The first shelter for trans people in Mexico was activated during the pandemic

The Casa Hogar Paola Buenrostro shelter was founded by trans activist Kenya Cuevas and has been operating since April 2020.

Share

On the last day of March 2020, a state of health emergency was declared in Mexico due to Covid-19. On April 2, Kenya Cuevas, a trans woman and human rights defender , opened the doors of Casa Hogar Paola Buenrostro , the first shelter for trans people in the country, located in Cuautepec, a working-class neighborhood in the northern part of the sprawling suburbs of Mexico City.

At number 59 on the steep Lázaro Cardenas street is one of the realized dreams of activist Kenya Cuevas, a woman known for her strength and determination to build livable futures for people in vulnerable situations.

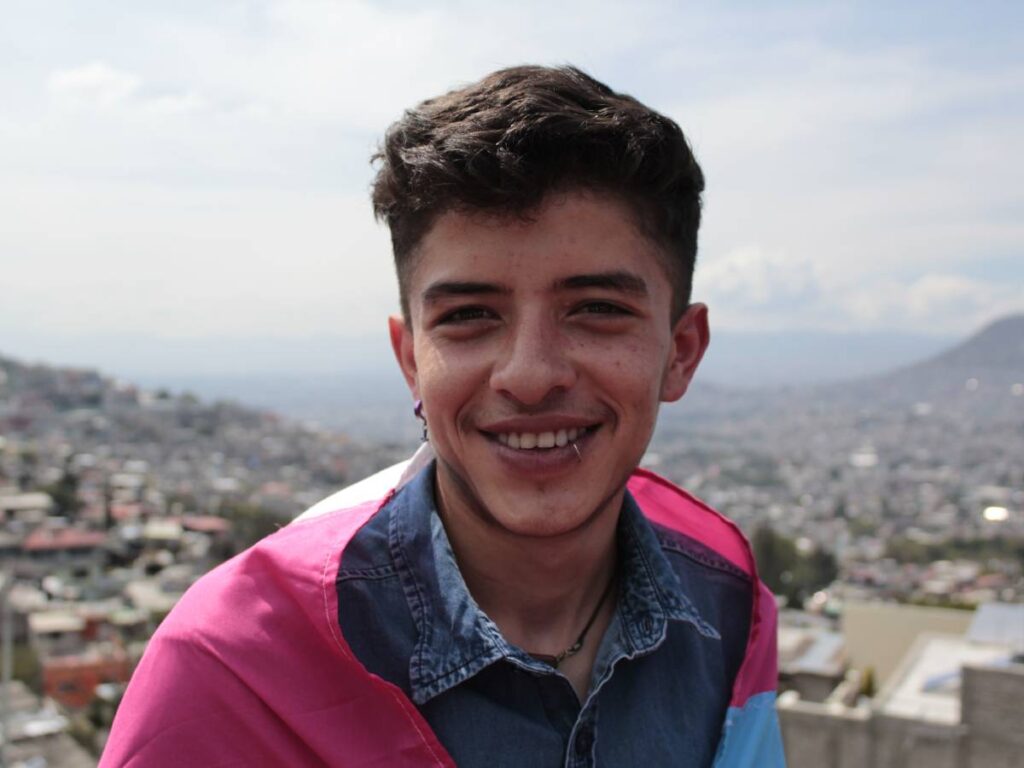

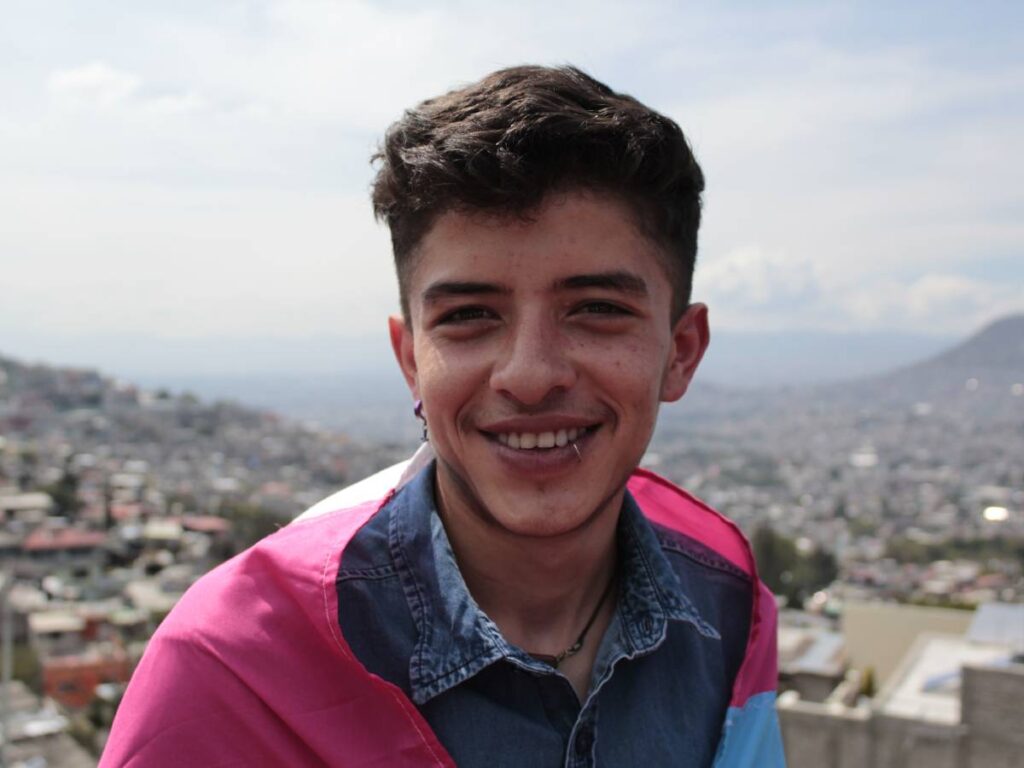

“In March I lost my job, I couldn’t pay rent, let alone food. I needed help. I called Kenya to ask if I could stay at Casa Hogar , and she said, ‘Of course, come on over, my boy.’ I arrived on April 3rd. Today I’m a counseling coordinator. I went from being a beneficiary to being part of the team, and considering these women and trans people my family, and damn, I feel happy,” Christopher says with a big smile.

Christopher just turned 21 and has been living in Mexico for five years. Chris, as he introduces himself during the interview, is a trans man who migrated from Honduras due to the violence his mother inflicted upon him and threats from a man who is still searching for him. Just this year, the Mexican government granted him refugee status.

“Here I can be myself, in my country I can’t.”

Chris received no sex education at home or at school. “I didn’t know how to name my identity, but I felt it, and I felt good when I dressed like a boy,” he recalls. When that happened, his mother would lash out at him, saying, “You look like a tomboy.” Furthermore, his mother’s partners sexually abused him. “All of that triggered my decision to leave home, and I told myself: I’m not going back to that shit.” Chris was 14 years old when he decided to leave home.

After running away from her family, an older man offered her work and lodging but also subjected her to violence. Chris doesn't elaborate much and simply states, "To this day, that man is still looking for me, he has threatened me. In short, my life in Honduras, as awful as it sounds, was a mess .

Like Chris, many LGBTI+ people in Central America are forced to leave their country of origin due to the various forms of violence, discrimination, and hostility they face.

According to the report " I Live Every Day in Fear" published in 2020 by Human Rights Watch, the reasons for human mobility in the Northern Triangle countries (Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras) are due to a multitude of factors such as structural conditions of inequality, systematic violence, human rights violations, violence by security forces and gangs; and in particular, LGBT people also flee due to discrimination and violence based on prejudice towards their sexual orientation, gender expression, and gender identity .

Chris decided to migrate north on February 26, 2017. On foot and by hitchhiking, he traveled from his hometown of San Marcos, in the department of Ocotepeque, until he crossed Guatemala. Along the way, in addition to exhaustion and hunger, he faced sexual harassment.

On March 3, Chris arrived in Tenosique, Tabasco, a state in southeastern Mexico, and stayed at La 72 shelter , one of the few shelters in Mexico with a comprehensive space for LGBT+ migrants . He stayed there for eleven months, met other LGBT+ people, was inspired by the work of the volunteers, and was able to reflect on and put into words what he has always been: “I am Chris, I am a trans guy, I am this bastard.”

“I didn’t find peace until I arrived in Mexico, you know? Because I literally can’t go back to my country. Here I can be myself, but not in my country . First, because of the danger from the person who’s still looking for me, and second, because people like me get killed. It’s like that; going back to our country is like death for us. There’s so much violence against us trans people,” she says.

He's not lying. Since 2016, the organization Trans Europe has ranked Honduras as the country with the most registered homicides against trans people per million inhabitants and clarifies that "when examining the relative numbers, the situation in Honduras is even worse than in Brazil, which has the highest absolute number of reported homicides."

Furthermore, the report indicates a “worrying trend” regarding intersections and emphasizes that “the majority of victims are Black and women of color trans women, migrants, and sex workers .” Likewise, Latin America remains the deadliest region in the world for trans people. Seventy percent of the 375 murders of trans people recorded in the last year occurred in Mexico, Central America, and South America.

“Third time’s the charm”

Chris processed his refugee application at the Tenosique office of the Mexican Commission for Refugee Assistance (COMAR) but it was denied twice.

“The second time I was denied asylum, I decided to move forward, with or without papers, but my goal, however childish, was to reach Mexico City to see the Angel of Independence,” he says. Chris then traveled by bus to the nation’s capital where, with the help of friends, he was able to find a job and rent a place.

At the COMAR offices in Mexico City, Chris told his story for the third time. He says that this interview “didn’t hurt as much,” and after four years of seeking asylum, he finally received a decision . “The third time was the charm, and they just granted me asylum. I can’t believe it because it means I’ll be able to study at a university, have access to healthcare, work, and so on, because basically the Mexican government is now obligated to guarantee those rights.”

Chris is happy, but he would like his refugee card to reflect his name. , transgender people are still not guaranteed the right to identity ; there are no laws that allow for administrative procedures to change their name and gender marker on their official documents.

Furthermore, the Mexican State does not issue immigration documents with the chosen name of transgender migrants. According to Article 8 of the Law on Refugees, Complementary Protection, and Political Asylum , Mexican authorities are violating the principle of non-discrimination, which aims to ensure that “applicants, refugees, and those receiving complementary protection are not subject to discrimination based on ethnic or national origin, gender, age, disability, social or economic status, health conditions, pregnancy, religion, opinions, sexual orientation, marital status, or any other factor that has the effect of preventing or nullifying the recognition or exercise of their rights.”

“Because of the pandemic, it was urgent that I had to open the shelter.”

In February 2020, Chris lost his job, which made it difficult to pay his rent and buy food. “I needed urgent help, but I also wanted to contribute to the shelter. I spoke with Kenya, and she opened a space for me at Casa Hogar,” he says.

Casa Hogar Paola Buenrostro is a dream that Kenya Cuevas had since her activism intensified, when she took to the streets of the city to demand justice for the transfemicide of Paola , her friend. And in whose memory this shelter was named.

And it was in December 2019 when the Secretariat of Inclusion and Social Welfare (Sibiso) gave Kenya an empty property in the Cuautepec neighborhood .

“ I wanted to open it in January 2021, but because of the pandemic, it was urgent that I open the shelter. Many people were affected. There was a lot of hunger, there were no jobs ,” he recalls.

On the night of April 1, 2020, the Mexico City government decreed the closure of hotels, resulting in people who engage in sex work, especially women, being left without housing and without a place to work.

According to a survey by the Council to Prevent and Eliminate Discrimination in Mexico City ( Copred ) before the pandemic, 42.9% of people who do sex work are trans women and 49.6% are cis women.

The research project "Observatory: Gender and COVID-19," promoted by GIRE (a feminist organization for reproductive rights), detailed that at the beginning of the pandemic, the Mexico City government committed to delivering food baskets to sex workers three times, but only delivered them once. They also agreed to provide financial support for three months through debit cards with a balance equivalent to 2,600 pesos per month, but those who received these cards only received a single payment of 1,000 pesos.

From April 2020 to the present, the shelter has provided housing, food, a place to sleep, and comprehensive care, including school support, emotional and addiction counseling, and vocational workshops, to at least 180 people. The majority are transgender women, but the shelter also serves anyone in need.

Most of the trans women who have passed through this shelter have migrated , either from another country such as Honduras, Nicaragua, Cuba, Colombia or Venezuela; as well as from other states of the Mexican territory such as Tamaulipas; Baja California, Morelos and the State of Mexico.

“Here, we don’t exclude anyone. While it was created as a space for trans people, we’ve also provided support, shelter, and guidance to cisgender women and men. We’ve helped people who have just been released from prison, people experiencing homelessness, drug users seeking reintegration, and we’ve served as a safe haven for migrants who decide whether to continue their journey or stay. And we care for all of them with a holistic approach and with love,” Kenya explains.

At the same time the shelter began operating, Kenya Cuevas and the team at Casa de las Muñecas Tiresias , the organization she leads, also started distributing hot meals in Revolución, a sex work hotspot in Mexico City. For five months they served a total of 8,500 meals, and the street became a joyful space where trans women offered musical performances to “ease the uncertainty.”

“The shows were an escape, but they also served to make visible that trans people don’t just put on shows at night in gay clubs, but that we also exist and can be in public spaces… during the day,” Cuevas says.

“The government has a historical debt to us.”

Throughout the years and since she founded her organization, Kenya has not stopped defending the human rights of trans women in this country and of migrants , those who have died for some reason and those who were murdered.

“This hasn’t been easy; it’s also come from suffering, from losses, from murders, from people dying with impunity and structural neglect. It’s been a beautiful experience, yes, but this is a task that governments should be undertaking. The government of this country has a historical debt to all of us , to those of us who were denied the tools and human rights from the moment we said, ‘I’m trans,’” she emphasizes.

Despite the absence of the State, Kenya has not stopped dreaming and today her organization operates beyond the volcanoes that surround Mexico City, in four states: Nayarit, Morelos, Veracruz and State of Mexico where the focus is on life projects, reparation and social reintegration of trans women and men who need it.

The comprehensive methodology consists of four stages: providing documentation, medical evaluations of mental and physical health; school admission, school certification and economic autonomy workshops; professionalization and “independent living” , when the people who go through the shelter are able to maintain a job and rent a space.

“Without formal education or anything, but with life experience because I also experience these vulnerabilities and understand them, I'm always one step ahead. So much so that at Casa de las Muñecas we managed to create a comprehensive methodology and intervention. And I'm not just bragging, but I have many positive results and many women who have come through here who are now at peace, know their rights, have a job, rent a place, and are motivated. Seeing these women happy is the best reward ,” Cuevas confesses.

“Our greatest revenge is that we are happy”

Chris was inspired by the volunteers at the La 72 shelter. From then on, the desire to "give back" what they had given him never left his mind. At the children's home, that feeling grew even stronger when he witnessed firsthand the strength and love of Kenya Cuevas, whom he feels is like a loving mother, "the one who never hugged me, whom I never hugged, the one who never told me 'I love you,' and to whom I never said 'I love you,'" he says.

“…but here I feel happy, I’m myself and I’m with family . I went from beneficiary to counseling coordinator, a position I don’t know how to define, but damn, I feel happy because Kenya and the rest of the team trust me, they gave me responsibilities. Thanks to them I achieved this, but also thanks to myself because I’ve worked harder than you can imagine, and now it’s very difficult to convince myself of that,” Chris concludes.

Kenya's dreams never run out, nor does her strength. Before I leave, I ask her, "Where do you get so much strength?" She smiles, laughs, and takes a deep breath.

“Oh, darling. I don’t know. The truth is, I think it’s because of such a thirst for justice amidst so much impunity. And because I also have many personal dreams, and that involves seeing a more inclusive, more empathetic, more community-oriented society, and I continue working to build it. My work doesn’t end after a public apology for Paola’s trans femicide ; on the contrary, it’s the beginning of the fight because otherwise, we won’t be happy. And I will continue working until the last day of my life because our greatest revenge is for us to be happy.”

Two years into the COVID-19 pandemic, the Mexican State has not taken action to lessen the impact of the health emergency specifically on LGBTI+ people, sex workers, and migrants because there is no official data that allows us to know how it has affected these populations.

On the contrary, it is activism like Kenya's and its way of building community that has allowed Chris and so many other trans people to find, in addition to food, shelter and education , a loving space to be free at Casa Hogar Paola Buenrostro.

We are present

We are committed to journalism that delves into the territories and conducts thorough investigations, combined with new technologies and narrative formats. We want the protagonists, their stories, and their struggles to be present.

SUPPORT US

FOLLOW US

Related notes

We are present

This and other stories are not usually on the media agenda. Together we can bring them to light.