Water guardians in Catamarca fight daily against the power of lithium

From road blockades to public consultations: a group of women from the indigenous communities of Atacameños del Altiplano and Antiofaco del Altiplano organized to fight against extractivism.

Share

Gateway to the sun, village of the salt flats: that's what Antofagasta de la Sierra means, a town located in the Argentine Puna at 3,323 meters above sea level. It rarely rains here, and it has just over 700 inhabitants. The town's proximity to the Salar del Hombre Muerto (Dead Man's Salt Flat) makes it the gateway for transnational mining companies seeking to extract a mineral considered key to the energy transition: lithium.

There, a group of women organized in the indigenous communities of Atacameño del Altiplano and Antiofaco del Altiplano warns about the damage being done to their territory by companies and the Catamarca government . Patricia Reynoso, Elizabeth Mamani, and Santos Claudia Vásquez spoke with Agencia Presentes about their daily resistance to the advance of extractivism, which threatens water, animals, land, and ancestral culture—a threat to life itself.

“The bodies of water we have in Antofagasta and on the Salar are a daily struggle,” says Patricia Reynoso, a teacher who lives in the village and is part of the community. Twenty years ago, when she began teaching in rural schools in the area, guided tours were organized for students to the Salar del Hombre Muerto . In that territory nestled between volcanoes and hills, the oldest lithium extraction project in the country operates, run by the company Livent (formerly FMC-Minera del Altiplano).

There were pits and vehicles were passing through, but no one knew what they were doing or what was being plotted in the salt flats. There was also a project there, established in 1997 (the same year the mega-project Bajo La Alumbrera, the country's first open-pit metallic mining project, was inaugurated in Catamarca), that was looking to expand: Fénix. There were Indigenous communities that had not been consulted, nor had permission been requested to enter their territory.

Patricia felt the need to ask questions that made those in charge of the mining project uncomfortable: How do they extract the lithium? What happens to the water? Where do they get it from?

False green rhetoric

According to research by authors Fernando Ruiz Peyré and Felix M. Dorn , lithium is part of a "green" energy discourse related to combating climate change and reducing CO2 emissions into the atmosphere. Its concentrated location in the Salar del Hombre Muerto area has attracted the attention of investors from several transnational technology companies, as well as automotive companies, due to the growing interest in producing electric cars with lithium batteries.

Over the past 15 years, the province of Catamarca has appeared on the global mining map. This territory is part of what is known as the "lithium triangle," a region comprising Chile, Bolivia, and Argentina that holds more than 50 percent of the world's lithium reserves.

Throughout almost three decades of operation, the answers to Patricia's questions are in plain sight: the 11-kilometer stretch of the Trapiche River and its floodplain, from which the mining company extracted fresh water both on the surface and underground, and which she knew in its green splendor, became completely dry.

In 2018, Livent submitted an Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) for the expansion of the “Phoenix” Project. The objective: the provision of groundwater, now from the Los Patos River sub-basin. This expansion could not be carried out without using more water. This was one of the triggers that led Patricia and many of her neighbors to start stirring things up. It became urgent to begin meeting to explore the territory and delve deeper into the uncomfortable questions. Among other actions, they began demonstrating in the town square and putting up posters with the slogans: Lithium, for whom? At what cost? The resistance was underway and taking to the streets: a turning point before and after in the defense of water, life, and the rights of the people.

“They are persecuting us for wanting to defend the land.”

The Salar del Hombre Muerto (Dead Man's Salt Flat) sits at over 4,000 meters above sea level and is the great home and dwelling place for a vast biodiversity of beings that have spent thousands of years learning to live at this altitude, with little water and abundant sun. The salt flat is also where the oldest organisms in the history of planet Earth have been found: stromatolites, vital to the planet's oxygen production in its early stages.

“Lithium is about silencing those birds. Lithium is a commodity that brings profit to others, but death to us. They take our water to obtain lithium, and all that's left is death. Lithium today is bribery, an encroachment on those of us defending water; lithium today is a struggle,” says Patricia.

Water is scarce on the Altiplano. It is the driving force behind the struggle that the Altiplano communities are waging today: all living beings depend on the trickles of water that meander through the arid landscape. Birds, fish, vicuñas, toads, rheas, pumas, llamas, flamingos, macaws—all depend on water. “They have been persecuting us, intimidating us, punishing us for wanting to defend the land, the water above all else, because it is what they need, and water is life for us,” says Patricia.

Standing on the road, she recalls that October of 2018 when someone placed a large stone in the middle of the road and many neighbors decided to begin an action that would have a great impact at the national level: a selective blockade of the passage of mining trucks.

It was night, it was cold, and the fire by the roadside wasn't enough to warm them. Patricia approached the mining vehicle driver to explain that he could pass, but his truck couldn't. They wanted to be heard. They wanted him to respect their fight for a basic right: to have a healthy environment and to know what the companies were doing in the Salar.

The Atacameño community of the Altiplano began demanding public information and claiming their right to free, prior, and informed consultation, as stipulated by ILO Convention 169. They also denounced the existence of a project that included six water pumping wells, which would supply 650,000 liters of water per hour, transporting the flow through a 32-km aqueduct to the Livent company's plant . Despite various irregularities in the Environmental Impact Assessment, the project was approved by the Directorate of Hydrology and Water Resources Assessment of the province of Catamarca.

During the road blockade in October 2018, many people came with food, firewood, and water to show their support for those leading the protest: “They supported us, but they couldn’t sign our demands. Even though they were here with us, they couldn’t demonstrate because they would lose their jobs, be laid off, or have their government scholarships taken away,” Patricia explains.

The town's mayor, Julio Taritolay, also approached them at that time. In a meeting, he donned a vest emblazoned with the phrase, "And I support my people. The Los Patos River is not to be touched." During those pre-election periods, he also issued a decree in support of the assemblies that were strongly advocating for water rights. The mayor won the election, removed the vest, and began meetings and agreements with the mining companies Porco, Galaxy, and Livent. It was as if he were following the playbook of bad governance to the letter.

“The police had the times I went to school”

In February 2019, faced with government silence, community members protested again, demanding public information, a consultation, and respect for the will of the people. After that protest, the persecution and bribery began, says Patricia, who experienced it firsthand: “The police had my school schedule to see if I was there or where I was. They started bribing people who weren't here but thought differently, offering them jobs. The mining company started looking for unemployed people and asking for their resumes.”

Fear lingered in the town, Patricia says. They still try to silence her, but even with threats and after filing a disciplinary complaint against her at one of the schools where she works, they can't. As she brushes back the hair the wind blows across her face and walks along the road, at the site of the first selective roadblock for trucks and mining vehicles, she falls silent and listens again to the passing trucks, which stir up a few birds.

Public consultations and everyday life

“Because we are all going to be affected. We are seeing the environmental damage, and that is why we have joined this movement. I ask you, what benefit has mining brought us? If you can answer me, is there anywhere in the world where it hasn't destroyed the town, killed the biodiversity?” says Elizabeth Mamani

October 2021 marked three years since that first land cut carried out by the Atacameño community of the Altiplano. In those days, Elizabeth Mamani would get up early, prepare breakfast, and accompany her daughter to school.

Her deep, dark eyes reflect a nomadic and resourceful life where she learned to do everything: today, with her small hands, she cooks dishes with llama meat and Andean potatoes that delight tourists. She also buys and sells things, knits, gives guided tours, runs a bookstore, and helps her partner Alfredo bake bread and take care of the inn with one of her daughters. Several mine workers from the Galaxy company are staying there, having come to the town of Antofagasta for the first technical and participatory meeting, part of the Public Consultation process being carried out by the Catamarca government. The goal: to approve the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) on November 19, 2021.

A few days earlier, Elizabeth approached the Mining Control Post at the entrance to the village, where the 9000 pages of book that are part of the IIA are located, along with the Executive Summary that names some of the issues in the Report.

To register for the talks and the hearing, you can do so in two ways: by going there in person or by using a QR code found in some businesses in town. It feels like a mockery of the town: the internet connection is poor, the system doesn't work, copies of the hearing information are lost on the walls of the town's stores, and it's impossible to download the reports from the internet.

The IIA is full of technical information: thousands of pages that talk about the "Salt of Life" project, run by the company Galaxy Lithium, which seeks to establish itself in the area for the next 40 years.

The goal: to exploit lithium brines to obtain 10,000 tons per year of lithium carbonate starting in 2023. The pilot plant, located on the salt flat, is already operational; the project will be 50 times larger in scale. The scale changes, the area to be occupied multiplies.

In their Environmental Impact Assessment, they describe 24/7/365 production once the processing plant is operational. The total area affected will include 9 production wells during the first two years and 2 freshwater wells. The area to be occupied: 2,000 hectares. The production method: brine evaporation in ponds. The estimated investment: US$150 million.

“We are seeing the environmental damage, that is why we have joined this movement. I ask you: what benefit has mining brought us? If you can answer me, what is there anywhere in the world where it hasn't destroyed the town, killed the biodiversity?” said Elizabeth Mamani.

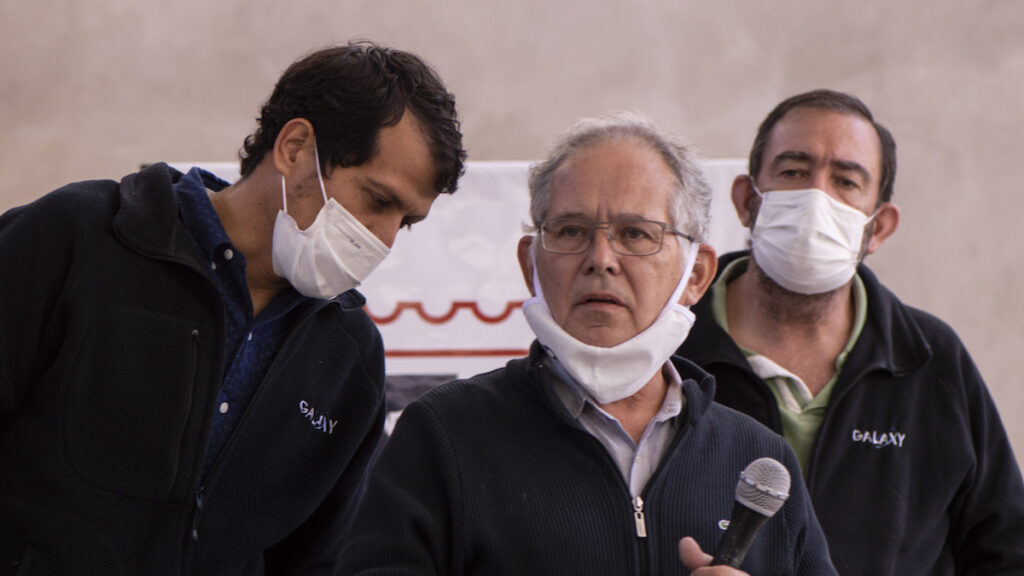

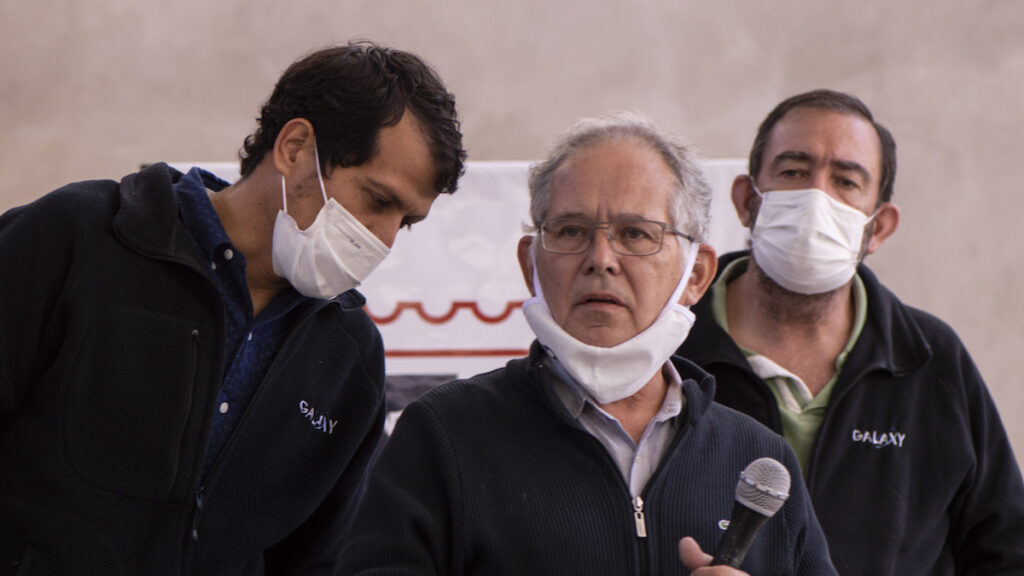

In Antofagasta, high-ranking representatives from the Galaxy company are present, as well as personnel from the Ministry of Water, Energy and Environment, the Ministry of Tourism and Culture, and the Ministry of Mining. In previous months, there were "Fridays with the Galaxy Company," weekly meetings supposedly open to public participation.

Tensions in the town have grown tense in recent days: in the days leading up to the first technical meeting, information began to circulate that put its inhabitants on alert and led to many questions for the technicians and government representatives: the fish kill precisely where the Galaxy company is building a bridge for the passage of mining vehicles that travel through the salt flat , through the contractor Huasi Construcciones on the Aguas Calientes river, at the junction with the Río de los Patos.

There, Román Guitián, chief of the Atacameño Community of the Altiplano, which has ancestrally inhabited the territory, confirmed the presence of serious socio-environmental damage. In the complaint filed by the community with police authorities, they reported the death of trout, the removal of vegetation from the floodplain, earthworks in the riverbed, alteration of the Andean landscape, and the noise of machinery affecting the biodiversity that thrives there. The first resident to speak asks about the dead fish. He is told it's not the right time. The question is repeated a couple more times until they decide to address it, and the biologist hired by the government decides to answer: the fish are happy.

A silent volcano

Doña Santos Claudia Vásquez is 72 years old and belongs to the Antiofaco Indigenous community of the Altiplano, located in Antofagasta de la Sierra. She also demands respect for the right to prior, free, and informed consultation with the region's Indigenous communities. As a child, she participated in the salt harvest at the Salar del Hombre Muerto (Dead Man's Salt Flat) alongside her father. It was a life of sacrifice, she tells us: in addition to salt, she gathered rica rica and colpa, high-altitude plants that she would then carry through the valleys of the Andean region and trade for other goods.

“Now we can’t even bring home a loaf of salt for our animals,” says Doña Santos. She continues, “No one has given them permission to do what they’re doing. Who authorized them to come here? The government? Who does it think it is? Because they’ve been given permission to sit in armchairs, are they going to do whatever they want? Why don’t they respect anything?”

On November 19, 2021, she decided to participate in the Public Hearing held by Galaxy and the Catamarca government, and to raise her voice. But she was practically silenced: the community was caught up in participatory initiatives that sought to resolve and erase conflicts and the voices of those who oppose the projects.

Co-optation of community leaders, promises of Corporate Social Responsibility and employment programs, censorship. The organization Pueblos Catamarqueños en Resistencia y Autodeterminación (Pucará), which supports the resistance movement led by the Atacameño community of the Altiplano, denounced that the hearing was not held in the town of Antofagasta, the departmental capital where most of the city's population lives, but rather in Ciénaga Redonda, a four-hour journey away. There, transportation was arranged for officials and technicians, “as well as residents from various hamlets whose support had been bought beforehand.” The day before the hearing, 20 people were hired (on three-month contracts).

Corrupt mechanisms, territorial control, and a deployment of strategies to obtain the social license of the communities living near the projects, where the volumes of lithium demanded today to supply the world market and to feed the capitalist machine in its energy transformation, are leading us to a future that, due to its voracious pace and predatory nature, seems to be unsustainable.

Patricia, Elizabeth, and Claudia Santos, like the rest of the people in their communities, know that the strength of their struggle lies in the underground veins that silently crisscross the territory. Despite the threats and intimidation, their presence becomes immeasurable in the Andean highlands.

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.