In 2021, the dispossession of land from indigenous and peasant communities in Paraguay accelerated

Violent evictions have intensified in recent months, following the approval of the Zavala-Riera law: women and girls are the most affected.

Share

The last few months of 2021 have been very difficult for peasant and Indigenous communities. Violent evictions have continued unabated throughout the pandemic and intensified after the passage of the Zavala-Riera Law. This law amends Article 142 of the Penal Code, criminalizing the struggle for land rights.

According to the Paraguayan Human Rights Coordinator, in recent months there have been 12 cases of evictions against Indigenous communities, at least 10 of which were violent, and 10 cases of evictions against peasant communities: some 2,500 people were dispossessed of their homes. All the operations share the same characteristics: destruction and burning of homes, food production, their chapels or sacred temples, and theft of belongings and/or small animals.

In recent months at least 2,500 people have been evicted from their lands.

To date, land distribution in Paraguay is one of the most egregious in the region in terms of inequality: 85% of the land is in the hands of 2%. To understand what happened to the lands that were supposed to be allocated to Agrarian Reform, you can consult the Report of the Truth and Justice Commission .

The eviction operations are being carried out with a heavy police presence, water cannons, and helicopters. The entire police force has acted with extreme violence in each and every eviction in all the affected communities, according to what some of the affected families told Presentes, and which can be verified in their video and photographic documentation.

The Hugua Po'i community, of the Mby'a Guaraní indigenous people, was evicted on November 18th in the middle of a rainy day. This is another instance of institutionalized violence against women, as they are the ones who maintain the care networks within the communities. A kind of disciplinary force weighs heavily on them and children, particularly in the face of the dispossession of their territories.

What the new law says: free rein for land grabbing

The bill's authors, Fidel Zavala of the Patria Querida Party and Enrique Riera of the Colorado Party, both known defenders of large landowners, led a campaign with agribusiness executives under the slogan: “Property is not to be touched.” In record time—less than 24 hours—it was approved by both houses of Parliament. On September 30, it was enacted by President Mario Abdo, heir to the Stroessner dictatorship.

With this amendment, Paraguay increases the prison sentence to between six and ten years for people who want to reclaim their territories or protect the places where they live. This primarily affects communities occupying lands that were intended for agrarian reform. It also affects Indigenous communities, who will be criminalized for fighting for a piece of land.

The gravity of this situation lies in the fact that land ownership is not being questioned, only possession. In this way, many agribusiness owners, ranchers, and landowners who acquired land irregularly are now taking refuge in this law. As possessors of the land, they can request eviction from the prosecutor's office, without any need for an investigation into their ownership status. What is the true aim of this project that criminalizes the struggle for land?

Women and children, the most affected

Of the at least eight evictions carried out since October, two occurred a few weeks after the Zavala-Riera law was passed. While videos of homes and farms being destroyed and burned go viral on social media, very few media outlets report on the harsh reality faced by peasant and Indigenous families.

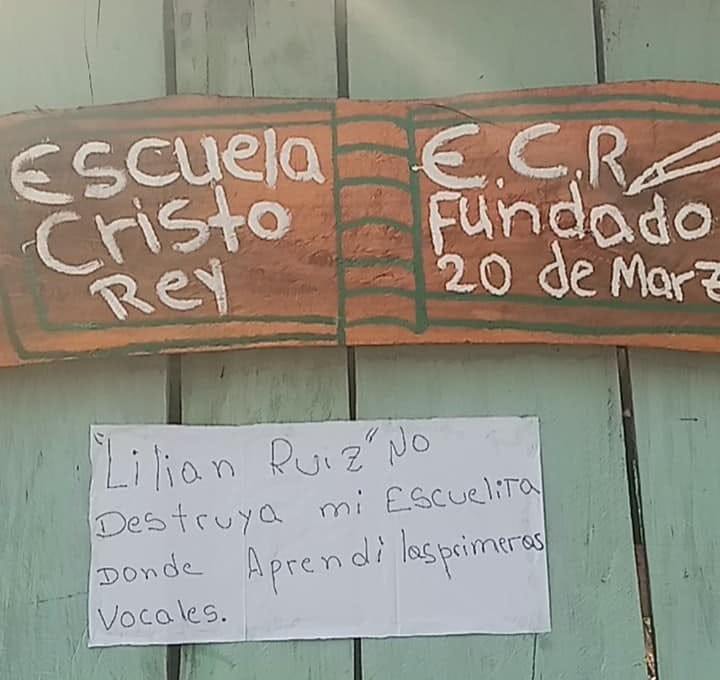

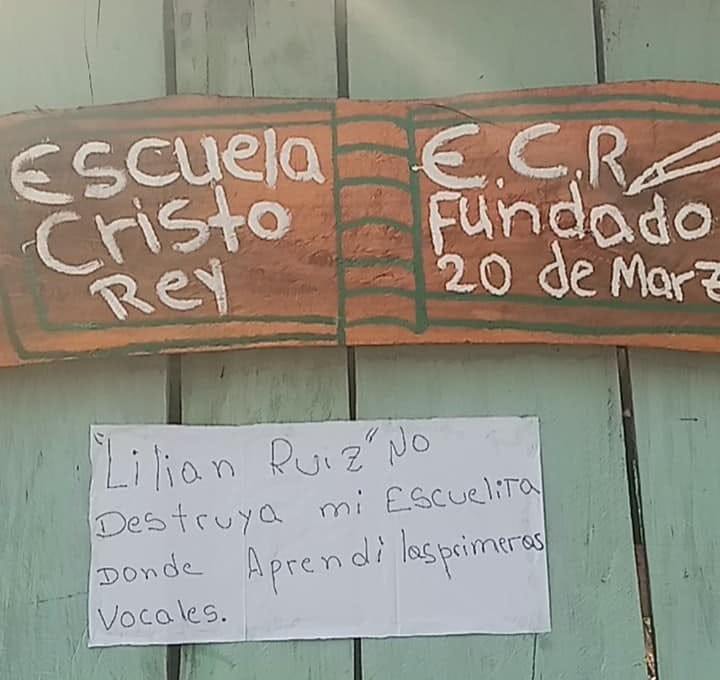

Some of the peasant communities evicted are: Cristo Rey; María de Esperanza; Edilson Mercado; Comunidad 26 de Febrero; and the 29 de Julio settlement. The indigenous communities are: Hugua Po'i of the Mby'a Guaraní people; the Cerrito community; and the Ka'a Poty community of the Ava Guaraní people. The latter was evicted twice in less than five months: on June 15 and November 4.

Both the photos and videos circulating on social media show peasant communities and indigenous peoples with only the clothes on their backs and a few minor belongings, standing on the side of the road or highway, helplessly and in total vulnerability watching the destruction of all their possessions and years of work.

Rosa Acuña is a peasant woman from the Cristo Rey community in the department of San Pedro, and Marta Diaz is a leader of the Ka'a Poty indigenous community of the Ava Guaraní people in the department of Alto Paraná. Both of their communities have suffered violent evictions. Rosa's community is currently camped out 500 meters from the land they are claiming, and Marta's community is protesting for the second time this year in the Plaza de Armas in Asunción.

Approximately 70 families from the Cristo Rey peasant community in the department of San Pedro were evicted on October 28th in an operation involving 500 police officers and trucks. This was one of the first evictions following the passage of the law that criminalizes those who fight for a piece of land.

Rosa Acuña, a community leader, recounts the cruelty with which they were evicted after 12 years of occupation. “They tried to evict us many times over the last 12 years, and they did it after the law that criminalizes us was passed. Now we are criminals for fighting for a piece of land. The government told us it would be a peaceful eviction, but it was a lie. They burned down the children's school, the chapel, our crops, and what they didn't burn they stole, including our animals. We didn't have time to take anything.”

Without any protection

Women, girls, and boys are always the most violated and their rights are violated in this context because the Paraguayan State does not provide any kind of support or compensation for these human rights abuses.

“As mothers, we see that the burden of the eviction falls on us, because we have to hold back the tears of our sons and daughters who ask us why they don't want them, why there is this difference towards us and not towards other people. We women have to comfort our sons and daughters, our partners, our mothers, the elderly,” Rosa says, recalling the day of the eviction.

No competent authority from CODENI (Municipal Councils for the Rights of Children and Adolescents) was present at the evictions. Rosa also told Presentes that during the eviction they were intimidated by Hugo Samaniego, director of human rights at the Ministry of the Interior, who told them they had no rights to the land and had to leave. He himself was present during the eviction of the Hugua Po'i indigenous community in the department of Caaguazú.

“The children get sick and ask every day: what day are we going back to Ka’a Poty?”

Furthermore, the indigenous community Ka'a Poty was evicted from its ancestral lands twice in less than five months, in a rigged process of corruption, according to lawyer Milena Pereira, a member of the Platform for Memory, Human Rights and Democracy that accompanies the community, who spoke to Presentes.

The first evacuation took place in June during a very cold winter storm, leaving people exposed to the elements for an entire night. As a result, a baby became ill.

Marta recounts a similar reality to Rosa's, her voice filled with deep sadness and anguish at their current situation. "We're not happy in the plaza," she says. "The children get sick and ask every day, 'When are we going back to Ka'a Poty?' And I have no answer, and these last few days I've been crying from helplessness."

The community was settled on land belonging to both the Paraguayan Indigenous Institute (INDI) and its own property. The INDI itself acknowledges that 1,364 hectares were acquired in 1996 and registered in the Public Registry in 2008. These lands should be allocated to beneficiaries of the Agrarian Reform, in this specific case, to indigenous communities.

“They destroyed the jeroky aty (temple) where we pray and dance; when a child gets sick, we take them there to be healed, and now it no longer exists. They didn't respect our school, which is recognized by the Ministry of Education; they burned it down. Our children have missed classes since June,” Marta continues.

Judicial protections without respect

After the second eviction, they decided to travel to Asunción to demand the return of their land. They set up camp in the Plaza de Armas, in front of the Parliament building. After several weeks, on July 30, they obtained a precautionary measure, an Interlocutory Order No. 258, issued by Magalí Zavala, magistrate of the Twenty-Fourth Civil and Commercial Court of First Instance of the Capital of Paraguay.

But this measure was once again ignored, and the police, without an eviction order, took action against the Indigenous community on November 4. The exodus to Asunción to demand the return of their lands began anew. The community is currently in the process of filing its complaint with the United Nations and the Human Rights Directorate of the Supreme Court of Justice.

“We requested a protective order for restitution so we can return to our community. For two months, they harassed us, and with a new, false eviction order, they defied Judge Magali Zavala's court order and came back to burn our houses and force us to abandon our homes on the Caaguazu side. As a mother and community leader, I am heartbroken by what is happening to us. I have to keep you updated on our case, and we are waiting again for restitution, hoping that Judge Magali will once again grant us permission to return to our community because we are living in unsafe conditions in the plaza where we are currently confined. I ask the justice system and authorities to support us so we can return,” explains Marta.

The Paraguayan state has chosen to prioritize the right to property over basic human rights such as housing, food, and the protection of rural and indigenous children. These are just two examples of violent evictions.

According to the Paraguayan Human Rights Coordinator, 12 cases of evictions against Indigenous communities have been recorded in recent months. At least 10 of these evictions were violent, and 10 cases involved evictions against peasant communities. All the operations share the same characteristics: destruction and burning of homes, food production, and sacred chapels or temples, as well as the theft of belongings and/or small livestock. https://madeinparaguay.net/noticia/desalojos-hay-mucho-que-recuperar-y-poco-que-perder-294

The State ceded the land to businessmen, judges, and prosecutors

To date, Paraguay's land distribution is one of the most egregious in the region in terms of inequality, with 85% of the land in the hands of just 2%. A key element in understanding what happened to the lands that should have been allocated for agrarian reform is the report of the Truth and Justice Commission. This body was created in October 2003 to investigate human rights violations committed by state and paramilitary agents during the 35-year dictatorship of Alfredo Stroessner.

According to the report of the Truth and Justice Commission , 8 million hectares of land were supposed to be allocated to beneficiaries of the Agrarian Reform but ultimately remained in the hands of landowners and cronies, and it is these lands that peasant communities are demanding to this day through occupation.

According to data from the Land Resources Information System (SIRT), since 1936, INDERT (National Institute for Rural and Land Development), the entity responsible for safeguarding the rights of those eligible for Agrarian Reform, had distributed 3.5 million hectares in the Eastern Region. It is estimated that 1,045,000 hectares (35% to 40%) ended up in the hands of people who are not eligible for Agrarian Reform, including prosecutors, judges, supermarket owners, and officials of binational entities, among others.

Another essential contribution to understanding the VIP invaders can be found in the search engine developed by the Paraguayan media outlet El Surti, where they recount how 3,336 families close to Stroessner took over lands that do not belong to them .

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.