren't as frequent as visits to her maternal grandmother's.

At home, she heard taunts about the dark skin and curly hair that were prevalent in the family. “Ideas of racism and supremacy also occur within families. They cause one to reject certain relatives and to love, respect, or obey others,” she reflects.

In addition to this discrimination against those who are ethnically different, sexual dissidents in El Salvador also face constant hateful LGBTIQ+ attacks or unjustified dismissals from their jobs because of their identity . They have no guarantee of state protection under the current government of Nayib Bukele.

Discrimination in the home

By 2017, Lara's relationship with his parents was strained. They knew their son was gay, but they didn't accept him. So he traveled to Tela, a city on the Honduran Caribbean coast . He was supposed to stay for a week, but he ended up staying for five months.

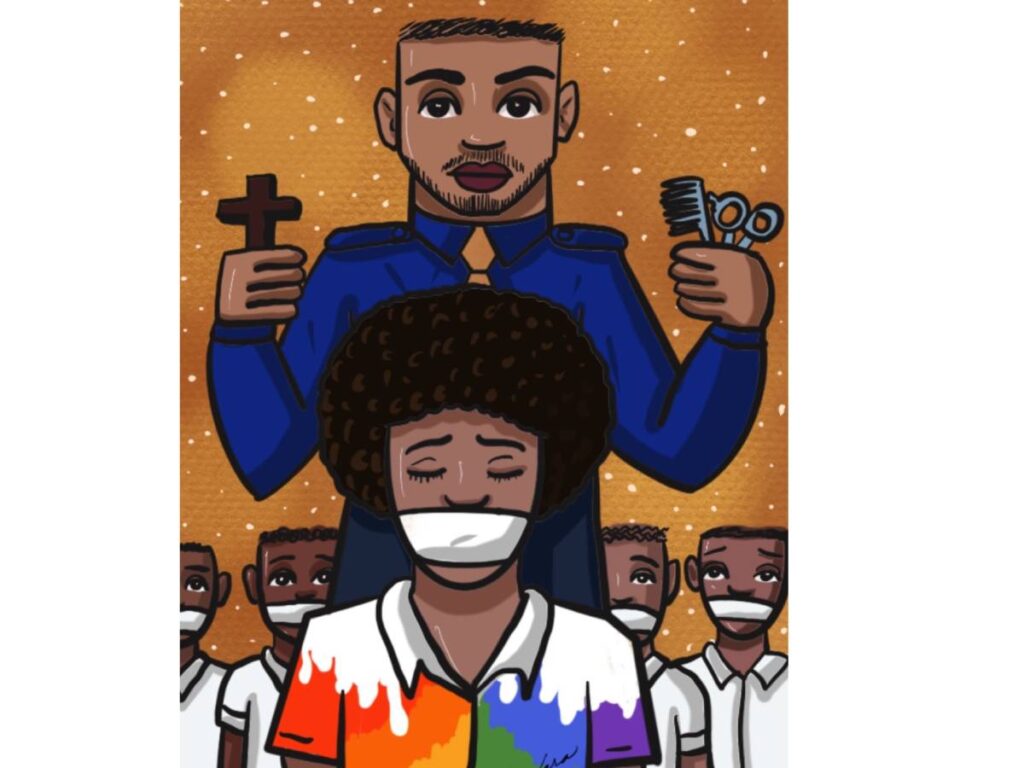

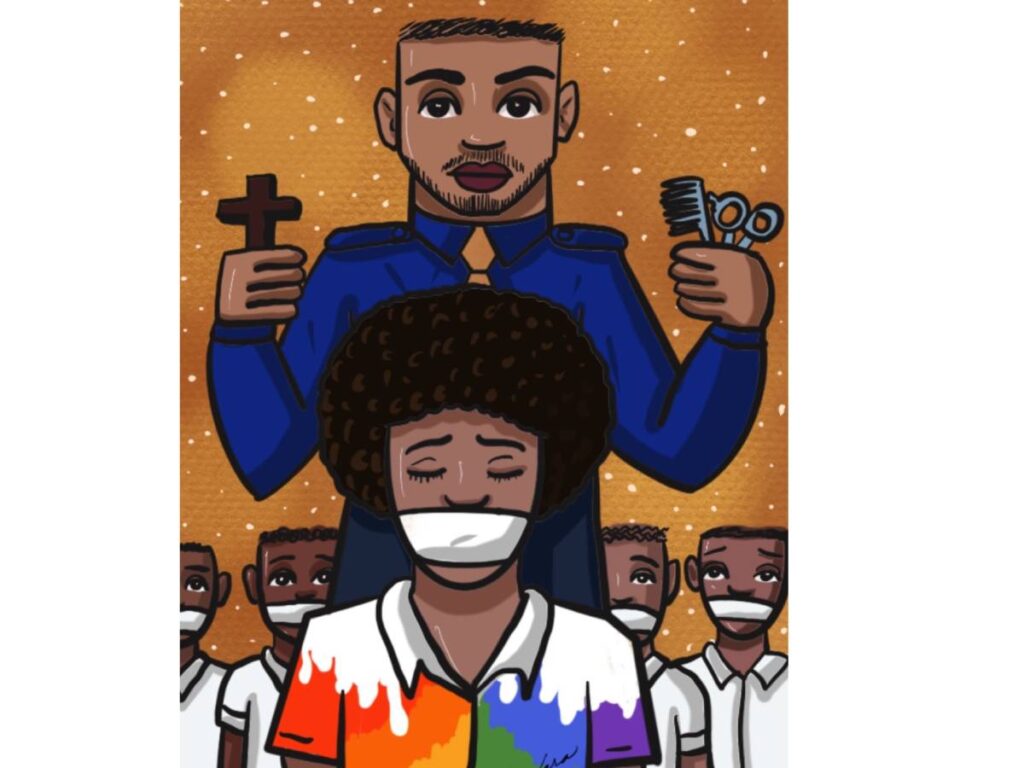

In Honduras, she met her partner, an activist, and decided to stop teaching in schools and dedicate herself fully to painting. She had been painting since childhood, but that year she moved away from painting scenes of everyday Salvadoran life to reflect LGBTQ+ hatred in her art.

Upon returning to El Salvador, life changed. His parents, with whom he had visited the Catholic church almost every day, kicked him out of the house. His father beat him twice, and on one occasion, he severely injured his jaw.

While he was in the process of coming to terms with being a gay man and being forced to distance himself from his family, Lara began to take an interest in his origins. It was then that he met Marielba Herrera, an Afro-Salvadoran anthropologist , at a presentation on Afro-descendants that she gave at the National Theater of San Miguel.

Towards the origin

Herrera remembers the day he met Lara. He saw that, among the attendees, there was a boy with Afro features, who played drums, spoke Portuguese, and wore an African shirt. And he immediately thought that he was of African descent.

After his presentation, Lara approached him and suggested that he might also be of African descent. “It’s up to you to investigate whether you are or not,” Herrera told him.

At 28 years old and lacking a family record of her Afro ancestry, the information Lara uses to assert herself as such, in addition to her physical features and those of her family, is that in San Antonio Silva there was indigo production and Africans possibly worked there.

Afro-descendants and racism in El Salvador

During the colonial period, explains anthropologist Herrera, thousands of enslaved Africans arrived in El Salvador and established connections with other people. This allowed the Afro-descendant population to grow.

Their arrival was part of a policy of repopulating the territory that occurred throughout Latin America in response to the deaths of indigenous people from various causes. The Spanish Crown intended to continue its economic growth through the labor that Africans performed in these lands.

Yohalmo Cabrera, a former congressman for the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN) , the only left-wing party, is also Afro-descendant and a retired social studies professor. He has conducted research on Salvadoran Afro-descendants. He maintains that, from the mid-1500s and for another 300 years, when El Salvador was an indigo producer, many Africans came enslaved to work on the indigo plantations.

Marielba Herrera refers to an 1807 document, written by Antonio Basilio Gutiérrez Ulloa, who was the intendant of San Salvador at the end of the colonial period. It indicates that at that time the country had a “huge” population of African descent.

In 1933, he adds, General Maximiliano Hernández Martínez decreed the Migration Law, which prohibited the entry of Africans, Chinese and other races, as a consequence of a eugenic policy taken by countries of the region in a context of world war.

The law was intended to begin "cleansing" societies and to instill the belief that Latin Americans came from a "superior race." But Afro-descendants were not expelled from El Salvador . There are documents that support the claim that people from other places could enter the country if they could justify that they were coming to work, as was the case with Afro-descendants who worked on the railroads.

A racism with a history and no record

The anthropologist states that the racism in the Central American country dates back to the colonial era.

“People say no, that we’re not racist here, that we respect everyone. That’s not true, not at all. We’re a highly racist country. When someone Black comes to the country, it’s a surprise; people even turn around to look at them because they seem exotic to them,” Herrera says.

He points out that currently, without the law of the Martínez regime, there are still immigration restrictions for Afro-descendant people.

This exemplifies a Salvadoran case of racial discrimination. In 2018, a delegation from Congo, in Africa, had been officially invited to a cultural festival, but of the group of 30, only three were allowed to enter the country.

In the 2007 Population and Housing Census , the last census carried out in the country and which showed that there were 7 million inhabitants, 7,441 responded that they self-identified as black.

However, Herrera argues that the question used to obtain this data was too broad and poorly worded. It simply asked whether people were "Black by race." It failed to include a list of indicators, such as whether there was a Black or African ancestor in the family or whether the people were born in a region with Afro-Colombian cultural practices.

Research on Salvadoran Afro-descendants was initiated in the last decade by historian Pedro Escalante Arce, and his findings have been continued by other academics. Herrera, the president of the Network of Afro-Central American Studies, has specialized in researching popular religiosity.

She points out that there is a presence of Afro-descendant populations throughout the country, in some places more visible than in others, such as the case of San Alejo, a town in the department of La Unión , near San Antonio Silva, the canton where Lara was born and raised.

More violence for being black and gay

In El Salvador, skin color determines territories and jobs, notes Amaral Arévalo, a researcher at the Latin American Center for Sexuality and Human Rights at the State University of Rio de Janeiro .

Lara, the young man from San Miguel, identifies as Afro-descendant and is also gay. This leads to even more discrimination in a racist and LGBTQ+ hateful country, where there are no laws or public policies in favor of sexual minorities.

To explain intersectionality, Arévalo draws on the work of American academic Kimberlé Crenshaw, who indicates that intersectionality is not simply the sum of negative characteristics, but rather that there are markers, such as in this case, being of African descent and sexuality, that converge and act negatively, resulting in fewer opportunities for adequate social integration.

“This situation of intersectionality will show you that you are more vulnerable to suffering more situations of violence against your body, against your identity, as such, because you have these markers that interact within you. These traits of violence increase,” says the researcher.

One of Arévalo's works is the story of Rosaura Pereira, a Honduran trans girl who arrived in El Salvador and lived between San Miguel and La Unión, two departments surrounded by beaches in the east of the country.

He found records of her in a chronicle published in 1937. She was originally from Tela and, in the researcher's opinion, this is the first case of forced migration due to sexuality in Central America, since there is no other reason that leads him to suppose that she left Honduras to work as a laundress or cook, when she could have done so in her native country.

In the images Arévalo obtained of Pereira, he appears to have Afro-descendant features. His case, he says, is a contrast between the normalized, heterosexual Pacific coast and the “abnormal” Black Atlantic coast on the other side of Central America.

As Salvadoran society develops, he adds, it also denies the possibility of ethnic and sexual diversity.

Structural violence

Ana Yency Lemus is the director and founder of the organization Afrodescendientes Organizados Salvadoreños (AFROOS) , and she is also the general secretary of the Central American Black Organization . She is originally from the municipality of Atiquizaya , in Ahuachapán, on the opposite side of San Antonio Silvia, where Lara was born.

In 2011, through the anthropologist Wolfgang Effenberger, Lemus learned that he was of African descent and organized himself with another group of young people from Atiquizaya with the goal of discovering his roots.

Three years ago, they formed AFROOS, and their main objective is for the Constitution to recognize them as Afro-descendants . El Salvador is the only Central American country that has not yet recognized them constitutionally, Lemus points out, and therefore has no commitment to public policies for them.

The organization has 20 members from across the country, including Lara, who is the deputy director. Within this group are people who have recounted various instances of discrimination they have suffered for being Afro-descendants, such as the case of girls who bathed in bleach or lime to try to lighten their skin. One of them even preferred to wear indigenous clothing so that she would be recognized as indigenous and not as a Black woman.

“We come from processes of structural racism. From an education clouded by colonialism, where we only see the indigenous, mestizo, or European,” argues anthropologist Herrera.

Racism in academia

Thus, racism also exists within academia. Herrera says she knows colleagues who, despite having decolonial or gender theories, prefer to continue denying the existence of the Afro-descendant population and their culture in El Salvador.

Meanwhile, institutions like the Ministry of Culture show no commitment to addressing the issue beyond folklore. Nor does the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (MINEDUCYT) address it responsibly. This leads to increased racism, even in schools.

Cabrera, the former FMLN deputy, also belongs to AFROOS. In 2017, he managed to gather 10 signatures from deputies of his party to present a bill to reform Article 63 of the Constitution.

The proposal originated in the youth group organized by Ana Yency Lemus and in 2019 it reached the Legislative and Constitutional Points Commission of the Legislative Assembly, where it was difficult for it to obtain the votes to be discussed in plenary.

“The Salvadoran state is a denialist state. There is a state policy of ignoring, of making invisible, the Afro-Salvadoran population,” says Cabrera, who at 64 years old claims to have only discovered his Afro-descendant heritage in 2000.

Anthropologist Herrera questions the constitutional recognition of Afro-descendant communities, arguing that the Afro-descendant population itself still lacks knowledge of its own territory. She fears that once recognition is achieved, there will be little commitment to working with them, as happened after the constitutional recognition of Indigenous peoples.

Lara's struggle in her paintings

Since coming out as a gay, Afro-descendant man, Lara's paintings have shifted in theme. He now draws and paints Afro faces and also pieces that reflect elements of African heritage in El Salvador.

She recalls that she used to create a comic series featuring people with straight hair, but now the characters have curly hair and different skin tones. “I want the paintings to be a point of reference for children, for everyone who has gone through what I went through. It’s not just about painting the Afro-descendant population to represent them, but also to empower them,” Lara concludes.

Last year, Lara began her studies in Anthropology at the University of El Salvador, the only university in the country offering this degree. Herrera emphasizes the importance of having Afro-descendants studying the humanities because, ultimately, she says, the knowledge they will generate will be theirs and theirs.

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.