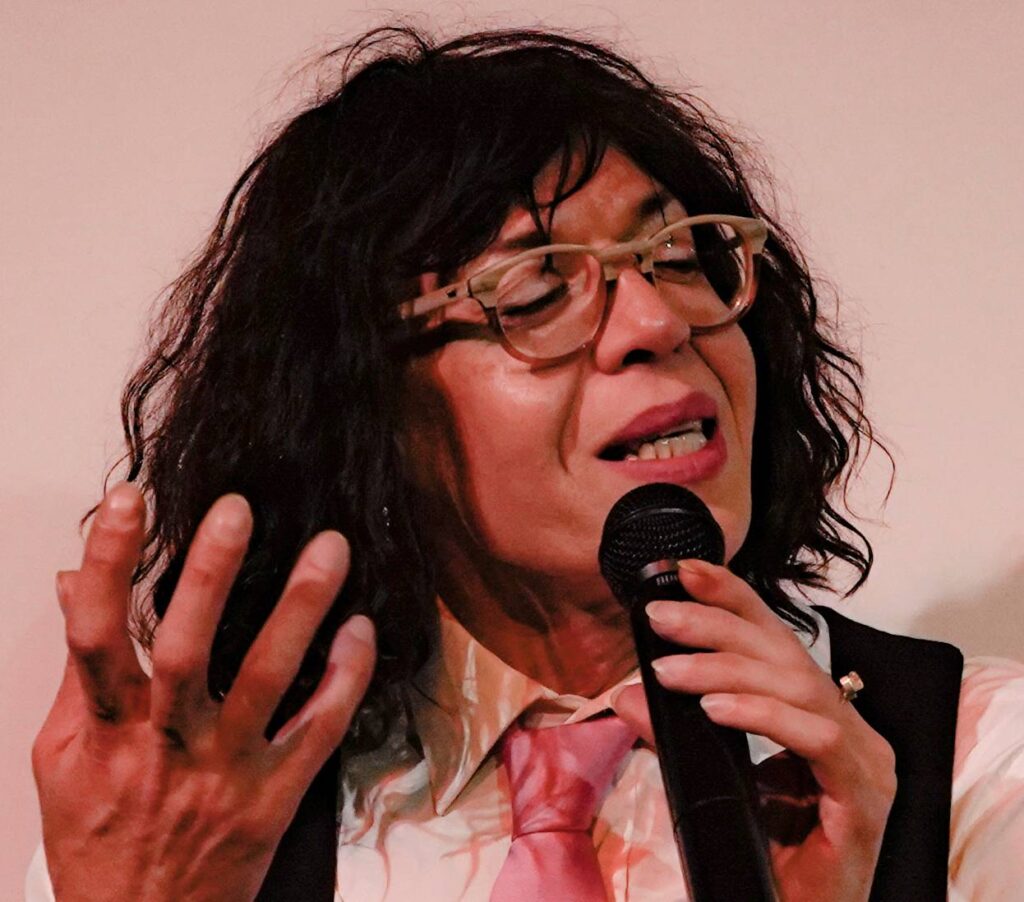

Transvestite Fury: The Living Dictionary of Marlene Wayar

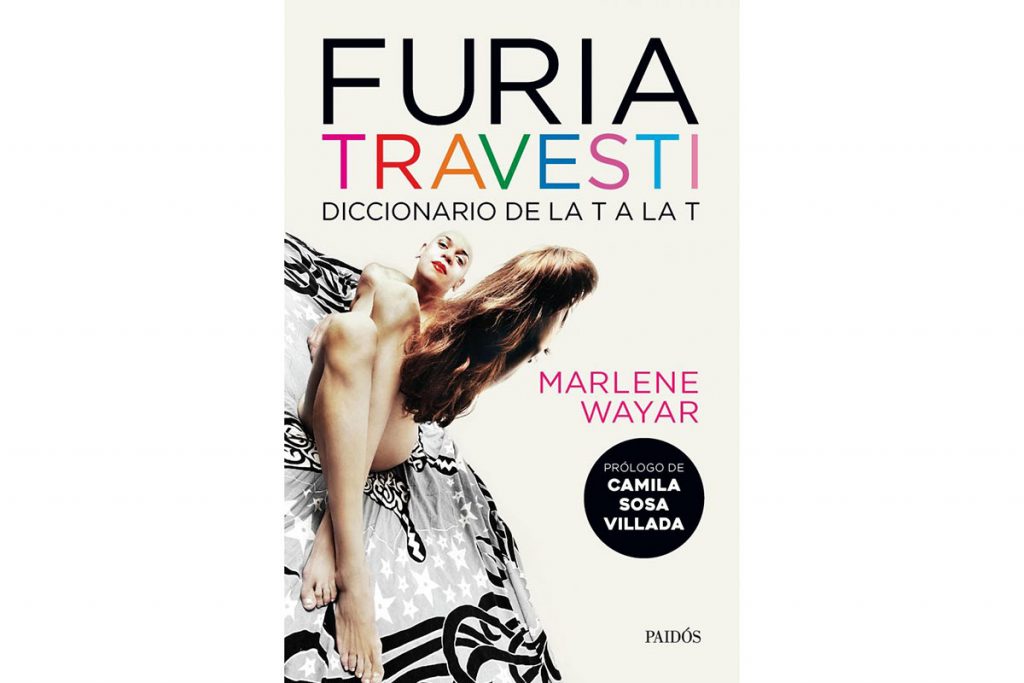

The activist edited her book Furia Travesti. Diccionario de la T a la T where she uses her own biography to trace a journey through the violence, struggles and conquests of the transvestite trans community.

Share

“Do you want to know what it means to be a transvestite?” asks Marlene Wayar, a thinker and key figure in Latin American trans and transvestite activism, in the first entry of her book Furia Travesti. Diccionario de la T a la T (Paidós, 2021), an expanded and corrected version of Diccionario travesti de la T a la T first published in 2019.

Throughout the work, "Transvestite" will be an impossible word to define. A starting point to ask ourselves about history, strength, fragility, struggle, and love.

If the traditional dictionary, as we know it, is a safe haven, explains Camila Sosa Villada in the prologue to this edition, Marlene's dictionary is quite the opposite. "It is an unsafe terrain where everything known is refuted or at least called into question," Camila writes.

This is because we will not find, in this dictionary, an absolute definition of any of the words it contains. Even the method for constructing the descriptions of these concepts will be different.

To be able to define it, Marlene resorts to memories, to passing comments, to her own biography and to the collective biography of old and new friends.

And, as Liliana Viola suggests in the epilogue, this dictionary, in a way, does not belong only to Marlene.

Their essays on definitions, their open questions, their thoughts that are more collective than individual, “have been developing since the first trans struggles of the last century to reach today, when gender identity is law and when the demand for work and human dignity crosses generations and identities.

-What does it mean for you to be a transvestite in Latin America today?

It means a constant struggle to avoid being the poorest option. It means that society shouldn't elevate us with a pinkwashing mentality, thinking that everyone likes us and that we'll never say anything that makes them uncomfortable. It means continuing to reclaim the word "transvestite," continuing to demand that this world see us from our perspective.

It's a place of synthesis because I can't say it's representative. We're such a poor community, without our own institutions, that if we stand up for anything, it's not because our female colleagues voted for us and brought us there.

The idea of being a synthesis has to do with having in mind that polyphony of voices that are the companions who are no longer here, those who are coming, and the children who demand responsibility from us regarding the world we are going to leave them.

It's an extremely strange synthesis. I don't think I have the capacity to express it or to give a definitive answer. Other generations will be able to see that, to understand what it has meant to be a transvestite in this era. We'll also see if we still exist or if we are the last.

-What, in your opinion, should an attempt at a dictionary that breaks with the classic dictionary be like?

"I don't mind the idea of a traditional dictionary, but I do believe that ongoing work is needed to make it a living tool. In other words, we need to be able to use language, guided by the dictionary as a tool, to eliminate noise in communication."

In some situations it is necessary to speak concretely and stop using failed metaphors that in some areas become extremely ineffective and contrary to people's rights.

This dictionary pursues the other objective, which is to take ownership of the language itself. Or perhaps, to reclaim our right to create that language at a political dialogue table to which we have never been invited.

It's the power to define for ourselves and to let others know what we understand by many of the terms we've seen bastardized, impoverished by their very use. Let's think, for example, of the word "mom," a word broken by daughters, by feminism, and also by us, who can break it down, expand upon it, and deepen its meaning.

This exercise in breaking down always entails a construction.

-Speaking of mothers, in the book you explain what transvestite motherhood is. Could you elaborate on this idea?

-There is a strictly community-based mothering that has to do with the exercise of mothering by adults towards younger children.

This idea stems from the very feeling of helplessness that all trans women carry, of being alone, of not knowing how to navigate an adult and unfamiliar world. The adults show you what it's like and what their experiences were, what worked for them and what didn't.

This, far from always being a romantic image, can be absolutely distorted because we are people who have been raised in this system, so we have the same imprint as any other motherhood.

Motherhood, even with good intentions, can lead to violence, a beating because you came home drunk and are wasting your time, your youth, your money. Or conversely, you can be left more vulnerable because you're a nobody, because "you have to pay your dues, this corner is mine, and I have a deal with the police or the hotel," and that's where you pay tolls. It's not all strictly romantic.

But there is also a much more concrete form of motherhood, which we could define as maternal-paternal, like that of the vast majority who support nieces and nephews, younger siblings, sending them money, setting an example, offering gestures, gifts, and educational opportunities. No one considers that when a trans woman exists, there is a family behind her that depends on her.

It also happens that these mothers, who have good intentions, suffer from ignorance, desperation, and fear—all the things that society instills in them regarding what constitutes success for survival. And so, fatphobic rhetoric that leads to bulimia and anorexia is not foreign to our community.

If one generation saw other generations as monuments to beauty and desired that, time later we were able to learn the cost of that beauty: injected silicone, deaths, amputations, pain. The inability to discuss this within the community is a problem because it leads to discourses that judge superficially, remaining on the surface and failing to delve into the fact that these mothers offer the resources they have.

You can't give what you don't have. Or conversely, we romanticize everything and think it's beautiful, and we lose the possibility of a critical perspective that allows us to question and challenge ourselves in order to incorporate tools that have been historically denied to us.

-Can theory be developed from autobiography?

-Absolutely. From biography as a personal journey, intertwined with other biographies, and from that network of biographies as a collective history. I believe that the context, even with the best intentions, has caused us to lose our history. We don't owe the Gender Identity Law to heterosexuality. Heterosexuality recognizes it, but that law is ours, as are our criticisms of it.

And within all of this, we are speaking of the Argentine context, which fortunately has been one of firmness and political autonomy from foreign influence. In the rest of Latin America, the constraints are much greater, and the discourses imposed by European and North American academia and international organizations are the ones that prevail. There, we are not allowed to think for ourselves, to construct our own history, or to appropriate knowledge.

When I do theory, I can quote Hannah Arendt and start from the idea of the "pariah," but to place her alongside Lohana (Berkins) with her sewer-bound identities. And Cristina, an anonymous friend from my childhood in Córdoba who said, "They bathed me in opprobrium, Marlene."

I will never outright reject anything simply because it comes from academia or queer theory. Instead, I will ask myself how I process it through my own body, through the biography that we are, and that is what I believe we should be allowed to do. It is what we have been demanding when we say we need a time of peace.

-What do you mean when you talk about "a time of peace"?

-They constantly pit us against each other. Whether we're abolitionists or pro-regulation, whether our bodies can defend the right to abortion or not, among other issues. And this, instead of creating a space for peace where we can talk, dialogue, delve into our history, and begin to explore the knowledge we've developed to survive, in the first place, hinders dialogue and imposes certain simplistic narratives.

We have been defending the word "travesti," but it doesn't have to be the only one. We know it's not the only one. If we are going to focus on consensus-based wording for the sake of dialogue, I don't know if it's practical to think that because we are trans, then everything else is cis.

There is a certain power in the concept of “adgender” (ad, as proximity) that would seem to offer us an alternative to the trans/cis binary, could you explain this term a little more?

This is a concept I use to distance myself from cisgender as being "on this side," because I think it's wrong to believe that, no matter how much hegemony there is, one can be completely immersed in one particular side. I don't think there is one side and another. Humanity is one.

At one point, I was living with colleagues who had children, and I saw that they were growing up comfortably in their assigned roles as boys and girls. Even so, within that comfort zone, one of the children, Federico, would draw the Argentine flag and put me in the place of the sun because he said I was the smartest person he knew.

How can I be in conflict with that, beyond the fact that my mom, my dad, my brothers, or many of my feminist friends engage in heterosexual practices?

Heterosexuality is not inherent in hate. When hate is not a gradual, drip-feeding pedagogy, there is embrace. We have a commitment to look to the future and a responsibility to build a world for children so they don't have to inherit our ruins. I don't intend to create knowledge or engage in politics from my egocentric perspective and based on my own needs stemming from my life experiences.

Based on my own experiences, I try to transform them outside of hatred. I'm suspicious of terms like cisgender or cissex because they obstruct dialogue and make other intersectional aspects of difference invisible, and that's why I propose the term adgender.

-Transvestite theory is a theory under construction. What remains to be built?

What we need is to step back from the demands and distinguish between what is urgent and what is not. What is urgent are the hunger, the exposure to the elements, and the loneliness that our comrades have endured during the pandemic. These are urgent issues, and we need to react quickly, not only to go out and demand, for example, that the justice system search for Tehuel, but also to have the autonomy to take action ourselves if the justice system fails to do so.

Apart from that, nothing is so urgent that we cannot take the time to rethink certain phrases or preconceived, empty, generalizing proposals that prevent us from seeing what we need.

-And what do they need?

We need work, but under what conditions? We need recognition of our identity, but how, when, and in what sense? There's a good chance of falling into complacency. We are a process.

I, for example, don't want to change my birth certificate because I'm not trying to hold my mom and dad accountable just because a doctor told them, "You had a baby boy." They gave me a name, and I don't think there was any ill intent because their actions throughout my childhood and adolescence have been loving. That's how they saw it; those were their tools, and when I raised the issue, they listened.

I identify as Marlene, but I'm not unaware of the name they tried to give me, with the affection they intended at the time and the care that went into filing it away afterward. That's the transvestite story. Otherwise, we become ephemeral experiences where those documents don't tell our story. That's how we won't break down the binary, the possibilities for boys and girls to envision themselves with complete autonomy, or to envision themselves in a purely submissive or dominant role, when it comes to systematized practices that aren't autonomous and that always place certain bodies in a position of submission.

It's incredibly difficult for us to break free from those structures and empower ourselves, so to speak. These frameworks are deeply ingrained in us. We must ask ourselves questions that go beyond political correctness.

At some point, one has to make peace with the system (or have a revolution, which doesn't seem to be on the horizon). In this sense, what possibilities does working at an institution like the Palais de Glace offer, given your background in trans activism?

Fortunately, it allows for both a lot and a little. The Palais de Glace is a decentralized organization and doesn't operate according to general policies, which are the subject of internal squabbles in every administration, all to see who has the biggest budget.

At the same time, it is a very interesting place because it is precisely where the State keeps its cultural heritage.

It has that narrative that until now has been super elitist, racist and so on, where certain bodies are not present and other bodies are always present as objects of study, or with a romanticized aesthetic vision, but never as creators.

In the last competition organized by us, the 8M competition, whose heritage belongs to us, a transgender person won the prize for the first time among the contestants, anonymously and based on an evaluation of their work. This opens up new possibilities in the field of education, where historically the museum has been limited to displaying and exhibiting.

It allows us to shift towards new actions to transform the museum space into an informal education space where we will try to make young people, children, feel it as a place to turn to.

In principle, a space where they can come to meet, occupy their time and be fully assured that there is no adult world that will violate them, but rather that will open the door for them to explore it from their own perspective.

We don't have all the answers, but we have ways of searching for those answers and thinking about them together.

That's it: being in the small circles and having a big impact because it's not yet a territory pulled in different directions by the interests of mainstream politics. Not being so closely watched allows us to do that: to invite new voices to explore what art is, and if they're interested in communicating from that perspective, to be able to do so.

-So, how do you make peace?

-Learning to navigate pain. Resisting the immediate, which is evasive. This society, before continuing to make quota laws with tendencies towards the incorporation of the transvestite-trans community, must be put on trial for the genocide that was perpetrated against us and the rest of the dissidents.

It has to listen to the stories, preserve the memories, create institutes of memory, erect monuments to us, and foster a culture that works permanently and intimately with education to remember who we were and what we did in a concrete way.

From there, and only from there, will we be able to safeguard the gains we have made: inclusive schools, inclusive health centers that think of trans health as comprehensive, complex health, like that of any other human being.

And that the way we are approached when we have a broken foot, when our teeth fall out or our liver fails, involves a way of approaching that is humane, respectful, without a face of horror and contempt.

We have, for example, a family that isn't related by blood but with whom we could share social services, and that family isn't officially recognized. We could ask ourselves how to legalize and legitimize friendship as a bond of dependency as valid and equitable as marriage, motherhood, or siblinghood.

Why doesn't our primary and most valuable form of relationship have a legal and legitimate status? Otherwise, health, or any other sphere, becomes a tiny, inaccessible box, full of privileges.

Wayar is the coordinator of the Education area of the National Palace of the Arts, Palais de Glace.

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.