The identity resistance of Wixárika women in the lands of Jalisco

Defining themselves as "resilient," the indigenous women of the Wixárika community in Mexico fight against Western discrimination and struggle for representation in their own community.

Share

The Wixárika women, an indigenous community in Mexico that is governed by its own customs and traditions, had to be resilient.

“ That’s our life, we are resilient, we have to adapt to the new situations that Western life mainly offers us . We have to learn another language that is foreign to ours and adopt these Western beliefs,” says Sitatli Chino Carrillo, a Wixárika woman who lives in Tuxpan, in Bolaños.

This area, along with Mezquitic , is one of the two municipalities in northern Jalisco where this community is located . According to data from the State Indigenous Commission , there are approximately 14,300 Wixáritari people living in this region. The Wixáritari also Nayarit and Durango —states in Mexico.

An active and political life

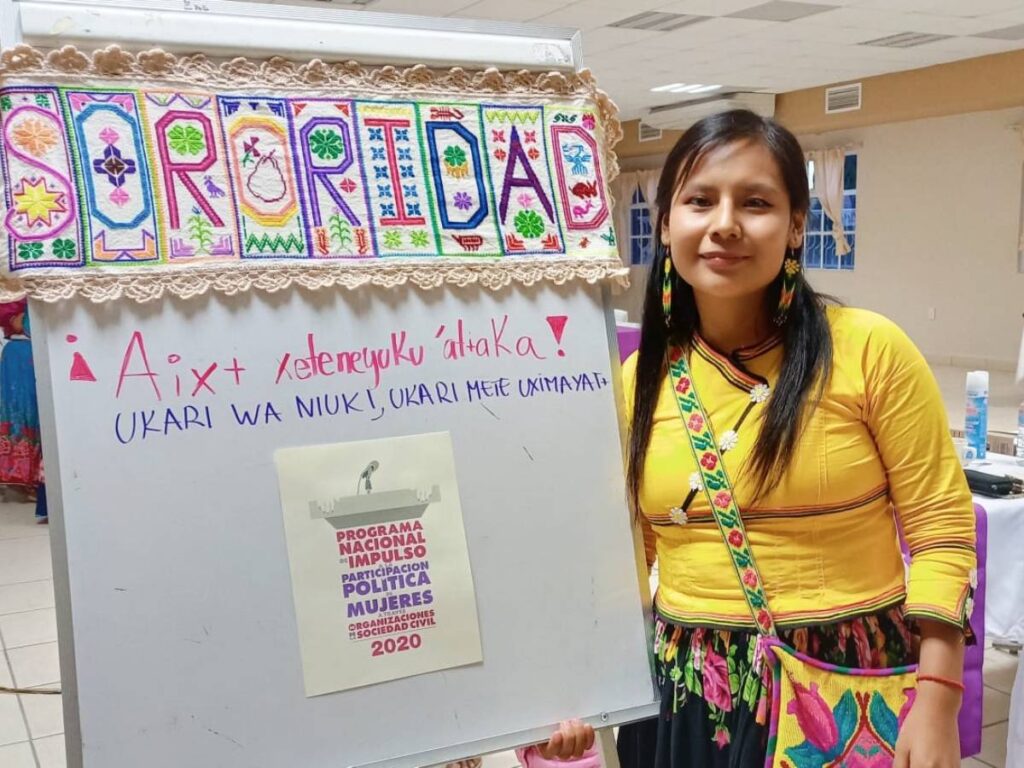

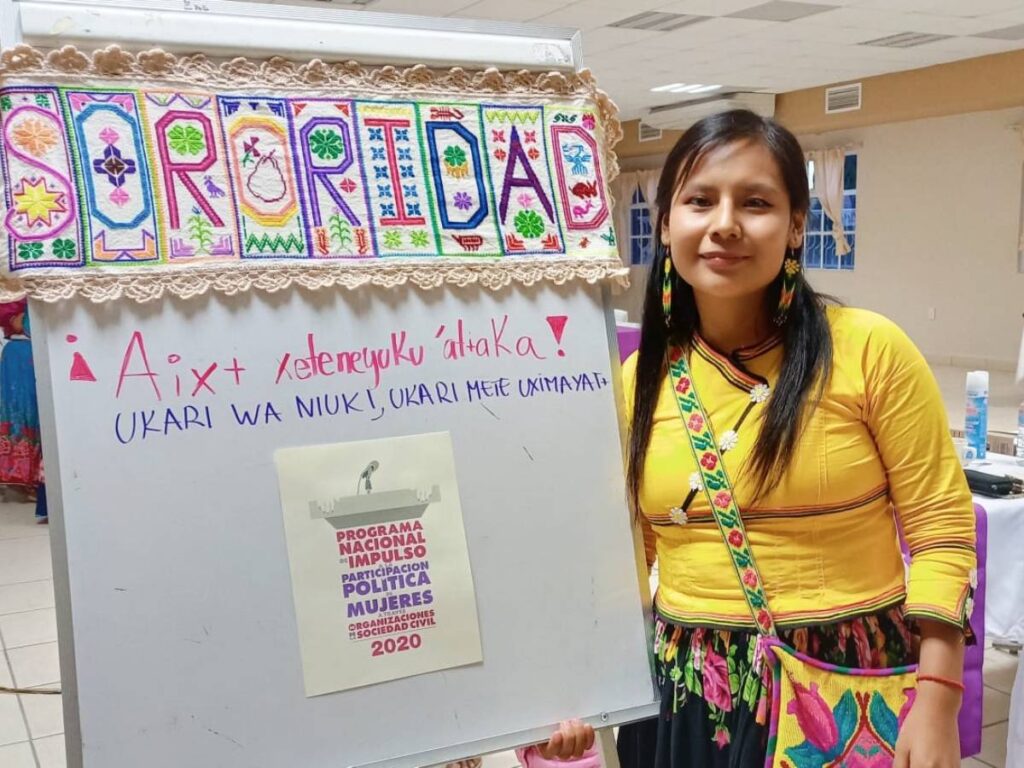

Sitlali is known for her active participation in her community. In 2020, she was appointed president of the agrarian coordination committee.

She was the first woman to hold this traditional position, for which she was nominated and elected by the residents of her community. Her role involves monitoring local issues.

In addition, she works as a psychologist in a module installed in Tuxpan by the Jalisco State Human Rights Commission (CEDHJ) where she trains traditional authorities and mainly women, so that they know their rights.

“Being a woman here in Mexico is a challenge. Now imagine being young and an indigenous woman in a place where you are discriminated against from all sides; because you speak another language, because you are not white-skinned, or because you are very young,” she explained.

According to data from the National Survey on Discrimination (ENADIS) 2017, 49.3% of the indigenous population in Mexico, aged 12 and over, perceive that their rights are little or not at all respected.

If these same data are broken down by gender, it can be seen that the reason why indigenous women most often report discrimination has to do with their appearance, their own gender (for being women) and their weight or height.

In contrast, indigenous men report that they are more frequently discriminated against because of the way they speak, their age, or where they live .

Indigenous women fight for public participation

Sitlali commented that in her community, ideas about women based on sexist precepts still prevail. For example, that women don't have the same capacity to perform activities as men, or that if they are mothers, it is their duty to stay at home.

However, they have made their way. As happened in her case, when she became president of an agricultural cooperative.

“The day the agrarian authorities were renewed, I happened to be there as moderator of the assembly. I never imagined that people would say they wanted me to take that position (…) so far I haven’t had any complications of any kind, precisely because I have demonstrated that I have the full capacity to carry out this task that the community entrusted to me,” she said.

But she is aware that this is not the case for all women within her community.

“Sometimes you can’t take a position because you’re a woman, and if they give it to you, it’s a substitute position. There’s psychological violence; they create insecurity in you so you don’t participate. They tell you, ‘Those positions aren’t for women,’ or ‘If you get involved, your husband will leave you. ’ It’s already happened that their husbands don’t let them,” Sitlali said.

In addition, their community also faces issues such as domestic violence and a lack of access to healthcare, including sexual and reproductive health education, from an intercultural perspective. These are issues that seem to be off the radar of the authorities.

There is a lack of political representation.

The political representation in Jalisco of indigenous communities and the women who belong to them is diminished, among other things, by the partisan agendas championed by the candidates.

“Many times people say they are indigenous, but when they reach decision-making positions, we are not really heard. Or they simply act out of self-interest and not for the common good,” Sitlali commented.

Another challenge lies in the difficulty of accessing decision-making positions.

Elizabeth Prado, a political scientist at the Western Institute of Technology and Higher Education (ITESO) specializing in gender issues, stated that the cultural barrier to incorporating women into politics and decision-making positions is clear, an obstacle that, she believes, is even greater for indigenous women..

“Intersectionality is very important in this sense, because not all women face the same scenarios, or have the same needs or the same resources to pursue their needs. We can’t all be put in the same box, because we don’t all have the same interests,” the expert explained.

Change means raising your voice

Sitlali said that one thing is clear to her: if Wixárika women don't raise their voices, no one will listen to them: “If we don't speak up, no one will hear about these sufferings. I believe the best way for us to resist as women is to raise our voices, to say everything we think and feel.”

She said that the organization of women in her community has been visible, and that although their participation in assemblies or traditional positions has not been so noticeable, the change is already beginning.

Now there are networks of artisans, traditional medicine experts, and women who are simply organizing to defend their rights. There are also women who have trained as lawyers, nutritionists, teachers, or nurses. However, not all of them actively participate in community life.

“We must resist and not move backwards, but rather move forward so that other women are also encouraged to participate in the political life of the community and in the various decision-making spaces,” Sitlalli concluded.

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.