Chubut: Environmentalism as a factor of popular power 20 years after 2001

Can grassroots environmentalism coordinate its expressions to become a factor in building power in Argentina? Bruno Rodríguez writes about the victory of the people of Chubut.

Share

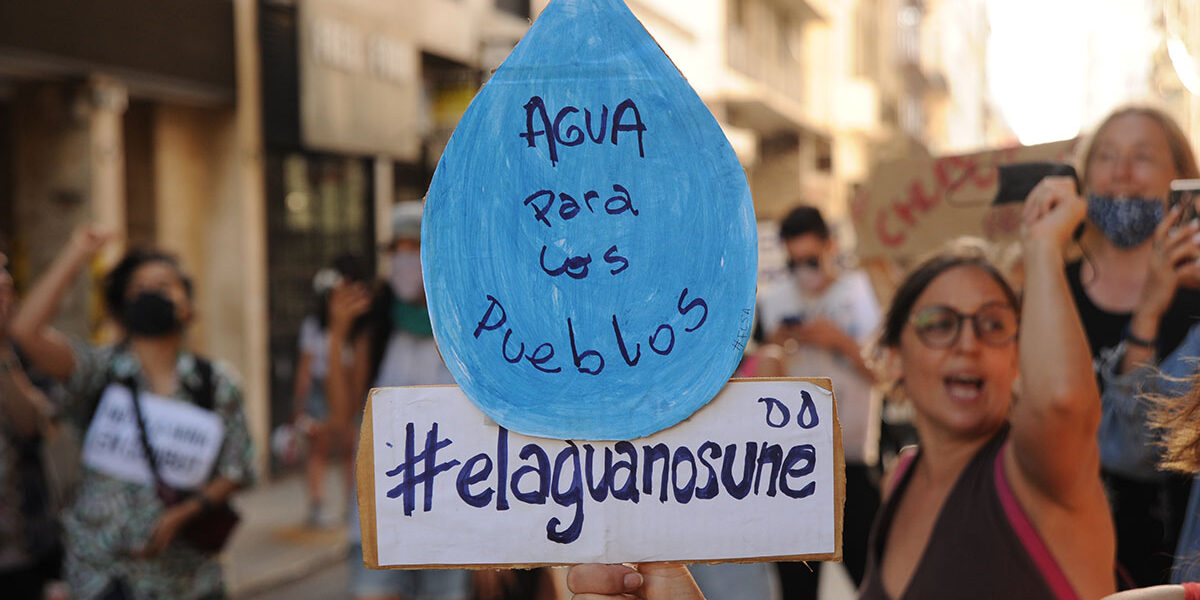

2021 ends as it began for the people of Chubut: resisting and marching, but this time, triumphing. The anti-mining victory in the province capped a year of great achievements and phenomenal progress for the Argentine socio-environmental movement. We began in a state of constant vigilance, confronting the mining initiative in Chubut.

In March, we returned to the streets for World Water Day after a 2020 that offered only the frivolous space of virtual events. We had a regressive global climate change summit in Glasgow, and midterm elections that, with great difficulty, incorporated some of the demands included in the socio-environmental agenda. Today, we are once again witnessing the catastrophic wildfires of last year, including those in Patagonia.

A political milestone

But let's recap the last great achievement resulting from the repeal of Mariano Arcioni's mega-mining project. At the beginning of the last decade, Chubut was the center of an unprecedented political experience in Argentine environmentalism. This milestone arose from a debate that swept across the entire province: mega-mining.

Today, history recounts the feat of a people who did not allow the subjugation imposed by multinational mining companies, after the repeal of the zoning project presented by the government of Mariano Arcioni and the entire local political spectrum.

To understand the current conflict, we must first review the Chubut epic that culminated in the victory of an entire people in 2003, starting with the approval of Law 5001 by popular initiative.

Debunking myths: mining

Large-scale open-pit mining refers to the exploitation of metal ores, generally through large-scale capital investment, constant material handling, and very high resource consumption. It is operated or granted as a concession by companies or consortiums of foreign-owned entities, given that the ore is dispersed in large volumes of low-concentration material, thus making conventional underground mining methods unsuitable.

Megamining first occurred in Argentina in the late nineties, with the explorations of Bajo La Alumbrera, in Catamarca and Cerro Vanguardia, in Santa Cruz.

In Chubut, the public is very familiar with the business representatives of the polluting industry they are fighting against, as well as their political spokespeople. They know about its devastating effects on vital resources like water, and also about the myths that have often been used to justify its establishment in other provinces.

Myths linked to the presumed economic benefits for the population, tied to a prevailing notion of progress that does not recognize the coincidence between maps of environmental degradation, social inequalities and economic instability.

The day mega-mining arrived in the South

By the end of 2000, news of a mining company operating in the area was already circulating in Esquel. The following year, the Huisca Antieco Mapuche community denounced the intrusion of a mining corporation into their territory, violating Indigenous rights.

In July 2002, the mining company Meridian Gold officially purchased a project located ten kilometers from the city. It had the support of the government of José Luis Lizurume (Radical Civic Union) and the mayor, Rafael Williams (Justicialist Party).

From this point, the first organizations began to form as a result of community self-organization. In October 2002, these self-managed experiences converged in a first assembly held at the Normal School.

After repeated meetings, and with a massive turnout from citizens, the Self-Convened Residents' Assembly Against the Mine was born. The founding act of this legendary Chubut resistance assembly was the call for the first mobilization against the transnational corporations' mega-mining onslaught, on November 24th. This instance of socio-environmental protest garnered an overwhelming popular majority in the streets. The slogan was simple: "No to the mine."

Victories in the streets

The social mobilization forged a plebiscite process in which the entire population was able to express itself without reservation. While the entire radical and Peronist apparatus deployed a marketing campaign that sought to place mega-mining on a pedestal in Eldorado, the residents launched an information campaign to empower their firm call to reject the sale of their natural heritage.

On March 23, 81 percent of Esquel voted “no” to mining. In referendums held in the neighboring municipalities of Trevelin, Lago Puelo, and Epuyén, more than 90 percent also rejected the polluting activity.

As a result of grassroots organizing and grassroots struggle, Law 5001 was enacted, prohibiting the use of toxic substances in mining processes . Since the 2003 victory, successive governments have continued their efforts to violate the self-determination of the people of the province and push forward with numerous large-scale mining projects.

The latest conflict

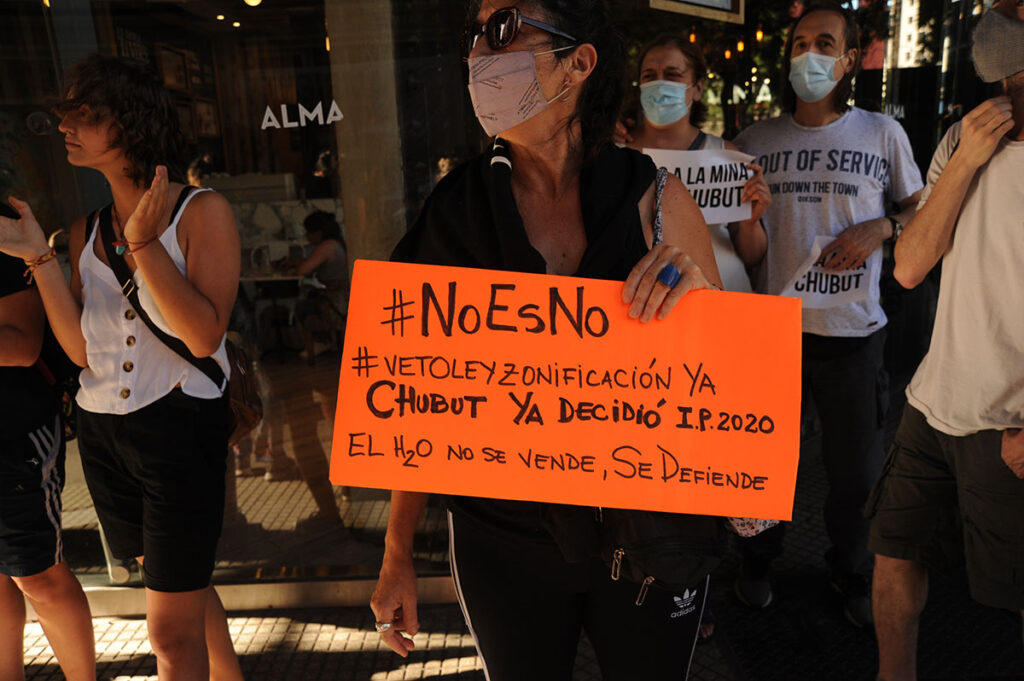

In this latest instance, it was Mariano Arcioni who spearheaded the new attempt to undermine the popular will. He did so through his mining zoning project, which aims to enable open-pit gold, silver, and uranium mining on the central plateau.

The mining initiative was presented on November 24th. That same day, the people of Chubut presented their own project, a new grassroots initiative.

While the provincial political establishment's position is based on defending the project that designates sacrifice zones, the initiative presented by the citizens is based on prohibiting metal and uranium mining throughout the province.

In the parliamentary maneuvering, the political leadership's actions revealed an imbalance in the balance of power, facilitating the mining project's passage by granting it only one committee hearing in the Rawson legislature. Meanwhile, the popular initiative was stalled during debate in three committees, hindering its entry into the plenary session.

Political interests, not popular ones

Under these circumstances, the profound distance between the socio-environmental demands driven by a clear citizen majority and the will of the local political leadership is highlighted.

The corporate onslaught not only sought to undermine the defense of the territory that the people of Chubut vehemently protected for almost two decades, but also acted as a battering ram against democratic quality and institutional deterioration.

Public servants build their representation by serving the interests of those who place their trust in them during electoral processes. At least, that's what the theory dictates. But when we talk about socio-environmental problems, the social contract and the manuals on political representation completely fall apart.

Economic power versus popular power

In Rawson, legislators succumbed to pressure from immense economic groups acting in collusion with the media and the judiciary. This is the harsh reality facing the political systems of communities struggling against extractivism.

The clash of interests is divided between the mobilization of thousands and the interests of a minority. But the disintegration of the logic and dynamics of political representation does not stem from a commitment to mega-mining. It originates in the same system that governs the financing of electoral campaigns and is shielded by the ruling elites of the state.

The imposition of its will by the large-scale mining industry is not the only expression of institutional decay. In Chubut, guarantees of democratic freedoms were violated. The ruling party deployed special commando units. They repressed the people who had mobilized earlier this year, primarily targeting young people.

They even raided the home of one of the driving forces behind the popular initiative. This shows us that the struggle waged by the people of Chubut is not a carbon copy of their 2003 victory.

industries are becoming more aggressive and increasingly adopting methods that violate human rights. They are becoming more radicalized and jeopardizing public trust in their representatives, and they are manipulating the media and the justice system. Corporate crime hides behind a smokescreen of myths about progress and development.

Environmentalism fights against the perversity of an unsustainable model, but it also advances and becomes more radical. It draws strength from new generations, from the victories of the past, and from the dreams of the future.

The question that arises lies in the challenge that all emerging movements ultimately face. Can grassroots environmentalism coordinate all its expressions to become a force for power in Argentina? Perhaps we should look to Chubut for guidance, which is offering us many lessons with its people rising up 20 years after 2001, and with an eye toward 2022.

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.